Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This paper tackles the research question: What did most people think about GamerGate? What were the biggest patterns in how people reacted to GamerGate, and how do they remember it, now that a year has passed?

This paper was originally posted on my blog Superheroes in Racecars.

Lately I’ve been troubled by the fact that GamerGate’s supporters and I seem to have completely opposite perceptions about what most people think of their movement. I’ve had GamerGaters tell me that most people don’t equate GamerGate with online harassment and that most people (or at least, most gamers) are actually on GamerGate’s side. How is it that our perceptions of “what most people think” are so different? Could it be that we all live inside some social-media echo chamber that makes us oblivious to other points of view?

So I decided to start a little research project to settle the question: What did most people think about GamerGate?

The results of this project suggest that the vast majority of people do in fact equate GamerGate with online harassment, sexism, and/or misogyny. More people see GamerGate as a toxic mob rather than a legitimate movement worthy of respect.

The following paper goes into great detail about how I conducted this research and why I reached those conclusions. This paper also reads like a historical analysis of the previous year by uncovering patterns in the ways that different people reacted to GamerGate.

There’s a strong TRIGGER WARNING for anyone who was deeply affected by last year’s events and similar forms of harassment. Things get particularly heavy in the section titled Patterns in How People Reacted to GamerGate.

There are several methodologies that one might consider when tackling this research question. Since the whole event produced a ton of discussion, most of which seems to have taken place online, I chose to focus on analyzing the tons of online content that were produced since the birth of GamerGate. However, since it is impossibly difficult to analyze all of that content (much less gather it), I inevitably had to decide how I was going to narrow things down into something more manageable. I also had to accept that not all of that content had equal weight to it. For instance, an obscure forum post almost definitely wouldn’t have had as much of an impact on “what most people think” as a popular and widely-distributed news article.

With that in mind, I chose to gather as much of the “popular stuff” that I could find about GamerGate. I reasoned that I would be able to get a pretty solid estimate of popular opinion by looking at the most significant artifacts that were produced by the public. I was also working off of the assumption that all of the smaller, more obscure leftovers wouldn’t end up making a significant difference to the results.

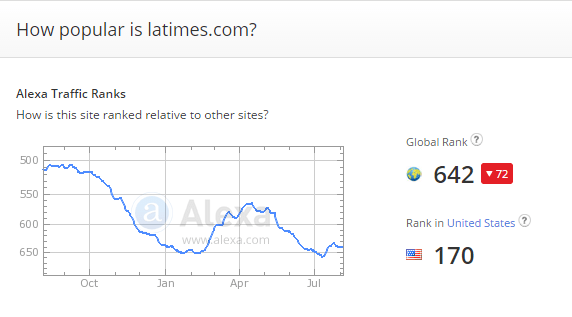

Measuring popularity is pretty difficult since we don’t really have precise data on all of the individual webpages across the Internet. Rather, I mostly worked off of Alexa.com‘s Global Rankings, which is an estimate of the relative popularity of websites across the internet. I chose not to consider Google search rankings when measuring popularity, because they’re significantly determined by relevance. For instance, just because a site might have the word GamerGate written all over it doesn’t mean that people actually go there.

Alexa Rankings fluctuate a lot.

The drawback to using Alexa rankings is that this metric isn’t useful for analyzing platforms such as Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Reddit, etc., and so I couldn’t directly analyze social media content with this approach. This isn’t to say that social media was entirely ignored. The most significant stuff inevitably bubbled up out of social media and into the essays, news articles, and wikis that covered GamerGate. It’s also worth noting that for many of these popular sites, a significant amount of their incoming traffic comes from social media.

My process for gathering the data sources revolved around finding websites and publications that covered GamerGate, and then for each website, I would gather every single thing that they published on the subject. This was done by using a mix of Google searches, in-site searches, and by following links between sources. I also visited certain websites directly, which was necessary in order to make sure that the most popular game publications were represented in the data, such as Gamespot, IGN, and others. Below is a rough summary of the rules that I used to determine whether or not to include a particular source in the data set:

The source had to be written in English.

It had to be from a website with an Alexa Global Ranking lower than 11,000. This number is essentially arbitrary, preferred over 10,000 so that I could include Gamasutra, since it’s perhaps the top game developer-focused publication.

The source had to be explicitly about GamerGate or significantly related to it. For a source to be “about GamerGate,” it had to satisfy at least one of the following criteria:

Is GamerGate the main subject of the source?

Does the source define or explain (however briefly) what GamerGate is? There were dozens and dozens of articles that simply made a single-line, passing reference to GamerGate, which were filtered out by this rule. However, if the writer took the time to define what GamerGate was, even if that definition was only one sentence, it suggests that GamerGate was significantly related enough to be worth the author’s time to describe it.

Did the publication explicitly tag this source as belonging to their GamerGate category of articles? This particular rule resulted in a lot of adjacent stories to be included in the data, especially stories about online harassment, Twitter, Intel, Wikipedia, and the Hugo Awards. This was perhaps the clearest way of assessing whether or not that publication thought something was “GamerGate related,” but not all publications had this form of categorization, hence the necessity of the previous rule.

Is this article about a topic that has been categorized as “about GamerGate” in several other publications? For instance, if 10 publications wrote about topic X and explicitly reported on its connections to GamerGate, then if Publication #11 doesn’t explicitly make that connection when reporting on topic X, I would still classify that source from Publication #11 to be “about GamerGate.” This rule was mainly added so that articles that were obviously GamerGate-related could be added to the data set without requiring such a thorough inspection.

