Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Hint: It's all about the narrative, not just the puzzles, as writer Justin Bortnick explains while he shares some of his thoughts on ARG design and his work on the ARG campaign for Frog Fractions 2.

Last month, in preparation for the 2018 Game Developers conference, we were joined by writer and narrative designer Justin Bortnick on the Gamasutra Twitch channel so that we could discuss the practical realities of working on the Frog Fractions 2 ARG campaign.

(In case you weren't aware, Bortnick will be presenting a talk at GDC discussing the design and development of that ARG, which he worked on along with designers Erica Newman, Justin Melvin, and Micah Edwards.)

This is notable because, while alternate reality games have faded somewhat from the game marketing lexicon, the Frog Fractions 2 ARG was remarkably successful and deeply intertwined with the game itself. Frog Fractions 2's odd adventure game with ZZT-era graphics isn't just about killing monsters and unlocking items, it's about unlocking secrets inside of secrets inside stupid jokes, a game that spans the real world as well as the digital one.

Bortnick had a lot to say on the topic, and much of it will be of interest to any game devs thinking about how to design intriguing, attention-grabbing ARGs. We've embedded the full video of our conversation up above for your perusal, but below are some key highlights from Bortnick that may inform your game-making process, whether you're into solemn storytelling or telling the stupidest jokes you can think of.

Stream Participants

Bryant Francis, Editor at Gamasutra

Alex Wawro, Editor at Gamasutra

Justin Bortnick, Puzzle Designer at Twinbeard Studios, Writer & ARG designer for Frog Fractions 2

Bortnick: What do I think I left out about ARG design in general? I know this because I often have after work drinks, maybe once every one or two weeks, with Maureen McHugh, who is also here at USC with me and did the I Love Bees ARG for Halo, back years ago, and many others. If you want to talk to somebody about ARGs she's way better at this than I am.

"[The makers of I Love Bees ] didn't intend all ARGs to be puzzles, but that's just what it became. And they thought 'Oh okay, we'll make this thing be puzzles and they'll solve it, but the next thing won't necessarily need to be that.' But that's just what they are now."

But it's that every situation is just completely different. The rules of one ARG are not necessarily applicable, in terms of how to play or even what the design of it is going to be. She even told me, when they did I Love Bees. She also did Year Zero for Nine Inch Nails and that sort of stuff. But wen they did that and it was puzzles, they didn't intend all ARGs to be puzzles, but that's just what it became. And they thought "Oh okay, we'll make this thing be puzzles and they'll solve it, but the next thing won't necessarily need to be that." But that's just what they are now.

I think that I would have liked to see an ARG that's not primarily based on puzzles, but is equally compelling. I'm not sure if I can solve that problem.

Francis: That's an interesting thread to jump down though. Like, do you think an ARG needs to be anything other than a puzzle? Like, I Love Bees was probably my introduction into this, and then I spend a lot of time in the Bioshock 2 ARG. And it seems to be only puzzles, and then fragments of narrative, if there's one going on. By obviously those narratives are way more coherent than what Frog Fractions is, or at least palatable, I guess? That's not the right word either.

Bortnick: So Frog Fractions 2's ARG definitely had a definitive story, and the people that were with it, for most of it, can probably tell you, in the same way that somebody who's played a lot of Dark Souls is really sure about what the story was, and could tell you really coherently about how this and this and this happened in this order, and that's the story of Dark Souls.

That was actually something that Jim said to me when he gave his design intent, "Make it more like Dark Souls!" Just keep making it more like Dark Souls. Like, what does that mean?

Wawro: I find this whole topic fascinating, but we have to be careful how we talk around it, because I think an alternate reality game can be just anything, like any story, any weird subversion of your day-to-day life, in some sense that's a game in reality.

Bortnick: Right. I think that, if you take it to its most literal alternate reality game, the primary goal shouldn't be to present puzzles, but should be to present a compelling alternate reality; so I think that, if you have something that's just puzzles, and doesn't have a story that goes with it, that doesn't have this narrative hook, it's not an ARG, it's just a puzzle hunt. MIT does the MIT Mystery Hunt every year, and it's just, you solve a bunch of puzzles, and they're incredibly challenging for puzzle experts. But I don't think anyone's going to call the MIT Mystery Hunt an ARG.

Wawro: I totally agree. That reminds me, this is something I'm really fascinated by. When I was doing research for this years ago, I found a very early ARG, I think it might have been one of the first, it was in the early- or mid-nineties, the SF Chronicle put aside grant money for somebody, this guy created a website, a story that pretended to be real. It was updated every couple of days.

