Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extensively-researched piece, former Ubisoft associate producer, who has a masters in corporate finance, takes a long hard look at precisely how films are funded and pulls apart the question of whether the same could work for games.

September 20, 2012

Author: by Yann Suquet

In this extensively-researched piece, former Ubisoft associate producer Yann Suquet, who has a masters in corporate finance, takes a long hard look at precisely how films are funded and pulls apart the question of whether the same could work for games.

Publisher financing has been the dominant financing system in the video game industry for more than 20 years, and is a system we're all very familiar with. It involves two players: the publisher with the money, the distribution connections, and the marketing savvy -- hence the power -- and the studio with the ideas and the development expertise. Forgive this Manichean picture.

This financing system is a subject of much debate in our industry, and that mainly on two points. The first bone of discontent is the milestone system. Typically, studios that sign a development contract with a publisher will sign it in one of two forms.

The first one is called a "work-for-hire" contract, and is where a publisher contracts a studio with the development of a game and pays a previously agreed upon fee, upon delivery of milestones.

The other is the "royalty advancement" model, where a studio pitches an idea to a publisher, who -- for the argument's sake -- agrees to finance the development of the game. The publisher finances the development through royalty advancements that are paid out in installments against the delivery of milestones.

This system causes two problems for the studios. The first is that it can create a gap between a studio's payables (studio overhead costs and salaries in particular) and receivables (payments from the publisher). Studios have recurring expenses but less predictable revenue: if a publisher wants to have a change made and decides to withhold the milestone payments until this change is made, the studio is left in a tough cash position. With this system, the studios can be left at the financial mercy of their publishers.

The second problem is that the milestone system severely constrains game development for the studios. Under both contracts, the publisher retains a large part of the creative control and makes sure his vision is carried out with regular control through the milestones: he hedges his risk by making sure the development is going according to his plan -- which is understandable since he's paying for the development, marketing, and distribution. This prompts independent developers to complain that their creativity is being restricted and that their work is transformed into mere execution.

The second point of discontent is a direct expansion of the previous one, and is a question of the overall balance of power and reward between publishers and studios. The publishers bear the financial risks for the project so they tend to take a large part of the revenue and the credit, and retain ownership of the Intellectual Property (IP). The balance of power and reward clearly tilts in favor of the business side of the game industry, and not in favor of the creative side.

It seems only logical that people would start thinking about financing their games with alternative financing methods that could address these issues.

Concerning the issue of milestones, one often stumbles upon opinions of industry professionals across the internet who ask if it wouldn't be just as good if games weren't financed on a milestone basis. Wouldn't game development work just as well or even better if a financier -- be it a publisher or someone else -- trusted the team they invested in with the development of the project?

The problem with that question is that it has no answer. Of course, you might get lucky and successfully finance a project where, let's say, the financier pays the studio the whole budget upfront, never intervenes or controls the development process, and only receives the final product at the agreed upon date and to the exact specifications. You might even get luckier and finance a streak of successful projects like that.

However, there is no way to draw a definite conclusion as to which ones are good financing methods and which ones aren't. A series of successful investments is not proof that a particular financing method is good: the part left to chance is just too big.

This is also true for publisher financing. Publisher financing is just the result of decades of accumulated experience in game development, so one might think it's the most adapted model for financing games the industry has come up with, yet. But that doesn't make it the best method and it shouldn't stop people from looking for alternatives.

The question that can be answered, however, is the question of balance of power and reward. With a specific financing model comes a specific structure or contract that defines the rights and duties of the parties involved. By thoroughly analyzing a specific financing method, it is possible to draw conclusions as to what would happen if it were applied to game development today.

That is what this article ambitions to do, concentrating on a financing method that is widely and successfully used in the motion picture industry today and which therefore raises much interest in the video game industry: project finance.

One of the most prominent critics of publisher financing in recent times has been NESTA, the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts. NESTA is an independent body with the mission to make the UK more innovative. In its report The Money Game: Project Finance and Video Game Development in the UK, dated February 2010, NESTA argues that while publisher financing has had largely positive effects on the industry, it is also hindering its further development in certain ways. It further argues that project finance like it is done in the motion picture industry could solve many of the addressed concerns.

(In this report, NESTA focuses its argument on the UK, but its arguments are relevant to the industry in general.)

According to NESTA, publisher financing has been beneficial to the video game industry in three ways:

First, publishers have been the primary source of funds to an industry worth an expected $78.5bn in 2012 according to Reuters, and that represents tens of thousands of jobs worldwide. NESTA recognizes that the staggering development of the video game industry was almost exclusively made possible thanks to publisher financing.

Secondly, publisher financing has provided developers with a high sense of security, as publishers rarely back out of signed publishing agreements with development studios. The developers can therefore count on a regular and secure flow of funds as well as on more generalized support (relationships with distributors that ensure visibility for the game, etc.) over the duration of their projects.