I ignored obscure community content, unless it was actively signal-boosted by the publication. This allowed me to include things like featured community blogs and top comment responses.

If a source did not meet any of the previous criteria, but the source did include links to “Related Articles” that were mostly about GamerGate, then that would not be sufficient to be included in the data set. This was mainly due to the difficulty of distinguishing between links of actually related content and links to “other articles that were published that week.”

Because of the criteria that I used to collect sources, the data ended up being very biased towards what journalists, columnists and other writers thought about GamerGate. Given how unanimous the results were, however, it’s reasonable to think that popular opinion wasn’t very far off from the opinions that these writers were expressing. I’m essentially assuming that the world of journalism had more of an impact on “what most people think” about GamerGate than all of the YouTube videos, Reddit threads, and Twitter hashtags combined. There is a more thorough interrogation of this assumption in the Comparing Estimates of Population Size section of this paper.

This was not a comprehensive study. In fact, my decision for when to stop gathering data was fairly arbitrary: I stopped once it was getting hard to find new stuff to add. It’s likely that there are more English-speaking websites in Alexa’s top 11,000 sites that had covered GamerGate, but to do a comprehensive analysis of all of 11,000 of those websites would have been far beyond the scope of this little research project.

In total, I had collected 1,183 sources from 90 different publications. Click here to view the full data set.

Below I’ve listed the first 53 sources (about 4% of the data), so that you can get an idea of what the data looks like. The list of publications is ordered by their Alexa Global Ranking (as reported between August 1st and August 14th, 2015), and the sources underneath each publication are ordered chronologically.

Wikipedia — Alexa Ranking 7 — First result on Google. Explicitly defines GamerGate as an anti-feminist harassment campaign.

ABC News — Alexa Ranking 81 — Broadcasted a story critical of GamerGate harassment on national primetime television in the United States.

BBC News — Alexa Ranking 82 — Covered GamerGate horror stories through online articles, a video interview, and multiple segments on radio shows.

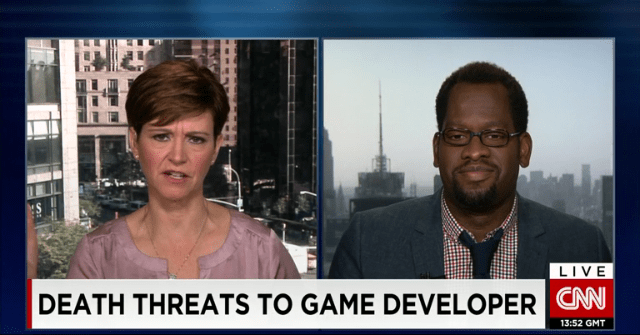

CNN — Alexa Ranking 88 — Broadcasted multiple stories about GamerGate on national television, also published multiple written reports, all depict the movement as a harassment campaign.

The Huffington Post — Alexa Ranking 107 — Hosted three roundtable discussions via webcast to amplify the more reasonable parts of GG. Also published several pieces that were highly critical of the movement and its harassment campaigns.

The New York Times — Alexa Ranking 112 — Wrote occasionally about GamerGate both online and in print, featured on the front page of an issue.

View the Full List of 1,183 Sources →

There are three degrees to which different publications in this data set supported GamerGate:

Consistent outspoken support: Breitbart was the only publication in the data set that published content that was consistently pro-GamerGate. Any other websites that heavily favored GamerGate were simply too obscure to fit the selection criteria. Compared to the other pro-GG sources gathered in this study, Breitbart‘s support of GamerGate was so much more radical and overt. Rather than reporting on GamerGate neutrally by covering all sides of the story, the publication instead posted dozens of tabloid-like reports against journalists, feminists, and other critics of GamerGate. Breitbart published 60 articles on this subject.

A GamerGate-friendly atmosphere: The Escapist was the only publication that fit this description. I interpreted their behavior during GamerGate as simply trying the give the movement the biggest benefit-of-the-doubt ever, while attempting to promote discussion and amplify GamerGate’s most reasonable voices. In other words, they treated GamerGate as a legitimate movement without officially taking sides. However, this proved to be a controversial stance, given how strongly many people believed that GamerGate was a hate group and that the Escapist was enabling that hate. The Escapist published 16 pieces on GamerGate, some of which directly criticized the movement and others which gave voice and legitimacy to the movement’s concerns.

The Outliers: There were three writers in the data set who published pro-GamerGate content while writing for publications that predominantly depicted GamerGate negatively. These writers were from Forbes, TechCrunch, and CinemaBlend, and they were each the sole GamerGate supporter on the writing teams for their respective publications. Their support for GamerGate was usually pretty reasonable and genuine, primarily focused on journalistic integrity and demanding more respect for gamers. They didn’t show anywhere near as much contempt for feminism as Breitbart did, for instance. However, their work was also surrounded by other writers who expressed sharp disapproval of GamerGate’s misogyny, and so their publications’ GamerGate coverage tended to be more critical than supportive.

And that’s it. Breitbart, the Escapist, and three random writers are all of the pro-GG voices that were high-profile enough to be included. Together they make about 3% of the publications cataloged for this study. Practically every other publication depicted GamerGate as being inseparable from online harassment and misogyny.

As I said in the Methodology section, one of my core assumptions is that the most visible coverage of GamerGate had a greater impact on “what most people think” than GamerGate’s social media presence did. Let’s take a look at some more metrics so that we can at least get a rough idea for how solid this assumption might be.

