Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

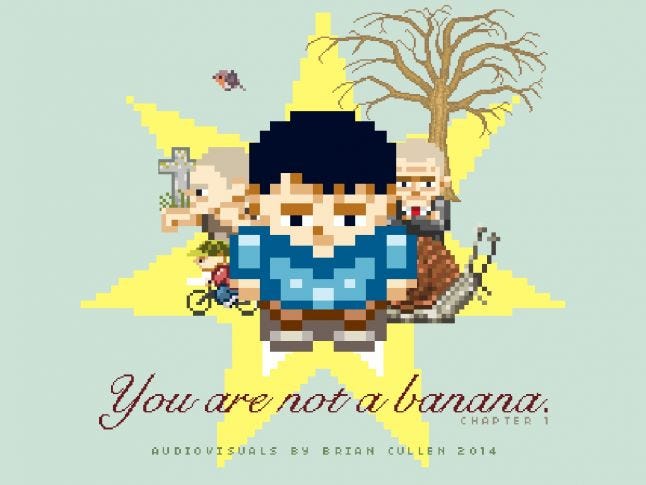

I wrote the following paper after creating an experimental video game in a post-doc position at University of Waterloo Canada. The paper highlighted my creative aims and thought processes when designing You Are Not A Banana.

Note to reader: I wrote the following paper after creating an experimental video game in a post-doc position at University of Waterloo Canada. The paper highlighted my creative aims and thought processes when designing You Are Not A Banana. The paper has not been published previously. I would also like to note that the paper covers a very early student version of the game which contained a pixel art collage of other famous artworks that I believed fell under the category of 'fair use'. Subsequent versions of the game, created before the game was sold on Steam, do not contain the possibly infringing material.

You can pick up the latest version of You Are Not A Banana on Steam here or check out the demo for my latest game Mayhem In Single Valley on IndieDB, GameJolt, or Itch.io.

Brian Cullen

The Games Institute

University of Waterloo

Waterloo, Canada

Abstract—Free software packages such as the Unity game engine enable artists, hobbyists and amateur programmers to develop video games, a medium that was recently the domain of large corporations and specialist programmers. You Are Not A Banana is a retro-style video game that contains personal narratives, alternative themes (such as critiquing the art world) and emphasizes the importance of sound design. This paper illustrates the creative possibilities of working with video games as an artistic medium and provides a walkthrough of the video game in the process.

Keywords—Video Game Art; Game Sound; Sound design; Retro Gaming; Nostalgia; Pixel Art; Sound Art; Unity; FMOD

Funding for the project was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada in the form of a Partnership Grant.

You Are Not A Banana (YNB) is a postdoctoral video game project created in collaboration with The Games Institute and IMMERSe Partnership research initiatives at the University of Waterloo. You Are Not A Banana was created using the Unity video game engine and the FMod Designer audio engine. The project explores the use of subjective narratives and alternative themes in video games using techniques that emphasise the importance of sound design. Martin [1] observes a lack of legitimacy given to the use of the video games medium in the art world. This paper addresses such criticisms and the legitimacy of video games as an artistic medium. The paper covers a number of key compositional concerns relating to video games and art. The main topics covered are: the difficulties of incorporating personal narratives and alternative themes into gameplay, including issues relating to the relationship between author, videogame and player; the use of pixel art, retro sounds and the role of nostalgia in game design; and the benefits of using sound in expanding level design beyond the visual. For documentation purposes, this paper is structured as a walkthrough, however because videogames are multimodal, the topics outlined above are discussed in various combinations alongside key sections of the game.

Mitchell and Clark [2] describe difficulties surrounding the consumption of video game art. They assert that the art world may lack knowledge in relation to video games and that gamers may lack knowledge in relation to art. This paper functions as a walkthrough for those interested in art (but with little experience with video games), whilst providing gamers (with no background in art) with a snapshot of the author's intentions and concerns. Andrews [3] speaks of a similar dual function in relation to Neil Hennessey's Pac Mondrian (2004): "Pac Mondrian is not solely for those interested in visual art but also for anyone who likes Pac-Man."

There is a reoccurring discussion surrounding whether video games can be considered art. However, both inside and outside the art world, no definitive definition of art exists. Therefore, while the terms 'art' and 'artist' may be useful for delineating areas of debate, their meanings are dependent on the subjective understandings and experiences of the person asking the question. The 'is it art?' debate has extended into studies of video games. For instance, the ability of video games to expand human consciousness is often questioned. Devising answers to these questions is complex. Smuts [4] asserts, "if defining video games requires a general definition of games, it may well be one of the hardest problems facing the philosophy of art."

Several authors, artists and game designers tackle these issues head on. Smuts [4] points out, "though one may say that many video games lack artistic value, the same can be said for some products of any artform without calling the value of the whole enterprise into question." He later asserts that "... video games are possibly the first cocreative, mechanically reproduced form of art: they are mass artworks shaped by audience input."

Other authors write about games in a way that aligns with traditional notions of art and experience. Bissell [5] describes playing retro platform games as follows, "... I sometimes feel as though I am making my way through some strange, nonverbal poem". He later describes playing Mass Effect; "to say that any game that allows such surreally intense feelings of attachment and projection is divorced from questions of human identity, choice, perception, and empathy - what is, and always will be, the proper domain of art - is to miss the point not only of such a game but art itself" [5].

Questions of validity extend into the gaming community. For instance, certain experimental games are not recognized as being 'games'. Davey Wreden [6], creator of The Stanley Parable (2013) has reacted with the following; "if I spend any energy justifying my work or the work of any of these people, then to me it’s just validating the question." Other critics battle it out online. Jones [7] writes, "the player cannot claim to impose a personal vision of life on the game, while the creator of the game has ceded that responsibility. No one "owns" the game, so there is no artist, and therefore no work of art." In a rebuttal, Maeda [8] writes, "Because unlike the mechanical function of a car, a narrative replaces the act of physically getting you from point A to point B. A narrative that you, the player, gets to drive and live through until it’s game over. This is where videogames become an art-like act of “personal imagination” (if you agree with Jones’ definition)."

