Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Game writer and longtime GDC speaker Evan Skolnick shares an excerpt from his new book, Video Game Storytelling: What Every Developer Needs to Know About Narrative Techniques.

A simple truth stands at the core of both my long-running GDC game narrative tutorial and my new book. And it's a truth I’m determined to shout from the rooftops: nearly all game developers are storytellers, whether they realize it or not. They’re ultimately the people who do the work of bringing a game’s story to life.

You can have the best of narrative intentions on your game project, and hire the most talented game writer around — but if the rest of the team isn’t aligned with the goal of telling a great game story, or if they’re on board but untrained in storytelling, your final narrative result will still probably end up being mediocre, if not worse.

So, with my tutorial and now with this book, I’m trying to reach developers who aren’t writers but who are nevertheless part of the storytelling effort. I want to provide them with a common language of story that can smooth the way to fruitful narrative collaboration throughout the development process. Designers, artists, animators, audio experts, engineers, producers, QA testers — all have their part to play in the story development effort.

My goal: show all developers how core storytelling principles can be applied to their own craft.

When I was first approached by Random House to write a book version of my six-hour tutorial, I imagined the creation of such a manuscript to largely involve taking my hundreds of slides and converting them to book format. It sounded pretty simple! But of course it ended up being much more involved than that.

I learned a lot during the long process of adapting the workshop to print and fleshing it out where necessary. And these are the learnings I’m now plowing back into this year’s version of “Better Storytelling in a Day”, which I’ll be presenting at GDC on Tuesday, March 3rd.

The book is divided into two main sections.

Part I, called “Basic Training”, provides a grounding in well-established principles of Western storytelling: the common language that everyone on the team can use when discussing narrative elements. This is essentially a text version of the tutorial.

Part II, “In the Trenches”, represents a deeper dive, investigating the specifics of storytelling as they relate to the main areas of game development, and describing in greater detail how members of each discipline can contribute to — or potentially sabotage — good storytelling. Topics in this section include team leadership, overall game design, mission development, environments, audio and others.

In Part I's Chapter 4, “Characters and Arcs”, we cover the two most important characters in nearly all stories — the Hero and Villain — and then move onto the topic of Character Arcs, which is excerpted below. I hope you find it interesting. And if you happen to see me at GDC next month, please don't hesitate to say hello!

Heroes aren’t the only characters who confront conflicts over the course of a story; nor are they the only ones who change and grow. The confrontation of a conflict and the potential resulting change in a character and/or his situation is called an arc.

The most obvious and dramatic character arc in any story almost always belongs to the Hero. As already covered, the Hero’s change and growth — his arc — is a defining characteristic.

The story’s plot and the Hero’s arc are rarely the exact same thing, but are almost always inextricably entwined. Going back to the classic example of Star Wars and its Hero Luke Skywalker:

Plot

A repressive galactic empire is kidnaping princesses, destroying planets, and seeking to crush the freedom-loving rebels who oppose it.

A Force-sensitive farmboy and his allies fight to rescue the princess, escape with crucial military plans and attempt to deal a major blow to the Empire by destroying their fearsome new weapon.

The Death Star is destroyed and the rebellion lives to fight another day.

Hero’s Arc

Young Luke Skywalker, a farmboy who dreams of being a heroic space pilot, feels trapped by circumstances on a dusty planet at the edge of the galaxy.

Luke is swept up in an adventure that forces him to interact with colorful and dangerous characters, learn about the Force, and take enormous risks to help others.

Luke destroys the Death Star, and is now clearly no longer a boy but a man.

Note that both plot and arc are structured with a beginning, middle and end — setup, confrontation and resolution — just like the Three-Act Structure.

Arcs apply to all major characters in a story. The most compelling ones chronicle a deep change in a character’s values, in what they stand for and who they are. These can be called growth arcs. This is the kind of arc we expect to see in a Hero, for example.

But even if a major character doesn’t change or grow as a person over the course of the tale, it’s likely their situation does. We can refer to these as circumstantial arcs.

Each arc includes a beginning point (who is this character and what is her situation when we first meet her?), a middle (what happens along the way?) and an end (where does this character and/or her situation end up?). Let’s look at two more character arcs from Star Wars.

Obi-Wan Kenobi’s Arc

Obi-Wan is a powerful Jedi in hiding, considered by the local population to be a crazy old hermit.

After seeing Leia’s call for help, he decides to leave his exile and begin training Luke in the ways of the Force. He ultimately sacrifices his life to allow the others to escape.

From beyond the grave, Obi-Wan guides Luke and helps him destroy the Death Star.

Han Solo’s Arc

Han Solo is a self-assured, self-centered smuggler who relies on and believes in just one thing: himself.

Han sees Luke, Ben, Leia and others taking huge risks and making sacrifices for each other and for the greater good.

Han chooses to help his new friends rather than see to his own interests, demonstrating that he has grown from a simple scoundrel to a heroic figure in his own right.

As you may have noticed, these two arcs are of different types. Obi-Wan experiences a change of circumstances: he goes from seemingly inconsequential hermit to ghostly facilitator of the Death Star destruction. But his core attitudes have not really changed — just his situation.

Han Solo’s journey, on the other hand, represents a true evolution in his character — he’s not the same person he was when we first met him. He’s grown. He’s learned to care about something other than himself.

Obi-Wan’s transition is a circumstantial arc, while Han’s is an example of the more deep and resonant type: a growth arc. Both, however, are character arcs, and both make Star Wars a richer story experience.

