Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

So, Nights has finally been rereleased on the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, and we're hearing that it's not all it was cracked up to be 16 years ago. Here's one Gamasutra editor's take.

Last night I downloaded Sonic Team’s Nights from PlayStation Network and began to play it. During the day I’d heard rumblings on Twitter that suggested people don’t think the game stacks up to its reputation -- that it hasn’t aged well, that it was overrated to begin with.

This is a bunch of horseshit.

I’ll admit that I wasn’t able to actually bring myself to read, for example, the Polygon review of Nights, because the subhead -- “Sega shows a loved classic plenty of respect in this remaster, but Nights doesn't stand the test of time” -- told me everything I cared to know about it. I quickly realized didn’t want to hear about why. I wanted to experience it for myself.

So I downloaded the brand-spanking new, HD port of Nights on PlayStation 3, curious to see if this was true. I’d loved the game in 1996, but things have changed a lot since then -- or so I thought, anyway. In some ways they sure have, but playing Nights reminded me that in many important ways, they have not.

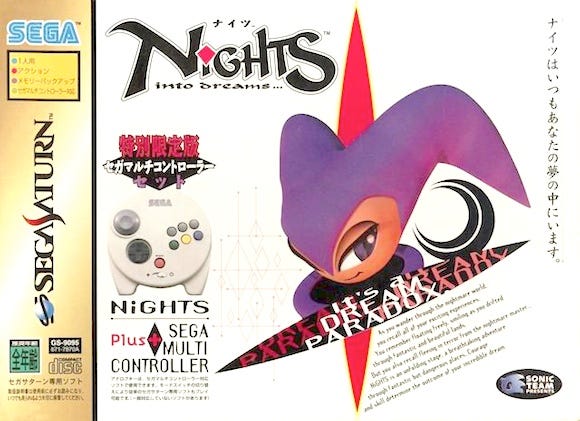

I remember getting this in the mail in 1996.

I can barely describe my feelings when I first booted up the game. It was a tsunami. I was awash in nostalgia while dreading the idea that the critics might be right, and just plain tired and stressed from work and life.

A couple of hours later, I liked Nights better than I did at the time, and for what I would call more salient reasons.

To love Nights, you really have to understand its design. I was about to write that “you can say that about any game” but these days, that’s not actually true. So many of today’s games are designed to be experiences that people progress through once, and that’s the end. Understanding a game is something only its most hardcore fans can be expected to even consider.

Developers talk of signposting things for players, making things easier for them. In Nights, you can’t access the game’s final level until you get at least a C ranking on the rest of them -- something that’s not going to happen until you begin to understand the game.

At the time, people scratched their heads at the game because it wasn’t a linear platformer -- because that’s what they expected from Sonic Team, the creators of the Sonic franchise (which, back then, had only ever been presented in 2D.) If anything, I think things are even worse now, because Nights is in a real no man’s land of game design. While platformers don’t have the currency they once did, today’s mainstream games are either tightly controlled and linear or total sandboxes.

Nights is a game about risk and reward: trying to score as many points as possible by learning the best routes through its stages and using every possible second of its constantly ticking timer to your advantage. It’s a very lean, very clever design, and also an inventive one. It takes key ideas from Sonic -- speed, maneuverability, collection -- and amps them up, stripping away the rest (so much so that it’s, at first blush, confusing.)

It’s a game that grades you based on your performance, as I mentioned. If you’re not into the idea of getting better at a game that you’re playing -- practicing and improving -- well, you’re not going to be into Nights. But that’s your problem, not Nights’.

Not every game is, or should be, an endless parade of new content, and Nights only shares its secrets with you if you can figure out how to find them. Nights is a game about flow -- getting into the groove, learning to play the game, learning to get better at the game, and not wanting to do anything else.

I had to tear myself away from the controller to go to bed.

Nights also stands out simply because of how joyful it is. It's purely a game about wonder, excitement, and feeling good: beautiful dreams of flying. Aesthetically, it's unified around this, from the visuals to the music. The game also constantly tries to surprise the player, with clever and amusing ideas -- rings you can only see in a mirror, for example -- sprinkled through the levels to add pique.

This game came from an era when we weren’t spoiled by the capabilities of our consoles, and developers did the best they could with what they had. So while I’m no longer amazed by the realtime environmental deformation in the Soft Museum level nor dismayed by the faked transparencies in Splash Garden, I’m still astounded at what a cohesive, evocative aesthetic package this game offers. Last night, I felt better after playing Nights than I did before playing Nights.

In fact, Nights is unique, in the true sense of the word. You hear that word a lot these days -- usually paired with an adverb, such as “very unique” or “somewhat unique”. This usually means something is very slightly inventive.

Those constructions water down the word’s primary meaning: the only one of its kind. And there is no other game like Nights. I also don’t like what they imply about creativity. There is no other game that feels like Nights, looks and sounds like Nights, or plays like Nights. For that reason alone, I think it deserves recognition and respect -- in the age of clones and endless riffs on whatever’s working this year.

If you can’t play and enjoy Nights, well, I’m sorry for you. Because it’s a taut and beautiful game -- not a flawless one, of course, but one that goes for a design you can’t find in any other game and does it extraordinarily well. It’s part of video games’ canon, and should be thought of that way, not as a quirky old game that just doesn’t make sense anymore. Its design is as solid as it was in 1996, and it still has things to teach us if we just keep our minds open.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like