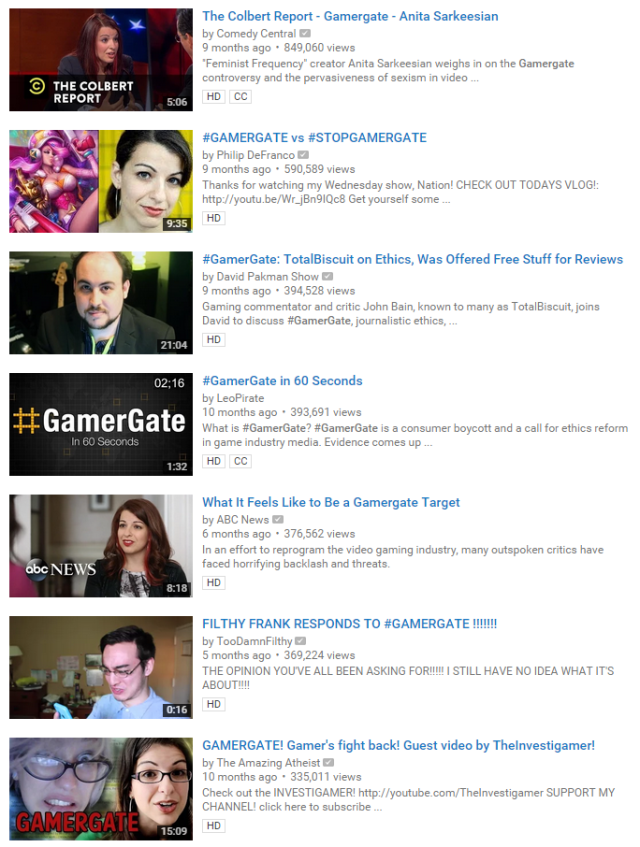

Since many of the GamerGaters I’ve spoken to cite YouTube as one of their main sources for pro-GamerGate coverage, I wanted to get a rough estimate of the audience that GamerGate videos tend to attract. So I did a YouTube search for “GamerGate” and ordered the results by views.

The top 7 most viewed videos on YouTube, when searching for “GamerGate”

I was really surprised by the results. I was expecting to stumble into a predominantly pro-GamerGate space, but the top results had quite a bit of anti-GamerGate content. In fact, the most-viewed GamerGate-related video on YouTube is outright mocking the movement for its sexism, and with 850K views, it has more than double the views of the top pro-GamerGate video. In second place is a video with 590K views from a popular “news show” channel, and while it tries to explain GamerGate without taking sides, it inevitably covers its links to online harassment and death threats. And finally in third place is a mostly pro-GamerGate interview with 390K views. However, when looking through the rest of the results, the top videos by GamerGate’s most prominent voices don’t usually have more than 300K views.

But what if the most-viewed pro-GamerGate videos didn’t have the word “gamergate” on them? I did a search for “Zoe Quinn” and looked for videos about her and gamergate topics, since she was supposedly GamerGate’s very first talking point. The top video had 280K views, the second had 200K views, and third place had 130K views.

The other popular GamerGate congregation point on the Internet is the subreddit KotakuInAction, which has almost 49K subscribers. There’s also 8chan, which reports having about 3K active users in its video games board, 2K in its politics board, and only 400 in its GamerGate board. If I had to combine all of these numbers into a single, rough estimate for how big GamerGate is, I’d give it the super generous estimate of 300K or 400K, mainly because of the top-viewed pro-GamerGate videos.

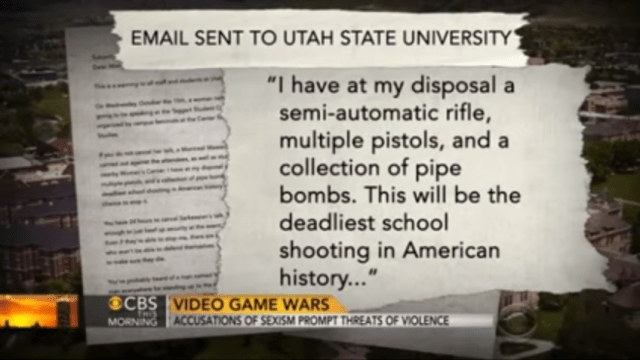

On the other hand, the Colbert Report is estimated to have reached 1.0 million viewers through television alone during the week of October 27 – 31, 2014. Nightline from ABC News was estimated to have reached 1.5 million viewers during the week of January 12– 16, 2015. CBS: This Morning was estimated to have reached 3.0 million viewers during the week of October 13 – 17, 2014. We could keep adding more ratings from the television and radio broadcasts from MSNBC, PBS, BBC, CTV, CNN, etc., followed by the cumulative audience for the print and online publications gathered in this study, but it’s already clear that my generous 400K estimate of GamerGate’s size won’t even compare.

Several cable news programs reported on GamerGate’s harassment campaigns.

Since GamerGate feels assured that most gamers agree with their cause, let’s compare this estimate to gamers specifically. Almost two years ago, Spil Games estimated that 1.2 billion people play video games. Since GamerGate was concerned with online journalism, we could instead focus on their estimate claiming that 700 million gamers play online games. But if that definition of “gamer” is too broad for you, we could instead reference the 70 million people who purchased Minecraft. Or if Minecraft isn’t hardcore enough, then perhaps we can compare our estimates to the 52 million people who bought Grand Theft Auto V. Regardless of which estimate you use to define who is a “gamer,” GamerGate’s size is still less than 1% of either of those populations. Given the sheer magnitude of gaming’s audience, it makes sense that mainstream media coverage would have a stronger impact on this audience’s opinion rather than GamerGate’s presence on social media, which is just obscure by comparison.

