Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extensive new interview, Dan Gorlin, the creator of the 1982 Apple II classic tells the story of its original development, ruminates on the PC game scene of the 1980s, explains why the '90s reboot failed, and discusses why the new Choplifter HD is the first reboot to work.

Poll a random group of 30-somethings who play (or used to play) computer games, and ask them to name a computer game author. Odds are at least one person will respond "Dan Gorlin."

It might not have the marquee appeal of a Shigeru Miyamoto or a Will Wright, but it's not a bad legacy for a teacher of African music who accidentally stumbled into video game development and hasn't shipped a widely-recognized title since 1982. But the unlikely popularity of Choplifter, combined with his name appearing on the packaging and title screen of its numerous incarnations, made Gorlin something approaching a household name -- at least within computer-owning circles.

Perhaps it was because Gorlin wasn't himself a gamer that Choplifter became such a hit. Though the game -- an arcade-style, reflex-based title where players control a helicopter rescuing prisoners -- allowed users to zap and blow up enemy targets, the game didn’t bother keeping score of these things because as Gorlin himself tells it, that's the boring part.

The goal of the game was instead to help others, which really made it stand out from the crowd in an era where space shooters with a rolling score plastered at the top of the screen was the norm.

Or perhaps it was the game's timing (coincidental, according to Gorlin) right after the Iran hostage crisis of the early 1980s, which was still fresh on everyone’s minds. Now everyone who was frustrated by the news could escape into fantasy and be empowered to rescue the hostages themselves.

Regardless, Choplifter is an undeniable classic, and a game worth revisiting and studying. This week, InXile Entertainment released a brand new reimagining of the game, Choplifter HD, for which Gorlin served in an advisory role: his first brush with the video game industry in some years. In this exclusive interview, Gorlin discusses the history of the original Choplifter, what he's been up to all this time, and how the changing mobile landscape is tempting him to return to game development.

I was really happy to see your name in a game again, but I get the impression this is less of a comeback and more of a side project for you.

Dan Gorlin: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I'm not really in the games industry, although I'm sort of working on Android projects on my own time. If there's a comeback coming, it's going to be on Android phones, and it's going to be sometime in the next six months or so.

Dan Gorlin: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I'm not really in the games industry, although I'm sort of working on Android projects on my own time. If there's a comeback coming, it's going to be on Android phones, and it's going to be sometime in the next six months or so.

But on this one, I was involved early on the design of this game, and I was involved in helping them get it to market, and PR, and stuff. And meeting the team, and working on it. But I haven't been a regular member of the team. I've sort of been like the honorary grand old man, hanging around going, "Wow, this is cool, you guys!"

I talked to a couple of the guys and they seem to have nothing but respect and admiration for the original.

DG: I know the team, especially Brian Fargo who, I think he's heading it up creatively, and he's also the CEO of inXile. It's just one of his favorite memories of games, and he's just excited to be part of the comeback.

It's something for the old timers, but the kids that are really young now -- maybe 25 or so -- I don't know how many of them ever played the original Choplifter. There've been so many versions since that. But it's just fun to be a part of history -- kind of like you're remaking history.

What was the genesis of the original Choplifter?

DG: Well, the original Choplifter... let's see. What was I doing at the time? I was a music student, I was studying piano at the California Institute of the Arts, and then I stopped doing that to work at Rand Corporation for three years, doing artificial intelligence computer research. So I was in the middle of this sort of back-and-forth -- like, "I don't know what's going on with life" kind of thing.

And I went to start selling my house. The Rand job ended, and I was just sitting at home with nothing to do, waiting, waiting for somebody to buy my house in Los Angeles. So I just started playing with the Apple II, which was brand new. My grandfather had one, and he loaned it to me, so that I could play with it. And six months later, there was Choplifter.