Finally, publisher financing has been around for 20 years. Relationships have been built between the parties, and in particular between publishers and retailers, reducing to some extent the risk of shipping a game to market -- which benefits everyone.

While this is all positive, NESTA further argues that overreliance on publisher financing might actually prevent the (UK) video game industry from unlocking its high growth potential.

The first major drawback, according to NESTA, is that in this type of financing structure, the publisher retains ownership of the IP, which is "a crucial source of long-term value". The direct consequence is that it is getting harder for (UK) studios to "[leverage] their creative talent and ingenuity … at least with publisher-backing". Additionally, NESTA argues that the studios do not get a big enough share of the profits of the games they developed.

Secondly, NESTA argues that publishers do not commission or finance enough innovative game concepts, and that that financing policy hinders the industry's creativity. As the biggest financial risk lies with the publishers, they would rather finance proven concepts, all the more since development costs have increased dramatically in comparison to the previous console cycles.

This trend is actually amplifying late into the current console cycle: in an environment dominated by strongly established IPs, large publishers are commissioning fewer original IPs, as the investment and risk to establish a new IP are considerable. For example, in an interview with GamesIndustry.biz at Gamescom 2010, Alain Corre, executive director at Ubisoft, stated that "especially in this part of the cycle of the consoles, we [at Ubisoft] are cautious now to introduce new brands". So the trend is for publishers to commission fewer original IPs as the development budgets escalate, and to take even fewer risks late into a console cycle. According to NESTA, this makes it very hard for innovative studios to leverage their potential.

Finally, while publisher financing is adapted to the development of console and PC games, NESTA argues that it isn't to the development of social and online games, as they "require substantial support and a sustained stream of content updates after release." Hence publishers would rather have their in-house studios develop those games. As a consequence, development studios that do not have access to other sources of financing will be unable to seize growth opportunities in those promising markets.

In NESTA's eyes, publishers are, to some extent, crippling the video game industry. In order to solve this, "new financing instruments are needed". These instruments are already being effectively used in the motion picture industry, a more mature creative industry than video games. Indeed, "[the film industry] offer[s] production companies a wider range of financing options, including project -- as well as corporate -- finance drawing on external investors".

External corporate financing is basically your average financing method for a company. The company will finance itself, either through debt (from a bank or on the financial markets) or equity (issuing shares, usually on the financial markets).

For NESTA, introducing project finance instruments would have very positive consequences on the video game industry, as they would allow the studios to leverage their creative talent and find an alternative to the constraining publisher financing deals.

For one, in a project finance deal, studios would be able to retain their IP. NESTA assumes that external investors are not interested in keeping the IP; as such, the studios could then exploit it through different channels and reinvest the proceeds in innovation and growth.

Secondly, external project finance could be a solution to financing riskier projects. By co-financing a game, both the publisher and the financier reduce their financial commitment (hence their financial risk) so in theory, they could finance more innovative, riskier games. Their investment would then roughly have the same risk profile than before.

Finally, project finance would help our industry grow by attracting capital from external financiers. Indeed, NESTA argues that project finance is a better way to invest in the game industry than buying a publisher's stock. The performance of standalone projects is easier to monitor than when projects are bundled together. When investing in a publisher's stock, financiers invest in the company itself, which has numerous projects; hence they do not know how their money is spent and if it will provide the expected return. By investing directly in a project -- in this case a game -- they will have a better overview of their investment.

NESTA sees film-inspired project finance as a way to unlock huge potential for the video game industry in the UK and by extension, for the video game industry in general.

But can film inspired project finance deliver on NESTA's hopes?

To answer this question, this article is going to first explain the basics of project finance before analyzing how project finance is applied in the motion picture industry. It will explain its mechanics and highlight the reasons that push film studios and project financiers to sign that kind of deals. It will then draw conclusions as to what the results could be in the video game industry.

Before going into how the latest film financing structures work, this paper will take a quick look into the logic of project finance, which film project finance is heavily inspired from.

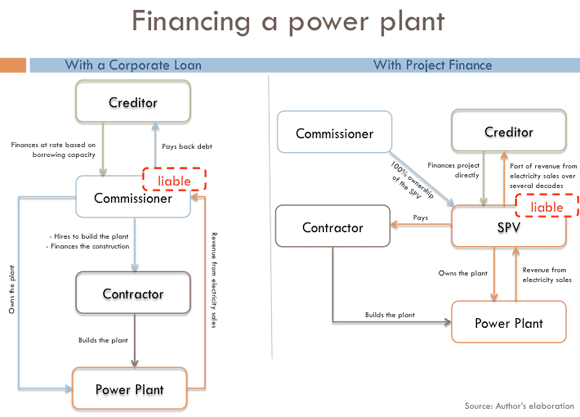

A rapid introduction to the basics of project finance: Project finance has been initially developed to finance large and very costly infrastructure or industrial projects, such as bridges, power plants, highways, mines...