Stockburger [9] suggests that "everything can be art and it is much more interesting to discuss the unique characteristics and the creative potential of computer games than to keep the galleries free from entertainment". Experimental game developers Tale of Tales [10] believe that it is art that will be redefined by video games, "We think modern art has reached a cul-de-sac [...] we are trying to bring the artistic experience to a wider audience". Lowood [11] offers an alternative debate; "Instead we should ask if high-performance play is capable of transforming our notions of how art is created". While the "is it art?" debate may prove useful, it may prove more beneficial to ask if a work is 'meaningful' on a case-by-case basis.

YNB seeks to explore the "is it art?" debate while remaining accessible. You Are Not A Banana aligns with Pippin Barr's [12] notion of curious games and of curious designers, in which the creation process, the finished product and the relationship between the player, the game and the author can be understood in terms of curiosity. This paper contributes to YNB, which can be viewed as an individual creative research project, by examining the artistic potential of using a video game as an artistic medium. It also serves to document the creative concerns of the author at point when video game creation technologies have become more accessible than ever.

Collins [13] points out that the history of video games is repeating itself, and that the "one-man band" game developer has returned. Although development software and publishing has become more accessible, Condon [14] states that the creation of a full game is "...an incredible drain on any interesting conceptual momentum." The author can attest to the validity of such claims. However, as software and user created content evolve, the speed and ease at which individual artists will be able to transcribe their ideas into a playable video game will hopefully improve.

The imagery, sounds and interactive events in YNB were designed in line with traditional fluid and emergent artistic approaches. As I tackled technical problems I discovered technical possibilities. These possibilities led to new content. While researching, I was surprised to learn both the creation of independent and blockbuster games took a similar approach. Garbut [17] states in relation to Grand Theft Auto V, "the world is built first, then missions, then structure and story, and all the time all our systems are developing and changing". Similarly, Wreden [6] states, "It’s all so fluid, right? I mean, there’s nothing ever set in stone and very little of [my design choices] are premeditated (2013)."

These approaches mirror artist practices that begin with broad gestures then refine a work through a transformative feedback loop with a medium. Independent games such as Proteus [15] (described by its creators as "A game of audio-visual exploration and discovery" [16]), Gravity Bone [18] and Thirty Flights of Loving [19], show that games can have a 'stream of consciousness' appearance that runs counteractive to the regimented code that dictates their structure.

In a discussion of the video game Battlestar Galactica (2003) Reading and Harvey [20] observe that "popular culture is redolent with the past". There are numerous online artefacts that lament more 'innocent' times. Consider for example Andrew Barker's [21] rendition of Billy Joel's 'We didn't start the fire', entitled 'We didn't own an Ipad' or movie loglines such as 'a drama centered on a group of people searching for human connections in today's wired world' [22]. It is also not uncommon to view headlines echoing these sentiments ('Family ditches computers, lives like it's 1986' [23]) and there seems to be a general unease with the current rates of technological growth and dependency. Similarly, YNB rejects the state-of-the-art approach and utilizes the aesthetics of the past. This is a quasi-political act against progression without contemplation, although the issue is admittedly more complex.

Many artists today plunder the technologies and aesthetics of the past as a form of creative expression. NullSleep (a.k.a. Keremiah Johnson) plays retro-style techno music, produces photographic works that superimpose old-school sprites onto city landscapes and even hacks 80's games [24]. Luke Jerram [25] created a life-sized pixelated sculpture of his daughter Maya, concentrating on her mobile phone. Taylor and Whalen [26] describe these practices as 'remediation' or a "one-sided projection of something old onto something new". Aside from artists, reports [27][28] of fathers 'modding' games for their daughters, swapping the roles of Mario and the Princess in Donkey Kong or changing the text in Zelda to be female-centric, point to an engagement with the past whilst acknowledging a need to evolve. Johnson's asserts that such blurring of the lines between adult and childhood cultural behaviours is a positive development [29].

Isbister [30] points out, in relation to the SIMs that many big-budget games rarely deal with everyday issues. Condon [14] observes that mass pop games always avoid connections to the real beyond the visual. In an interview with Swalwell [31] game artists Julian Oliver and "Kipper" discuss the lack of political content in relation to MMORPGs . Such trends have left a gap in the spectrum of what games can be, a gap that independent developers and artists are eager to fill. In response to this gap, the 'everyday' occupies a primary place in YNB. In addition, the use of a retro aesthetic for YNB allowed me to reflect upon the sounds, imagery and experiences of my past.

Many video games today emulate the look and sounds of the 8-bit and 16-bit games of the 1980s and 90s. While producing retro games can be cost effective, it more importantly taps into a desire to experience the past. Such desires are seen as a valuable commodity. Collins [32] points out that even as Nintendo games systems advanced to 16-bit processing capabilities they often maintained an 8-bit aesthetic.

There are other interesting formal attributes to pixel art and simple synthesised sounds. Fenty [33] asserts that although retro images require effort, the necessary filling in the blanks is more immersive. Wolf (quoted in [34]) speaks of a similar process when commenting; "abstraction in classic video games invites one to participate in the mental construction of the game world, filling in for the games' shortcomings". Stalker [35] speaks of the abstracted pixel aesthetics of JODI's Jet Set Willy Variations (2002) stating that the work highlights the mechanics of code while directing the player toward the surface pleasures of pixels and nostalgia. Bernstrup [36] similarly argues that the abstract pixels of older games make them more real than modern "photorealistic" games. The use of white noise, sine waves and other computer-generated sounds in the creation of ambiences, voices and weather effects in YNB attempts to create the auditory equivalent of this "pixel effect"; an auditory space that hovers between the real and abstraction.