At first what inspired it, I think -- like I always do -- I just started playing with things that seemed like fun. Helicopters were always just something that I would stop and look at, the way people would stop and look at a waterfall, or a pretty bird. Helicopters just fascinated me. So right away I started building a helicopter, and the Choplifter code.

It was all in the in the summer, at the time, and as people love to point out, there was this neighborhood guy that was working on my car, and he was a Defender fan, at the time. And Defender had little men in it, and he used to tell me about the little men, and how much fun they were. And so that sort of put an idea in my head to add men, and things just really added up.

At some point, I had a fun little helicopter flying around, and I sent it off to Brøderbund, which was one of the big game companies at the time, and they loved it, and they flew me out there, and they started supporting the development of it, and pretty soon we had Choplifter.

I did want to talk to you a little bit about Brøderbund. I've learned more about the '80s, and the way games were designed back then. Will Wright spoke at the Game Developers Conference, for example, and he was talking about Raid on Bungeling Bay. It was exactly how you described. You send it to Brøderbund, they fly you out, and all of a sudden you're a game maker. Is that how the environment was back then?

DG: Yeah, it definitely was. Well, they were making games for the Atari 400 and 800, and that was a fairly successful market, and the Apple was a fairly successful market. That was when you could buy games in a computer store. You'd go in and they'd have a little rack of games in baggies. There were no high end boxes, or high end artwork, or any of that kind of thing. You'd open up your little baggie and there'd be a single sheet of paper, and a floppy disk, and that was the game.

I had never played any of those games -- I still don't play games. I'm not a game player. I love the game of making games, but I'm not a gamer, personally, so I'd never actually played games at the time, but it just seemed like a fun project. so I took it on.

And Brøderbund was Doug and Gary [Carlston] and Cathy [Carlston Brisbois]. They're all the children of a minister. They're really, really nice people. They're having a lot of fun with what they're doing, they're smart -- Doug had just come out of Harvard -- and they're just a fun group of people.

So the way they did it was, they'd see something that was like, it'd have promise, and they'd sort of engulf you with family love. It was a very nurturing environment. If you fly out, a lot of the guys would stay at Doug's house. Doug had like three huge dogs, and this huge house in San Rafael, north of San Francisco.

For a lot of the guys, he was kind of a father figure, really. And I noticed a lot of the successful software companies, they all had some sort of weird father or mother-like element in it. Somebody who really loved the programmers, and treated them with respect, and loved the games, and made everybody feel useful and happy. It was a great environment.

Actually, the Choplifter contract was -- it's a joke to look back at it now. It's like two pieces of paper, where they signed a huge royalty percentage -- which, at the time, they were just being really generous. And people thought they were being insane. But whenever we revised the contract, they always honored it. I always did whatever it was I was supposed to do.

It was an honest group of people, and as the company grew, it meant... that a company can maintain that environment. Whoever's in charge of a company's going to set the tone for the way the company winds up behaving, and for the most part, Brøderbund people are just a great place to work for. There's a real family environment, and nurturing environment. And then it all ended, as good things always do.

It sounds like when you started Choplifter, it was just the programmer in you just kind of screwing around. But was there a point where you realized like, "Hey, this might be a commercial product"?

It sounds like when you started Choplifter, it was just the programmer in you just kind of screwing around. But was there a point where you realized like, "Hey, this might be a commercial product"?

DG: Oh yeah. I mean, I told my wife at the time, I said, "I think I can make some money doing this." She's like, "Sure, whatever." She was an executive at Atlantic Richfield. She was like an oil company magnate kind of person. So I just quit my job. She had a perfectly good job. It was just the two of us, and I played with it for six months, and then I made some money.

I had a sense that I could make some money, because of the people who were doing it. No more, no less than anyone who is getting started today. You look at the market and go, "Hey, maybe I'll make some money."

The success of Choplifter surprised me. It was clear at the early trade shows. I don't know if you remember back then -- you were probably pretty young -- but the kids used to come to the trade shows, like the computer conventions, and you could put a game out running on an Apple II, and the kids would line up to play it.

