Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Extracted from their SIG Video Game Journal analyst newsletter, Jason Kraft and Chris Kwak look at the arguments surrounding episodic gaming and weigh the advantages and disadvantages, in the hope of simplifying the debate for investors heading into E3.

April 18, 2006

Author: by Chris Kwak

[This article was written by Jason Kraft and Chris Kwak of the Susquehanna Financial Group, and is extracted from their regular SIG Video Game Journal analyst newsletter. You can contact them to request copies of the SIG Video Game Journal via email at [email protected].]

Back at Game Developers Conference (GDC) 2000, Phil Harrison, Sony Computer Entertainment Worldwide Studios President, highlighted episodic games as a promise of the PS2. Launching Xbox in 2001 and Xbox Live in 2002, Microsoft told us: “[Xbox has a HDD] for storing episodic content delivery,” among other things. At GDC 2006, Phil Harrison seemingly echoed, “Episodic content! I'm personally very excited by that. I believe games can have the same social currency as a great TV program.” During this period, Valve has turned up the Steam engine – a digital download/delivery system for games and episodic content on PCs. Services such as GameTap have focused on classic arcade-like games and casual games. And now everyone is talking about episodic games.

What is an “episodic game?” And why do we care? Simplistically, episodic gaming is more relevant in the digital distribution age. (Breaking a 20-hour game into five episodes to be packaged five times in five DVDs and transported and distributed five times is an unappetizing thought.) As investors, we generally focus on revenue growth drivers and margin expansion factors. This is why we're interested in portables, wireless, in-game advertising, and micro-transactions. All of these opportunities also offer higher margins. However, we are as interested in minimizing risk as we are in maximizing reward. Is it any surprise then to find the video game industry looking to take more risk out of the game creation process? The purpose of this report is to define “episodic gaming,” to consider the arguments, and ultimately to weigh benefits and the costs to publishers.

Development vs. Distribution vs. Consumption

We begin with a handful of definitions. The following terms can mean one thing to a developer, another to a publisher, and something else to a consumer. Because of the numerous definitions and intent of these terms, we are delineating clear meanings for the purpose of this report only. Note: We are not arguing that these are “the” only definitions.

AAA. Today, games are generally developed and published as complete entities sold at retail. These games are packaged and sold to consumers at varying prices. For simplicity, we define complete games purchased at retail as AAA, whether they are $60, $50, or $30.

Expansion pack. Some AAA titles can be extended with expansion packs (downloadable or packaged). These packs can be new installments and can retail at close to AAA prices. Others can be merely extensions of a game and cost a fraction of the AAA title. Halo 2 Map Pack at $20 is such an instance. The PC market has been releasing expansion packs to games for years. Consoles have rarely capitalized on a successful AAA title with an expansion pack. Publishers have opted for sequels.

Sequel. Typically, when a AAA title sells well, the publisher may decide to leverage the investment and work on a sequel. The sequel is typically the same price, and the scope of the original and the sequel will be similar. We are used to sequels in console games just as with movies.

Episodic game. A quick search for “episodic games” will return many definitions. Some argue that an episodic game is defined by a development structure; others argue it is typified by a delivery/distribution schedule; others argue an episodic game is a different method of storytelling; and, still others define episodic as a change in game consumption.

Clearly, all of these views are relevant in defining episodic games. We have to ask what the purpose is of calling a game episodic. If the argument is that developing games in pieces (episodes) is cost effective and levels the playing field for smaller developers who do not have budgets to compete against the big houses, then episodic might refer to the intervallic development structure of a game and the management of risk. If the argument is that games (in a networked world) could be delivered in episodes, like a TV series, then episodic probably refers to the distribution of games in pieces as chapters of a story. If the argument is that games should provide manageable blocks to consumers who dedicate a limited time to playing them, then episodic games focus on game consumption.