The low number of high-profile, pro-GamerGate stories found in this study is consistent with these estimates that suggest that GamerGate is an extremely small minority.

Let’s analyze what each publication’s first GamerGate-related article looked like. There were three main “entry points” through which different publications started covering GamerGate:

1. Intel and its Advertisements

There were a lot of tech and business publications that became interested in the story of Intel refusing to do business with Gamasutra due to complaints by an online movement. These publications don’t follow the games world closely enough to be aware of all of the “gamers are dead” drama, so when they researched what GamerGate was, they saw a backlash against those who criticize the most extremist parts of gamer culture.

Re/code’s piece “What Is Gamergate, and Why Is Intel So Afraid of It?” described GamerGate’s ethical concerns as “a front for a toxic smear campaign.” The Verge published a report titled “Intel buckles to anti-feminist campaign by pulling ads from gaming site,” and went on to cite the chat logs recorded by Zoe Quinn as evidence for the mob’s insincere interest in journalistic ethics. Engadget‘s report “Intel is ‘not taking sides,’ but keeps ads off of Gamasutra” defined GamerGate as “an internet campaign to hit gaming websites that speak out against sexism in the industry.” CNN‘s first report on GamerGate, titled “Intel pulls ads over sexism in video game drama,” identified that GamerGate was part of the same mid-August backlash that attacked Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn with “graphic threats of violence from defensive gamers and Internet trolls.”

2. What Exactly is All of this GamerGate Stuff?

Of course, GamerGate objected to being portrayed as an anti-feminist harassment mob, so they started making a lot of noise claiming that no one seemed to be taking the time to properly research their cause. This then encouraged more journalists to take a closer look at GamerGate, which lead to the next wave of articles that tried to explain the confusing ball of mess that was GamerGate’s origins and controversies. Many journalists spoke directly to GamerGaters via social media, invited them for interviews, and even had them appear on-camera thus challenging the stereotype that GamerGaters were all anonymous online trolls.

This led to a lot of “GamerGate explainer” articles, both from publications that had previously reported on GamerGate and from a few new ones as well. For instance, Vox‘s first GamerGate article was a super short piece claiming “The confusion around #GamerGate explained, in three short paragraphs,” which they then followed up with a much larger piece called “#GamerGate: Here’s why everybody in the video game world is fighting.” Gawker posted its widely-read piece “What Is Gamergate, and Why? An Explainer for Non-Geeks.” Meanwhile, Deadspin‘s “The Future Of The Culture Wars Is Here, And It’s Gamergate” was widely cited by other publications. The Verge uncovered so many allegations, dramas, and sub-controversies when researching GamerGate that they just dumped it all into an article called “What’s happening in Gamergate?” which showcases just how ridiculously complicated GamerGate is.

“At this point, a significant amount of Gamergate seems to be people fighting about things that have happened over the course of Gamergate.”

— Adi Robertson, Reporter at The Verge

Despite GamerGate’s claims that no one in the mainstream media bothered to research their movement properly, the data shows that there was actually a fairly widespread effort across several major publications to research and understand GamerGate. Even major publications such as those who work in cable news, which one would expect to be significantly out of touch with games and online culture, captured many of the details fairly accurately. However, even with all of this research, most of these journalists still concluded that GamerGate was associated with harassment and sexism. This in turn led to many GamerGaters responding to those articles with insults and vitriol (which is apparent in many of the comments left under most GamerGate articles).

This trend of almost all GamerGate explainer articles attracting negative reactions from the movement was so visible at the time that ClickHole published a parody article called “A Summary Of The Gamergate Movement That We Will Immediately Change If Any Of Its Members Find Any Details Objectionable.”

3. Harassment and Death Threats

In early September, there were a few publications who reported on the game industry’s viral petition to stand against the harassment campaigns and criminal death threats that led to Anita Sarkeesian and Zoe Quinn fleeing their homes in August. But then in mid-October, the same kind of death threats hit Brianna Wu, which led to headlines that said, “Another Woman In Gaming Flees Home Following Death Threats.” And then within the same week the headlines ran “Feminist video-games talk cancelled after massacre threat.”

CBS This Morning investigates GamerGate.

This week in mid October was GamerGate’s peak of awfulness. At this point in time, the story of GamerGate was spreading like wildfire to dozens of publications that hadn’t covered it yet, because when people heard that another mass shooting almost happened, it attracted a ton of attention. This is how most people first heard about GamerGate: as that online hate mob that sent all of those terrifying death threats to women in the games industry.

This was when the New York Times printed that front-page story about GamerGate, when Jezebel wrote “#Gamergate Trolls Aren’t Ethics Crusaders; They’re a Hate Group,” and when Vice published “Does Someone Have to Actually Die Before GamerGate Calms Down?” This was also when a lot of games/tech publications broke their silence on GamerGate because this was the wake-up-call that made them realize that this particular case of online harassment was much worse than expected.

1. Revulsion

“When ‘GamerGate’ rose up to cover over a campaign of harassment with a veneer of concern for the ethics of games journalism, it more or less set off every single disgust alarm I have.”