Using regular corporate financing, it would be very hard for a company to finance several projects of large magnitude at a time, because they would impact its balance sheet, i.e. its borrowing capacity, immensely.

With just a handful of projects like these in the pipeline, the company would be so crippled with debt that no bank or equity investor would agree to further finance it and in the worst case, the company would go bankrupt.

Additionally, in case of a project's failure, the company would be directly liable to its creditors. With projects of that magnitude, just one failure could severely damage even the biggest companies.

As such, a financing method has been developed to fund large infrastructure or industrial projects; it is called project finance, and is based on a different reasoning than regular corporate finance. Instead of relying on the company's capacity to reimburse the debt, "project financing is a loan structure that relies primarily on the project's cash flow for repayment, with the project's assets, rights, and interests held as secondary security or collateral," according to Investopedia.

This means that the creditor will finance the project itself rather than the company that commissions the project. For that to be possible, a new company that is the legal framework of the project is created -- in financial terms, it is called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). It is that SPV that is the owner of the project, and as such gets financed and is responsible and liable for the project.

Let's take the (simplified) example of a power plant. An energy company (the commissioner) needs a new power plant. An investment bank sets up the project financing structure, finds the creditor, and creates the SPV. The SPV will be financed by the creditor through debt, and will hire the contractor to build the plant. The commissioner owns the SPV 100 percent (he is the sole equity investor), but the SPV owns the power plant, so it also holds all the rights and interests of the project. As such, in case of failure, the creditors will claim reimbursement from the SPV directly, and not from the commissioner. Finally, once the plant is built, the creditor will recoup his investment by cashing in part of the electricity sales from the plant, over a previously agreed upon period (usually several decades).

This example is pictured below.

Hollywood's glitter has always been attractive to financiers.

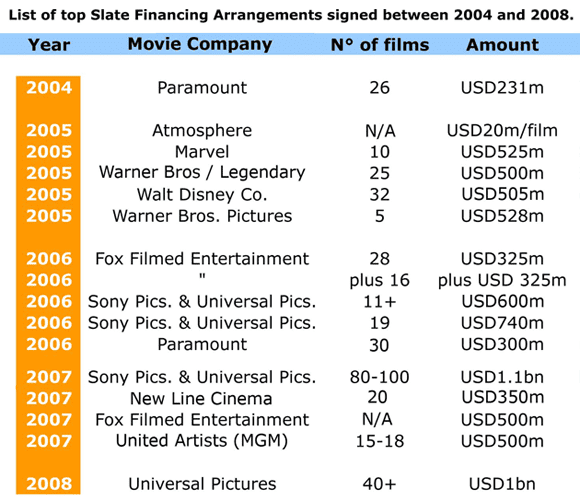

But in 2003, Paramount executive Isaac Palmer revolutionized film finance by developing the first film financing structure specifically tailored to the needs of modern, sophisticated investors: Slate Financing Arrangements (SFAs).

The revolution lay in that instead of investing in just one movie, financiers would invest in a pool of several movies, on average between 10 and 25 over three to five years, which provided intrinsic risk diversification. That slate would be owned by an SPV, in which both the movie company and the financiers would invest.

The second revolution was that the deal was structured in a way that it offered a wide array of financial instruments to invest in (senior debt, mezzanine debt, and equity), each one with a different risk profile matching the investment strategy of a different type of investor. This broadened the appeal of film finance at Wall Street immensely.

Senior debt is the debt with the highest priority level: it's the least risky investment in SFAs.

Mezzanine debt is subordinate to senior debt. As such, it is riskier.

Equity is repaid last and is the riskiest investment. It also has the highest potential returns.

In fact, Hollywood never saw so much outside money flow in than between 2004 and 2008: over that period, numerous deals in the nine to 10 digit range were signed, which are referenced in the list below.

Click for a version of this chart with expanded information

And while external capital has somewhat dried up due to the financial crisis, with many large financial institutions exiting SFAs, some major players remain in that business today, one of the most prominent being Ryan Kavanaugh's Relativity Media.

SFAs, because of their sheer size, are the playground of only the biggest companies in Hollywood. That includes the majors and large independent production and distribution companies.

The majors are the six biggest companies in Hollywood, commanding roughly 90 percent of the US box-office. They are Paramount Motion Pictures Group, Warner Bros. Entertainment, Sony Pictures Entertainment, The Walt Disney Studios, NBC Universal, and Fox Entertainment Group. Their businesses include, among other things, producing and distributing motion pictures.

Large independents include production companies like Marvel Entertainment before it was bought by The Walt Disney Company in 2009, but also companies that are active in distribution as well, but are not as massive as the "big six", like Lionsgate and Relativity Media, for instance.

