Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A look into how In-game item systems can increase player motivations by providing rewards, of both internal and external value; from virtual weapons, skins and keys.

This was initially drafted in January 2016 and used for coursework.

A product being used continuously in a set manner is subject to routine, a user of the product can be influenced into this manner by how the product sells itself. The establishment of routine is focused upon in the book ‘Hooked: A Guide to Building Habit-Forming Products’ by Nir Eyal.

It theorises a 4 stage framework in the process of how users become ‘hooked’ to the product they own.

The first stage is the trigger, this can be considered as the factor which sparks the interest to people and will actuate their behaviour. Triggers come in 2 types, external and internal; “When a product becomes tightly coupled with a thought, an emotion, or a pre-existing routine, it leverages an internal trigger. Unlike external triggers, which use sensory stimuli like a morning alarm clock or giant “login now” button, you can’t see, touch, or hear an internal trigger” (Eyal, 2013, P.41).

Team Fortress 2 (Valve, 2007) is an FPS multiplayer game released by Valve for the PC platform consisting of 9 different character classes to play matches in a team orientated style. Technically, wanting to play a game can be a trigger, but that’s quite broad to say, how can games further entice players?

TF2 had a set of achievements per each class to attract players to try each of them and learn through these milestones to understand how the class should be utilised. This can be considered learning through habits or attribution, for this instance an act of remembering being rewarded for doing the correct thing – positive reinforcement. Learning through reinforcement is known as Operant Conditioning, a form Behaviourism , where players can be encouraged or discouraged with their actions by being given positive or negative reinforcements and learning from it.

But when the achievements are completed, what would keep people wanting to continue?

One of the first developments was to reward players specific weapons when a certain amount of achievements were completed per class, but once players had done so they again had no other enticing features to keep them coming back.

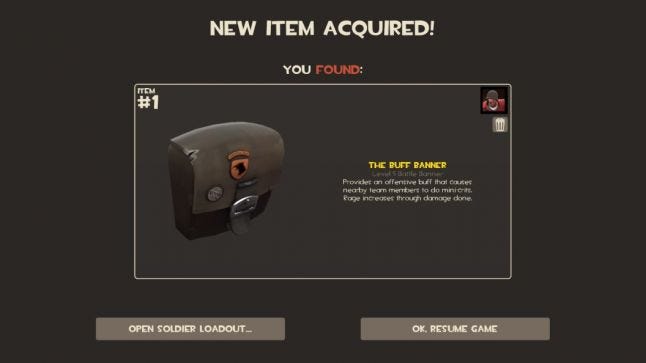

Valve decided to introduce a ‘Skinner box’ format to induce people to keep coming back to the game, the notable change came to TF2 and has greatly affected the player base ever since; an item drop system. People who would play the game for a certain amount of time would receive items at random intervals, consisting of either a weapon or cosmetics, this design choice would prove to give players a reason to play at least a few hours a week (the cap to how many drops resets weekly) because they were being rewarded for playing the game.

A skinner box is basically; rewards being given to subjects who perform a certain action (the reinforcer) to ensure specific responses are learned from a stimulus response association, this was discovered by B.F. Skinner after experimenting with rats and pigeons.

“Experimenting with different regimens of reward, he found that they produced markedly different patterns of response. From this was born a new area of psychology and one that has some strong implications for game design” (Hopson, 2001).

Players were not just being reinforced with rewards or punishments for their actions in-game like any game, but given actual items/equipment through reward schedules which could be traded with other players. This developed into an in-game economy where weapons found could be converted into metal and be used to craft cosmetic apparel or traded for Mann.co keys with other players. The keys represented real world value as they cannot be found, only bought and are supposed to be used opening crates, another item which could be found with cosmetics of different qualities when opened. This relates to the hook systems second phase, “Following the trigger comes the action: the behaviour done in anticipation of a reward” (Eyal, 2013, P.7).

