Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

During summer of 2014, foundry10 had 4 high school age interns pursue their goal of making a video game. With a focus on minimal structure, the program offered insight into how game creation impacts learning and how it can be used as a tool for students.

“We want to make a video game”

This was the first thing we heard when we asked four teenage boys what they wanted to do for a summer internship. Over the next hour, the, then potential, interns outlined their project for us. It was ambitious and very cool, complete with an entire storyline spanning multiple levels. We said “go for it”, and over the next few weeks they chose Unreal 4 as their engine, set about preparing with tutorials, and we set up a meeting for them with their mentor-to-be Jared Gerritzen, VP of Developer Relations at MLG. During summer 2014, we were able to see what happened when a group in our intern program decided to try to make a video game in eight weeks.

The question for us became what is that value and what really happens when teens make games?

When we at foundry10 asked over 100 games industry professionals if there was value in teaching game creation to high schoolers, the answer was overwhelmingly “Yes!” The next part of the question was what that value was, and the answers we received were dizzyingly diverse. It seems most people agree that there is value in teaching game creation.

Our student-led internship program is structured for one interested student to assemble a team and pitch an idea for a project, of any topic, they are all intrigued by. If the idea sounds like something we can help with, we support them with any resources they need to make it a reality, including connecting them with an industry expert mentor to guide and help the interns get off the ground.

Foundry10’s goal with this program is to see what happens when teens are given access to professional-level resources and guidance to carry out their own idea, whatever that may be. We often feel people underestimate what teens are capable of, and we want to see just what a highly motivated group can create when given the chance. Instead of putting the interns in a highly structured environment, we wanted to use minimal structure, leaving the onus of responsibility on them. The mentors were there as supportive advisors, but the teens called the shots and worked off of their sole vision.

Now we have the chance to share the experience and what they took away, as well as what we found about game creation as a learning tool.

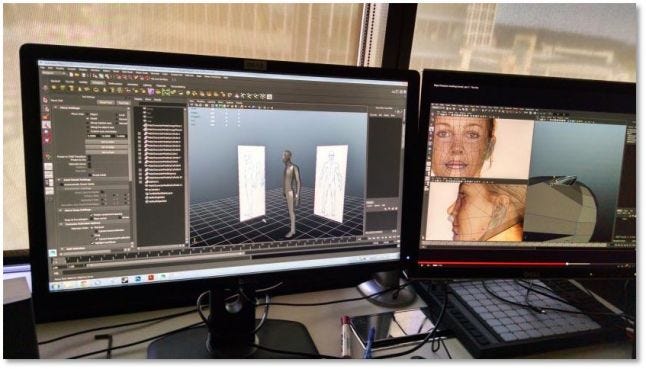

“We’re all trying to find what we are best at; you have to model first, then texture, then integrate and then code; you’ve got to work in steps”

We heard this during the mid-point interview from one of the interns. With only one of them having some experience in a 3-D modeling program, each team member had to decide what part of the game they would tackle. Each had ideas at the start of where they were going to fit in, but once they got into it there was some chaos with roles. Everyone wanted to be doing everything, but specialization was needed.

Over time and due to the necessity of manpower, each intern got their hands dirty in every facet of the work. Ultimately it was this exposure drove the interns to narrow their interest areas. After an awesome day in the Valve sound studio, for example, the intern who was doing 3-D modeling and art decided to switch to the sound production. In a similar experience, the story writer/creative lead wound up interested in the technical aspects of map-building, finally spending four days trying to isolate a single error in the lighting. This confirmed our idea that given the least amount of structure and maximum amount of professional level exposure, the interns would self-organize into their specific interest areas.

Just as interesting as the technical role discoveries were the social roles that the interns fell into. When the pressure began to ratchet up as deadlines approached, the demeanor of the interns changed. We were really surprised by some of the interns’ reactions to the pressure. For example, the quiet and shy intern with a passion for games moved into a leadership and directional role, and the outgoing ‘joker’ of the group buckled down and went deep into technical work. The program’s minimal structure allowed for these kinds of shifts and changes to be happen naturally as each member of the team found their place.

“You need to be able to adapt to an issue along the road without flipping out”

With deadlines coming up, it was easy to get frustrated. The mentors were available as scheduled, yet there were still moments when the interns would find themselves at a difficult impasse, without the necessary knowledge to progress. They knew they had to find some way around the problem and could not afford to lose time due to anger and disagreements.