Financiers who get involved in SFAs are sophisticated investors, hedge and private equity funds in particular. During the '00s, stock markets were slow, returns on real estate were lagging, and interest rates were low (Ineichen, 2008).

As a consequence, hedge and private equity funds with large pools of capital to deploy started looking for alternative investments with a low correlation to standard asset classes (stock, bonds and cash) that could bring higher returns (Reif Cohen, Kopelman, Fishman, & Ramirez, 2006). SFAs matched those criteria perfectly, and private equity and hedge funds invested large funds in equity stakes.

Additionally, with the deals being structured so as to offer a wide range of investment products, pension, and mutual funds, banks were active investors in film slates as well, mostly in debt products.

The mechanism of an SFA

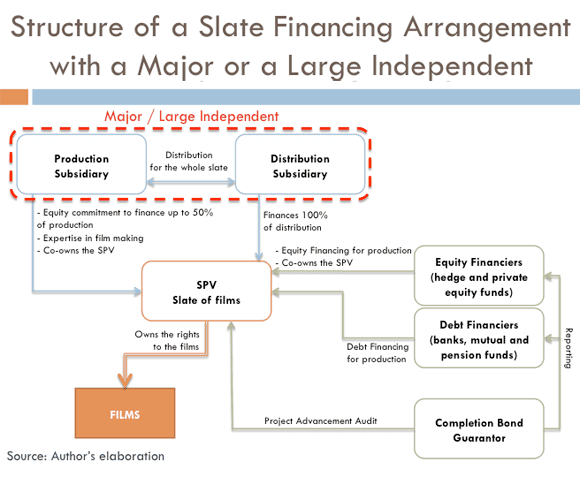

SFAs are inspired by project finance, so they have an SPV at their core. That SPV will hold the rights of movies in the slate. Films being a much riskier investment than infrastructure or industrial projects -- the revenues are far less foreseeable than with a power plant for instance -- the SPV holds a number of films, with statistical research suggesting 20 to 25 films to reach a satisfactory level of diversification (Reif Cohen, Kopelman, Fishman, & Ramirez, 2006).

Just like in any project finance deals, the financiers are paid back on the cash-flow stream generated by the projects (in this case, the films), rather than from the parent company producing the films. In order to assess the value of the projects they are investing in, financiers compute cash-flow forecasts that are typically based on sales over a 10- to 15-year period, beginning with theatrical release, and including DVD, Blu-ray and video on demand sales, release to cable television, broadcast television networks both domestic and international, and in-flight airline licensing (Mezzanotte, O'Connell, Kelley, Weilamann, Tillwitz, & Buckler, 2010).

Prior to the development of SFAs, major studios and large independent producers/distributors would not commit any -- or very little -- financial resources to their production and distribution budgets: they would entirely rely on various exterior financing for that -- through tax rebates and loopholes, pre-sales on international rights, and co-production agreements. In SFAs, however, movie companies started to invest considerable funds in the production capital, often as much as 50 percent of equity, and the distributor would entirely self-finance distribution.

Third party financiers contribute the remaining funds for production, with hedge and private equity funds investing the remaining equity stake in the SPV. This makes the SPV a sort of joint venture between the production company and the equity financiers.

SFAs also differ from previous film financing models in that a distribution agreement is signed with a major or an independent distributor for the whole slate. The production company retains the entire distribution rights against a pre-negotiated distribution fee with the distributor, usually in a range of 10 to 15 percent of gross revenue. (When a major or a large independent is producing the movies, it usually distributes the films through its in-house distribution business.)

Of course, the financial success of the deals remains contingent upon the completion of the films' production. To mitigate the operational risk, third party financiers hire a completion bond guarantor, who ensures, through very regular production audits, that the production company will in fact deliver the completed project to the distributor in time and in budget. If not, the completion bonder is liable for some of the losses incurred by the financiers. The completion bonder is basically an insurance policy against operational failures.

This graph shows a typical SFA arrangement with a major or a large Independent, where the production and distribution businesses are part of the same company:

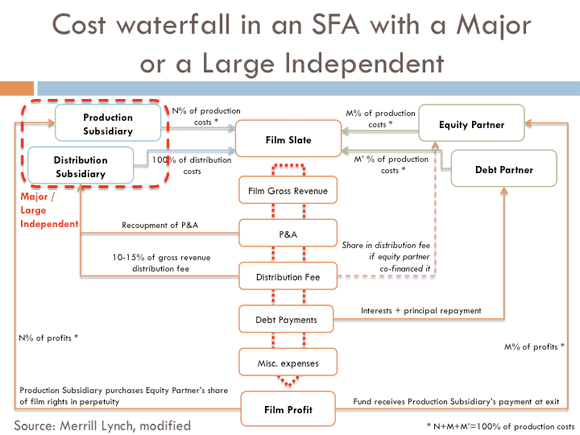

Cost waterfall in an SFA

The cost waterfall in SFAs has a particularity that clearly favors the movie companies, and that sets it apart from previous film financing structures: the distribution company recoups its Promotion and Advertising (P&A) expenses and receives its distribution fee of 10 to 15 percent of gross revenue prior to any paybacks to the financiers. (However, and while merely sporadically, equity financiers have started to participate in the distribution expenses so they are sometimes entitled to a share in the distribution fee as well.)

