Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

My fifth book is starting to take shape, and it's giving me the chance to revisit the topic of Pay to Win Design. For today, I want to discuss the three clear signs that a game is pay to win.

The digital ink hasn’t settled yet on my fourth book, let alone my third, and I’m already planning book five to be on free to play/monetization. With it, the discussion returns to the topics of ethical free to play and everyone’s “favorite” phrase: pay to win. There has been a lot of arguments from developers and consumers over what is and what isn’t, and for today’s post, I want to take on the difficult task of laying down the core arguments for when something is unethical and p2w.

The last decade in the free-to-play space was pretty much about arguing over the use of monetization practices throughout the industry. Gachas, loot boxes, fun pain, gambling, etc., have become an element of a lot of free-to-play games, and even some AAA. Trying to decide if something is ethical free to play is tough because as with a lot about game design, individual mechanics and systems have no allegiance. What could be considered ethical in one game could be malicious in another. There was a point where developers tried, and failed, to justify to me that ARPG design with loot and loot boxes are one in the same.

There is no one perfect thing that automatically makes a game’s monetization ethical or unethical, and we must look at the entirety of the monetization model to render a verdict. With that said, these are three points that I’m going to be talking about in my fifth book, and I feel are three bars that every monetized game needs to clear.

1—Does the consumer feel pressured, forced, or coerced into spending money?

Much of the first and second-generation mobile and free-to-play games were designed to get money through annoyance. This is where the concept of “fun pain” came about and has been a stigma of mobile games for over a decade. I’m sure everyone remembers the Harry Potter mobile game that has a scene where a kid was being strangled while the game asked the player to spend more money to refill their energy.

So much about the unethical side of F2P games is about psychological manipulation of the consumer; whether intentional or not. Having “best purchasing option” or “24-hour limited sale” pressures the consumer into spending money. Games that specifically design their UI to hide or downplay how much money someone is spending is another problem. With that said, there are far more subtle examples of how games can try and convince someone that should be spending.