Adapting to complex situations is something almost entirely learned by experience, and video game creation proved to be a great exercise for this. Even with their decided job roles, the interns frequently were pulled into tasks they were not expecting and/or that required them to think differently. The bugs they encountered ran the gamut from pathing issues to voice acting, but they had to react to each of them or face delays to the project. At the end, each of the interns mentioned the importance of being adaptable and how they had learned about their own style of reacting to problems.

The need for adaptability, in particular, highlighted the power of putting the responsibility of completion on the interns. In a typical class structure, the threat of negative grades is enough to push students into going with tried and true solutions. No grades or assessment mean the interns are free to try out creative approaches to problems, rather than what they know will work. The result was an expanded ability to think outside of the box and increased confidence when facing uncertainty.

“At the midpoint interview, I thought I knew how much went into making a game, now I know I had no idea at that point.”

Exit interview questions that asked the interns to reflect on the experience were very interesting. When the interns chose Unreal 4 as the engine for their game, one of the biggest suggestions that we got from the developers we spoke with was that it is important to manage expectations. Coming in, the interns wanted to get as far as a beta. We told them what the developers had told us: “it would be realistic to get one room of one level.” This concept of setting expectations was something that we originally thought would be a big deal. Now at the end, it seems like less of a concern. The interns were going to have big ambitions regardless of what we told them, trying to set realistic goals is tough when the word ‘realistic’ has different meanings for everyone involved.

The data we gathered revealed that internalizing expectation management is very difficult for a teen to do. The best way to learn is to try to reach the height of your ambition, and fail.

Video game creation is an excellent tool for this because failure is not just allowed, it is expected. In our internship program the goal was never to make a successful game (that is up to the interns themselves), but rather to see what they learn. Compromises need to be made, there will be crunch times, and ideas will sometimes need to be changed or even dropped. When it came to the end though, the loose structure that put so much in their hands was very well received. They enjoyed getting to figure things out for themselves, and felt the freeform structure was important for the experience overall.

“I’m not sure I want to make video games, but it was the broader skills that give the value.”

Two of the four interns ultimately decided that working on video games might not be for them. Constant bug fixing, looming deadlines, and the challenges of creative compromise are just not for everyone. What was interesting about hearing this from them, though, was the fact that they said they were happy to have had the experience. It was the structure that gave value to the program for them, the idea that they were responsible for their own decisions and the associated consequences.

The concept of ownership, and the drive to learn that it creates, is a core value to the program, regardless of the subject matter.

Furthermore, there is immense value in coming to realize that a particular career path is not a good fit. Aside from the obvious benefits like saving time in college, the interns questioned why it was they had come to the conclusion that game creation might not be their desired field. Questions like that bring students to insights into what interests them and why. Personal reflection and soul searching like that is so important, yet, so difficult to foster in a classroom. However, when the decisions come from the teens organically, they begin to piece together their own unique motivators.

“The fun is having the camaraderie and making something with guys you know and care about.”

Towards the end of the internship they really needed to pull together as a team. All of the interns mentioned that they learned a lot about how to work in a team as a result of this experience. Compromises had to be made, some ideas were lost, but new ones sprouted up. As the program went on, the interns became increasingly skilled at dealing with disagreements, finding solutions, and coming together as a team to implement them. This collaborative element is huge for most workplaces these days, and the interns definitely got a taste of that sort of environment.

It is clear to us at foundry10 that game creation holds incredible value to students, if done right. But what is “right” when each learner is different? The discussions need to happen about how game creation can be customized to the group doing it, and what would be the implications. Foundry10 was started with the goal of understanding learning, and this means understanding individuality as well. Game creation, and video games in general, is/are a deeply personal experiences, with different meanings to each person working on or even just playing them. In our internship program, each intern connected with their own unique combination of the experiences they had, finding meaning themselves rather than having it fed to them.

We are currently developing a more formal game creation program with the hopes of digging deeper in the subject of games and learning, and will be running more game creation internships in the future. All of us at foundry10 are passionate about finding what fuels learning and highlighting the under-recognized skills that come from interesting and non-traditional programs. As we continue to examine game creation, we want to provoke some discussion among professionals.

Having the input and collaboration from across the industry is important to crafting great experiences for teens. If you want to be a part of this discussion, or have questions for us, email [email protected] or find us online.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like