Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

What's the psychology behind cheating and dishonesty, and what are the factors that can reduce or increase dishonest behavior?

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself - and you are the easiest person to fool." Richard Feynman

One of the first concerns that you may hear when you talk about gamification is “But won’t people start cheating?“ Of course people will cheat. But here is the thing: people already do cheat right now. They may not be as honest as you think, and people will always cheat. The question is more of how and how much people are cheating or being dishonest.

Not every cheating is bad. There may be cheating that demonstrates very engaged behavior and may be used by the gamification designer to enrich the game. Sometimes, a way to cheat may be built into the system to give the players the pleasure of taking a shortcut – without noticing that this was a wanted design. Cheat-codes to circumvent specific obstacles of finding hidden treasures (“Easter eggs“) may even add to the adoption of and engagement with a gamified system. And players finding new ways to cheat the system may give gamification designers new ways of making the gamified design richer.

Famously, Captain James T. Kirk from the starship Enterprise (yes, now you know it: I am a total Trekkie) cheated the simulation by reprogramming it. As you may know, the simulation was not supposed to be winnable, but because of Kirk’s cheat he could win. In that case that specific cheat was regarded as an acceptable way to show the capability of a starship commander to come up with an unusual approach to win an unwinnable situation. Much to the discontent of the law- and rule-abiding Spock, who had programmed the simulation.

Cheating becomes a problem in cases, when the players who abide to the rules have the feeling that the game becomes unfair, or that the original purpose of the gamified approach is being diluted. And as a result these players will disengage – and that is the exact opposite of what we try to achieve with gamification: engaging people.

As an example from a professional community, where members help each other by blogging, answering questions, creating help documents and so on, points were an important factor to show expertise. An unintended consequence appeared, as some members got goals set by their managers to reach a certain number of points within a period. Some of these members figured out that by creating multiple users, they could ask a simple question with one of their users, and respond with their other user and reward themselves with points and climb up the point ranking. As you may expect, this behavior had the law-abiding members go ballistic. They did not care so much about the points, but they found that such cheat-pairs diluted the content by adding redundant and often overly simple questions and answer into the system, which made it harder to find the relevant content.

While a certain level of cheating will always be there (and is already there), we want to make sure to keep it at a certain level, react at cheating, and enforce rules. For that we need to understand the reasons when and why people cheat.

Are there ways to reduce dishonesty and cheating in a game? Professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, Dan Ariely researched, when and how much his test participants would cheat. In one study, Ariely asked a group of students and undergraduates to take a test consisting of 50 multiple-choice questions. When the students were done with the tests, they were asked to transfer the answers from their worksheet to a scoring sheet. For every correct answer students would receive 10 cents.

Now here is the twist: the test subjects were split into four groups. The first group had to hand the worksheet and scoring sheet to the proctor. For the second group the scoring sheet had a small, but important change: the correct answers were pre-marked. Would they cheat more? Anyhow, they still had to hand over both the work- and the scoring sheet. The third group finally also had the correct answers pre-marked, but the students were instructed to shred their worksheets and only hand the scoring sheets to the proctor. The fourth and final group again had the scoring sheets pre-marked with the correct answers, but the students were instructed to shred both the work- as well as the scoring sheet and just take the amount of 10 Cent coins out of a jar. Both the third and fourth group had basically carte blanche to cheat to the maximum, as nobody could verify their claims. What were the results?

According to Ariely’s study, the first group that had no chance to cheat answered 32.6 of the 50 questions correctly. The second group, with an opportunity to cheat (but the risk of being caught) had 36.2 questions correct. As the group was not smarter, they had been caught in a bit of cheating and “improving” their scores by 3.6 questions. The third group that had the chance to cheat without being caught – after all their original worksheets had been shredded before anyone else than themselves could take a look at them – reported 35.9 correct questions. Which was about the same as the second group. The fourth group – remember: the one with carte blanche to cheat – reported 36.1 correct answers.

The surprise here is not that people cheated, but that the risk of being caught did not influence their amount of cheating. The students didn’t push their dishonesty beyond a certain limit. The question was if there is something else which is holding them back? Maybe this could external controls to enforce honesty? Prof. Ariely who was skeptical about the power of external controls – as we are skeptical about extrinsic motivators - tried something else. in another experiment he asked two groups of students to solve a test with 20 simple problems. Each participant had to find two numbers that would add up to 10. They were given 5 minutes to solve as many problems as they could, after which they were entered in a lottery. Once in the lottery they could win ten dollars for each problem the solved correctly.

The first group, which served as control group, had had to hand the worksheets to the experimenter. The second group was asked to write down the number of correct answers and shred their original worksheet. This basically was the group that was encouraged by the setup to cheat. But the participants were given another task prior to working on the main task: half of the group was asked to write down the names of 10 books that they had read in high school. The other half was asked to write down as many of the Ten Commandments as they could remember.