In her article It's Time for Games to Move Beyond 'Cinematic', Dillon [37] concludes, "Now our games can sound like our movies do. That particular bridge was crossed some time ago. What next?" This question has been partially answered by a move away from realism towards retro visuals and sounds, even though computer capabilities are advancing. As with the resurgence of pixel art in modern games, the music in YNB revisits the past through its seven pieces of chiptune-esque music . YouTube allowed me to revisit the music of videogame composers such as Jonathan Dunn, Rob Hubbard and Martin Galway, who inspired the style of the music in the game.

The music serves a variety of functions; to promote nostalgia, to synergise with the imagery, to function as diegetic elements in puzzles, and to steer the player toward contemplating themes (discussed below). The music was created using a collection of software plugins that emulate the sounds of old computers and gaming consoles. In essence, the music and sounds in YNB exists as a historical collage of the retro gaming sounds that were prevalent in my childhood. In fact, the entire game can be understood as a historical collage of sounds, images (e.g. the David Lynch poster in the apartment), experiences and life lessons.

Another common discussion in game art relates to the relationship between the author/s of the game and the player. With regard to the author, Adams [38] asserts that art requires an artist to be taken seriously, and that it needs a prime visionary as with directors in cinema. Flanagan [39] observes that "games imprint our culture with the motives and values of their designers", therefore, a certain communication between player and author is unavoidable. Bissell [5] similarly states, "a presiding intelligence exists within the game" that invites comparison with other narrative media. He later describes being glad of the "hovering authorial presence" when gaming. I hoped to imprint my own creative style, humour and concerns onto YNB through the design of the imagery, sound, music and interactive events. However, the reception of video games is highly fluid. Collins [32] notes, "the participatory nature of video games in other words potentially leads to the creation of additional or entirely new meanings other than those originally intended by the creators by not only changing the reception, but also changing the transmission".

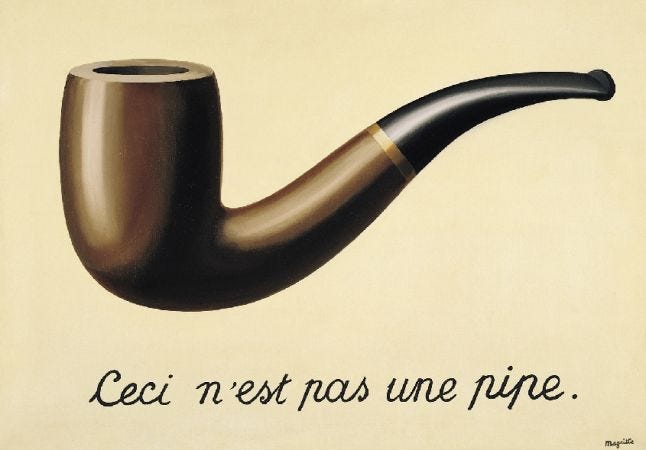

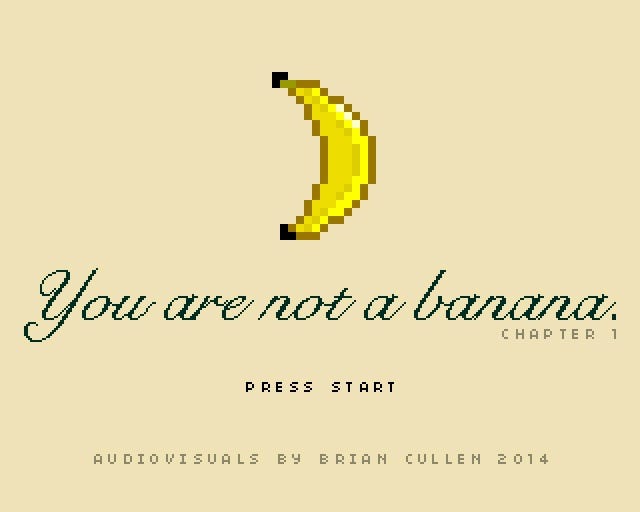

The title screen puzzle in YNB exemplifies how a sense of authorial presence can be incorporated into a game. The title screen alludes to René Magritte's Ceci N'est Pas une Pipe (This is not a pipe), in which a painting of a pipe is accompanied by the text of the title. The contradiction between the image and the text instigates a semiotic game between the author, artwork and viewer.

In YNB the player is confronted with a pixel art image of a banana that is accompanied by the text 'You are not a banana'. When the player presses ‘start’ they begin the game as a banana that cannot interact with the game environment (a one room apartment). In addition, the game reverts back to the title screen after fourteen seconds. Hint arrows do not appear until the title screen reappears for the fourth time. The arrows suggest that an alternative character can be selected by pressing the directional keys. When the left or right key is pressed a human character replaces the banana on the title screen; this character can interact with the game environment. The title re-contextualizes Magritte's painting as a video game puzzle.

A number of tasks in YNB deal with the mundane and everyday. In the initial sections the main character informs the player that he is hungry and needs to buy milk for his cornflakes. His thoughts are read via textboxes. This inner monologue is silent. Collins [13] discusses the merits of omitting the sound of a voice altogether so as to allow the player to imaginatively fill in the gaps. However, the character-to-character conversations in YNB are vocal. I felt there was a poetic charm in depicting voices using simple patterns of tones; as if the player is hearing the 'noise' of voices for the first time.

In general, text provides a human context to the simple arrangement of pixels on screen. If the character passes by a table full of letters, he laments that neither an employment cheque nor a valentine's card have arrived. Later in the game a snail moves and sings outside of an art gallery. The game character questions the reality of the snail, "Is this an artwork? Or am I losing my mind?" This line reflects my own anxieties regarding the reception of the game by both the academic and gaming community.