Only after does the slate repay the financial partners who invested in debt products.

After other miscellaneous expenses have been paid, the equity partners -- the production company and the equity financiers -- share the revenues according to their initial commitments.

Once all the projects have shipped, the SPV is dissolved. The equity partners co-owned the SPV, so upon dissolution, they also co-own the rights to the movies. Financiers have no interest in keeping these rights, but the movie companies do. So the production company buys back their share of the film rights from the equity partners, who cash in additional revenue.

The diagram below shows the waterfall with a major or large Independent.

While the glitter of Hollywood has always made film financing very attractive to top financiers, SFAs proved even more popular than any previous forms of film finance.

This begs the following question: what were the movie companies' and the financiers' reasons to do so many and so large film financing deals?

The motivations of movie companies to sign SFAs

A film industry executive quoted in a Merrill Lynch report dated September 2006 on co-financing in the film industry summed up the motion picture companies' motivations to sign SFAs in the following terms. "This is the sweet spot of motion picture financing. You retain creative control, you've got a financial partner, and you're allowed to take a distribution fee. The economics are quite attractive." (Reif Cohen, Kopelman, Fishman, & Ramirez, 2006)

While the economic realities of film financing had somewhat evolved by the end of the decade, SFAs remain a very attractive way for movie studios to finance their films nonetheless.

Risk management

One of the principal motivations for studios to sign SFAs is risk management.

They allow studios to manage their risks in different ways:

- Studios can increase their output at a stable level of investment. That way, they can increase the supply for their distribution business, a business less risky and more profitable than production.

- Studios tend to co-finance movies that consume a large part of their production budget to even out the commitments to all their projects. By trying to commit roughly the same amount of money to all their productions, studios reduce their financial exposure to bigger projects (they reduce the variance of their film portfolio), reducing their overall financial risk. (Goettler & Leslie, 2004)

- However, and contrary to popular belief, studios do not resort to co-financing for riskier projects. One could think that by having a financial partner, they would be prompted to take more risks, since the financier's share would buffer their financial loss in case the film turned out to be a disappointment at the box office. Surprisingly, Goettler and Leslie's research suggests that studios do not co-finance relatively riskier movies: contrary to anecdotal evidence, from the point of view of realized returns, their statistical analysis indicates that co-financed movies are not different from solo-financed movies. Since risk and return are correlated, this means that the studios do not perceive the movies they co-finance as being riskier. (Goettler & Leslie, 2004)

Other motivations

Other motivations for studios to resort to SFAs include:

- Making projects more profitable (in pure accounting terms),

- Project finance transactions are off balance sheet, meaning that the mother company's borrowing capacity will not be impacted and that it won't be liable in case of a slate's failure.

There are a number of reasons studios would resort to film financing to fund the production of their movies, all of them business driven: studios sign SFAs because they make their company less risky and more profitable.

The motivations of financiers to sign SFAs

Financiers have just one motivator to join in on SFAs: profitability.

Financial simulations tend to suggest that SFAs are profitable (Reif Cohen, Kopelman, Fishman, & Ramirez, 2006):

- The Net Present Value (see below for definition) for third party publishers is positive

- Statistical computations suggest that slates are profitable 80 percent of the time when the required diversification level of 20 to 25 movies is reached, while individual films loose money over 50 percent of the time (Reif Cohen, Kopelman, Fishman, & Ramirez, 2006).

The Net Present Value (NPV) values the future returns of a project in today's dollars. It is a way to assess if a project is profitable or not: if the NPV is positive, the project should be undertaken. If it isn't, the project will lose money.

Now that this paper has explained how SFAs work, it is time to look at how a similar financing structure would work in the video game industry.

SFAs are the most refined project finance structures in entertainment yet. This article will therefore look at how this structure in particular can be applied to the game industry, and see if it can live up to NESTA's expectations.

Similar businesses, but not exactly the same players

In the game industry, publishers play a similar role to the majors in the film industry: they are both production and distribution companies. On the one hand, they produce games in-house as well as commission games from independent studios; on the other hand, they distribute the productions they financed as well as foreign games that have no distributor in a specific geographic region they operate in.

Independent game studios are comparable to independent production companies. They look for funds -- albeit through very different channels -- to produce a project and then hand it over to a distributor.

However, SFAs target only the biggest independent motion picture production companies, which have a significant output each year. In the game industry, there are no independent studios that are equivalent in scale to these big film independents.

The need for internal diversification will push financiers to partner with publishers

When making their asset allocations, regardless of the financing structure they use, investors seek diversification to reduce their exposure to any one specific investment.