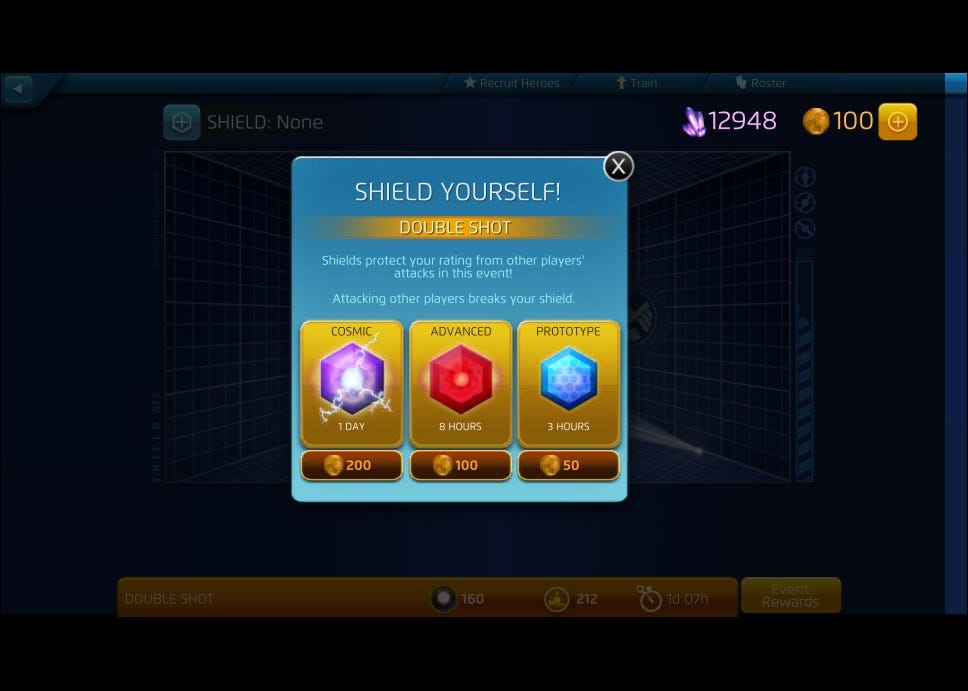

Many F2P games that have competitive modes or alliance modes are designed to punish players (and their guilds) if someone cannot pull their own weight. I spoke about Marvel Strike Force in the past and how their alliance mode also came with PVP-specific characters that not having them often meant the difference of your alliance winning or losing. In fact, competitive games are often the ones that manipulate the player the most. There was the controversy of Activision patenting a matchmaking feature that would purposely put weaker players against paying players so that they would lose and feel the need to spend money.

Manipulating the consumer can be at all levels with monetization

Someone playing a free-to-play game should never feel like the game is being tilted or manipulated to make them spend. There is a big difference between someone wanting to spend money to either support a game or get something in it, and feeling like there is no other way to keep playing unless they spend to gain power. With that said, a lot of these discussions have focused on game-effecting content, but there is another point that must be discussed.

Games that have the bulk of their monetization focused on cosmetics of all kinds. The mobile game Azur Lane is one of the most generous I’ve played when it comes to getting currency for gacha rolls, but all cosmetic skins are expensive and the drop rate for the resources is near impossible to get regularly. A general comment that has been repeated is that if a microtransaction doesn’t provide gameplay advantages then it is perfectly ethical. This next point is well past the time for it to be said:

Cosmetic options that can only be purchased with real money are examples of unethical f2p design. People have been bullied or feel left out, and have been made to feel worse for only using “default” skins, and this has driven a lucrative chase whenever new cosmetics are introduced. We are past the point of arguing about it, and no one should be leaving a comment to try and justify this.

Many of the examples that fit this section are on the subtle side, but the next point is very much overt, and if discovered, is the nail in the coffin for a lot of free-to-play games.

2—Are there any purchases that provide a unique advantage over other players?

Part of the problem with rendering a verdict on any game with monetization elements is that at the end of the day the developer needs to be earning money to justify keeping the game going. A free-to-play with no microtransactions or monetization model is one that is not going to be able to maintain its livelihood for long.

Being able to spend money to see more of the game faster, or get something you really want is fine…to a point. One of the easiest ways to spot a pay to win game is if there are any microtransactions that give a paying player an advantage that cannot be acquired otherwise. Many mobile games have used what is called a “VIP system” as a way of getting players to spend money. The concept is that the more someone spends, the more advantages they unlock as their VIP level goes up. This can include getting more inventory space, more free currency, or even making game systems easier to use. Any time a microtransaction can make a game easier to play, or reduce fun pain, would fit into this category.

Illusion Connect’s Gacha system locks many of its characters to banners only

If there is a character or weapon that can only be earned by spending money, that falls into this category. One of the more grey area systems that has risen in popularity is the “battle pass” or season system. How it works is that during a specific season, players can earn rewards by playing the game and completing objectives. By spending more money, players get an upgraded battle pass that features unique rewards as well as just having more for doing the same amount of playing. If there is content exclusive to the paying battle pass version, I feel it would fall into this category. If both free and paying players can earn the content, with paying players getting it earlier, then I feel that would be an acceptable tradeoff.

No matter what, when you have a game built off continued monetization, someone who spends money is going to have an advantage. But for my final point, the question turns to how much of an advantage is there to spending money?

3—Is it possible to progress/compete without spending any money?

One of the specters that has haunt free-to-play games since the early 00’s is balancing a game for both free and paying players. There are two specific points for this question:

Can someone use skill to win over someone who spends money?

Is it possible to progress at a comparative rate to a paying player without spending money?