— Jeff Gerstmann, editor-in-chief of Giant Bomb

For most people, GamerGate seemed to get more disgusting the more they learned about it. They most likely heard about the terrifying death threats first, but then when they look into how GamerGate started, they see that it was an uproar over a potential conflict of interest for a review that didn’t exist for a game that wasn’t for sale. This is made worse by the fact that the original whistleblower for this ethical concern released his accusation in the middle of a gross, meticulously detailed, 9,400-word tirade in which he lashed out against his ex-girlfriend while broadcasting dozens of pages of dirty laundry. GamerGate couldn’t have found a less credible source to launch a movement off of.

To have such an overblown reaction to a claim that was so obviously a lie, that’s what made so many people conclude that misogyny must have been a key factor in the mob’s behavior. It got even more disturbing when Boston Magazine confirmed that the ex-boyfriend’s accusations were indeed part of a larger plot of revenge to cause “maximum pain and harm” to his ex-girlfriend. The whole situation is just absolutely disgusting, and the fact that there were people who sided with this jerk (who has no regret for what he did) is truly unsettling.

CNN anchor is visibly disgusted by GamerGate.

GamerGate’s ridiculous origin story was covered in detail in just about every GamerGate explainer article or news report, which served as a clear and widely-known example for the movement’s lack of legitimacy.

2. Fear and Terror

“I have gotten stuff this week that has scared the frak out of me, to the point that I’m having conversations with my husband about: what do we do if someone comes to our house? And I don’t know a single woman in the industry that is not terrified right now of being the target of this stuff.”— Brianna Wu on episode #18 of the Isometric Podcast.

As GamerGate seemed to jump to a new sub-controversey every few days, it became increasingly difficult to predict who was going to be labeled as the mob’s next target. Many female journalists who didn’t even have a remote connection to Zoe Quinn suddenly found themselves attacked:

“For example, someone recently and bafflingly tried to hack into my email and phone contacts. This is all very frightening to write, and so I must disclose that I am biased, insofar as I am terrified. I have worked in this industry for most of the last nine – not always perfect – years and I have never professed to be a perfect person. However, my values, my belief that abuse must not, cannot become “normal”, “acceptable” or “expected” is at odds with: oh, God, please, why are they doing this, what’s the point, don’t let it be me, don’t let it be me.”

— Jenn Frank, games critic at The Guardian.

Jenn Frank would later quit games journalism due to the increased attacks that she received for writing the above story.

“I have not said many public things about Gamer Gate. I have tried to leave it alone. . . Why have I remained mostly silent? Self-protection and fear.”

— Felicia Day, from her personal blog Felicia’s Melange.

When celebrity Felicia Day wrote about how scary the current environment was, she was immediately targeted and doxxed. When game developer Brianna Wu posted a few memes on Twitter making fun of GamerGate, that was enough to attract terrifyingly specific death threats. It was a consistent pattern of women saying, “I’m scared of GamerGate,” followed by a response from GamerGate saying, “Yeah, you should be scared!”

“Invariably, by speaking up [again], I’ll experience a new round of threats and harassment. The people doing this see themselves as noble warriors, not criminals.”

— Brianna Wu, from the Huffington Post.

These days, people mostly tend to remember the two or three highest-profile GamerGate victims, but the mob went after several other targets as well, ranging from mainstream journalists, to game developers, to random gamers on Twitter who spoke up against GamerGate, and even other GamerGaters who admitted to being transgender. The fact that they were going after so many people led to the widespread fear among many women in the games community that they would be next. It seemed as though just one miscalculated sentence or accidental fluke was enough to set the raging mob loose on you.

“Games were supposed to be a fun career choice. Now I’m afraid I’ll get murdered.”

— Anonymous, from Business Insider‘s coverage of the 2015 Games Developers Conference and its popular #1ReasonToBe panel.

There was also a significant amount of anxiety coming from the fact that the game industry’s overwhelming silence on GamerGate suggested that perhaps one’s own colleagues and bosses secretly supported the movement. The fear was that those closest to you might end up posting your information online and having the mob come after you next. It was a very reasonable fear to have, given that it’s exactly what happened to Zoe Quinn.

The hate was almost entirely aimed at women, confirming everyone’s initial interpretation that GamerGate was a misogynistic hate mob. Male voices wouldn’t attract anywhere near the same level of hatred:

“And that privilege is simple: I can say EXACTLY the same thing a female feminist does, in exactly the same arena, without having to change my address, fear for my personal data, or carry a rape whistle.”

David Trumble, reporter at the Huffington Post

(Footnote: Almost year after Jenn Frank quit writing about games, GamerGate eventually made her angry enough to want to come back.)

3. Sadness, Anger, and Outrage

It was depressing for the industry to see this kind of stuff happen to their friends and colleagues. It was depressing to see so much darkness coming from their own communities. GamerGate caused a lot of real damage to this industry: an immeasurable amount talent either left the field or chose not to enter it. Meanwhile to outsiders, the medium as a whole seemed to affirm its reputation as a hobby for losers.

“Video games are unquestionably poorer than they were two months ago when this strange and disheartening series of events began. Talented people are quitting. If this continues, the medium I love could go backward into its roots as a pastime for children. Instead of being a mainstream form of entertainment, it could end up being something like comic books, a medium that has never outgrown its reputation for power fantasies and is only very occasionally marked by transcendent work (“Maus,” or the books of Chris Ware) that demands that the rest of the culture pay attention to it.”

