Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How do you build a successful game business from scratch? In the first part of a high-level feature series, veteran exec Merripen, formerly of Cyberlore and Cryptic Studios, explains why the best game companies "...encourage their business side to flourish with the same creativity and passion seen in their games."

Common perception is that designing a game is glamorous but running business is robotic, inherently unethical and soul numbing. Common perception is wrong. Successful companies encourage their business side to flourish with the same creativity and passion seen in their games.

This is the first in a series of articles outlining the steps to build a successful game business. These steps provide business guidance for companies either at start-up or in transition. Though aimed at management, they encompass basic business principals that informed developers at all levels need to understand so they can make the best decisions for a company.

The game industry has a higher than normal set of the right people in the wrong places. Creative people start game studios, often just out of college. While possessing a great deal of enthusiasm and talent, they rarely share the same desire for negotiation, operations, finance, management or operations. Often people at the top get shoved into roles they don’t want to do, or aren’t suited to do. In startups, the CEO is often the lead “something” at a company �– a person with passion for designing, programming or art. This person is the idea or money person, though rarely is it someone who loves business. Business becomes the expedient for the expression of the creative side.

While a romantic, it’s a disastrous notion and an early death knell for a company. The CEO, corporate board and top executives must have the same passion for business as the devs have for games.

Take the CEO who would be far happier and the company better off as the company's Chief Strategy, or Creative Officer. Everyone knows at least one CTO, a position fundamentally about people, resource management and dollars and cents, who should be Chief Engine Architect, fundamentally about the code and design.

Boards are filled with founders, and don’t often draw on a vast pool of experience that exists outside the company. So they end up as giant rubber stamps or petulant micromanagers.

Studio executives are at best undereducated (at worst uninterested) in the operations, management or finance. Thus advice centers on immediate departmental needs rather than a holistic view of the company.

The top roles in game development and business design are very similar. Every game has a designer, publisher and leads. The designer is the visionary who can close their eyes and see the game. The publisher provides the resources to get the game out the door and a high level quality control. The leads are specialists guiding the people and process. Companies have parallel roles. The CEO equates to the designer, the publisher is the board of directors, and the leads are executives.

So the first step in creating a successful business is to make sure a company has the right roles and that they are filled with the right people.

A CEO should adore the fine art of business, be passionate about their craft, living and breathing strategy, leadership, negotiation, finance, operations and management.

The best game designers adore playing a game of Risk for the 100 millionth time because see some new nuance of the rules they may be able to use. The best CEOs thumb their dog eared copy of The Definitive Drucker and catch that one traditional idea and re-apply it to their company with a new twist.

The best game designers adore playing a game of Risk for the 100 millionth time because see some new nuance of the rules they may be able to use. The best CEOs thumb their dog eared copy of The Definitive Drucker and catch that one traditional idea and re-apply it to their company with a new twist.

The best designers read comics keeping up on the popular taste, parse arcane roleplaying game rules just to see how they affect the gameplay, and/or surf the latest games on RealArcade to see what other designers are doing. The best CEOs scan through AdAge with a close eye on Neilsen’s new rating system and how it’s affecting game sales, review differing financial models to see how they could improve business and profits, and/or pick up the latest Harvard Business Review to see how the army’s new “idea-as-currency” system works.

Think of it this way no one would never move lead audio engineer to lead artist or lead programmer. The skill set isn’t the same. The temperament isn’t the same. Nor is the passion. The same is true with a CEO. Her or his main focus and desire must be business design, not game design.

And yet the game industry is filled with CEOs who are unhappy designers, programmers or producers stuck in the role of running the whole shebang. Topping this is a fear among top management of losing control when moving people around. The results can be disastrous.

One example of how this plays out is first publishing deals. The story of poorly crafted first publishing deals is so common in the industry; it is almost taken as fact that all first deals have to be horrible for the developer. The result is that a company comes out with a successful first game, the company reaps little rewards, and is forced to take whatever comes along thus perpetuating a downward spiral. A great businessperson lives and breaths negotiation as a great designer intuitively understands gameplay algorithms. They catch that one clause in the contract that allows additional post production marketing to be taken from net totals. And it is instinctual for them to review each potential publisher’s profit and loss sheets for the last three years. And a great businessperson is not blinded by the need to make a game and understands that saying no to this deal may be the best way of getting that deal.