Diversification is at the heart of SFAs. If project financiers were to invest in video games, they'd need to diversify their investment much the same as they do in SFAs.

At first sight, motion pictures and video games have comparable risk profiles: operational risks are now widely mitigated both in the production of movies and games, hence the biggest financial risk occurs when the products ship to market. Upon release, both products are subject to the same dynamics: release date, competition, audience taste, genre, trends...

However, the motion picture industry can count on two levers that the video game industry doesn't have, and which make motion pictures a less risky business than video games: the star system and secondary releases.

A movie directed by a famous director and starring famous cast will almost automatically attract viewers, while game designers remain largely unknown to the general public.

Plus, movie companies can count on the additional revenue generated by DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, TV, and in-flight sales. This contributes to reducing the financial risk of movies as well. Console games, on the other hand, only ship once.

This entails that third party financiers will demand even more diversification in a slate of games than in a slate of movies. And while no statistical data is available, one can safely project that financiers will need at least 25+ games to sign a deal. No independent studio is able to produce that many games over a period of three to five years.

If financiers were to partner with independent studios, they would have to look for enough different studios with enough different projects to build up a slate and reach an acceptable level of diversification. This would make the project finance deal incredibly complex and difficult to manage, by multiplying the number of parties involved, the contracts, the financial requirements, the egos, etc.

The only place in the game industry where financiers would find enough diversification in one spot is a publisher. Hence it currently makes much more sense for them to work with a publisher than with studios, even if the publisher then subcontracts some of the projects to independent studios.

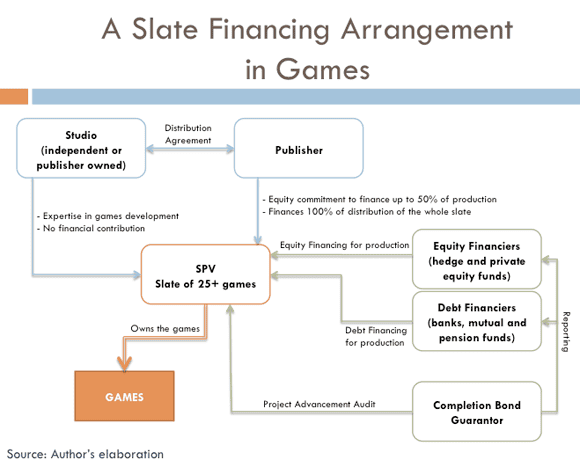

An SFA in the game industry today

An SFA in games today would likely be structured like this:

- An SPV with 25+ games would be set up, and it would own the rights to the games.

- The publisher would finance part of the production development through an equity stake in the SPV.

- It would also finance 100 percent of the distribution and act as the sole distributor for the whole slate.

- The financiers would come up with the remaining production funds in the form of equity and debt.

- The studios -- in-house or independent -- would develop the games using the production budgets and would not commit any funds to the production or distribution budgets.

- A completion bonder would be hired by the financiers to audit the projects' advancements.

The diagram below shows how an SFA would likely look like in the game industry today.

Would project finance live up to NESTA's expectations?

Considering the previously established fact that project financiers would partner with publishers, could project finance live up to NESTA's expectations if it were applied to the industry today? As a reminder, NESTA expects project finance to have the following consequences on the game industry:

- The studios will retain ownership of the IP they created, since third party financiers aren't interested in keeping ownership of it.

- Publishers and financiers will share the costs of riskier projects that would otherwise not get financing.

- Project finance will make the game industry more attractive to external financiers because it will allow them to better control their risk than if they took a share of a publisher's equity. This will prompt them to invest in games and will make the industry grow.

Studios retain ownership of the IP

In the game industry, the IP belongs to the guy who pays the bills. And in today's industry structure, that is the publisher.

Following that logic, if a third party financier takes a partial equity stake in the SPV to finance the development, he'll be entitled to a partial ownership of the IP, proportionate to his stake, once the SPV is dissolved; the other part will be owned by the publisher, who also invested in equity.

NESTA might be right in saying that financiers are probably not interested in owning the IP. They might however very well be interested in selling those partial rights back to one of the remaining parties -- the studio or the publisher -- upon exiting the slate. And in a bidding war, the publisher will most likely come out as the winner. And even if the studio were able to outbid the publisher, it would only own the financier's part of the IP, and would have to buy back the remaining part from the publisher.

As such, and unfortunately for the studios, the publisher will most likely retain ownership of the IP after the completion of the project. Project finance is not going to change that practice.

Publishers and financiers share the costs of riskier projects that would otherwise not get financing

In their statistical research quoted previously, Goettler and Leslie found that motion picture studios do not co-finance relatively risky movies, as discussed above. As such, there is no reason to believe that financiers and publishers would want to co-finance riskier projects in the video game industry.