— Chris Suellentrop, games critic at the New York Times

Watching GamerGate during that time was like watching a fire rage across the games industry, destroying years worth of slow progress, as well as people’s lives. It was utterly heartbreaking.

The games community responded with a significant amount of anger against GamerGate. On the same day that Anita Sarkeesian cancelled her talk due to threats of a school shooting, the hashtag #StopGamerGate2014 started trending worldwide on Twitter, as thousands of gamers denounced and insulted GamerGate. During that month, writers started vocally calling for an end to GamerGate, in pieces such as The Verge‘s “Stop supporting Gamergate,” Metro News‘ “Online trolling and sorry excuses – why GamerGate needs to stop,” Bustle‘s “The “#Stop GamerGate 2014” Movement Has Been A Long Time Coming,” the LA Times‘ “It’s time to silence ‘gamergate,’ end the misogyny in gaming culture,” and many more.

Students at Utah State University protest GamerGate’s threats against their school. (AP Photo/Rick Bowner)

Former NFL star Chris Kluwe’s angry response to GamerGate “Why #Gamergaters Piss Me The F*** Off” was widely shared and cited by several publications, presumably because his article captured the community’s outrage against GamerGate.

“Unfortunately, all you #Gamergaters keep defending this puerile filth, and so the only conclusion to draw is the logical one: That you support those misogynistic cretins in all their mouthbreathing glory. That you support the harassment of women in the video game industry (and in general). That you support the idiotic stereotype of the “gamer” as a basement-dwelling sweatbeast that so many people have worked so hard to try and get rid of.

And you know what? That pisses me the fuck off. I’ve spent too long as a gamer, seen too much progress made, to let you tarnish that name.”

Chris Kluwe, at The Cauldron

4. Analyzing and Fighting GamerGate

Before October, the predominant expectation seemed to be that GamerGate would eventually die out like a passing storm. But as the months went by and as things got worse, publications started discussing theories for why it continued to rage on and how it might be stopped. Deadspin‘s “The Future Of The Culture Wars Is Here, And It’s Gamergate,” CNN‘s “Why #Gamergate won’t die,” and WIRED‘s Gamergate Goons Can Scream All They Want, But They Can’t Stop Progress suggest that GamerGate is just a microcosm for a larger struggle that’s happening across all entertainment media, where the widespread eradication of subtle sexism and the push for greater inclusiveness has been meeting significant resistance from people who feel threatened by this sea change:

“Even more fascinating is how these insecurities have allowed some gamers to consider themselves a downtrodden minority, despite their continued dominance of every meaningful sector of the games industry, from development to publishing to criticism. That demonstrates a strange and seemingly contradictory “overdog” phenomenon: The most powerful members of a culture often perceive an increase in social equality as a form of persecution.”

Laura Hudson, writer at WIRED

Boing Boing‘s “How imageboard culture shaped Gamergate” traced GamerGate’s strange behavior and bizarre beliefs back to the particular online subculture that dominates sites like 4chan, which has mostly avoided direct interaction with mainstream popular culture until now.

“The atmosphere [of imageboard communities] is that of a paradoxically jovial angry mob. Almost everyone sees their own point of view as the consensus, assuming that most people agree with them. Any possibly contentious statement is presumed to be ironic, told as a joke or to rile up people who disagree. Since everyone assumes that anyone who disagrees is arguing in bad faith and doesn’t mean what they’re saying, anyone who disagrees is a fair target for apparently hateful mockery.”

Jay Allen, writer at Boing Boing

The Guardian‘s opinion piece “Lazy coverage of Gamergate is only feeding this abusive campaign” argued that many publications have been giving GamerGate too much legitimacy by covering it as a debate with two sides when they should have been covering it as a disguised hate mob. RawStory‘s “#GamerGate is an attack on ethical journalism,” Vox‘s “Angry misogyny is now the primary face of #GamerGate,” and Salon‘s “Gamergate’s infuriating myth: Why searching for common ground is a big mistake” tried to convince more people to stop taking GamerGate’s flimsy ethical concerns seriously, with the hope that it would weaken the movement and end the hate.

Re/code‘s “The Gaming Industry Could Stop Gamergate — But It Won’t,” RawStory‘s “Don’t hold your breath waiting for major gaming companies to speak out against #GamerGate,” and the Daily Dot‘s “Only a culture of shame can finally put a stop to Gamergate” stressed the importance of actively denouncing GamerGate, because silence seemed to be enabling them. On the other hand, Forbes‘s “It’s Time For Video Game Journalists To Engage With #GamerGate“, Vice‘s “GamerGate Hate Affects Both Sides, So How About We End It?” and Slate‘s “How to End Gamergate” proposed the opposite strategy: that speaking with GamerGaters would be more effective than shunning them.

Others tried to turn the conversation towards improving law enforcement against GamerGate’s crimes, through articles such as The Atlantic‘s “What the Law Can (and Can’t) Do About Online Harassment.” A legal defense fund and a support/lobbying group were created by and for GamerGate victims. Twitter improved its harassment tools, helping with much of the process for filing police reports, while also improving its abuse response team. Some lawmakers started advocating for improved enforcement on criminal death threats, and the United States Congress held a briefing on how to stop online hate mobs like GamerGate.

5. Mockery

As soon as people became convinced that GamerGate was evil, many of them lost all respect for those who supported its cause. Many journalists would openly mock the movement, writing pieces such as the Mary Sue‘s “Today In Science: A “Gamergate” Is a Type Of Female Ant,” Vox‘s “The absurdity of the #Gamergate “ethics in journalism” argument, explained in memes,” and Buzzfeed‘s “14 Cats Having A Bad Day But Not Because Of GamerGate.”