Every major character who appears in a story-driven game should have some kind of identifiable arc. If you were to extract each prominent character’s individual story out of the overall narrative and examine it, you should find that it:

has a beginning, middle and end

is driven by a conflict, which is in turn driven by a “want/but” situation

is resolved (even if that resolution is negative)

But in games, what kind of characters are we talking about?

Partners/Squadmates/Allies

Your closest allies — whether diving into battle alongside you in gameplay or helping to support and inform you from the sidelines or during interstitial story moments — need to feel like living, breathing people. Give them something extra they care about or want besides your shared goals... then pay it off.

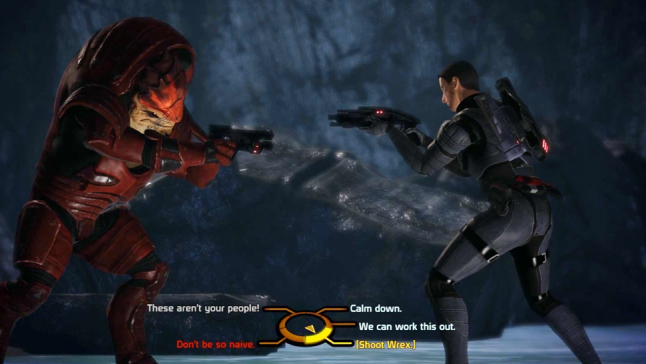

A great, interactive example of this approach can be found in BioWare’s Mass Effect. The hulking krogan bounty hunter Wrex, who fights at your side for a good deal of the game, comes from a warrior race ravaged by a bioweapon that causes stillbirth in all but .1% of its infants. When he learns that the story’s Villain, Saren, is trying to cure this genophage in order to create an army of krogan soldiers, Wrex draws his weapon, defiantly telling player character Shepherd that they must not destroy Saren’s facility, lest the cure be destroyed as well.

Depending on player choice, Wrex’s arc — indeed, his very life — may end right here, as the player or another supporting character kills Wrex on the spot. Or, if the player finds a way to avoid the gruff krogan’s death, Wrex may go on to become an important figure on his homeworld in Mass Effect 2 and, eventually, the de facto leader of his entire race in Mass Effect 3. This represents an interactive character arc with plenty of punch to it!

Mentors

Although a stereotypical Mentor character might not have good odds of surviving all the way through your story, giving him a strong arc can make him more impactful and memorable. Often, a Mentor’s goal is to indirectly resolve the conflict by encouraging, advising, training, and/or equipping the Hero.

The Mentor character of Conrad Roth in the 2013 remake of Tomb Raider is a prime example. (Spoiler Alert: if you haven’t played this game but intend to, you might want to skip to the next heading, “Named Enemies”.)

Beyond the goal of helping the shipwrecked group escape from the island — an objective he shares with playable Lara Croft — Roth, as Lara's surrogate father, has his own personal goal of encouraging and preparing her for the trials that he knows await her.

In his final scene, Roth uses CPR to resuscitate Lara from a near-death state and defends her from incoming enemies with his pistol, eventually shielding her from an incoming axe with his own body. But even this isn’t enough for Roth, unwavering in his determination to protect and mentor Lara. In his dying moments, with his very last breath, he continues to encourage and empower his protégé:

“You can do this, Lara. You’re a Croft.”

While his life ends at this point, it could be argued that his arc continues, as through the rest of the game Lara strives to live up to Roth’s belief in her.

Named Enemies

As discussed earlier in this chapter, a two-dimensional bad guy who only seems to exist to throw obstacles in the path of the Hero makes for a flat Villain and a less-than-compelling story experience. This axiom also holds true for other enemies (or Henchmen).

Now, this doesn’t mean that every single one of the countless hordes of cannon fodder the player might encounter over the course of a twelve-plus hour game must have his own detailed back story and character arc! However, the more prominent ones — such as mini-bosses, bosses, and probably any enemy with a name — most certainly should.

The character histories don’t all need to be elaborate, and you can compress them to a fairly compact timeframe if necessary. The original BioShock does this in a very effective and streamlined way. As you approach the area in which you’ll eventually confront a mini-boss, you begin to find audio recordings that paint a picture of the character — history, personality, desires, goals, etc. The environment often offers more clues — writings, photos, illustrations, graffiti, horrific crime scenes — perhaps contrasting the present state vs. the past recordings you’re listening to. Finally, by the time you directly encounter the mini-boss, you have a good notion of who he is, what he wants, and why you’re about to try to kill each other.

Quest-Givers

Any NPC who asks the player to complete a task can be considered a quest-giver. By definition, these characters will have some sort of arc because a) they want or need something, and b) they require the player’s help to get that something, and c) the player will either resolve their conflict or not.

Whether it’s an herb-seeking alchemist in World of Warcraft, a tribal warrior goddess in Far Cry 3, a repeatedly-kidnaped journalist in Red Dead Redemption, or an elderly, violin-playing woman in Fallout 3, quest-givers can inject colorful doses of character and drama to gameplay objectives that would otherwise boil down to, “Go here, kill this being and/or collect this object, return.”

Completing each quest-giver’s arc is key to providing some satisfaction to the player, since she’s the one who performed the actions necessary to resolve the NPC’s conflict.

When it comes to your main and secondary characters — again, this generally means anyone you’ve cared enough about to actually name — ask yourself, do they all have character arcs? And do they all resolve and pay off?

If not, you’ve got some work to do... and I don’t mean getting rid of their names!

Excerpt copyright © 2014 by Evan Skolnick. All rights reserved.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like