The result was clear: the control group had solved on average 3.1 of the 20 problems correctly. The second group that had to recall 10 books from high school achieved an average score of 4.1 correct answers (33% more than those who could not cheat). The third group – the one that had to recall the Ten Commandments – had on average 3 problems correctly solved. Although they were not asked to say what they were about, but just to recall them, the simple request to write them down had an effect on the participants’ honesty.

The conclusions for us are that although people cheat a little all the time, people don’t cheat as much as they could. And reminding them of morality in the moment they are tempted tends to make them more likely to be honest. A players’ code of conduct that reminds the players to behave ethically – similar to oaths or pledges that doctors and other professionals used to have - may be a good way for some player communities to keep cheating at a low level.

Is cheating more eminent, when money is involved? After all, tangible rewards are more useful than just points. Dan Ariely asked himself this as well, so he came up with a couple of interesting experiments to test this.

In his first experiment he put six packs of Coke cans in dormitory fridges. The ones that are accessible for all students living in the dormitory. Over the next days he frequently returned to check the Coke cans. Ariely found out that the half-life of Coke isn’t very long. After 72 hours all Coke cans had disappeared.

What about money? In some of the fridges Ariely placed a plate with six one- dollar bills – and did the same. He frequently returned and found a completely different result. After 72 hours, all off the one- dollar bills were still on he plate. Now this was a stunner. People take goods, but leave the money, although both are from a value perspective similar. Is the perception of dishonesty dependent on whether we are talking money or something that is one step removed from money?

To understand this behavior better, Ariely came up with another experiment. He asked students at the MIT cafeterias to participate in a little experiment by solving 20 simple math problems. For every correct answer they would get 50 cents. Ariely split the students in three groups: the first group had to hand over the test results to the experimenter, who checked the answers and gave them the money. The second group was told to tear up their worksheet and simply tell the experimenter the results to receive the payments. The third group was also told to tear up their worksheet, but would receive tokens instead of cash. With these tokens they would then walk 12 feet over to another experimenter to exchange the tokens for cash.

What happened? The first group was, as you already know from the other experiments, the test group. They solved an average of 3.5 problems correctly. The second group who had been instructed to tear up their worksheets claimed 6.2 correct answers. Basically, Ariely could attribute 2.7 additional questions to cheating. But the participants in the third group – who were no smarter than the participants from the former two – claimed to have solved 9.4 problems. 5.9 questions more, an increase of nearly 170%.

As soon as the non-monetary currency was inserted, people felt released from moral restraints and cheated as much as possible.

The Austrian artist and world vagabond (as he calls himself) Thomas Seiger did an interesting art project. He gave money away. He positioned himself at busy squares in cities all around Austria, carrying a tray with coins and banknotes in his hand. Attached to the tray was a sign saying “Money to give away.“ In total the amounts that he carried on the tray were several dozen Euros.

After traveling through South East Asia, he realized that material possessions are interfering with his understanding of what life is and decided to sell his worldly possessions and give the money away. But this turned out to be harder than imagined. People who stopped, incredulously asked him whether there is a catch or so? “No,“ he kept replying, “take as much as you want, no strings attached.“

Still, most of the people did not take money. Those who came, picked small denominations, but often they came back to return the money. They felt bad or felt embarrassed having taken the money. “Taking money is more difficult than giving,“ says Thomas. A group of 7 graders approaches him as well. After some hesitation, the most courageous boy moves forward to take a coin, but immediately the girls in the group call him back harshly. In the end one of the 7 graders takes out his wallet, and empties it on the tray. One after the others tosses more money on the tray, ignoring the protests from Thomas.

If Seiger had given away something else, like candy or balloons, he would have run out faster of his stock. After all it’s not money and people can justify it better, like the balloon or candy is for my son.

Both Ariely’s experiments and Seiger’s art project showed that dealing with cash makes us more honest. But removing us from money makes it more likely that people start cheating or loosing moral restraints.

This is an important lesson for gamification designers. If you reward players through extrinsically means, you set them up for cheating. This way you also make sure that the game masters will have a significant amount of their time spent on dealing with cheating. Finding, punishing and eliminating cheaters, constantly adapting rules to make cheating harder, dealing with dissatisfaction of “honest“ players, and always fearing Damocles’ sword of your players disengaging in troves once cheating takes over. Another reminder that rewards should be intrinsic, and not extrinsic.

One other aspect of when players are more likely to cheat was when we learned about the reactions to winning or losing in competitions by Martá Fülöp. Players with narcissistic behavior tend to feel entitlement to winning and fairness becomes an afterthought. They are more likely to cheat.

Drawing from the studies and outcomes above, we have a number of options to reduce cheating. The first cluster of options is through a balancing act of value, effort, and transparency.

