Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest column for Gamasutra, veteran game lawyer Buscaglia discusses developer and publisher contract negotiation shenanigans - urging an 'eyes open' attitude from the developer end.

[In his latest Game Law column for Gamasutra, veteran lawyer Buscaglia discusses how developers should work with publishers on a contract for your game - urging active, intelligent negotiation at all times.]

The proper negotiation of a contract is a process that is too often ignored by developers, especially those eager to get a deal. I suspect that part of the reason for this is that the stereotypical game maker neither likes nor enjoys the process.

The harsh reality is that many, if not most, publishers are so used to developers being passive about the negotiation process that they have become arrogant and unwilling to actually engage in a meaningful negotiation dialog with developers.

Instead, they too often become rigid and inflexible when it comes to their contract negotiations. And I suppose this attitude comes in part from, among others, the following factors:

An overwhelming financial advantage held by publishers in the relationship

Publisher risk aversion

The perception, at least, that there are more developers than deals

A failure by developers to have or communicate a long term vision for their studio

A lack of appreciation of the "process" of contract negotiation

Developer fear, rather than appreciation, of being exploited

These factors are certainly not present in every deal dynamic, nor do they apply to every publisher or developer.

Moreover, with the vast array of innovative approaches to succeeding in the industry, even the traditional developer-publisher model is hardly a standard for the way we do business.

However, there may be some value to just accepting the stereotyping for the moment and proceeding with the discussion to see where it takes us and what we can learn in the process... so, shall we proceed?

Sure, the publisher has the money. And lots of it. And the developer needs the money to make the game and build their studio. What possible leverage can the developer have in a situation like that?

Sure, the publisher has the money. And lots of it. And the developer needs the money to make the game and build their studio. What possible leverage can the developer have in a situation like that?

Well if you look at it like that, it may actually make sense to take whatever deal the publisher offers and just "take your beating like a man." But, I don't think so.

Step back a little and consider what it is that the publisher sells... games. And what does the developer have that the publisher does not?

A game. And all the money in the world is useless to a publisher if they have no games to sell -- unless they want to open up a bank.

Oh yes, they want and need your game. If they didn't, they would not be talking to you. The old Steve Miller song, "Your Cash Ain't Nothin' but Trash" comes to mind.

So, while the developer may desperately need to dollars, the publisher needs the games. I sense the makings of a mutually beneficial business relationship.

Publishers, as businesspeople, focus a great deal of attention on risk avoidance. They sometimes even use it as an excuse to convince developers to accept terms in a deal that are, in reality, unnecessary or overreaching.

In a deal with a developer the easiest way for the publisher to minimize risk is to put as much risk as possible on the developer. So, back-end loaded budgets, long payment procedures and the necessity of the publisher owning the IP is standard "policy" for many publishers.

Well, as a professional negotiator, I'll tell you what I hear when someone says "it's policy" or "it's the standard deal in the industry." I hear nothing.

If the publisher cannot provide a realistic logic-based justification for an adverse contract provision, make them or don't agree to it. And if the best they can come up with is "reduction of our risk" be extremely skeptical.

I recently ran into a really clever ploy by publishers. In order to overcome the objection to IP assignment for original IP games, instead of demanding the IP ownership in the deal, publishers are now allowing the developers to retain IP ownership until after the game is released.

However, the publisher retains an option to buy out the IP (and in the process the developer's rights to a back-end royalty in the process) if the game performs above a certain level.

What level, you ask? Well, it is inevitably some time before the advance recoup point when back-end royalties would normally kick in if the game is a hit! You really have to admire their guile.

If the game sucks, the developer can keep the IP. But if the game is a hit, the publisher owns it and the developer gets screwed out of any back-end royalties in the process!

There is certainly a perception that there are more developers and games than there are available deals. There certainly are.

However, that does not apply to the right game at the right time. Each game is in many ways unique and if you are lucky enough to garner the interest of a publisher you can rest assured that they believe that your game will succeed.

It could be unique gameplay, your team's reputation in the industry or filling the right slot in the publisher's portfolio strategy. But regardless of why they want your game, once you pass that threshold, you no longer have one of the many games in the marketplace, you have the game that the publisher desires.

And, as I already stated, getting the right games to publish is the whole point of the exercise for the publisher in order to insure their ongoing success.

So, what does having a long-term vision for your studio have to do with your negotiations? Initially, the impression the studio makes on the publisher can make a significant impact on the course of the negotiations.

Conveying a coherent vision can instill a sense of competence in the mind of your contact at the publisher -- that the developers are serious-minded about the long term success of their business, not just their current game. This level of respect will usually have a positive impact on the process.

Also, having a long term vision for the studio can impact the sort of deal that will ultimately be acceptable to the studio.

After all, taking a deal that does not provide sufficient revenue for the studio to survive the development process and stay healthy in the post-release period is important, especially if the long term goal is to build a great studio, not just to make a great game -- which should be the long-term goal of every studio.

A negotiation for a deal is a process, not an event. Developers too often look at the initial offer as the end, not the beginning, of the process. But think about it. Would you expect the initial offer to be the best deal? Certainly not.

In fact, the initial offer is usually the best deal that the publisher thinks they can get. But it is sure not the best deal the developer can secure. In fact, it is often a bad deal for the studio.

Of course, it is gratifying to get any offer, any offer, to get your game made. And it is usually the result of a long period of effort by the developer to get a deal.

But that alone does not make but it a deal with taking. After all, sometimes the best alternative to a negotiated deal is no deal at all.

Naturally, getting a deal is the point. But some extra time, thought and perseverance can make a significant impact on the result.

And don't think that you are going to offend the publisher by working them a little. They negotiate deals all the time -- much more than developers do. They will generally look at it as an expected course of action.

My initial response to a first offer is to respond with the studio's best possible deal. After all, the publisher just probably sent the studio the publisher's dream deal -- so a similar response is appropriate.

This is especially true if the publisher's offer is extremely exploitive of their perceived superior bargaining position. And they may just be in the habit of getting everything that they ask for.

But remember that the initial offer will usually remain there. So, the studio really has nothing to lose by testing the publisher's resistance in the process and making a counteroffer that includes everything that the developer wants and needs.

And in the process don't worry too much about what the publisher will ultimately accept. Let them decide how much they are willing to give. That's their job, not yours.

So if you find yourself holding out on asking for something because you don't think that the publisher will agree to it, don't. Let them negotiate their position. You negotiate yours. And if they are in a position to deal, you can rest assure that they are quite good at knowing what they want.

Developers build games and publishers exploit them. That should mean that publishers exploit the games, not that publishers exploit the developers. What every developer should want in a developer-publisher partnership with someone who is really great at exploiting their game.

After all, the commercial exploitation of the game is where the money comes from. And few, if any, developers are really good at exploiting their own work. But then, few, if any publishers are really good at making games. That's why they keep buying studios.

And it is also may be why so many studios tank after they get purchased by publishers. So long as the negotiation takes this fact into account, it is truly a win-win situation for everyone.

It takes a huge amount of time and effort to make a great game. And it also takes some serious time and effort to make a great deal. And by that I mean a deal where everyone wins, both the publisher and the developer.

So, put the same degree of focus energy and time into the deal they you do into the game and who knows... you may build that great studio in the process.

Til next time, GL & HF!

---

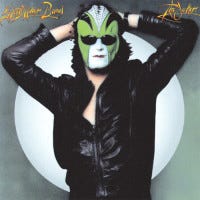

[© 2008 Thomas H. Buscaglia. All rights reserved. Title photo by Scott Maxwell, used under Creative Commons license.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like