The main character informs the player that to leave the apartment he must listen for the keys' distinctive rattle but that in order to hear he must switch off the music in the apartment above. The idea of listening for the keys aims to highlight the active role sound plays in our lives (see [40]). Many of the puzzles in YNB are structured around sonic narratives and can only be completed by listening. To turn off the neighbour’s music the main character needs to flip a switch on the circuit board in the hallway. The sound of the switch being flipped stands in for the absence of a visual animation of flipping a switch. The player is given enough information through sound to compensate for the visual gaps.

After the music stops the player must return to the apartment and listen for the keys. The player can close the eyes of the main character by pressing the spacebar. A silhouette of an eyelid closing over the screen represents the closing of the main character's eyes. This eyelid can open and close with subsequent presses of the spacebar. Despite incongruities between the location of the eyelid and the actual location of the main character, a link between the character and the player's ability to see is established. This further exemplifies the player's ability to combine discrete perspectives into a coherent whole.

The opening and closing of the eyes is accompanied by a change in the audio aesthetic from retro to realistic. The retro aesthetic pervades the entire soundscape except when the eyes of the main character are closed. The realistic sounds were created from personal sound recordings. When the eyes are closed the main character can be heard bumping into objects; this was the sound of the author bumping into equivalent objects around the home. If a bang is accompanied by the rattling of keys the task is complete and the main character can leave the apartment. As apparent in YNB, video games allow for the interactive juxtaposition of two auditory aesthetics whereas in traditional mediums maintaining a single non-interactive aesthetic is more common. Video games also allow for an interactive documentation of ones auditory and/or visual environment.

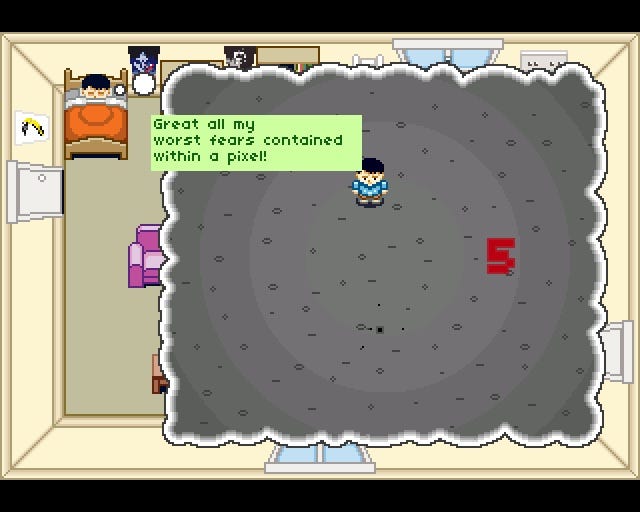

Once the keys are acquired the main character can exit the apartment. To go to the shop the main character must unlock his new bicycle. However, he needs a powernap to remember the combination and must go to bed. In the dream sequence the player needs to collect three numbers whilst avoiding a randomly moving black pixel, which according to the game character contains all his worst fears. If the main character is killed by the pixel, the dream ends and the colour drains from the sleeping character's face. Dying in one's sleep and facing one's worst fears are just some of the alternative themes included in YNB.

There are other instances where complex entities are symbolised by audio-visual objects or presented through audio alone. During the circuit board task the player has a choice between flipping one of two switches. If they choose the wrong switch an angry neighbour punches the main character, turns the power back on then returns home. Fluctuating white noise and synthesized notes represent the sounds of crowds and sports commentary coming from the angry neighbour's television. These simple sounds allude to a living space that the player does not see in the onscreen imagery.

In addition, the punching sequence functions in a contradictory manner akin to the text and imagery of Magritte's Ceci N'est Pas une Pipe. The punch acts as a reward for making the wrong decision rather than a punishment. Empathy between players and game characters does not always exist and therefore cannot be taken for granted. Other examples show us that violence in video games is far removed from the horrors of violence inreal life. For instance, Martin [1] remarks that shooting someone in GTA is fun and that video games do not make people angry. McGonigal [41] speaks of the joys of watching the monkey fly off the edge in Monkey Ball and coins the term "positive failure feedback" to describe such sequences.

There is small number of games that deal with everyday or personal narratives. In reviewing a game that deals with living with an alcoholic father, Meiser [42] comments, "in the end, Papo y Yo achieves what most modern games cannot. You truly feel emotionally connected to Quico the entire game." However, it often proves difficult to incorporate narrative with gameplay. Bissell [5] states, "the story force wants to go forward and the "friction force" of challenge tries to hold story back" and [5] concludes that authors should "... think of themselves as shopkeepers of many possible meanings ..."

I resorted to constructing parables/fables out of gameplay events in an attempt to achieve a balance between gameplay and narrative. The retro aesthetic seemed forgiving in relation to incongruities between narrative and gameplay. As a child in the 1980s I enjoyed figuring out the meanings of Aesop's fables. Years later, my brother told me a story that mirrors an Aesop's fable. The story goes as follows.

My brother, the proud owner of a new bike, was cycling to a corner shop to buy milk when he noticed a cyclist on an old bike ahead of him. He decided to show-off and cycle as close and as fast as possible past the cyclist. He executed his plan with precision, startling the cyclist in the process. He stopped at the shop to buy milk. Upon returning to where he parked he discovered that an old bike had replaced his new one. He surveyed the street. The cyclist was cycling away on his new bike. My brother hopped on the old bike to catch the thief but the bike was too slow. The tables had turned; karma had whizzed past and startled my brother.

Hocking (In [5]) asserts that "finding a way to make the mechanics of play our expression as creators and as artists..." is most important. My brother's story is retold in YNB in an attempt to illustrate how everyday narratives can be incorporated into traditional adventure games. To 'gamify' the story, the player must dodge various obstacles and collect wrenches on a busy roadway. When the player collects the last wrench the main character speeds past the other cyclist. In a later level, the cyclist speeds away on the main character's new bike. Although the exact narrative is compromised by the inclusion of 'gamifying' elements, the underlying morality of the event remains (see [43]). The main crux of the story unfolds through gameplay and, as with Aesop's fables, the broader meaning of the event is left to the player to interpret.

