Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Notes on getting money, and the strings that come with it.

Before starting game development, I tended to have this notion that, once completed, art sorta existed in a vacuum. High-school-Wick at one point argued that you could seriously judge a piece of art on its own merits, regardless of the context in which it was created or the artist’s intentions.

I now appreciate how the environment that a piece of art is designed for totally dictates the shape of that art. These are design decisions that are so fundamental, that feel so natural, they’re invisible unless you’re looking for them. One of the reason Charles Dickens’ books are engaging is that he ends most chapters on a cliffhanger -- due to the fact that he originally wrote the chapters for magazines and needed to get people to buy the next one.

In games, the most clearest example of this is the concept of "lives". Needing to start a game over from the start if you fail a few times wasn’t something a designer came up with because they thought it would enhance the experience; it’s because it drove people to insert more quarters in the machine to buy more lives to continue their game.

An arcade machine’s entire design -- lives, levels of increasing difficulty, high score lists, colorful graphics -- is molded around its business model. This isn’t inherently a bad thing; you can find games that worked with this structure to tell a story (such as in Missile Command, which was developed during the height of the cold war and whose mechanics demonstrate the inevitability of mutually assured destruction). However, the structure itself is unyielding. The economics demand it.

Again, this isn’t unique to games. Every creative discipline has had some form of this conversation with itself. “Can art for art’s sake exist? Must we be shackled to the cruel realities of this cruel world?”

Yes, we must. We, physical beings, are making something for other physical beings who also exist in a physical world. Although people do find ways to make their art with fewer economic constraints (like working a day job or being supported by a partner), if you want it to become self-sustaining you eventually need to figure out how to get this physical world to support you.

And by definition, this business model will in some way dictate the shape your game takes. The unexpected implication of this, for me, has been that I can’t design the core gameplay loop until I know where the money is going to come from. There’s only so far that “I’ll build the thing and figure out how to be paid later” can take you.

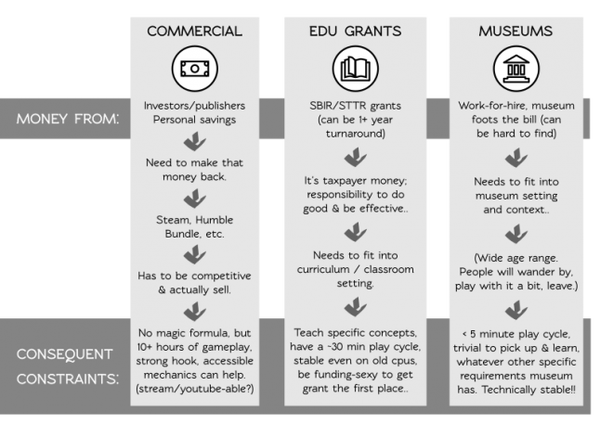

So! I’ve been reading, going to conventions, and talking to people to try and puzzle this out. Here’s the general picture I’ve pieced together of the relevant* sources of money, and the design constraints they come with:

Commercial is the general default for indie developers - they make games for Steam, the App Store, etc. Since many devs come from a background of playing games, it’s the environment they personally have the most exposure to. It’s a big market with lots of room, but is also highly competitive. To make the initial investment money back, there’s not much room to deliver experiences other than multiple hours of stellar gameplay.

For the indie creative simulation genre (Kerbal Space Program, Besiege), I’ve been told you need 20+ hours of content, to be easily streamable, and the first hour’s experience drives people to talk about it online to share tips and watch videos.

Government grants are an underappreciated avenue for games that do a social good or push human knowledge in some way. They apparently take a lot of skill and time to get, but SBIR grants can be up to $250,000 (and you can get one twice, each at a different phase of development!). This is money that you don’t have to pay back! However, since it’s taxpayer money, you have a strong obligation to make sure your game will be actually able to do the thing you said it would. For games that will be used in educational contexts, this means designing to fit into a curriculum and classroon session (~30 minutes).

Museums weren’t something I’d considered until a conversation I had at the Games for Change conference. Apparently, museums sometimes contract developers to make games that fits into their exhibit, and that I might be able to approach them with an offer to make a pick-up-and-play version of Crescent Loom for them. In the digital realm, companies like Brain Pop also commission educational games.

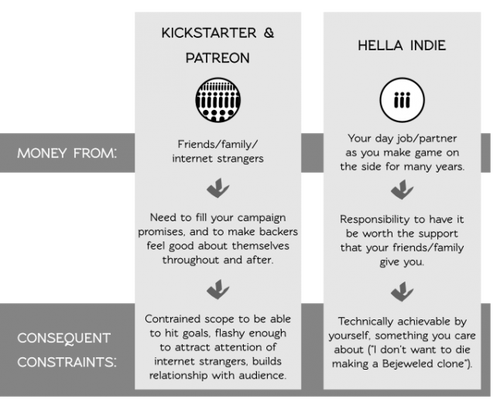

Know what? I had so much fun making that first infographic, I made another:

Lots of Kickstarter games are geared towards eventually entering the commercial market (and have the aforementioned constraints thereof), but it doesn’t have to be like that! One of the best examples of a developer using crowdfunding for games that stand on their own has been Nicky Case. Their games are online, 5-30 minutes, free, and illustrate dynamic systems that have wide social or psychological relevance.

Finally, it’s worth noting that there’s no such thing as a solo developer. Even people like me who are the only ones literally working on the game are only able to do so with the support of our friends / family / loved ones / online & offline communities. Village, child, etc.

These paths aren’t linear; they can branch and cross over into each other’s end environments. Universe Sandbox was developed as a hella indie game for ten years before becoming popular on Steam. Minecraft has been modified to be used in classrooms. Most Kickstarter games end up being sold commercially. The constraints accumulate as you add more environments, but people manage.

So what does this mean for Crescent Loom? My immediate objective is to fulfill the Kickstarter campaign goals, but following that, where is it going to end up? I see a two possible paths, both of which pull from multiple columns.

Find an investor or publisher who’ll invest around $40k for another year of development and so I can hire somebody to write an SBIR/STTR grant.

Using the grant money, I could develop for another few years, pay for better art and music, and work with an educator to tailor the game to fit into some kind of educational space.

When it’s ready, sell it to school districts or as a supplemental educational tool to pay back the initial investors. (could possibly spend a bit more time/money on it at that point to make it a solid entertainment product, too)

Failing to find an investor, I move down to the bay, get a job (or go to grad school?) and go hella indie for a bit.

Not having the expertise to enter the educational market, I work on getting it ready for a run in the commercial market. Eventually go Steam Early Access and see if I can sales to be self-sustaining.

The museums/work-for-hire column is inviting, but I don’t know enough about it to include it in my planning. It’ll be more of an opportunistic thing, or if I end up working with a publisher who’s willing to explore in that direction.

Either way, my sorest need is to find somebody to work with who can help with marketing, educational market expertise, and grant writing. As soon as I get resources to get help, that’s where it’s gonna go. I have more ideas on the backburner, so ideally when Crescent Loom wraps up I’ll be in a position to crowdfund them and keep this career of educational game development running.

Haha, I guess sometimes half the trouble of working on a project is setting yourself up for the next project.

Jeez, I didn’t event get around to the actual progress update. Gonna split that off into its own post, here.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like