And the first trade show where Choplifter was shown was, I think, at CES, probably. The kids were lined up around the block. So it was clear that this was going to be successful, but nobody had any idea how successful. It just sort of was one of those phenomenons.

A lot of us at Brøderbund were going, "Yeah, this is going to work out pretty well," but you never know until things until the rubber hits the road.

Choplifter came out in 1982. I always thought it was pretty unorthodox to have a game that early on that wasn't really a high score game. You were judged on other attributes. Was that an intentional way of differentiating yourself, or was that possibly just a product of you really not being much of a gamer yourself?

DG: I think it's both, really. I knew that games had high scores. I had played a couple games. I didn't spend a lot of time on it, but it was obvious that that was part of the genre. But even then, I was 28. I wasn't a kid, so I remember thinking, "In entertainment, if it's good, novelty is always going to be worth something."

Just changing things around just to mess people up isn't going to translate to sales, but if you've got an idea that's better, it's to your advantage if it doesn't quite work the way other things work. Because if there's a way that it's going to stand out...

And I never was the least bit interested in scoring anything. To me, the only thing that was interesting, when I finally got these men in there running around and stuff, it's like, "Well, let's see how many we can rescue." But it's like, God, I didn't care how many planes I killed. I didn't care how many tanks I killed. I could care less about that stuff.

So to me, it just wasn't interesting. It was boring to try and score anything. That makes this an interesting human environment. It makes it a community. Oh, I'm trying to be a useful part of the community. I want to help people. Even today, it's hard for me to imagine why people love games where the idea is to just blow things up. I get bored with those in about 10 seconds, personally.

I agree with you, and I think that that's why Choplifter is still remembered today -- because how many little Apple II games do they still talk about today?

DG: The other thing to remember is it's such a different world when you're developing a game on your own, which is the way it was done back then. It'd still be a couple years before games were developed in teams, and when you're on your own, nobody's going, "Well, that's not the way it's done." "Well, we don't have any market data to show that kind of game is good." You don't have to deal with that stuff at all.

You did the game your way, and you send it off to somebody, and if they like it... The Brøderbund people were always really open minded. They're intelligent people, so they saw something different, they'd go "Wow!" They'd sit down and play it, and either it was fun or it wasn't fun. It was kind of a no brainer.

The one day that everybody remembers is -- I was in the room for this one -- is when Tetris came through, submitted to Brøderbund. And everyone was just, "What? It just isn't really going to be such an interesting game," and of course it turned into a huge amazing success.

But they had a lot of great success stories, and almost always it was them finding something that had a seed of something great, and then nurturing the people, and really giving them the time to just finish it off. And nobody was happy until it was done. There was no kind of marketing pressure, or, "It's got to be done for Christmas." None of that kind of thing. Just, "When it's done, it's done."

That's great.

DG: Really, I don't know how they'd do that with the budgets of today's games. I mean, there was no budget. Brøderbund, they'd give you an office, maybe. I didn't even have that. I had my own house, and I was working out of my house. It's not like they had a huge overhead for doing this kind of thing. There overhead was just the time they spent caring about it, and you hanging around at their house, and sleeping at their place, and using their hot tub. And it was fun for everybody.

So did they fund it at all, or was it just purely royalties?

DG: It's purely royalties, and most of the projects were like that. Now Print Shop, those two guys, they worked with Brøderbund in the offices for about a year. So in that sense, I guess they did fund it. I don't think they were paying them anything. I think they just thought it was a great idea, so they provided the space to work on it, and those guys had a royalties deal that was probably just as good as mine, and they did really, really well.

Lode Runner was around the same time, and Doug Smith already had Lode Runner already kind of running on some of the networks at the time, so he already kind of had a working version. He was around the offices, and I remember one night, we stayed up all night and I did the music for his Atari version of Lode Runner -- we were all sort of helping each other out. I don't think that was funded either, in any way, except for just some office space and time.