Decrease the perceived value of rewards

Increase the effort required to game the system

Shamification

By using intrinsic rewards without transferable value in the real world, or perks that have only a low exchangeable value, then players will be less encouraged to cheat. To prevent getting players in the system that are just aiming for the rewards and not adding any value to the system, use rewards that have a large perceived-value differential between the target audience and the rest of the world.

The next approach is to make the combination of the rewards metrics so complex, that they cannot be easily understood how to game them. An example would be the Google PageRank. The way Google defines at what position a link comes up I the search results is a secret sauce that is also subject to constant change.

If you use metrics that are less susceptible to gaming and require high effort, you can also keep cheating at lower levels. Michael Wu describes the following two variations that demonstrate how to increase the required effort:

Time-bounded, unique-user-based reciprocity metrics (or TUUR metrics) -> e.g. number of Retweets

Time-bounded, unique-content-based reciprocity metrics (or TUCR metric) -> e.g. number of Likes

And then there is the opposite technique not to make the rewards metrics hidden, but transparent. Show the public how players achieved their rewards. This way cheating patterns can be easily detected by others and create social shame and accountability. I like to call this approach “Shamification.“

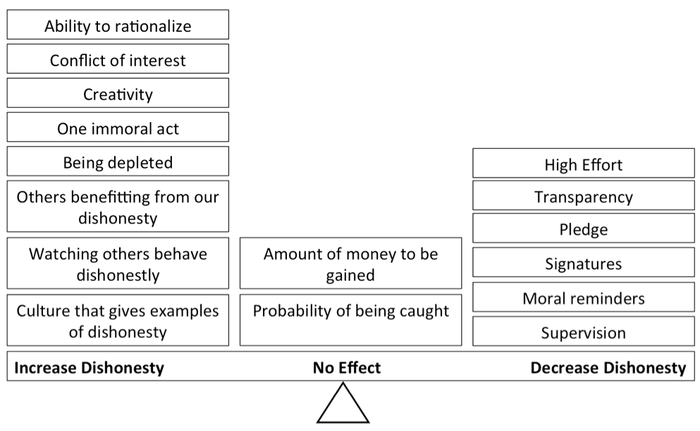

Dan Ariely’s research showed some other elements that had an influence on dishonest behavior. Let’s first look at the ones that increase dishonesty and cheating.

If the players involved have a high ability to rationalize or are very creative, they are more likely to be dishonest at some point. They are more creative and can more easily find rational arguments why their dishonesty is still not dishonest. When the players are set up with conflicting interests, then they basically must cheat to achieve them. As we know from the financial system, short term interests often conflict a lot with long term interests.

If we see immoral behaviors or live in a culture where immoral behaviors are rewarded, then people are more likely to be dishonest. Often one immoral act by the player is enough to justify future immoral behavior.

Interesting enough, altruistic behavior may bring up dishonesty. If somebody else, like people in our tem with whom we have a bond, profits from our dishonesty, we are more likely to cheat for them; even and especially, if we don’t get out anything for ourselves.

And then willpower is an important factor. Willpower is a depletive resource, and when we are at a low level, our willpower may not be sufficient to resist dishonest behavior.

Methods that decrease cheating includes the above mentioned level of transparency. But also reminding people through multiple ways of the morals, laws, and honor codes. But here is the twist: players must be reminded of them before(!) they start playing the system. If you have players pledge (like let them repeat the honor code of the game), or give them a moral reminder (like letting them list the 10 Commandments or similar moral standards), or have them go through a process that requires them to sign to stick to the rules and not cheat, then cheating according to Ariely’s research is remaining at a low level. But it is important that those things are done before(!) they player start interacting with the system.

The last method to be mentioned is supervision. Cheating and dishonest behavior is reduced, if players know that each of their steps is monitored.

In contrast to conventional wisdom, the probability of being caught in the act of cheating or the amount of money that can be gained have no influence in how much people are going to cheat.

The video game world is very familiar with cheating, and while measuring and detecting cheating is never easy, a number of counter-measures to prevent cheating, or make it harder has been developed. Beside gamer etiquettes, PunkBuster, Valve Anti-Cheat, and Warden are some of the many software solutions used by online-games and MMOs to reduce cheating.

To conclude on that topic, be aware and prepared for the following:

People will always try to find ways to cheat

Not all cheating is bad cheating

Anticipate the ways in which this may happen

Make sure you detect and can react swiftly to a cheating pattern to prevent negative impacts on your gamified systems and the honest players

Test your system to detect cheating opportunities early

This article is part of Mario's book Enterprise Gamification - Engaging people by letting them have fun. It was released in July 2014.

This article is part of Mario's book Enterprise Gamification - Engaging people by letting them have fun. It was released in July 2014.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like