We do not believe the distribution methodology defines episodic gaming. That is a function of slicing a story (and the many adjustments this demands) and distributing it to consumers and drawing them in (often via a subscription). We do not believe consuming a game in bite-sized chunks of time defines episodic gaming either. It is our contention here that we already consume games episodically. Simplistically, complete games are structured to be played episodically. That's what the Save and Save and Quit options do for gamers. Episodes are bite-sized mini-games or slices of a whole. But aren't the “The Silent Cartographer” in Halo and “Battle of Stalingrad” in Call of Duty 2 also episodes? Escaping the dungeon in Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion felt like a three hour episode. (The giant rats are just dreadful.) One could argue that episodic gaming (generically) has been a mainstay of certain types of PC games (The Sims and MMOGs). Every new release of Madden, NBA 2K, World Soccer Winning Eleven – is a new episode (season) of a game (sport) that persists.

Delivering chunks of a completed game in intervals can be done (with some modification), and consuming a game in edible bytes is arguably done already.

For these reasons, we are not focusing on the delivery and consumption of a game as the defining attributes.

We define episodic games as the development and production of a game in parts – releasing a finished portion while developing parts (that complete a single story arc) that have not been coded. Episodic gaming as a development strategy is rather new. It has become more plausible because of digital distribution. We are therefore interested principally in the episodic development of games for the purpose of this report.

Why the Buzz about Episodic Gaming, Now, Again?

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (by Bethesda Softworks in conjunction with Take-Two's 2K Games) has shipped 1.7 million copies since its release last month. Oblivion is already a smashing success – all the more impressive given the absence of versions for current-gen consoles. As developers and publishers bet on next-gen games, they will want to repeat the success of Oblivion.

But what if Oblivion had gotten a cold reception? (The lone new IP bet for the Xbox 360 launch (Activision's Gun) was admittedly disappointing at retail.) Oblivion took four years to develop in a labor of love by Bethesda. Without details about the cost of developing the game, we can say with some certainty that the game looks expensive. [The non-player characters (NPCs) are sophisticated enough to make us pause about our view on AI.] The Bethesda team began developing the game in 2002, and after some delay, the game hit retail shelves on March 20, 2006. Four years! A failure at retail is painful to contemplate: four years and millions of dollars is a lot of risk to take on a single game.

Many of us who have played Oblivion winced at the potential for extemporaneous gaming in the RPG that could last 30-40-50 hours. For many of us, 50 hours of anything is probably too much. The psychological impact of this potential covenant with the game can be Sisyphean. As a person with a few hours on the weekend (and fewer hours during the weekday), purchasing and playing Oblivion demands commitment. Hence, we exited the catacombs, dumped the rat meat, and were glad we had reached the surface. We haven't touched the game since.

Our age is one of aging. Mainstream gamers are now older on average than they have ever been. When you are single and unemployed, it is easy to play The Godfather for nine straight hours the day the game hits the shelf. When you are married, it becomes tougher. When you have kids, it might be impossible.

It is difficult to slice some time for yourself. And in that slice, you have to carve a portion for gaming. It is no wonder casual games that require no more than 10 minutes to play continue to grow in popularity. This is why we are more likely to login to Call of Duty 2 on Xbox Live to play a quick five-minute Team Deathmatch and leave the Lobby. For many, we are approaching an era of staccato gaming – an intermittent gaming life where fragments of game experiences cohere to fulfill a story. These game experiences can be discontinuous, sporadic, disconnected even (for example, a Deathmatch), casual, scattered, sometimes seasonal. In other words, these game experiences become episodic – often not as a function of a game's story arc and structure, but what frees and steals our time.

In the past five years, we have observed a phenomenon in television that many find relevant to video game development and production. On television, the success of TV shows like 24, which plays out each episode as an hour in the life of protagonist, Jack Bauer, has inspired game developers to look at constructing and releasing games as episodes. The working assumption appears to be that some games/genres are stories that can be broken into episodes, like 24. If this is true, then a development team could test – and a consumer could try – an episode before going “all-in.”

