Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How the irrational way we treat “free” as a price in games can lead us astray …or keep us on track.

[Jamie Madigan writes about psychology and video games at www.psychologyofgames.com. Consider supporting him on Patreon.]

Luca Redwood is a UK-based game developer who in 2012 scored a mobile game hit with an awkwardly named match 3 role-playing game, 10000000. Recently he released its sequel, You Must Build a Boat. Between those two games, though, Redwood released a peculiar dueling game called Smarter Than You. It's like rock paper scissors in that sword beats arrow, arrow beats counter, and counter beats sword. But you can also bluff before each attack by using a menu of words to build sentences. You could say "Arrow looks like a good choice," but you don't have to take your own advice. You could hope to throw your opponent off and choose counter instead.

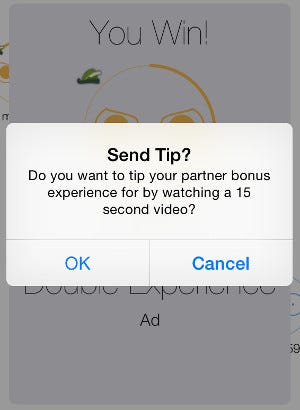

But what really interests me about Smarter Than You is what happens at the end of a match: you can give your opponent a tip.

The game features an experience point and leveling system, which unlocks cosmetic options. Besides winning matches, you can also receive experience as a gift from an opponent. But here's the weird part: Tips were originally done only through in-app purchases. After a match, a little slot machine wheel would spin and you randomly got the option of paying either $1, $2, or $3 to give your opponent some bonus experience points. You could choose not to tip at all, but if you did tip it cost YOU real money to give THEM bonus experience points and YOU got nothing out of it but warm fuzzies.

Weird, right? You'd not be alone to think so. I contacted Redwood and asked how many people tipped using this system. "For me at least this was the big surprise," he said. "People paying real money to give their partner a bonus doesn’t happen often. I think I’ve had a total of 2,000 to 3,000 paid tips, While it's amazing to think that those people paid real money to benefit their partner, out of millions of games, it’s a very small percentage."

Well, in actuality it's beyond "very small" if millions of games were played. It's essentially 0.00% after you round off.

Generosity wasn't much of a money maker. Then about a week after launching the game, Redwood got an idea: What if people could exchange something that's free --their time-- for a tip instead? Watching a 15 second commercial is a common monetization tactic for free to play games because it's a way to get something out of those without credit cards. Kids, for example. "I had the player play a virtual version of me for the tutorial," says Redwood. "After they beat me they could tweet at me to brag. The game had millions of downloads, so I got thousands of these tweets, and a lot of them were younger kids, 8-15 who I figured wouldn’t have a credit card and couldn’t join in the "tipping" game even if they wanted to."

So Redwood added a fourth possible outcome to the slot machine reel: watch an ad. If you get that option and choose it, you watch an advertisement, and your opponent gets the benefit. What's more, they don't even know if you watched an ad or paid real money. This worked out much better for everyone involved: according to Redwood, the percentage of tippers went from 0.00% to 60%. That's a huge increase --far more than you would expect from a linear relationship between cost and benefit.

So instead of paying real money for virtual currency or some other in-game benefit, any player could now watch a video that some advertiser paid Redwood to put in. It was like the players are being paid for their attention.

This lines up with some other research I've read about the irrational way we treat zero as a price --that is, how we treat "free." In 2007, Kristina Shampanier, Nina Mazar, and Dan Ariely published a study in Marketing Science that may shed some light on why the "watch ad" option in Redwood's game might have been so popular. Consider this question, which the researchers posed to some participants:

Would you rather...

Buy a $20 Amazon.com gift card for $8 OR

Buy a $10 Amazon.com gift card for $1

A bargain either way, but most people (64%) chose to pay $8 for the $20 gift card because it netted them $12 in credit ($20 minus $8) whereas the other option only got them $9.

But then they dropped the price of both gift cards by $1 and asked the revised question:

Buy a $20 Amazon.com gift card for $7 OR

Get a $10 Amazon.com gift card for free

For a group of completely rational humans, this should have changed nothing. Because the price of each option had changed the same amount, the ratio of cost to value was unchanged and the $20 card was still the better value. But we evaluate "free" according to different rules than other prices, so every single person (100%) in the study took the free gift card even though it netted them less Amazon credit.

As another example of how this works, let's fast travel to Argentina. In an attempt at reducing litter and waste, a few years ago Buenos Ares began charging the equivalent of 2.5 cents in taxes for using plastic grocery bags supplied by the store. Or you could bring your own bags and pay no fee. Because the rule was phased in, it provided an opportunity for a natural experiment where researchers compared behavior at stores with and without the fee.

The results were pretty clear: up to 90% of shoppers helped themselves to the plastic bags at stores where the fee hadn't yet been implemented, but that dropped to 40% at stores where the bags cost a mere 2.5 cents. Again, the preference for "free" was disproportionate and alluring.

And so I think it is with free tipping (by watching an ad) in Smarter Than You. You could choose just not to tip, but since you do (presumably) get some utility out of tipping in the form of satisfaction and warm fuzzies, the free option is far more tempting than the cheap $1 option. In fact, I think it would will outperform a paid option even if Redwood were able to charge only 1 cent for tipping. In fact, in the spirit of further experimentation I suggested to Redwood that he try this setup:

Incorporate virtual currency into Smarter Than You that you can use to tip instead of real money. Sell, say, 100 purple diamonds for $1. Then instead of randomizing options, randomly split the players into two groups and give each three choices of how to tip. Group A, would get these choices:

Pay 15 purple diamonds and award 1,000 experience points to your opponent

Pay 1 purple diamond and award 100 experience points

Don't tip at all

Then, give Group B these options:

Pay 14 purple diamonds coins and award 1,000 experience points to your opponent

Watch ad and award 100 experience points

Don't tip at all

If the Shampanier, Mazar, and Ariely study is any indication, most people in Group A will spend 15 diamonds to award 1,000 points, but most people in Group B will be irrational and elect to watch the ad. But what would be interesting to find out is if the options in Group B generated more tipping (and more revenue) overall because of those choices.

Somebody get on that.

[Jamie Madigan writes about psychology and video games at www.psychologyofgames.com. Consider supporting him on Patreon.]

CITATIONS

Jakovcevic, A., Steg, L., Mazzeo, N., Caballero, R., Franco, P., Putrino, N., & Favara, J. (2014). Charges for Plastic Bags: Motivational and Behavioral Effects. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 372–380.

Shampanier, K., Mazar, N., & Ariely, D. (2007). Zero as a Special Price: The True Value of Free Products. Marketing Science, 26(6), 742–757.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like