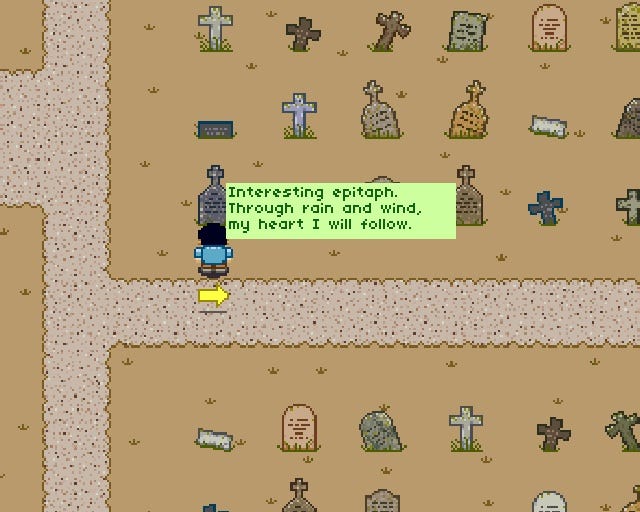

While I believe games are currently incapable of depicting issues of death in a manner as directly moving as cinema, they can encourage contemplations of death. Condon [44] observes in relation to the media, desensitization and his initial inspiration for his game mod Adam Killer (2000), "Death had become a floating signifier". In an interview Jade Raymond [45] remarks "I think for example it would be very interesting to have a game where the main character is very old and so even walking to the bus stop is a challenge." Tale of Tale's The Graveyard actualises Raymond's idea. In The Graveyard you play an old lady who walks slowly though a graveyard; the aim is to guide the lady toward a bench so she can rest. Kohler [46] states, "The value here isn’t the gameplay, it’s the carefully crafted aesthetic experience and its (successful, in my case) attempt to draw an emotional response from the player." McGonigal [41] describes a game she invented in an actual graveyard for real players entitled Tombstone Hold'em. She [41] proclaims this game encourages a meditation on death and a realignment of priorities, a process akin to a phenomenon researchers refer to 'posttraumatic bliss'. Flanagan [39] states that more serious games like Hush [47] and Darfur is Dying [48], which deal with accounts of Genocide in Rwanda, can provide "experiential truth", and have "... alternative goals such as meditative play...". While the subject of death in YNB is firmly placed in the everyday the graveyard puzzle was designed to examine the roles of 'experiential truth' through gameplay and the possibilities of 'meditative play'.

Certain tactics proved useful when attempting to communicate more complex themes. While I was attending a drawing class in the late 1990s, students were asked to draw 'love'. To express the ineffability of love, almost everyone (including the author) drew colourful abstract scribbles. However, one student drew a large red heart. The teacher observed that the heart symbol could at least be understood to represent love, unlike the class's incomprehensible scrawls. The merits of sometimes thinking ‘inside the box’ for the purpose of communication was a valuable lesson to learn. The graveyard scene in YNB uses morbid curiosity (a common behavioural trait in gaming), symbolism, pathetic fallacy and associations between sound, color and music, to provide the player with series of understandable events. Although the experience is open to interpretation, I sought to encourage the player to mediate on themes of life, death and gaming through gameplay.

The graveyard was designed to be infinite in size. The headstones are randomly arranged. To avoid the player getting lost, an arrow directs the player toward a headstone that reads, "Through rain and wind, my heart I will follow." When the main character reads the headstone another arrow directs the player to the right. On the player's first playthrough the purpose and destination of the journey is unknown. As the player travels into the graveyard a number of tactics imbue the scene with a sense of artificial or symbolised dread; the light in the scene darkens, the camera zooms back, rain pours, wind (white noise) howls, grey clouds roll past and off-key music (similar to the creepy music in the Super Mario games) builds. Once the player travels deep into the graveyard the music fades and only the sound of a heartbeat can be heard. If the player moves the main character in the correct direction (thus speeding up the heartbeat) they will discover an open grave (positioned at randomized locations each time the game is played). If the player approaches the grave a burst of flowers blocks their path, a harp glissando sounds and the lighting and color of the graveyard brighten. If the environment could speak it would state: 'It is not time yet. The real death we all face has yet to come. Continue playing.' The player then must get back to the activity of living, of engaging with the game world. In addition to a burst of flowers and color, a robin flies past and drops an art museum ticket on the ground. When the player retraces their steps to exit the graveyard a more positive musical score fades in. This music is later replaced by the sounds of the city, which get louder as the main character approaches the exit. On the journey back, there is no rain or wind. The grass is a luscious green and peppered with flowers. It turns out that the epitaph and the mystery of the infinite graveyard, like the bicycle story, functions as a fable, a fable relating to optimism and to getting on with one’s life including the mundane tasks of everyday living.