The item drop system can be seen as a secondary reinforcer and the way the system is laid out creates a reinforcement loop: Cue>Behaviour>Reward, which is comparative to Nir Eyal’s hooked system. Players know that by playing the game they will be rewarded with items at random intervals of time until the limit is met per week. The conditioning to keep it random suggests it would be more effective for player engagement, most likely to prevent oversaturation of the reward. Desire and motivation drives people to continue playing, “What distinguishes the hook model from a plain vanilla feedback loop is the Hook’s ability to create a craving. Feedback loops are all around us, but predictable ones don’t create desire” (Eyal, 2013, P.8).

Money is the external factor that fuels TF2’s economy, a secondary reinforcer that started with Valve introducing the ‘Mann-conomy Update’. Released in September 2010, it brought in many new weapons, cosmetics, crate drops and the ‘Mann co. Store’ for micro transactions.

Players enjoy investing time into games to improve their ability in playing them, to either win more or simply enjoy the game further with competitiveness. But for others they prefer to customize their characters and ‘show off’ or simply want to profit from the financial side of investment with the in-game economy.

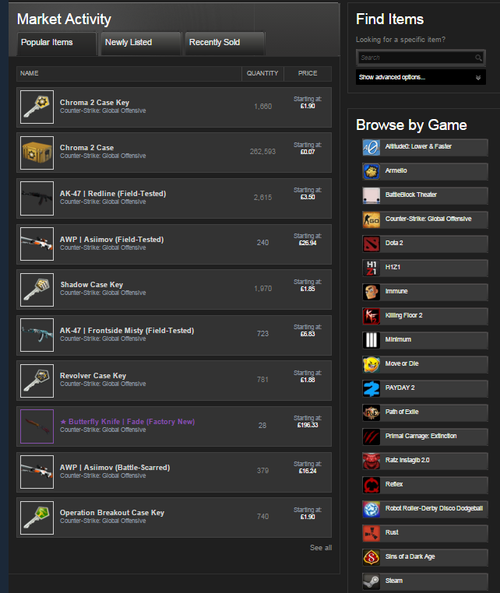

The extrinsic factors further progressed when on December 2012 Valve launched the Steam Community Market. After the success of Steam trading, Valve included the virtual market to allow users to buy and sell in-game items with Steam Wallet (funds on a Steam account). Now instead of exchanging items, players could earn currency which could be used to purchase whatever was available on steam from games, game expansions and other in-game item content.

The Steam community market itself had evolved into a tool for enticement, a way to keep players to remain ‘hooked’ and keep TF2’s economies more accessible and active.

This market is the pinnacle to the extrinsic form of investment, a player could collect their items and trade for items that could be sold on the community market and with acquired steam wallet funds they could buy items from other games or actual games.

Pictured above, the market in 2012. (Extremetech, 2012) |

“The last phase of the hook model is where the user does a bit of work. The investment phase increases the odds that the user will make another pass through the hook cycle in the future. The investment occurs when the user puts some-thing into the product of service such as time, data, effort, social capital or money” (Eyal, 2013, P.10).

With these two different versions of investment explained, it is clear that those who enjoy investing their time actually playing the game to improve for success with achievements and player skill are motivated by intrinsic factors. In comparison, investment into the rewards, cosmetics and monetary value is an extrinsic factor that motivates people to play the market over the actual game itself.

Team Fortress 2, as evidenced with Nir Eyal’s hook model, possesses both intrinsic and extrinsic factors of motivation with triggers, actions, rewards and investments. This has contributed it to become one of the most successful and popular PC games.

In relation to the changes in TF2, just before Valve’s release of the Steam community market, they had released the newest instalment of the popular Counter-Strike franchise – Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (Valve, 2012) in August 2012.

