Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"In my take on realism, I like to take that reality of something, and provide my twist."

A few months ago, Deadly Premonition and D4 creator Hidetaka "Swery" Suehiro struck out on his own with the launch of White Owls, an independent game company that announced its first game The Good Life a few weeks ago. The campaign has achieved 19 percent of it's $1.5 million goal, with nine days left to go.

Since Suehiro's joining a wave of Japanese developers willing to embrace crowdfunding and indie development, and is setting up a unique business relationship with the Japanese studio Grounding Inc, we wanted to catch up with Swery and ask about how life has changed for him since leaving Access Games.

After preaching the gospel of Sweryism to a crowded hall at PAX, Suehiro (joined by Grounding COO Yukio Futatsugi) took some time to talk to us about his design philosophy for The Good Life, and what’s changed about going independent.

If you happened to catch Suehiro's PAX talk, you might have scratched your head when he mentions that he enjoys putting “realism” in his games. If you’ve played Deadly Premonition or D4: Dark Dreams Don’t Die, you’re probably aware those games aren’t what we call “realistic.”

When pressed on this, Suehiro makes a delineation between photorealism and the realism he thinks about when designing his games. “When I think about my sense of realism, I think of a word like 'deformation,’” he says via translator. “Which is taking a real feeling that people get when they see something, and picking apart the elements that are exciting to them.”

Suehiro uses the example of the unusually long table from one notable scene in Deadly Premonition to explain this philosophy. “In real life, that table was long, but maybe not that long. But in my take on realism, I like to take that reality of it, and provide my twist by doubling or tripling the size of that table.”

Trailer for the unique Deadly Premonition

"In my take on realism, I like to take the reality of something, and provide my twist."

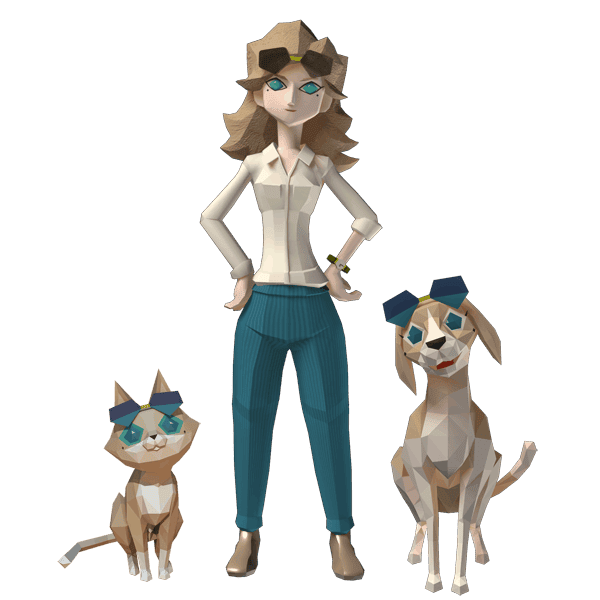

It’s a view on realism that extends to The Good Life’s central premise, which is about a photographer trapped in the English countryside, in a town where people turn into cats (and dogs) at night. It turns out Suehiro's been thinking about a game where the player is trapped in England for a while, ever since a producer he worked with was “trapped” in the United Kingdom in 2008.

“Around 2008, while working on [Deadly Premonition]…we had a producer who was sent to England as part of work, for 3 months, to do a remote work in England. [That] ended up turning into 4 years in England, and not being able to come home because of work-related issues."

“I remember thinking 'what would it be like to be stuck in England for that amount of time?' Maybe that's where some of the initial ideas came from.”

(Fun fact, if Suehiro making a game about solving a murder in the European countryside sounds familiar, that’s because, according to an interview with Suehiro by Matthew Kumar in 2011, it was almost the foundation of Deadly Premonition.)

When Suehiro introduced The Good Life to the audience at PAX (while making jokes about how everyone knew about it because of an unanticipated leak), he also announced that the game would be a partnership between White Owls and Grounding, with help from Ryan Payton of Camouflaj.

While game companies often work with outside companies to make a game, this separation of a game’s creative core and its development team is slightly unusual. But, as Suehiro and Futatsugi put it, it’s the perfect arrangement for two drinking buddies with similar taste in odd games. “When it comes to White Owls…we haven’t had time to build the team up until now,” says Suehiro. “So I’ve been thinking about how I Can partner with an experienced group of folks that I can trust, and somebody that came to mind after many nights of drinking together was Futatsugi.”

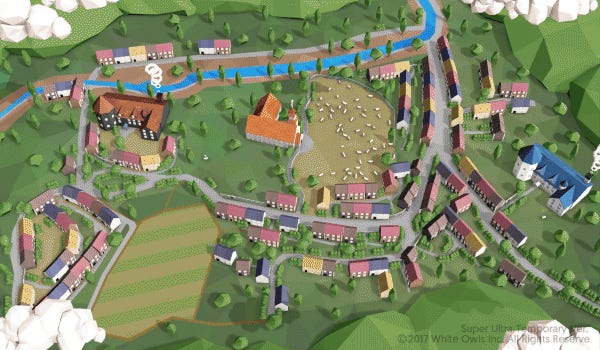

The small-town setting of The Good Life

Futatsugi, who created the Panzer Dragoon series, says this relationship is unusual but possible when both creators are on the same page. “When I think about this new arrangement, I think about the possibilities of what two or medium-sized companies can do when they come together and try to make a triple-A title.”

Both Suehiro and Futatsugi say that crowdfunding is new for them, and that the biggest difference will be actually getting to make a game using the money of the people who will play it, as opposed to publishers or clients they’ve worked with in the past. Futatsugi says under those conditions, “the sense of responsibility is so much higher, and the pressure and sense of responsibility to create something wonderful is even greater.”

One recurring theme in criticism of Suehiro's prior games (which he embraces and admits to in conversation), is that for all their uniqueness, sometimes the way his games play can feel unpolished or rough. Ten years ago, when publishing for consoles, that could be fatal to a game’s success. Now, developers can make millions in Early Access with unpolished titles that break and crash.

Suehiro laughs a little too long when quizzed about this discrepancy. But in response, he reflects on how the Japanese game industry tends to focus on bugs and how that’s changing with the status quo.

“The Japanese game industry has been very focused on highly polished console games and the legacy of console games has been that games are developed, and a team worked hard to eliminate as many bugs as they can before it goes in front of the publishers or the platform holders. “The commercial success of the game is often times spoken about in the context of how polished or how bug-free the game might be."

“In more recent years with the rise of Early Access and PC games, Japanese game developers may not be experimenting with this as much as maybe we would like to, but the Japanese developers are starting to understand and see this more that it's more of a dialogue directly with users, that when you put a little bit of content out, and even if it's buggy, the user responds positively to you. That's a level of feedback that Japanese developers have not received up until now.”

Futatsugi also sees promise in releasing unpolished features based on his experience with smartphone games, since he believes there’s an audience who’s willing to accommodate a certain roughness in exchange for new experiences. “It’s a very common thing in that side of the industry in terms for quick updates, and getting the game experience up to the quality that all users would like, and I believe that's part of the process that users believe they're growing with the game, and part of that whole process,” says Futatsugi.

For more details on The Good Life, be sure to check out the game’s crowdfunding campaign over on Fig.

You May Also Like