It was only later that they started putting money forth, and in those situations, the royalties were much less, and it actually there was a lot of tension caused when they finally started to get real about, "If we're hiring people to work, they're not being hired for royalties. They're being hired for pay." So when you offer people royalties and they say, "You're going to get rich," but they're also giving you salary, they never get rich. And sometimes that made people very angry, and that was a very difficult transition for the industry, I think.

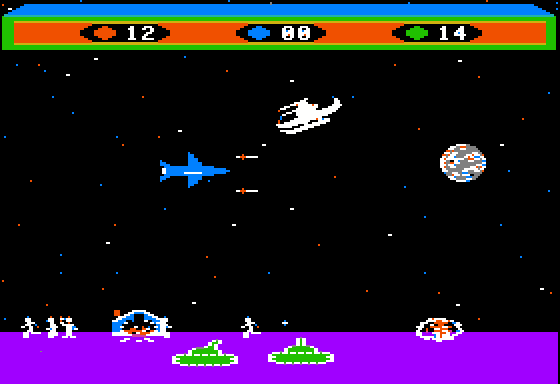

Choplifter! (Apple II version)

Yeah, I bet. So you, yourself, said that Choplifter was a very simple game, but are there any hidden behaviors, or little touches in the original that people might not have noticed?

DG: I don't think so. I think it was all pretty out in the open. If there's anything interesting about it, you would never see the same game twice. There was nothing really scripted. Even today, when I go to rent a game, the idea of scripting somebody's motion is just, it's a foreign language to me.

There's a character, it looks around in its environment every second, and decides what to do with that moment. And so there's a certain kind of organic feeling that might have come from just the way that I approached that. Each character was his own little world. He'd look around, he'd go, "Oh, this is what I've got to do now." And so as a result, you just never got the same game twice. You can do that even with a simple game. I think that's about the only element I can think of that people might not have noticed.

That was something that Choplifter did that was actually unique for the time. Arcade games had that kind of thing, or limited versions of it, but with Choplifter, it would actually play itself. I wrote a player as a program. He was kind of moderately good, and he could usually get almost through the first level -- a different game every time, so it made for an interesting splash screen.

Yeah, because you still have the emergent behavior of everyone in the world, even though the player is scripted, right?

DG: He was looking to see what was around, and going for it. It all became very organic.

I don't know any cheat codes or any of that kind of thing; there was some cheat codes, but I can't even remember what they are. Screen upside down -- good stuff.

Was there anything sort of left on the cutting room floor? Things you couldn't implement?

DG: Oh, I started off doing a 3D Choplifter. That was my first intent -- to make it 3D. And there were no vector graphics at the time. It was just raster, so I had to quit real really quickly on that score. Yeah, there was tons of stuff. Did you ever play Airheart or Typhoon Thompson?

No, I haven't, though I was going to ask about those. I never got around to it.

DG: They're also very similar. I had huge plans for all of them, and then, at some point, you just go, "Okay, what can we do in my lifetime?" Those actually were 3D games, and it was still in the raster world, and I was driving myself crazy trying to get that done.

So the only reason that I put that kind of energy into it is that, at that point, I was making too much money, and I didn't really have to worry about reality. Otherwise, I would have gone out on the 3D thing much earlier. Now, I'm just strictly in 3D, and I love 3D. I love everything about it. It's just really hard to make a game out of it.

This isn't the first revival of Choplifter you've been involved with. The other one was called Choplifter 3D.

DG: Well, I did have a deal to do a PC version of Choplifter with what was Spectrum HoloByte, and then MicroProse. It was sort of in the middle of the industry consolidation, so in the eight or nine months that the project lasted, I think the original project was bought and sold three different times. The companies were buying each other up, and at some point somebody decided, "We don't want this on our roster," and so the project was canceled.