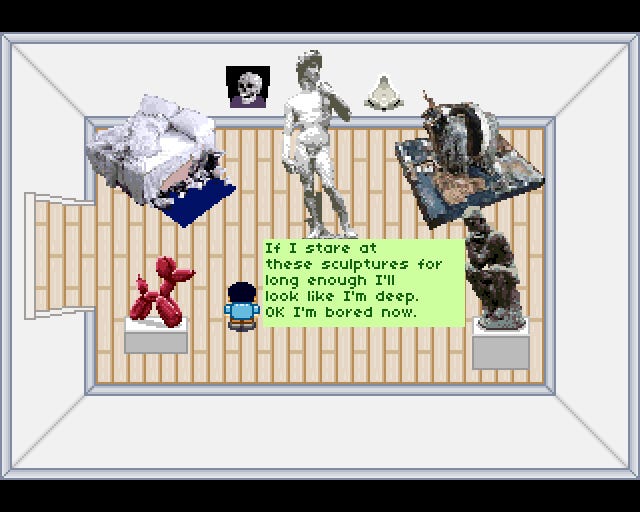

Many authors have displayed a general unease with video games relationship with the art world. JODI [49] comment that the most interesting work is separate from the "specialized digital art system" of festival and competitions and the "big art" and "big technology" family. There is also unease with the sacredness assigned to the museum space. Isbister [30] states, "So far as absorbing art, personally I think of the physical museum-going as similar to church - people act as if they are in a sacred space - reverent and cautious" and that "touching is usually taboo". Historically surrealist artists and activists, such as Duchamp and Cahun, sought freedom from traditional systems, what Flannagan [39] describes as "overly controlling aesthetics". She later states that "for many of the fluxist artists, play and the "joke" evolved as a methodology, moving interaction and audience participation away from the galleries and traditional theater environments and creating for the first time a kind of multiplayer artistic play space and environment." Videogames constitute a similar 'artistic play space'. Videogames align with many of the ideals of surrealist and activist art; videogames are everyday; they are humorous; they incorporate play and social connection; they can also incorporate collage/montage, ideologies and facilitate craftsmanship. The final section of YNB seeks to navigate a discussion of video games and art though gameplay involving the museum space.

The main gallery contains four paintings and a print; Starry Night (Van Gogh, 1989), The Weeping Woman (Picasso, 1937), Number 1 (Pollock, 1949), The Persistence of Memory (Dalí, 1931) and Turquoise Marilyn (Warhol, 1964). The works have had many conceptual frameworks attributed to them by historians, critics and even other artists. Placing the works into a video game adds another conceptual layer, giving them a new mode of existence and means of appropriation (i.e. navigable montage). My initial encounters with such works were in textbooks and on television. When I finally experienced the 'real' works my perception of them was distorted by my preconceptions. The works appeared odd; the originals seemed like fakes.

To progress the player must cause the museum janitor to appear by viewing all five art works. Each work omits a distinct sound. The sounds are panned in relation to the main character and reduced in amplitude as the character moves away. Therefore the sounds act as a sonic and spatial memory of which works have been viewed. Each sound contains a conceptual link. The Dali painting, which depicts melting clocks, is accompanied by a temporally undulating loop of synthetic plucks. The Warhol print is accompanied by a machine-like repetition reminiscent of the movements of a screen-printing press. The sound serves as a function tool but also sparks a debate regarding digitally mediated representation (see [50]).

Upon viewing the Pollock painting the main character states, "It's as if the entire universe is just made up of pixels." The splashes and strokes in the Pollock painting are missing in the YNB pixel art version; Pollock's interactions with the work have been erased. This loss of information is exemplified by the main character's misinterpretation of the work. When the main character comments on Turquoise Marilyn he refers to the new context given to the work by the game, "Huh, a virtual version of a digital version of a print of a photograph of an icon." Once the player discovers that the museum door is jammed, the main character proclaims upon re-approaching the same works, "No time for art. I need to get home before my milk turns sour." In other words, the meanings attributed to the works are also dependent on the current predicaments of the player/main character, which include past exposure to the work and more pressing priorities; in the main character's case, a need to get home and eat cornflakes. The inclusion of such elements in YNB shows that video games can tackle complex discourses such as the digital consumption of the traditional arts.

In reference to the use of artworks in a Sims Online installation, Isbister [30] states, "I guess in this case Simulation ends up activating and giving the power back to the work as opposed to diluting it". In a similar way, the sculptures in YNB are re-contextualized by been pixelated, placed in the same room together, and by the presence of the main character. The body shapes of the main character and that of Michelangelo's David (1501-1504) clash, the hybrid state of Rauschenberg's Monogram (1955-1959) as a painting/sculpture is given a third digital dimension, and Emin's My Bed (1998) is cleansed, lacking the necessary detail to depict the bodily excretions of the original. Many of the art works in YNB, such as Hirst's For the Love of God (2007) and Koon's Balloon Dog (1994-2000), acknowledge Hughes's [51] critique of art as big business and as commodity. Hughes warns that the very meaning of art and its true cultural value is in jeopardy, a sentiment shared by the author. May be videogames can address this imbalance by placing art/curious objects back in the home at an accessible price.

When the main character enters the Mona Lisa Gallery a crowd symbolic of "big art" and "big technology" family [49] blocks his view; although the actual player can see the painting beyond the crowd. The player enters a contradictory state of being able to see and not being able to see, at least in terms of empathy with the main character. This dual state acts as a metaphor for how previously obtained experiential knowledge of objects distorts our understandings of the presence of an original work; we can and cannot see the works for what they are. In other words, the works have lost their intended meaning. It also alludes to the accessibility of videogames in the home and online verses the accessibility of artworks in exclusive museum spaces. For example, a walkthrough [52] of YNB has received ninety five thousand views at the time of writing this paper. However, the reception the game is altered by the narrator’s commentary and play style.

The inclusion of the museum also functions to highlight society's move away from the physical world towards virtual pleasures. McGonigal's [41] describes this as a "mass retreat to virtual worlds". The artworks in YNB haunt the player from an increasingly distant physical past. This new 'gamified' exhibition may be the works' last exhibit. So who or what will get the attention of the art world next?