The jokes and memes helped to delegitimize the movement, while also providing a good amount of catharsis to those who felt threatened and disturbed by GamerGate’s horrors. Many of GamerGate’s victims cited the anti-GamerGate memes as something that helped them keep their sanity, since it brought laughter into something that had been so overwhelmingly depressing.

Unfortunately, the increase of open hostility against GamerGate also brought a lot of ugliness to quite a few online spaces. Conversations about GamerGate, ethics, and social justice issues were now more likely to look like Chris Kluwe’s article: filled with angry, personal attacks against anyone who supports GamerGate. On one hand, it’s completely understandable that those hurt by the movement would regard its supporters with such contempt, but on the other hand, it also fueled GamerGate’s internal narrative that they were being systematically oppressed and harassed by feminists. GamerGate’s most visible supporters even received death threats of their own. There are too many people who think that GamerGate deserves whatever they get, but that mindset is eerily similar to what allowed GamerGate supporters to excuse their own movement’s harassment campaigns.

When you look at the data set holistically, Breitbart looks like an upside-down island in a sea of contradictions. Whereas virtually every journalist reported on GamerGate as a sexist, anti-feminist harassment campaign, Breitbart‘s first article on GamerGate, titled “Feminist Bullies Tearing the Video Game Industry Apart,” laid down most of the groundwork for what the movement’s supporters believed was reality:

That game journalists write too much about “politics” and social issues, and that the backlash to the “gamers are dead” articles confirmed that “everyone” hates those politics.

That it’s okay to make a big deal out of Zoe Quinn’s private life, because her supposed ethical crimes are true and therefore in “the public interest.”

That progressive games like Depression Quest don’t deserve the positive coverage that they’ve received, and must therefore have been part of a larger, ongoing corruption scandal.

That there is no evidence that the death threats against women in games are real or credible, and that they are most likely staged or exaggerated by feminists who want attention.

That the reason you don’t see more positive GamerGate coverage is because “the liberal tech establishment” is censoring those opinions.

Breitbart then went on to publish several pieces proclaiming that the games journalism industry was currently undergoing a “a death spiral entirely of its own making” presumably because such a high percentage of their readerships supported GamerGate. In early October, the Escapist contributed to this belief by publishing an interview with an obscure game developer who claimed that more than 75% of game developers support GamerGate, while dismissing the industry’s viral petition against GamerGate as being misleading. The Escapist also published an interview with an anonymous Microsoft employee called “Xbro” who claimed that over 95% of his studio, and the rest of the AAA industry, are secretly on GamerGate’s side.

First of all, I work at Microsoft. I can’t speak for the entire company, but there’s no way that number is anywhere close to true. Let’s look at the things that Microsoft has done in 2015 so far: we’ve published a website on the company’s stance on improving diversity, hosted a series of internal diversity research lectures, developed an expertly-made and well-researched training course on unconscious bias as part of the mandatory employee training, and ran a company-wide campaign called //HackForHer during this summer’s internal Hackathon to encourage employees to create projects that have women as their target demographic. And that’s not even mentioning the priority that our CEO has placed on these issues, which were announced during GamerGate’s peak of awfulness. Again, I can’t speak for the entire company (Microsoft hasn’t released an official statement on GamerGate), but the company’s behavior is certainly consistent with anti-GamerGate values. Furthermore, I’m not the only Microsoft employee who has disputed Xbro’s claims about the company.

In late October, when the Internet’s anti-GamerGate sentiments were at their loudest, Breitbart published a piece called “Incredibly, GamerGate Is Winning – But You Won’t Read that Anywhere In the Terrified Liberal Media,” where they cited multiple secret sources that claimed that pro-GamerGate opinions “are becoming commonplace” in the games and tech industries. In their piece, “The Authoritarian Left Was on Course to Win the Culture Wars… then Along Came #GamerGate,” they tell a story about how GamerGate’s success has been perhaps the most significant contribution to the decades-long “culture wars against guilt-mongerers, nannies, authoritarians and far-Left agitators.” As recently as last May, Breitbart published “Veteran Game Designer Denis Dyack: ‘Most of the Developers I Know’ Are Pro-GamerGate,” in which they continued to assure GamerGaters that everyone agrees with them.

This year I attended the 2015 Game Developers Conference, which is the largest games industry gathering in the world, and the atmosphere there was incredibly anti-GamerGate. Some of the panels this year included:

“Increasing Gender Diversity in Game Development Programs”

“Managing Game Communities Within the Culture Wars”

“Animation Bootcamp: Women Are Not Too Hard to Animate”

“Socially Responsible Game Education”

“Turning the Tide: Hiring and Retaining Women in the Games Industry”

“Curiosity, Courage and Camouflage: Revealing the Gaming Habits of Teen Girls”

“Game Developer Harassment: How to Get Through” (this panel received “resounding applause.”)

“Creating Safe Spaces at Game Events”

“Diversity Advocacy Workshop”

“Anti-Social Behavior in Games: How Can Game Design Help?”

“We Suck at Inclusivity: How Language Creates the largest Invisible Minority in Games”

“Women in Game Audio”

“Player Choice of Gender and Body Type in Sunset Overdrive“

My source for the above list was my copy of the conference schedule.