It was a 3D version of Choplifter and we were a pretty far way into it. I don't know -- I think it would have been an amazing game, but it was not turning out like some people imagined it should. A lot of people imagined Choplifter as this war game, where things blow up, and you have scores for blowing things up, and we simply weren't doing that.

As one guy said at one point, "Wow, it's Choplifter!" I said, "Yeah. What were you expecting?" And what they were expecting was movies and lots of animated cutscenes, and lots of things exploding, and lots of scores -- just like every other war game that was out there, which I had no interest in doing at all. So there was some friction, at the point where there were a lot of middle managers involved. And the company kept changing. Eventually, the project, somebody decided that it wasn't what they were going to be doing with their company, and they wound up owning it, so they didn't do it.

Bringing that Choplifter aesthetic into the world of the late '90s, I guess, where there were these tried and true formulas. The people that were middle managers of these companies, I think a lot of them came from Pepsi, or they came from the ROTC. They were game players, but they knew what game players know. They weren't visionaries.

If there were visionaries in the company they were off in a boardroom, someplace, and they didn't even know what was going on with the development of the project. And that was a big problem with the larger companies. You had to delegate a lot of your visionary functionality to middle managers, and middle managers, they're not the visionaries of any company, unfortunately.

When I think of your video game career, I just tend to think of those three titles: Choplifter, Airheart, and Tycoon Thompson. But you did a little bit after Tycoon Thompson, right?

DG: Yeah, I've done other things with other game companies, working as a programmer for projects. Or mostly there were a lot of licensing deals at the time. What I wound up doing for a living was licensing deals, and I did that for a while, and then it just was really boring for me, so I moved to other things. But yeah, there were some LucasArts projects I got involved in.

There were little things for Electronic Arts, and so forth, and I did some conversions, too. I actually did one of the Prince of Persia conversions. So I took little jobs here and there, just to sort of move myself around. But mostly in terms of the game industry, it's just the games that I did as original titles. And I wouldn't cite any contribution I had to any team project that was memorable or exciting.

I don't know if you remember the selling numbers, but Choplifter was... Back in the day, VisiCalc was the only program that had mega sales on the Apple II, and what Choplifter did from an industry perspective, it that changed all that. Because it was the first game that came along and took the number one spot, and it did that for several years.

So at the point where Choplifter was doing that, there were a lot of companies going, "Oh, okay. It's time," and they all wanted to get in on the games market. And none of them had any idea how to do that, so there was a lot of what I call "stupid money" flying around.

People would literally walk up to me on the street and say, "I'll give you a million dollars to start a game company for me," and I would literally say, "You may as well give it to that guy laying in the gutter over there, as far as what you'll get from your money. You just don't understand what you're doing."

But companies were doing that all over the place, and a lot of people, their livelihood became getting money from these big companies that didn't know what to do with their money, but they really, really, really wanted to be in the games industry.

Boy, that is something that has not changed at all. So from your perspective, why was Choplifter that massively successful?

DG: Probably the biggest thing was the tie-in with the Iran hostage crisis, at the time. I know you weren't around for that, but we'd been living with the Iran hostage crisis for like two years. Everybody heard about it over and over again, every day. Everyone was frustrated by it. There were guys over there, we couldn't get them, and we couldn't do anything about it. We tried, and we failed miserably, and so all of a sudden here was a game where you went and rescued the hostages. It was big.

It was also a game that had the reputation of being non-violent. What that meant was, you're trying to rescue people, not kill people. So between those two things, every kid wanted it, and every parent was willing to buy it for them.

Sometimes I would go in a computer store, and I'd just stand around, and eventually a mother would walk in and say, "I want to get that helicopter game for my kid -- the one where you rescue people." And you could just see this happening on every street corner, and every city.

So there was a magic element, a magic tie-in to what people were frustrated about at the time, plus the fact that it was something that parents could feel good about buying for their kids, who were going to play games whether they wanted them to or not.