NESTA: project finance is less risky than in an equity stake in a publisher

In its report, NESTA claims that the performance of standalone projects is easier to monitor than when projects are bundled together, which makes project finance a less risky investment than an equity stake in a publisher.

However, there is an ambiguity here, because NESTA does not specify if it talks about the investment in just one project or in several.

If NESTA is saying that it is less risky to invest in one project finance deal than to buy a publisher's stock, they are saying that it is less risky to invest in one project than it is to invest in several. That goes against one of the most basic rules of financial management: diversification. It is by far less risky to invest in several projects -- and the publisher has several projects in its pipeline -- than in one, regardless of the overview and control one has on it.

But the report might also be saying that it is less risky to invest in several projects -- like in an SFA -- than in a publisher's stock, because the financier diversifies its investment, much like it would with stock, but gains a better overview of the projects, too. However, equity funds are committed to project finance deals under very stringent contracts: both equity partners form a complex joint venture, which is much harder to exit than giving your broker a phone call to sell your stock. The advantage the financiers might get from a better insight into the projects is outweighed by a considerable loss in flexibility.

As for debt investments in several projects, they would indeed be less risky than an equity stake in a publisher, but only for the simple reason that debt is by itself less risky than equity because it is reimbursed far before. However, debt investments are irrelevant here. Debt offers much lower expected returns than equity, and therefore does not appeal to the same kind of investors: investors who would consider buying a publisher's stock would compare this investment with an equity stake in a project finance deal, not a debt stake.

As such, and unlike what NESTA claims, a better overview of the projects a financier invests in is not a relevant argument to attract him to the video game industry.

Potential profitability is key

Investors seek profitability first. This is the only reason why they engage in SFAs in the motion picture industry. As such, for third party investors to finance a slate of games, one would only have to prove that the slate could in fact be profitable.

No statistical research analyzing the potential profitability of a carefully selected slate of games is publicly available, but one can project that if movie slates are profitable, game slates could be as well, provided they are diversified enough.

So NESTA is right in saying that more money would flow into the game industry, financing its growth. However, it would not happen for the reasons it thinks it would.

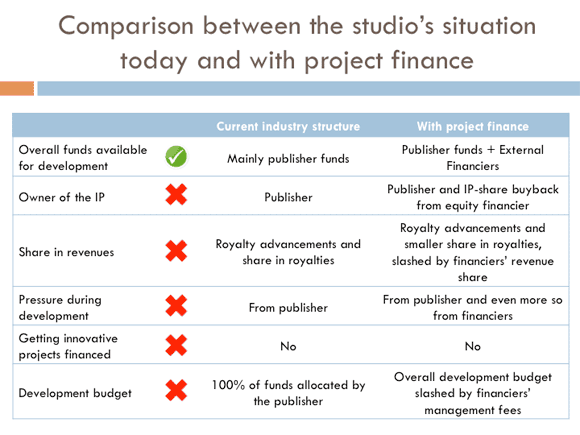

Clearly, project finance does not live up to the high expectations NESTA has in it. So what would really happen if financiers set up a slate of games with a publisher today?

More money would flow into our industry

Probably the most positive aspect would be that additional funds would flow into the game industry, boosting its growth. This would mean more projects would get financed, which would give more work to the studios, and result in more job creation in the industry in general.

Dealing with less understanding creditors

However, this could come at a considerable cost. Indeed, while publishers are sometimes regarded as the evil power in our industry, their decisions are not systematically financially driven; they are also content-driven.

Say what you want, but they understand the day-to-day business of making games -- what makes a good game, delays in development, personality management, and more. They care about shipping good products. They care about time, budget, and quality.

The financiers' job, on the other hand, is to make their assets under management prosper. Their most important considerations are time and budget, and they will make sure the studios meet those objectives first. When Warren Spector created Junction Point Studios, he didn't -- in his own words -- "go the venture capital route or the angel investment route. [He]'d seen too many friends and colleagues fail as a result of having to meet the needs of external investors," he told Morgan Ramsay, in his book Gamers at Work.

In the case of a project finance deal in video games, this means the financiers would put great pressure on the publisher as well as on the studio through the completion bonder, who'd impose even more drastic milestone reviews to maintain the development schedule at all cost. This would make development a living hell for the studios, harm the quality of the projects, and would actually not be that great for publishers either.

High fees would slash development funds

Project finance is an extremely heavy financing structure that involves a high number of parties, who all need to be financially compensated for their work.

Fund managers in the financial industry are compensated -- among other fees -- with a certain percentage of the investment capital they manage for their investors. The same goes with completion bond guarantors who, in the motion picture industry, are compensated with a certain percentage of the production budget.

In a project finance deal in video games, those fees would be paid out from the overall production budget, which would be slashed by an estimated 6 to 8 percent, just in management fees, based on general compensation practices in the motion picture industry: completion bonders charge between 4 to 6 percent while hedge and private equity funds usually take a 2 percent management fee. The direct consequence would be that the games' quality would again be the first to suffer.