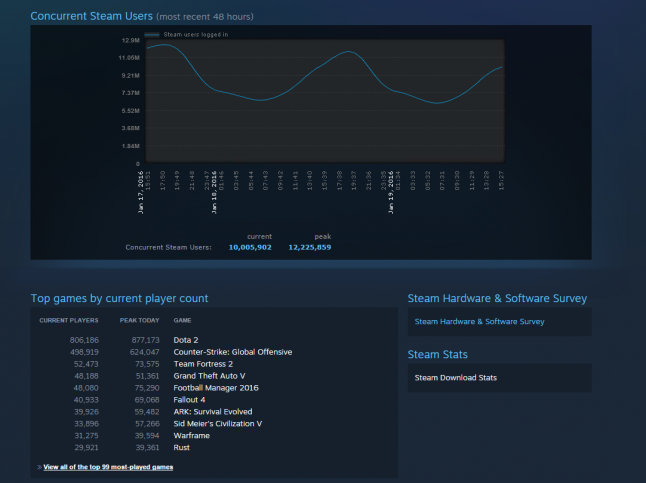

The game started off peaking with 50,000 individual players (Steamcharts, 2012), which even today is considered a fairly good active community. However, after a while the average player count started to drop and this of course was a problem for Valve who had invested money into the game, especially when the predecessors of the series, Counter-Strike (Valve, 2000) and Counter-Strike: Source (Valve, 2004) , were getting better peak player counts (Steamcharts, 2012).

Valve initially attempted a community map pack, based around a map pack from the steam community workshop to increase community involvement – with the most favoured maps being selected. ‘Operation Payback’ was CS: GO’s first paid expansion that released for a limited time between April 2013 - August 2013, with a percentage of the proceeds went to the map creators.

This update managed to increase the player base but only as a short term solution; however Valve wanted to continue the operation format and continue with limited series of community created content.

However, the main arose during the summer of 2013, collected data showed that the original Counter-strike had 35-40 thousand peak individual players, Counter Strike: Source had 25-30 thousand and CS:GO had 25-30 thousand. People’s general opinion was that they had little to no reason to change or play the newest game when they spent years learning how to master the previous versions of Counter-Strike. Regardless if professional teams had moved onto playing CS: GO, for the casual player there was no reason to invest time in a newer one with better visuals.

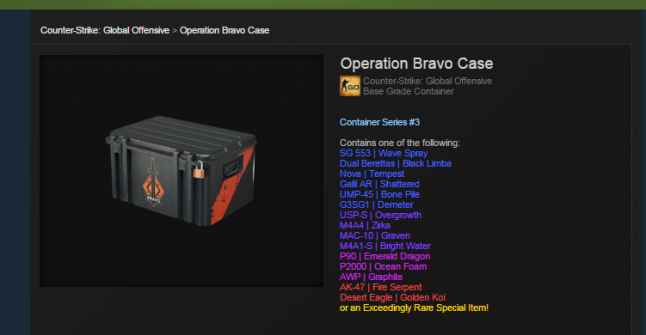

So Valve made a very important change, on August 14th 2013 an update called the ‘Arms deal’ update was introduced, an overhaul which would implement an in-game item inventory and item drop system. At the time this was initially joked about by the player base, in that Valve was making CS: GO more like TF2. This was plausible to think with the Item inventory and item drop system that was previously started in TF2, although for CS: GO it was set to be purely cosmetic to prevent balancing issues with guns. The guns of CS: GO would have decorated weapon skins which was sorted in a graded system, certain skins and cases could be earned by either simply playing the game (with a weekly reset format), trading, purchase through the steam community market or by opening cases through the games own ‘crate and key’ micro transaction system.

Yet again Valve was using behavioural design but this time to entice people to play the actual game rather than just to keep them playing it, of course with the new economy thanks to the release of gun skins, cases and stattrak weapons (Weapons with a kill count feature).

They clearly knew what they were doing, to quote Valve themselves “The Arms Deal Update is aimed at rewarding the wide spectrum of players who have already purchased CS: GO -- from players looking for new ways to express themselves in-game, to CS: GO’s competitive community getting well-deserved visibility and bigger rewards for their high level of skill.”

To be brief, most people who play games will play for enjoyment and its competitiveness, but there can always be those who need a little influence to be intrigued with the product (extrinsic factors).

CS: GO appeared to have had its issues solved by inserting external motivators, leading to players of the franchise returning to try it out again which increased numbers. Most players from competitive to casual liked the appeal of the gun skins to ‘show off’ their investment, a sense of bragging rights, which improved the games young in-game economy and interested others to take part.