At first, we were intrigued by the idea of episodic game development. If those promising cheaper development via smaller episodes of games could deliver, would everyone push for this? As our base, we start with a standard AAA game as developed, priced, and sold today.

Scenario Models

Figure 1 depicts sales data of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, released November 2004 by Konami, up to the present, March 2006. Historical units, ASP, and revenue figures are all actuals. All margin estimates are SFG.

In the AAA model, games are completed (start to finish), released once via retail, marketed once, priced at AAA levels ($50), and in the first year, the majority of consumers will purchase the game in the first 3 months, after which, there could be a two-year wait for the sequel. In this standard game development scenario, costs are absorbed “up front” and revenue is derived immediately.

Most people assume episodic game development is a better model in terms of cost. What are the assumptions that underlie this view? The basic argument goes something like this: “Sink $20 mln and three years into a video game that flops. What a waste. There's got to be a better way.” Let's look at what an episodic development model could look like for a game with three episodes.

Most people assume episodic game development is a better model in terms of cost. What are the assumptions that underlie this view? The basic argument goes something like this: “Sink $20 mln and three years into a video game that flops. What a waste. There's got to be a better way.” Let's look at what an episodic development model could look like for a game with three episodes.

In this scenario, development cost is distributed (although not evenly) across many game units. The release schedule is every four months, and the price per episode and the time commitment to complete one are fractionally distributed, as well. [Note the digital distribution element of the model. While this is not currently the way console games are delivered, we are factoring digital distribution into the model because it will be possible.] Does the episodic development model mitigate the AAA development model of today? Does the episodic model resolve the issues that its proponents claim? We don't think so.

In Figure 3, we assume subsequent episodes attract smaller audiences. We have observed roughly 50% to 60% attach for successful PC expansion packs. In order to normalize the episodic model with the AAA model, we model these episodes over 24 months.

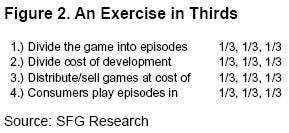

In Figure 2, An Exercise in Thirds, above, we list four factors that highlight general assumptions, expectations, and conclusions of episodic content. We believe each is problematic. We take them in order.

1.) Divide game into episodes of 1/3, 1/3, 1/3. Are games divisible, like TV's 24 or a comic book series? One could argue that games are stories by nature and that the history of gaming would have been episodic if broadband consumer Internet started in the 1980s. This is unlike movies historically, where we had to go to the theater. If digital distribution of movies grows in popularity, should we assume that movies will become episodic? We could wax aesthetic about what forms of entertainment and art are divisible. Or ask, “What can we divide?” We jump to the chase instead and ask, “Would anyone want to divide a FPS?” A Racing game? How about Sports? Is TV (and 24 in particular) the right analogy? One could argue that episode one of a video game is like the pilot (or first four episodes) of a TV show. TV shows have smaller development cycles. Soap operas, game shows, and news channels are examples. A TV series can produce an episode quickly (days vs. weeks; weeks vs. months; months vs. years). TV can be flexible. If there is a missed line, one can improvise; if the camera angle or lighting isn't perfect, ok; if it's a bit hard to hear, that's forgivable too. If a game has one serious bug, it could be over.

2.) Divide cost of development by roughly 1/3, 1/3, 1/3. Why do we believe a game developed in three episodes costs fractionally as much? Is it merely because a third of the content should be a third of the cost? Let us ask the question: If a studio invests nine months on a AAA title versus six months before the projected is canceled, would we conclude the nine months is a 50% bigger write-off than the six months? Games, like movies, have lots of assets that need to be established pre-development (production teams, sets, equipment, tools, software assets, story line, architecture, actors, etc.). There is an amortization schedule for these investments. We are not even factoring the potentially higher variable costs of episodic game development. Unlike AAA game development, episodic games require quality assurance and testing for each episode. Never mind the episodic marketing cost for each deliverable. The larger issue is whether episodic games are more profitable. Creating a third of a game will likely cost less than a whole game. However, do the profits exceed or even match a AAA title? If a AAA title that requires 24 months and $15 mln fails, is it any worse than three failed attempts at episode 1 of three different games, each requiring eight months and $6 mln?