As touched on above, YNB explores the uncomfortable relationship between the everyday and the traditional museum space, including how art amalgamates movements such as indie game design. Once the player discovers that the exit door is jammed they must find the janitor. A secret door can be found in the hallway by closing the game character’s eyes and bumping into the walls. The secret door leads to the janitor's art installation. The janitor proclaims, "I've worked here for over forty years. Seen a lot of art, been learning. This is my most profound artwork! Oh! And it will get you home too!" He informs the main character, who is concerned about his milk going sour, that once viewed, the installation will make his milk taste even better. This risible discussion expresses a number of ideas. It attempts to assert the importance of the everyday (symbolized by the janitor) over the virtual worlds of overtly abstract academic discourse and obsessive gaming. You Are Not A Banana jokingly presents "the ultimate artwork", parodying many traditions in the art world, including artists never-ending competitive quest to produce more sensational experiences. This critique also extends to our overly competitive consumer culture in which consumerism regularly masquerades as creative revolution. However, only the main character, partly a figment of the player’s imagination, experiences the work. The player never truly experiences the ‘profound’ installation. Fenty [33] refers to the "deferred dream" in D. B. Weiss' book Lucky Wander Boy (2003) in which the protagonist chases the ultimate classic videogame experience; an experience that once attained, the reader is excluded from. The janitor installation suggests that the most interesting aspect of the museum is the activities and imaginations of its inhabitant in combination with the artworks - a player engagement relationship. It is the audience that supplies thought to Rodin's The Thinker. Finally, the hidden existence of the janitor's ingenious installation reveals that other sources of meaning can be found beyond the walls of the museum and other such institutions.

In the closing credits the main character finally eats his cornflakes. Initially, the sound of the character eating comprised of a selection of randomly varying sounds. Later, I decided that the eating sound should be comprised of only one sound to assert my ambivalence with the cycle of desire and consumption prevalent in society, especially in relation to game and hype for upcoming titles. A similar ambivalence is evident in Eddo Stern's Fort Paladin: America's Army (2003). Here robotic fingers play a violent scene in the game where the main character dies over and over again. Flanagan [39] describes this work as expressing "the futility of agency in closed systems". The closing scene of YNB aims to reassert the mundane nature of the ultimate goal of the game (to consume a product e.g. cornflakes) and believing one could derive profound pleasure from it.

The ending was partly inspired by the surprise ending of the 1989 game Snare [53]. The prize at the end of this difficult futuristic trial turns out to be an advertisement for a Terry's Chocolate Orange. This ending parodied advertisements at the time, while emphasizing that it was the act of playing, desiring a resolution and struggle to get to the end that counts and that the prize could never live up to expectation. In reaction to having his atoms deconstructed and reconstructed by a teleporting art installation the main character remarks; "That was kinda meh, but eating these cornflakes with enhanced milk, that will be profound”. It is assumed that his hunger will never be satisfied.

Martin [1] reflects, "video games compile all of the art worlds tools into one medium". This paper proposes that video games can be added to the long list of tools at the artist’s disposal. In fact, the conceptual processes used to create YNB, such as layering imagery and the construction of sound worlds, are almost identical to those used in photography, screen-printing and in video and computer music production. Video games can be understood as digital hybrids of the fine arts where temporal and rule-based interactions are added to traditionally more fixed practices. Recent and well-received games such as Depression Quest [54], Gone Home [55], The Stanley Parable [56] and Device 6 [57] combine text, sound, imagery and spatial navigation and exemplify how video games fuse the traditional arts. Aside from functioning as a cultural montage, YNB seeks to assert the exploration of the everyday as an untapped resource for novel gaming ideas and scenarios. In addition, it attempts to include more socially/culturally meaningful interactions relating to death and critiquing the art world. In essence, YNB follows a game design model in which "human concerns, identifiable as principles, values, or concepts, become a fundamental part of the process" [39].

Adams [38] states that great art challenges the viewer, expands his or her mind, and that video games could be designed for the player to obtain a new kind of understanding rather than simply to achieve something. You Are Not A Banana hopes to be part of an increasing list of games that seek to explore the possibilities of video games as art. Designers and artists today are at a crucial point in history where traditional practices are colliding with access to new video games technologies. It would be a great shame for both art and gaming to ignore the opportunities afforded to us by combining and evolving traditional practices with these recent technological, societal and cultural shifts.

The author would like to thank Neil Randall and Karen Collins for their help and advice. The author would also like to thank all those at The Games Institute and IMMERSe, especially Agata Antkiewicz and Megha Bhatt, for their kind support.

Note: You can pick up the latest version of You Are Not A Banana on Steam here or check out the demo for my latest game Mayhem In Single Valley on IndieDB, GameJolt, or Itch.io.

[1] B. Martin, "Should Videogames be Viewed as Art?" in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[2] A. Clark, G. Mitchell, "Introduction," in Videogames and Art. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[3] J. Andrews, "Videogames as Literary Devices," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[4] A. Smuts, "Video Games and the Philosophy of Art," ” [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.aestheticsonline.org/articles/index.php?articles_id=26, 2005

[5] T. Bissell, Extra Lives. New York: Vintage Books, 2011.

[6] M. Grela, "An Interview with Davey Wreden Developer of "The Stanley Parable"," [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://beta.escalatingregisters.com/article/an-interview-with-davey-wreden-developer-of-the-stanley-parable/

[7] J. Jones, "Sorry MoMA, video games are not art Exhibiting Pac-Man and Tetris alongside Picasso and Van Gogh will mean game over for any real understanding of art," [Web site] [2009 Apr 2], Available: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/nov/30/moma-video-games-art

[8] J.Maeda, "Videogames Do Belong in the Museum of Modern Art," [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.wired.com/opinion/2012/12/why-videogames-do-belong-in-the-museum-of-modern-art/

[9] A. Stockburger, "From Appropriation to Approximation," in Videogames and Art. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[10] D. Quaranta, "Game Aesthetics - How Videogames Are Transforming Contemporary Art," in Gamescenes Art In The Age Of Videogames, Edited by M. Bittanti, D. Quaranta. Milano: Johan & Levi Editore, 2006.

[11] H. Lowood, "High-Performance Play: The Making Of Machinima," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[12] Pippin Barr, Curious Games, Center for Computer Game Research IT Univ. Copenhagen, [Website] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://vimeo.com/37296318

[13] K. Collins, Playing with Sound A Theory of Interacting with Sound and Music in Video Games. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

[14] Andy Clarke, "An Interview with Brody Condon," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[15] Ed Key, Proteus, Curve Studios, 2013

[16] "Proteus" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.visitproteus.com/

[17] A. Garbut, "Rockstar North’s Aaron Garbut on the making of Grand Theft Auto V – our game of 2013," [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.edge-online.com/features/rockstar-norths-aaron-garbut-on-the-making-of-grand-theft-auto-v-our-game-of-2013/

[18] Brendon Chung, Gravity Bone, Blendo Games, 2012.