Then there is the player like me who thought they could profit from it whilst enjoying the game, to play the game every now and then and be rewarded enough to pay off what I paid for by selling the skins for money on the community market, completely under the Skinner box’s influence.

Next came the 2nd operation, Operation Bravo, where only people who bought the pass had access to a new set of maps for casual play and now competitive as well, but now there was the offer of a special case and skin drops only available to those who had access. Now the operation is being used as an add-on to the Skinner box element of the item drop system, the strategy to pay money in quickly to earn the skins and cases quickly to potentially make a good profit by selling cases and skins as soon as possible on the community market.

If CS: GO had purely relied on its intrinsic factors, it may have never been as successful as it had become, because you can clearly see a change of player counter average and peak since August 2013 and the interest in the games professional tournaments.

With use of rewards through gameplay, players would be more captivated to play TF2 and CS: GO compared to other available FPS games thanks to the item drop system, or rather the anticipation of a good reward. It appears that a contributing factor for increased player counts and game life came from the implemented behavioural design choices to intrigue gamers and motivate them, thanks to the influence and conditioning of a Skinner box method. This leads to players actively choosing to play for the available variable rewards and triggered them to play these games instead of others in the first place.

However this design implementation didn’t always bring positive results, when TF2 developed an economy there was a surge in idle botting. People created accounts to simply remain idle in TF2 matches and use programs to keep doing this to receive item drops on several accounts; the focus was to gain items for monetary gain and affected people who wanted to actually play the game. With bots filling up servers, matches would become unbalanced and people who intended to actually play the game would become annoyed or bored, Valve then made a patch to attempt to prevent this and also made bans.

With the economies in TF2 and CS: GO came scammers, phishers and hackers who would prey on vulnerable people to get to their valuable items. Over the years the issue has gotten worse leading Valve into making many forms of account and trade protection that can be seen as quite absurd, from email verifications to mobile authenticators for each individual trade or market listing.

There are also the issues with gambling, which has proved more prominent with CS: GO with many gambling websites appearing during the games surge into popularity and wealth.

There are many players, young and old, who don’t fully realise the value of the items they possess and are susceptible to use their items of value to bet on professional matchups or simply in virtual games of chance. The biggest cause for concern is that there isn’t much prevention of underage players from taking part – simply having a steam account to connect through the web is all it takes.

Not too many players will realise using skins from a game to bet can have an effect on them, possibly developing into gambling addictions and start spending more money than they intended.

When looking at the system put in both games, the design choices it contains can be considered as unethical. In 1973 a study took place with conditioning humans, the subjects were children who were set to draw pictures, an activity they already enjoyed doing. They were split into 3 groups, one being promised a reward after drawing pictures, another was given a surprise reward after drawing pictures and the other group was not promised or given a reward.

Lepper and Nisbett’s experiment had revealed that all the groups of children initially had intrinsic motivation, they enjoyed drawing, but when two of the groups received the promised rewards their behaviour changed. The next phase occurred with the children continuing the same task, but this time without any extrinsic rewards, what developed was the children in the promised reward group had lesser interest in drawing now that the extrinsic motivator was no longer confirmed.

“The present results indicate that it is possible to produce an overjustification effect. In the expected-award condition, children showed decreased interest in the drawing activity after having undertaken it in order to obtain a goal which was extrinsic to the pleasures and satisfaction of drawing in its own right” (Lepper, M. Nesbitt, R. 1973)

However, with the other groups they maintained their interest, notably the group who received a reward unexpectedly, which represents a variable reward schedule. This conditioned the children to relate their behaviour to the enjoyment of the activity. This is how the conditioning of humans can be abused, notably gambling will provide the same motivators but can lead to addiction and badly affect them.

To finalize, conditioning with rewards schedules and attribution should be kept in moderation, people can become hooked in the endless reinforcement loop to earn rewards. This can lead towards addiction and discouragement if players become oversaturated with their expectations of the rewards and possibly give up the game altogether.