I want to emphasize that I think being a really high quality product is important in that environment than if you can catch people's attention. It's got to be something that really works, is really well done, polished, for it actually to benefit from that attention. Just capturing that attention isn't enough to make a blockbuster. But once people get it, if they're really happy with what they got, then you've got something that's timeless.

And, from my perspective, it's designed like an arcade game. I think that simplicity probably added a lot to it.

DG: Yeah, yeah. Simple to learn, hard to master. And people still wrestle with that, because people that build games, they're gamers. To them, simple to learn means it's only got fourteen control sequences that you have to remember. And to your grandmother, simple to learn means something completely different.

That's always, I think, a source of contention in game design. I think very few games these days are actually designed for beginners, unless they're designed for children, in which case people get it. They've got to be really, really simple. I personally think all games can be really, really simple.

I agree.

DG: It doesn't mean that you're going to be easily able to master them, it just means you get started right away, and you can do stuff right away. That was a big design goal for Choplifter HD, and I think they pulled it off really well, and that's one of the things that they really wanted to try to hold onto from the original version. If Choplifter comes out, and it's massively hard to learn, it's not Chpolifter, really.

This is the first Choplifter I've actually been involved with, from a design point of view. The other ones were all licensing deals, so I didn't have anything to do with actually building them. But on this one, the team and I had a common sense of what we wanted to try and accomplish with it, so I think the results are pretty cool.

inXile entertainment's Choplifter HD

Where did this project come from? Have you just known Brian Fargo a long time? You said he was a fan of it.

DG: I have known Brian a long time. I met him decades ago, but he texted me. He started going, "We're inXile, we're a separate company. I'd love to redo Choplifter. What do you think?" So we began working closely at that point, which was just a year ago. It wasn't like we were sitting around drinking, going, "I want to do Choplifter."

This is really his baby. I mean, I was involved as a consultant, and in various capacities. And just to cheer people on, and give people the sense that we were really going in the right direction. But I don't want to take credit for the design -- I really didn't do that much work on it.

Do you have a piece of the IP? Where is the IP right now?

DG: That's a very complicated question, and I really don't want to say anything about it, because anything I say would be wrong. I will refer you to Brian for all such questions.

You said you were involved very early in the design of it. Were you just brought in to maintain the Choplifter vision? What did that entail?

DG: Yeah. I spent like three days, intensely with the team. They had already gone a ways along in trying to find what they wanted to do with this, and so I came in and they just laid it all out for me and I had my two, three, and four cents' worth of input. And we wrestled back and forth about some big picture things. I didn't say much about the little picture stuff. Yeah, I would say it was like a big picture rehashing of the details they'd come along with so far.

And then I've been in a couple times to just kind of look over their shoulder and go, "Yeah, yeah, that's what I was thinking. What do you think?" So it's just sort of like the grand old man influence, and, "Hey, what do you think?" I was never in charge of the project. I never had a leading role in it, oranything like that. Just a design consultant, really.

But we've got some kind of tie into the original vision, and I could help them maintain that. And it turns out there weren't a lot of things that I had to say that weren't exactly what they had in mind. Because I think they really got the original. They got what was really cool about the original, and they were really trying to maintain it in a 3D world.

Your name is on the title screen, even for the other versions of Choplifter that you weren't involved in.

DG: Yeah.

Have you ever been recognized by your name by people who aren't necessarily in the games industry?

DG: Well, yes. By players of games, definitely.

When you introduce yourself as Dan Gorlin, do people often go, "Oh, the Choplifter guy?"

DG: Twenty years ago, yes, they often did, and it was because they'd played the game. When you play the game, you can't help see my name over and over again. So it's the kind of thing where you're, "Dan Gorlin, Dan Gorlin... That sounds familiar. Why does that sound familiar?" So yeah, I got that a lot, early on.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like