Though it’s always easiest to take these steps at the first phase of start up, companies retrench all the time. Developers face key moments where this process can have the most effect: prior to a large growth spurt, when a founder leaves or is in a financial crisis. Many game studios redefining themselves after their first game is published go through some transition.

Microsoft did it. LinkedIn did it. Joost just did it. They successfully moved the head honcho out of the the CEO and into another position.

In 2000, Bill Gates graciously handed the helm to Steve Ballmer, and moved to CTO, something close to his heart. In a long planned move, social networking company LinkedIn founder and company visionary Reid Hoffman moved to president and brought in Dan Nye to run the overall company.

In June, Joost’s CEO and one of the founders, Frederick De Wahl, moved over to Chief Strategy Officer, installing Michelangelo Volpi in his place. All three ceded the top position because they knew the company would be better led by someone with more experience who loves running a company. At the same time, they satisfied their own passions by moving back into doing what they love.

Peer-to-peer TV technology Joost

No one is going to move an entrenched CEO without harming a company. But if, as the CEOs above did, that person looks at what they are doing for themselves and to the company, they can transition smoothly.

A game’s publisher and a company’s corporate board both safeguard the financial integrity, quality and timeliness. On a macro level both stay outside the day-to-day company operations while demanding results through the development of goals and require accurate high level reports on a periodic basis. They also provide selected expertise when needed. A publisher hires, reviews and fires a company, the board hires, reviews and fires the CEO.

When the publisher and development company know their roles and work well together, the results are phenomenal. The milestones act as goalposts for a game, spurring the company to act effectively and productively. Honest criticism leads to clear decisions about what should be cut, revamped or kept. In a great relationship publisher and developer share resources, whether it’s programming expertise or marketing art. The same goes for a highly tuned corporate board.

Note that a board and the corporate leaders should not be of the same people just as publishers need to maintain some distance from the development houses they hire. Just as bad publishers can micro manage game design; enmeshed boards want a hand in hiring and firing of employees. Intertwined corporate boards lead to blindness. They give only positive feedback when factual feedback is vital.

The size of a company doesn’t matter. Even tiny companies benefit from having a well run board.

So who should be on the board? From the company side, the CEO and someone representing the financial side of the company. Separating these two out is vital. Even in the smallest companies benefit from having a professional financier prepare and deliver clear, concise reports. Company legal counsel should be present.

Some of the make up of the board is dependent on the focus of a company as well as its culture. A tech heavy game company may wish to have their CTO aboard, whereas one more customer centric may have a representative from a super-user group. Of course, main investors often have board seats in order to ensure their stake in the company.

Other expertise is brought in as needed. Depending on where the company is in their cycle, a board may have Human Resources called upon to give a recruiting report, or have the Director of Business Development to list out upcoming opportunities. Programming may decide to put together a list of things they want to patent.

Equally important is the independent board member.

Though most start-ups and small companies won’t be able to get an experienced media conglomerate president right off the bat.

But it never hurts to ask. There’s a vast pool of university professors, retired corporate executives and other business entrepreneurs who willing to serve on boards if asked. Look at the following boards:

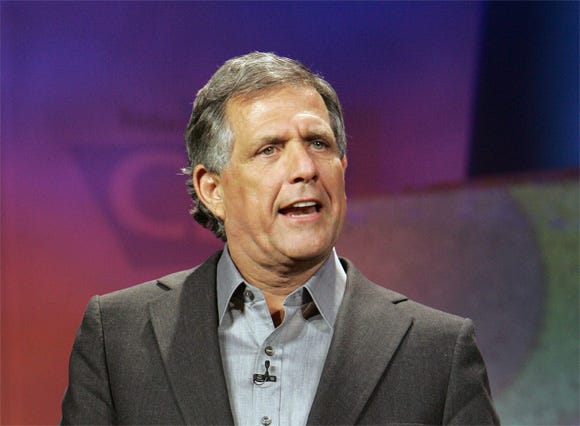

Bethesda Softworks has Leslie Moonves, President & CEO, CBS Corporation, Harry E. Sloan, Chairman & CEO, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Robert S. Trump, President, Trump Management, Inc. Stormfront Studios recruited Tony La Russa, the manager of the St Louis Cardinals Baseball Team, and Seth Williams, formerly of Paramount Television Group, New Line Cinema among others. Limelife asked Terry Wheeler, the former President and CEO of the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association (CTIA) and the former President of the National Cable Television Association (NCTA).

CBS President & CEO Leslie Moonves

If it sounds like name dropping, it is. Each of those names has a huge amount of business experience, contacts and networks behind it. Unlike a board completely composed of company owners and employees, these businesses chose to attract a wide range of expertise to help guide them forward. They stand outside the corporate politics and are free to ask very tough questions of those that bring them information. Their experience brings a refreshing energy and solid ideas to a company.

The executives are like game leads. They are a company’s think tank, architects of its design, guardians of its focus and cheerleaders. They also must be a company’s conscience, using clear eyes to bring the truth, both good and bad to the forefront. Drawn from the main prongs game development they often include programming, art, production, sound and design. It goes without saying that the team needs a business development executive, someone who’s sole job it is to bring in the customers, be they publishers, venture capitalists, government grants, advertisers or end users.

Equally important, though often dismissed, are finance and operational executives.

Every company must have its financial geek. The Financier, often a called a CFO, is not an accountant, just as a programmer is not the chief engine architect. A successful company must spend the same amount of time and energy on their money as they do on their main product. And the expert running the finances should be as talented. She or he must create a financial model which is the economic engine of a company. At any moment the CFO must be able to give a true picture of how much money a company has, what it’s spending it on, where it potentially will be in three, six and nine months, and what assumptions lie under those predictions.

Every company also needs to have its operational geek. Legal philosophy, human resources, marketing, facilities, IT and a host of other structures grow within a company regardless of whether or not someone is guiding them. Successful companies think about how they implement each one instead of allowing their budgets and policies to sprout in the wild, getting them to all work together instead of undercutting each other and creating possibilities for endless rework. Operations mirrors production. Though game development can survive without production, it doesn’t thrive. So the last role that needs to be filled on any executive team is operations.

As the saying goes, size doesn’t matter. A company exists to make money; otherwise it would be a social club. It produces something somewhere by someone. All those “somes” need resource, time and legal management outside their duties. Therefore, tiny companies have financial and operational needs. Huge companies have more layers, spreading out the subsections of finance to support their various substructures.

Ultimately, the best chose to have one person at the helm of each of these business areas to provide consistent, strategic vision. What small companies don’t have is a single person filling these roles. Often time these are additional duties. Taking the time to recognize them as independent functions, finding someone with the skills and drive to do them and bestowing them with high level responsibility and power goes a long way to ensure success.

All executives, regardless of their specialty, must have a basic understanding of company economics and operations just as all leads fundamentally know how their specialties interact with the game engine. They have to know how to put a budget together and read a spreadsheet. Otherwise they make poor decisions.

An art leads know how to enlarge their textures without slowing the game to a crawl. Lead Designers must understand the fundamentals of scripting well enough to guide character behavior. In the same way, every executive must have a fundamental grasp of finances. They must understand what the real cost of an employee is including hiring costs, insurance and salary, what the financial relationship is to a day of slip in dollars and cents, and exactly what is generating the company’s profit at the moment and what will generate it in the next year.

A company doesn’t need a passionate businessperson at the helm, a robust and diverse board, and a talented executive corporate team to survive. Companies survive well enough without them all the time. What they fail to do is thrive.

Those at the top tier ground themselves first by defining these roles then recruiting the best people to fill them. Then they must take on the next challenge: pin pointing the focus. We'll visit that topic next month.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like