TF2 and CS:GO inhibits a well maintained variable rewards system that has developed overtime, proving to keep the game successful for over 8 years with its intrinsic and extrinsic motivators and investments.

I would like to finish with some anecdotes from my personal experience in looking at the steam platform which evolved from being a simple program to maintain Valve games into a small game distribution service into a massive multimedia community platform with its marketplace catered to in-game economies.

People like me are attracted to the fact I can play enjoyable games to earn financial rewards from either the in the form items from the games, trading items with other people or buying and selling on the community marketplace. As a personal experience on December 2014 I put in £40 into my account in preparation for the 2014 winter sale, but what happened is I took my first steps into community trading and from there I was hooked.

I spent most of my time in 2015 ‘playing the market’ instead of games because I am a clear example of a person enjoys rewards and will take actions to do so. The key selling points for me to play TF2 and CS: GO was the ability to earn back what I paid and profit from there, I started playing both of them in late 2014 and still find them enjoyable to play.

The DLC updates that started in CS: GO and also developed into TF2 definitely brought a sense of freshness to each game, I myself purchased them as soon as possible to get the rewards as fast as I can to gain maximum profit and generally earn back more than I put in each time.

For instance during the release of Operation Bloodhound in CS: GO, I paid £4 for the pass and in the first week I received 3 bloodhound cases and sold them altogether for just over £4, from there everything earned was profit and that’s what motivated me to play.

I am the perfect example of a player who was influenced by the conditioning set by Valve, they gain money from me by taking part and earn more money from the taxing the items I sell on the community market.

The in-game item system has proven to be so successful that other developers have taken notice and incorporated the system for their own games, as seen in the picture below (taken from the community market of today - January 2016).

Throughout 2015 I was buying, trading, selling, earning and profiting – and throughout the year I must have spent around £300 on games and expansion that initially came from the £40.

As of January 2016, I have made over 1500 trades and over 7500 market transactions, I’m involved with the community much more so than the actual games because I’m after the external rewards. In fact I have so much money invested in various assets and I still have £50, I haven’t added any more steam wallet codes, I didn’t need to, it all came from that original £40 code from December 2014.

With all its features, there isn’t any other PC platform that can reasonably compete with Steam; some may try to under-price their sale of games compared to it but they can’t compete with Steam’s growing community and market.

It doesn’t seem like any other platform can rival the external rewarding which Steam provides, unless by copying it.

Counter-Strike. (2012). Retrieved from Steamcharts website:

Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. (2012). Retrieved from Steamcharts website: http://steamcharts.com/app/730

Counter-Strike: Source. (2012). Retrieved from Steamcharts website:

http://steamcharts.com/app/240

Eyal.N (2013) Hooked: A Guide to Building Habit-Forming Products. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Hopson.J. (2001). Behavioral Game Design. Retrieved from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3085/behavioral_game_design.php?page=1

Lepper, M., & Nesbitt, R. (1973).Undermining Children's Intrinsic Interest with Extrinsic. Reward: A Test of the “Overjustification” Hypothesis (unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Michigan, Michigan. Retrieved from http://courses.umass.edu/psyc360/lepper%20greene%20nisbett.pdf

Operation Bravo case (2016). Retrieved from

http://steamcommunity.com/market/listings/730/Operation%20Bravo%20Case

Plafke,J.(2012, December) Valve’s Steam Community Market could change how we pay for – and play – video game. ExtremeTech. Retrieved from

Valve (2000). Counter-Strike [Video Game]. Bellevue, Washington: Valve

Valve (2007). Counter-Strike: Global Offensive [Video Game]. Bellevue, Washington: Valve

Valve (2004). Counter-Strike: Source [Video Game]. Bellevue, Washington: Valve

Valve (2007). Team Fortress 2 [Video Game]. Bellevue, Washington: Valve

Valve. (2013).The Arms Deal Update, Retrieved from

http://blog.counter-strike.net/index.php/2013/08/7425/

Valve. (2016).Steam Community Marketplace, Retrieved from

http://steamcommunity.com/market/

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like