The GDC Awards are perhaps the single most-attended session of the conference, and when Nathan Vella denounced GamerGate on stage, the audience gave him a standing ovation that seemed to last an entire minute.

“And just like that, thousands of people are on their feet, clapping and cheering. In the crowded convention hall, it’s deafening. Vella’s speech isn’t exactly revolutionary, but it’s hard not to feel a little overwhelmed by the response. It’s an astounding moment.”

Nathan Grayson, reporter at Kotaku

Later in the same show, Tim Schafer famously mocked GamerGate using a literal sock-puppet, causing quite a bit of laughter from the crowd.

More proof that I was there.

Gamasutra, the most popular industry-facing news publication, didn’t publish or promote a single pro-GamerGate story or community blog post. There is literally no evidence that a significant percentage of game developers support GamerGate, other than whispers from random people claiming otherwise. Despite GamerGate’s extreme distaste for cherry-picked information, their perception of what we think of them relies heavily on some pretty weak cherries.

There were several “New Year’s” articles that looked back at 2014 as being the year when a lot of people realized that misogyny was a thing, thanks to GamerGate. The following articles all cite GamerGate as something that is being remembered not for its advancements in ethical journalism but for the misogynistic harassment campaigns that it was widely known for:

Metro News: “2014: Video gaming’s worst year ever,”

Polygon: “2014 in review: the year that sucked,”

Jezebel: “Fuck This Entire Garbage Year, TBH,”

The Daily Dot: “Why 2014 was actually a positive year for women in tech,”

Even the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Journalism Ethics weighed in on how unhelpful GamerGate has been to their field:

“In that, I see an inescapable link to this year’s most troubling ethics case: GamerGate. While many claimed this movement was about calling out ethical lapses in videogame journalism, I was astounded and appalled by the misogynistic and threatening nature of some posts. People — particularly women — were attacked for speaking out, often getting “doxxed” (slang for having your personal information documented or published online).”

Kathleen Bartzen Culver, Assistant Professor and Associate Director at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Journalism Ethics

PC Gamer‘s feature “The PC gaming lows of the year” starts with an open plea from their deputy editor trying to get through to whatever GamerGaters are still left in the movement. Polygon also published “The year of GamerGate: The worst of gaming culture gets a movement,” in which they mention that the popular games forum NeoGAF voted GamerGate as its 2014 Fail of the Year.

When I was gathering data for this study, I noticed that several publications seemed to be using their “GamerGate” category as a dumping ground for stories about online harassment, twitter harassment, or misogyny in general. This is why there were so many harassment-related stories included in the data set. As I mentioned in the Methodology section, I chose not to include several articles because they only had one-line passing references to GamerGate. For those articles, the vast majority of them were referencing GamerGate as a well-understood example of harassment campaigns or misogyny. They would often say something along the lines of “this is just like GamerGate” when trying to explain things such as the harassment of Reddit’s CEO Ellen Pao or the ballot-stuffing that happened at the Hugo Awards.

It should be clear by now that an overwhelming majority of people see GamerGate as nothing more than a misogynistic harassment campaign. While GamerGate might tell themselves that everyone’s been brainwashed by lies or something, they absolutely cannot avoid the reality that almost no one is on their side. No one takes them seriously, and pretty much everyone wants their hopeless movement to disperse already.

GamerGate might point to AirPlay as an example of journalists taking GamerGate seriously, but that effort seems to be born largely out of ignorance, from journalists who are far enough removed from tech coverage that they somehow missed all of the GamerGate stories last fall. Watching AirPlay’s organizer slowly get more fed up with GamerGate is like watching a microcosm of how everyone eventually gave up on trying to talk to GamerGaters.

“Maybe I should’ve listened to my fellow SPJ board members: This isn’t worth the time and aggravation, especially when compelling projects await. Maybe everyone else was right and I was wrong. I have no regrets, because I’ve learned so much and enjoyed almost all of it. But I’m beginning to regret wasting the time of so many others, lobbying them that GamerGate is worth a good, hard look.”

Michael Koretzky, SPJ Region 3 Director and organizer of AirPlay.

The Week compared GamerGate to a soccer team that has only ever managed to score on its own goal and responds with self-congratulatory remarks on a job well done. Their efforts to silence feminist and political critique of games actually ended up inspiring more of it. Their efforts to convince journalists to stop critiquing gamers for their sexist, bigoted behavior has only amplified people’s awareness of society’s misogyny problem. Their efforts to discredit Zoe Quinn, Leigh Alexander, Anita Sarkeesian, and Brianna Wu have led to them becoming some of the most respected voices in games, as more people are inspired by their work against abuse and their advancement of the medium itself. Their efforts to scare women out of the games industry actually led to more money, time, and talent being dedicated towards fixing tech’s diversity problem.

Before GamerGate, people might have had a rough idea of how diversity in teams was good for companies and how online harassment was maybe a problem that needed to be fixed. But now I suspect that people’s thought processes tend to go like this: Why do we need diversity in tech? Because of GamerGate. Why do need to fix online harassment? Because of GamerGate. Why is feminism so important? Because: GamerGate.

GamerGate was one of those landscape-changing events that deeply changed the communities affected by it. The entire tech industry seems to be much more aware of these issues, and supporting under-represented groups seems to be the “cool” thing to do now if you’re a tech or entertainment company. There’s still a ton of work that needs to be done before the problem of online harassment and misogyny is fixed, but for now, I’m just immensely proud to be part of an industry that’s moving in the right direction.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like