RPG-based design that uses free-to-play elements typically favors abstraction over player skill. If you are the best player in the game, but you don’t have the best characters or the highest-ranked ones, then there will be a hard stop point for how far you can progress. Character hunting in a lot of gacha games isn’t just about getting the best character, but being able to upgrade them to their max power; oftentimes requiring multiple copies or “shards” of said character.

For ccgs, this is not as bad depending on how the booster packs are being designed, as cards can’t be “powered up.” However, many longstanding CCGs run into problems when it comes to introducing new content. While you will never see good CCGs up the power curve with new cards, that doesn’t mean that newer cards aren’t superior to older ones. Hearthstone has had a longstanding issue with balance in this regard, as there is no competitive reason to ever use the base decks when you have years of booster packs, expansions, and game-altering cards introduced. I still remembered my early experience with Hearthstone and running into someone who every other turn was throwing down a legendary card compared to my starter deck at similar rank, I can’t imagine how bad it is now starting fresh. For skill-focused games, like shooters and fighting, spending money may offer some advantage of having more characters or weapons available, but these are genres where skill will always trump spending.

However, the other point is far trickier to pin down. There have been plenty of free-to-play games that give the player free currency or allow them to unlock things without spending money, but there is more to this than just free stuff. A very popular monetization tactic is to let free players “earn” the resources they need to progress, but at such a slow rate that it’s almost not even worth it. When I spoke to Ramin Shokrizade on several occasions, his view on when a game becomes pay-to-win is if a paying player can supersede the progress or time spent needed to play the game. What that means is if someone pays money and can complete the same task that could take someone hours, or even weeks and months to complete, then that is pay-to-win regardless of the free option. For Honor got a lot of flak in its first year with requiring free players to play daily for over a year to have any chance of unlocking all the content that was in the base version.

Marvel Strike Force once again has a very nefarious system that fits here. Many of the best characters in the game are tied to limited-time events that require set characters or classes to be almost at max rank to unlock them. What they have done in the past is set the required characters to the newest ones, making it literally impossible for free players regardless of their accounts and skills to unlock these characters on their first appearance. This gives paying players several months of being the only people who can access these new top tier characters.

Being competitive in free to play games is often about constant spending to stay ahead of everyone else

Besides multiplayer games, we can also talk about the issue in single-player or player vs. AI content. If a paid-only, or low drop rate character, can dramatically change the difficulty and rate of progress in a campaign, then the game is pay-to-win. That last sentence is important, as many people will only associate these topics to multiplayer-focused games, but we have seen AAA developers slow the progression curve or make things frustrating unless the player buys in-game microtransactions; such as with Shadow of War and some of the Assassin’s Creed games.

People can argue that you can make progress with free accounts and not the best characters, such as in Genshin Impact, but you can see very clearly just how much of a bump an account can get in these games by getting a five star or early SSR/UR (Super Super Rare, Ultra Rare) character. In fact, many guides for these games will specifically point out what characters to get with the new player special banner and to reroll if you don’t get them.

Monetization is an essential part of any free-to-play or live service game, as without it, no title would survive long. But doing things right requires a commitment and focus from as early in the game’s development as possible. Far too many mobile and free-to-play games were monetized to get as much money as quickly as they could, and this “scorched earth” method has cause a lot of people to swear off of playing these games.

If you want people to stick around long enough to be willing to pay, you need to put out a great product and game first. In today’s market, trying to hustle or force people to spend money in your game is not going to do well, there are far too many alternatives out there.

Good free-to-play design needs to balance the needs of bringing in income with the need of providing great content to your player base. Hoping and pleading for whales to finance your game above all else will lead to a doomed product. The free-to-play games that want to survive the long term need to always be thinking about how they’re going to keep growing while bringing income in.

What are your thoughts on P2W Design? Are there any details I missed when it comes to defining it or major examples? If you’re interested in more of my thoughts on the topic, Game Design Deep Dive F2P will be coming sometime in 2022.

If you enjoyed my post, consider joining the Game-Wisdom discord channel open to everyone.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like