You could click through to find out what happening to this missing person case or something. And then they would go out and stage events in San Francisco. And people could just show up to these things, and these actors would set up these scenarios. There were no puzzles, it was just about creating this air of mystery, much like Majestic did a couple of years later. And so that is, I think, a fascinating era to explore.

Wawro: So that's really interesting, it makes a lot of sense and clear has worked really well in this case, but it is something that you are aware of. You don't know if it works for anyone but you, but you pitched this talk to GDC presumably because you think you're someone people should go to. Why do you think this kind of presentation is important to the game industry? I don't mean to ask, why is this so groundbreaking and important, but why did you think this was worth taking the time and effort to put together a proposal, and then writing and practicing that talk?

Bortnick: I think that the content of the talk is largely about what happened. Because I think that there was a real, just from speaking with other developers, being at GDC last year and other industry events, often the first question people ask is, "What happened with all that Frog Fractions 2 stuff?" I saw an article on Polygon or whatever, but what actually was it? And I had to talk around it for a long time because the game wasn't out. And even now that it is, that's a really long story, I can't just stand here for 45 minutes and tell you the entire history of the ARG.

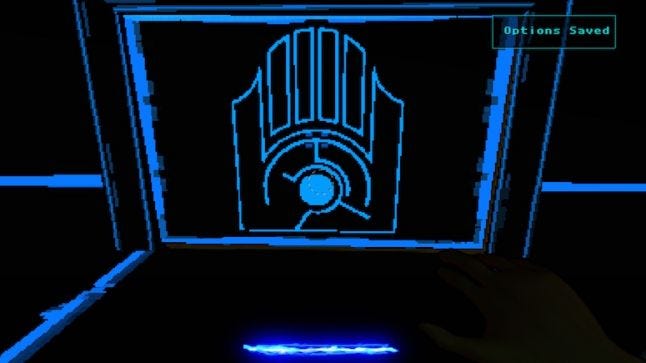

Bortnick worked alongside a team of people to run the ARG, including a number of devs who agreed to hide clues in their games -- like this one, hidden in Question's The Magic Circle

So I think that it was in part because I saw that there was a real desire, amongst people who work on games, to literally tell what actually happened, like basic stuff. What did you do? So that was a huge part of it.

"[Your] primary goal shouldn't be to present puzzles, but should be to present a compelling alternate reality; so I think that, if you have something that's just puzzles, and doesn't have a story that goes with it, that doesn't have this narrative hook, it's not an ARG, it's just a puzzle hunt."

The other part is, it's submitted as a business/marketing talk, in addition to a game design talk, and while I can't say everybody should do their design the way I do, where it just comes to you, because that's so personal and subjective, I can talk much more concretely about what worked in terms of the ARG as a marketing campaign, what didn't work, whether it was worth doing this sort of thing tailored to whatever your product is, for your game, whether I would do it again, that sort of thing.

So, it really straddles the design/marketing dichotomy. Because it was a game unto itself -- the ARG ended up being a game that was related to, but distinct from, the game you're playing on the screen right now.

Bortnick: Part of the problem with games is that, compared to books or film, which are two older and more established narrative forms, we understand where meaning in those forms is derived from. There's a really good GDC talk by Clint Hocking called "Dynamics: State-of-the-Art" where he talks about the Kuleshov Effect, and how, in film, meaning is derived through the cut. Cutting between two images transposes those images in a way the viewer is able to get some sort of meaning from their juxtaposition.

How does that happen in games? We understand how sight narrative works in some games, I feel like I can pretty safely say we've solved the text adventure, we understand how narrative happens in a text adventures, I don't think we've done that for every genre, and the more mechanically complex games get, the bigger that challenge is. So even the most mechanically complex film, in terms of the craft, is still the director pointing the camera at something. When, in a game, a lot of times the player is the camera person, or the director, or the builder in Minecraft; whatever the game is, it's much harder to point the camera at a specific thing.

When people were saying that ten years ago, what's the Citizen Kane of games, I don't think they were asking about which would be the game that legitimizes games as an art form, but what is the game that explains the medium to us as viewers as viewers, players and critics the way that Citizen Kane does, which gets the credit because nobody watches Birth of a Nation because it's super racist.

I think that's what they were looking for, right? If you were going to sit down and ask what is the Citizen Kane of games, it's because they were looking for something that gives the form meaning in a way that we can articulate.

For more developer interviews, editor roundtables, and gameplay commentary, be sure to follow the Gamasutra Twitch channel.

Gamasutra and GDC are sibling organizations under parent UBM Americas

You May Also Like