Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Composer Austin Wintory has repeatedly won acclaim for his soaring video game scores, but it was his roots as a musical theater nerd that fueled his work on Stray Gods.

Composer Austin Wintory has a secret that might surprise you. For years, his work in games like Journey, Assassin's Creed Syndicate, and Aliens Fireteam Elite has consisted of sweeping scores populated with orchestral swings and emotive choirs. You'd be forgiven for thinking his musical passions were strictly inspired by cinematic soundtracks or the symphony.

You'd be wrong. Wintory's secret is this: he is a giant musical theater nerd.

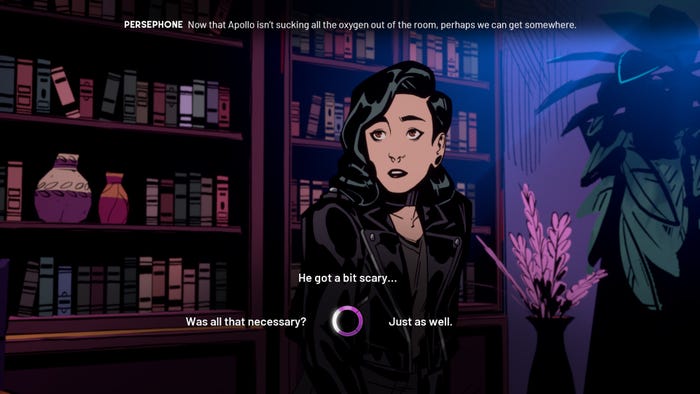

If you're familiar with the premise of Summerfall Studios' Stray Gods, that may not surprise you. It's a unique experiment of a role-playing game—it's a choice-driven murder mystery that's also a full-length musical. And even though it's about the Classic Greek pantheon, there's more of Sondheim, Fosse, and Lloyd Weber in this game than Hades, or God of War.

To hear Wintory tell it, a game like Stray Gods is something he's been waiting for a long time. Buried in his past are a number of musical projects. He and some friends once staged an unauthorized musical inspired by Buffy the Vampire spinoff Angel, and a decade ago Australian musical trio Tripod (who joined him to work on Stray Gods) staged an evening-length musical with Wintory's deep collaboration.

So when he teamed up with Summerfall to make music for Stray Gods, he knew he'd be able to bring one of his great passions to the world of video games. But he also knew it would be a daunting project—any video game score demands close collaboration with developers, and making a musical would practically mean he was stepping into the roles of level designer, narrative designer and more while doing the work of composer.

That's no easy feat. But Wintory was glad to share some of what he learned by taking on those additional tasks—lessons that might help you if you say, decide to make a riff on Vampire Survivors with Busby Berkeley musical numbers.

Wintory explained that making Stray Gods (which changes musical styles as players make different narrative choices) introduced two unique production challenges. First, each of the different musical paths had to be distinct and avoid referencing events (or melodies) encountered on the other paths.

But second, each of those paths had to be consistent, to sell that uniqueness. They're each defined by a different color, personality trait, and musical style. The "red" options are more "kickass," choices labeled in green are "compassionate and empathetic," and choices in blue would be "clever."

"Red drags things in a hip-hop direction," Wintory explained. "It's not that it turns into a hip hop song, it's that suddenly [the song] gets chattier and there's more density to the lyrics. It's the same way the best hip hop is like this tsunami of poetry.'"

In that section, Wintory would lean on an amplified and distorted electric bass as part of the orchestration—even in more "sad, delicate" songs. He likened it designing for "basic expectations" that players have of games. If they're playing a shooter and click the left mouse button, the gun needs to fire every time. If they make consistent choices in the musical dialogue trees, they need the music to reinforce the tone of those choices across multiple songs.

Self-discipline makes it easier to produce consistency of course. Wintory noted that on this project, he did much more production work he normally subcontracts out to a mixing crew (he compared this part of his role to being more of a 'pop music producer'). "This was just so fractal and branching...it would have been so much more difficult to bring someone in to understand all that."

But no composer can sit alone in a room when making a musical. Along with the aforementioned collaboration with Tripod, Wintory obviously needed to bounce back and forth with the team at Summerfall who were designing the story and implementing the musical choices. And maybe more importantly, he had to ensure the game's performers could understand what he was going for with the different twists and turns the music took.

Here, Wintory gave a lot of credit to actor Troy Baker, who did double duty as a cast member and voiceover director on Stray Gods. "I learned so much from sitting in that booth from Troy," he recalled. "His insights were so consistently unexpected and he always knew how to say 'the least amount.'"

What does "the least amount" mean? Wintory said he was referring to how Baker could efficiently communicate notes and feedback to the rest of the cast. The composer lamented his own tendency to explain his ideas at length (this comment came seven minutes into a response to a single question), and said he admired how Baker could "engage the imagination of another artist."

"The goal...is not to position them like a reticulating doll," he observed. "You're trying to spark [inspiration] with somebody, and then they run with it. Baker had a real knack at figuring out what is a one-sentence way to light that fire within somebody."

If you need an example, consider something out of the "method acting" technique. Though the process has been publicized by ardent practitioners like Daniel Day-Lewis, there are more everyday uses to the technique. If there's a line you need delivered with a low, simmering anger, you could obviously tell the actor that you need it delivered with "low, simmering anger."

You might get a good result. You could also try asking them to deliver it with a note like this: "give me a take where you're angry but trying not to let anyone know you're angry." It invites them to interpret such a note—sometimes with their own experiences with such emotions.

Wintory seemed in awe of what actors like Ashley Johnson and Anjali Bhimani did with those notes. He particularly sang the praises of Bhimani's interpretation of the mythological monster Medusa. "It was a completely different version of what we were imagining. All of us instantly were sold. There was no skepticism, but none of us saw it coming, which was so wonderful!"

He said he wants to bring that type of feedback to the rest of his composing career. And really, these are the kinds of tips that could benefit many aspects of game development. If you're struggling with something else in the process—be it writing, design, or art—try thinking of how quick notes that inspire your collaborators could go further than point-by-point feedback.

In other words, you, like Wintory, can learn new ways to trust your fellow developer—and take delight in the unexpected results that pop out.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like