[19] Brendon Chung, Thirty Flights of Loving, Blendo Games, 2012.

[20] A. Reading, C. Harvey, "Remembrance of things fast Conceptualizing Nostalgic-Play in the Battlestar Galactica Video Game," in Playing the Past History and Nostalgia in Video Games, Edited by Z. Whalen, L. N. Talyor. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2008.

[21] A. Barker, "We didn't own an Ipad" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HeEWtNaW6KE

[22] "Disconnect" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1433811/

[23] CBC News, [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/family-ditches-computers-lives-like-it-s-1986-1.1399224

[24] V. Tanni, "Nullsleep (jeremiah johnson) New York Romscapes, 2004," in Gamescenes Art In The Age Of Videogames, Edited by M. Bittanti, D. Quaranta. Milano: Johan & Levi Editore, 2006.

[25] "Maya" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://www.lukejerram.com/projects/maya.

[26] L. N. Talyor, Z. Whalen, "Playing the Past An Introduction'" in Playing the Past History and Nostalgia in Video Games, Edited by Z. Whalen, L. N. Talyor. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2008.

[27] C. Johnson, "Dad hacks Donkey Kong for his daughter; Pauline now saves Mario Princess: your Mario is in another castle" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2013/03/dad-hacks-donkey-kong-for-his-daughter-princess-pauline-now-saves-mario/

[28] C. Johnson, “"I am no man”: For Zelda-playing daughter, dad gives Link a sex change "Dad's favorite pastime shouldn't treat girls like second-class citizens"." [Web site] [2014 Apr 2], Available: http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2012/11/i-am-no-man-for-zelda-playing-daughter-dad-gives-link-a-sex-change/

[29] S. Johnson, Everything Bad Is Good For You How Today's Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter. New York: Riverhead Books, 2005.

[30] J. Pinckard, "The Isometric Museum: The Simgallery Online Project An Interview with Curators Kathrine Isbister and Rainey Straus," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A.Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[31] Melanie Swalwell, "Independent game development two views from Australia," interview with O. Julian and Kipper, in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke and G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[32] K. Collins, Game Sound An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2008.

[33] S. Fenty, "Why Old School Is "Cool" A Brief Analysis of Classic Video Game Nostalgia," in Playing the Past History and Nostalgia in Video Games. Edited by Z. Whalen and L. N. Talyor. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2008.

[34] M. T. Payne, "Playing with Deja-New "Plug it in and Play TV Games" and the Cultural Politics of Classic Gaming," in Playing the Past History and Nostalgia in Video Games. Edited by Z. Whalen and L. N. Talyor. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2008.

[35] P. Stalker, "JODI Jet Set Willy Variations, 2002," in Gamescenes Art In The Age Of Videogames. Edited by M. Bittanti and D. Quaranta. Milano: Johan & Levi Editore, 2006.

[36] Francis Hunger, "The Idea Of Doing Nothing: An Interview With Tobias Bernstrup," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[37] K. Dillon. "It's Time for Games to Move Beyond 'Cinematic' Hollywood has been a huge influence on video game scores, but are there better options for our medium?" [Web site] [2009 Apr 2], Available: http://ca.ign.com/articles/2012/03/19/its-time-for-games-to-move-beyond-cinematic-2

[38] E. W. Adams, "Will Computer Games Ever be a Legitimate Art Form?," Videogames and Art. Edited by A.Clarke and G.Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[39] M. Flanagan, Critical Play Radical Game Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2009.

[40] M. Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Trans by C. Gorbman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1994.

[41] J. McGonigal, Reality is Broken Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. Penguin Books, 2011.

[42] C. Meiser, [Web site] [2009 Apr 2], Available: http://pikigeek.com/2012/08/28/papa-y-yo-review-imagination-runs-amok/

[43] E. Chew, "How does the interactive aspect of an autobiographical video game affect how someone's life story is told?" [Web site] [2014 Apr 2] https://www.academia.edu/6730626/How_does_the_interactive_aspect_of_an_autobiographical_video_game_affect_how_someones_life_story_is_told

[44] Rebecca Cannnon, "Meltdown," Interview with B. Condon, Videogames and Art. Edited by Andy Clarke and Grethe Mitchell, Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[45] J. Raymond, [Web site] [2009 Apr 2], Available: http://metro.co.uk/2013/08/15/jade-raymond-interview-i-want-a-game-where-walking-to-the-bus-stop-is-a-challenge-3924701/

[46] C. Kohler. "The Graveyard‘s Ten-Minute Tale Of Death," [Web site] [2009 Apr 2], Available: http://www.wired.com/gamelife/2008/03/the-graveyards/

[47] J. Antonisse, D. Johnson, Hush, 2007

[48] Darfur is Dying, Susana Ruiz, 2006

[49] Francis Hunger, "Perspective Engines: An Interview with JODI," in Videogames and Art. Edited by A. Clarke, G. Mitchell. Bristol UK: Intellect, 2007.

[50] W. Benjamin, "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Editied by H. Arendt. Schocken, 1969.

[51] R. Hughes, The Mona Lisa Curse. [Web site] [2014 Apr 2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JANhr4n4bac

[52] Nilesy, "Nilesy is NOT a banana!!" [Web site] [2014 Apr 23] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcgFVqaGd7M

[53] Snare, Thalamus Ltd, 1989

[54] Zoe Quinn, Depression Quest, 2013

[55] Gone Home, The Fullbright Company, 2013

[56] Davey Wreden, The Stanley Parable, 2011/2013

[57] Device 6, Simogo, 2013

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like