3.) Distribute games at cost of 1/3, 1/3, 1/3. Is a third of the content at a third of the price equally attractive to a consumer? Many argue that the lower price point per episode could increase the audience opportunity. Sounds reasonable enough. On the face of it, this is like saying Cabela's at $20 should potentially have a greater audience than GTA because $20 is less than $50. What must be implicit in these kinds of arguments is that the content is held constant, that the experience of consuming episodes in aggregate will yield at least the utility of consuming a AAA title at once. It is difficult to prove that this episodic pricing model will yield the same economic return of the traditional AAA pricing model. So far, we have seen no evidence.

4.) Consumers can consume byte-sized 1/3, 1/3, 1/3. One of the key drivers of the episodic game model is the belief that consumers do not want to consume 20 hours of games, that we want someone to break this into episodes for us. We ask, is a third of a movie at a third of the price equally attractive? How about a third of a newspaper at a third of the price? If you get 100% of something at 1/x price, then yes it is more attractive. What if you get 200% of something at 100% of the price? How about 300%? When it's a consumable that is not perishable, maybe. But when it's time, is this necessarily true? Let's do a thought experiment. More for less? Two hour movie at $10. Three hour movie at $10 just better? How about a four hour movie for $10? A one hour movie at $10…if it's good, I don't mind. Look at Rush Hour 2 (90 minutes). There's a curve.

Our View and Preference

If publishers continue to favor and build AAA titles – and we believe they will on the console – we hope they will develop games with expansion packs in mind, online-enabled with micro-transaction capabilities. We are not surprised to hear that Microsoft is encouraging publishers to factor expansion packs to be released after AAA games release to retail.

Who Does This Benefit, Really? Power Struggle for Economics

When we purchase Call of Duty 2, the retailer, console OEM, and the publisher (and developers) share in the revenue. When we play Call of Duty 2 on Xbox Live, we pay Microsoft $50 per year. That's it. The traditional retailer gets nothing; neither does the publisher, and certainly not the developers.

Who is pushing episodic content? Valve is pushing it. Why? Sony is pushing it. Why? Many developers are pushing it. Why? Without getting too dramatic, we believe what we are witnessing in the episodic game debate is a battle for market share – for now, between PC and console – via a new distribution method in light of the success of MMOGs and XBLive. We believe it is less about the big guy vs. the small guy, or the mitigation of risk in the face of escalating development cost. It is about controlling the subscription model for gaming.

Software as a Service (SaaS) has become a buzzphrase since salesforce.com came public. Everyone is looking to SaaS. At the heart of the debate about episodic gaming, we believe there is a push toward Gaming as a Service (GaaS, an unfortunate acronym of sorts). Subscription-based video game consumption via digital distribution appears to be one of those paradigmatic shifts that could dramatically and permanently alter which side gets how much in the foreseeable future. Much of this will come at the expense of traditional retailers.

Food for Thought

In the 1980s, the video game dollars went to the console manufacturers who also typically were the game developers. In the ‘90s, we witnessed the growing power of the third-party publishers. In the current-gen cycle of the past five years, we saw the content owners (Marvel, NFL, Pixar, etc.) take share of the gaming pie from the publishers. Going forward, there may be a limit to the size of the console gaming pie. As a consequence, subscription-based services will probably be a significant opportunity to lock in consumers and to generate new revenue streams. Who will succeed in capturing share in this growing pie? As always, the PC guys are firing first. We can hear the footsteps of the console guys, however. Publishers will have to decide which model is more beneficial for them. Identifying friend versus foe in this battle will be their first task.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like