The structure would reduce revenues for the studios

Finally, studios would see their revenue share being cut down as well.

Indeed, in publisher financing, the publishers cash in the whole revenue from the game and subsequently pay the studios a share of the profits as royalty.

In a project finance deal, the publisher and the equity financiers share the revenue from the slate. The publisher will therefore see his share of profits reduced and will pay out less in royalty to the studios.

Summary of the consequences of video game project finance for the studios

So while project finance would help our industry grow by providing additional funds, it would do so at a considerable cost. Project finance could make game development a living hell for the creative talent in our industry, and would only worsen every aspect of the current publisher-financing structure.

For the past 20 years, our industry has heavily relied on a financing model -- publisher financing -- that some consider flawed. Project finance, like it is done in the motion picture industry, is seen by many as a way out of this financial model, out of its inequitable power relations and as a growth lever.

While that last part would most likely be true, this article anticipates that project finance is unlikely to change the dynamics in our industry and modify the balance of power between publishers and studios. In the current state of our industry, project finance would only make the balance of power worse, with independent studios suffering the most. They would still not retain ownership of their IPs, nor would they get a bigger chunk of the profits, nor would their riskier projects get financed. They would, however, be under even more pressure to deliver the project in time and in budget, and would have to work with smaller development budgets.

But there is hope for change for independent studios yet. But first, the game industry should shake off its complexes with the film industry: it should stop trying to find the answers in the business models of the motion picture industry and should start believing in itself -- it's not because movies have been around longer that they know better. Instead, video game professionals should focus on seizing the opportunities for change that arise from within the game industry, and there are many.

What makes our industry so fascinating is the fact that it is ever changing. New ways to play and new technologies emerge, new dynamics overthrow the previous status quo and yesterday's leaders will not necessarily dominate tomorrow.

The current industry structure is already shifting, with the recent development of social and mobile games, and also with digital distribution. The latter is a dramatic example of what new technologies can change in the industry's practices, as Trip Hawkins, founder of Electronic Arts explains in Gamers at Work, "Digital media has collapsed the traditional value chain, so financial and distribution leverage are no longer viable means of controlling shelf space and pipelines."

One very popular example of change brought about by the rise of digital distribution is the Indie Fund. The Indie Fund was "created by a group of successful indies looking to encourage the next wave of game developers" by financing their games. This small group of successful indies -- Jonathan Blow, Ron Carmel, Kyle Gabler, Aaron Isaksen, Kellee Santiago, Nathan Vella, and Matthew Wegner -- realized very early that the relationship between independent game developers and big publishers would never work, which prompted them to create the Indie Fund as a serious alternative to publisher financing.

They have a different approach to investment than publishers, because they believe in a different way of making games. They don't want to impose on the creative process, nor do they believe in milestones. They rely on the combined experience of the fund's members to invest in a game and in a team that they know can deliver. They recoup their nominal investment first and then take 25 percent of total revenues until they double their investment, or until the game has been out for two years. At the time of writing, the fund has financed seven games -- including Faraway, Q.U.B.E. and Dear Esther -- roughly three years into its existence. And while no performance data is publicly available, it seems the fund has been performing well.

The Indie Fund seems to be the proof that with the rise of new technologies and opportunities, different financing models are possible where studios get more power and creative control. This is what World of Goo co-creator Ron Carmel explained in his 2010 GDC Talk "Indies and Publishers: Fixing a system that never worked" -- if it were not for digital distribution, the Indie Fund would have never seen the light of day. Ten to 15 years ago, signing a publishing deal was great for an indie developer because it was the only way it could get its games financed and onto the shelves.

Now however, with digital distribution, the indie developer doesn't really need the publisher to get a game out anymore, and can therefore also look for alternative financing methods. And the Indie Fund is just one example of what kind of changes new ways to play and new technologies can bring to our industry.

One thing's for sure: new ways to play and new technologies will push our industry forward and will help it grow. But whether or not they will change the way games are made and will shift more power to the studios is an open question.

Film inspired project finance is, however, not the answer.

Reif Cohen, J., Kopelman, M., Fishman, R., & Ramirez, L. (2006). Inside film finance. Merrill Lynch. New York: Merrill Lynch.

Ineichen, A. (2008). AIMA'S ROADMAP TO HEDGE FUNDS. AIMA'S INVESTOR STEERING COMMITTEE.

Mezzanotte, C. J., O'Connell, C., Kelley, R., Weilamann, C., Tillwitz, K., & Buckler, J. (2010). Rating Global Film Rights Securitizations. DBRS, Global Structured Finance. Toronto: DBRS.

Goettler, R. L., & Leslie, P. (2004). Cofinancing to Manage Risk in the Motion Picture Industry. Carnegie Mellon University and Stanford University.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like