Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Nimoyd is not only a game – but an indie story about two friends who were searching for that one awesome game idea. When we almost gave up on Xmas 2018, it clicked. We quit freelancing in 2019. Today, a small team. But it started humble, with 2 friends.

Hey guys,

Now that our first trailer and the Steam page are going online in a few days, I thought about reminiscing the history of Nimoyd with a devlog.

Nimoyd is not only a game – it is also an indie story about two friends, Jeffrey and me, who were searching for that awesome “Whoa” game idea since 2016. It is even kind of a Christmas story because after a long period of prototyping and struggles everything suddenly clicked around Christmas 2018. Until then it had been quite some time of prototype twists and changes, struggles with the budget, even some extensive freelancing, and being close to giving up. And then, whoa, bam, we had it, and last summer 2019 we finally hired more people to finish the game which will now come out in a few months in 2021. Still independent and self-funded, still working from home. But it all started humble – with 2 friends working from their living room, burning through savings.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Rather Humble Beginnings (2016)

Back in 2016, we’ve been prototyping a flat 2D survival game, set on Earth in the future. The idea tracks back to a game jam prototype that never made it when I got sick in the middle of a game jam, which I eventually revived for a new try.

Nimoyd had originally no voxel engine nor was it 3D, and no pixel art. I’ve been into survival games so much, so it was meant as a decent 2D side project about generated cities and nations, or something along those lines. At least back in 2015 and 2016, cities and villages in survival games felt rather dull and unimaginative. I wanted to change that and wondered if we could add RPG abilities to the mix as well.

With that premise, we set out to create a 2D-only survival game with hand-drawn animations. Jeffrey is a 2D artist, so this was a natural choice. For me, who didn’t work in 2D for many years, it was refreshing: No draw calls, culling, lightmaps, or another voxel engine anymore, I thought. It felt easy. What could potentially go wrong, right?

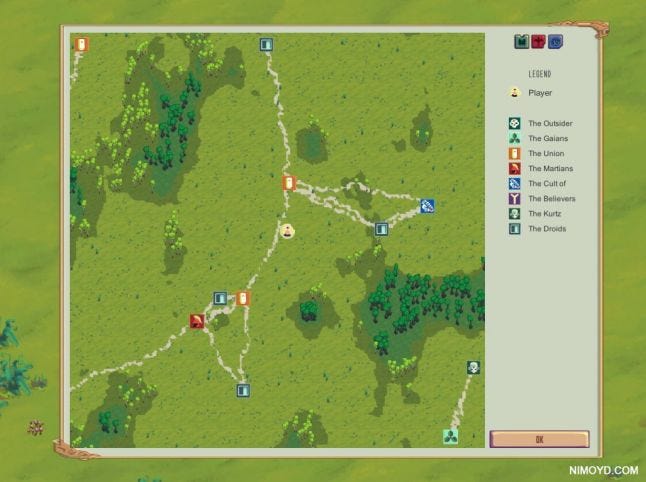

Although some screenshots did look great on Twitter and Tumblr, with factions, buildings, the survival mechanics, the game didn’t feel right.

Combat animations proved to be tricky. I contacted the animators behind The Banner Saga (which is an independent animation studio) and was surprised how expensive their animations are. Side animations that are common for most 2D games, like platformers or metroidvania, do not work well from an isometric perspective, so it needed to be something like The Banner Saga. But this requires better animators who are good at perspective and anatomy, and it becomes a bigger problem when you add fast-paced real-time combat. For an indie studio this is a nightmare.

We could have spent a little more time on the animations, combat, spells, and artwork, of course, but I was just not happy with the result. It was at that moment when I decided to talk to publishers. Their response confirmed our fears. Three publishers reminded us bluntly that the game has no future, it is not fun, it will not work… unless they put some extensive money into it, and so … I was shattered.

Adventure Game (Late 2016 ‘til February 2017)

If you work for a big company like Walmart, Ubisoft, or EA, this is the moment when you scrap the project, right? If so many people advise you to give up, or to release what you have and move on, you move on with the next project. For an indie studio or startup, this can be a matter of survival because if the budget is gone, there is no company.

Jeffrey became a father for the first time. We needed to do something, or else he was forced to leave Nimoyd (until I’ve secured the funding again, he said). We knew that I was making as a programmer freelancer more than him. So it all would depend on my freelancing again. While he would keep working on a new game, an adventure game about an orange-colored president and a fierce jungle bro-warrior as roommates, I would provide the funding through freelancing and code at night and weekends – almost like before.

We changed our mind after 8 weeks. That adventure game, influenced by Seinfeld, was cool but, well, not big enough, not cool enough, not challenging too, compared to Nimoyd and other games. We went back to the project’s roots soon – but this time with a different visual style.

Pixel Art Nimoyd (February 2017 until Winter 2017)

I recall how Jeffrey and I made a call about Hyper Light Drifter at night, and how it dawned on us that we should try pixel art ourselves. Hyper Light Drifter, Enter the Gungeon, and NES Metroid, Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup or the MSDOS Sid Meier’s Pirates being my all-time favorites, it felt so obvious and easy to make that decision.

And as soon as I saw Jeffrey’s first pixel art concepts, it just clicked. It felt like a fresh take. It didn’t just look better; it saved our small studio.

For a few months it all looked great. While Jeffrey recreated all the artwork as pixel art, which is faster than high resolution non-pixel art assets, the early animations too were great; not perfect, surely we needed an animator eventually, but still: it was nice and sound.

With the new funding from freelancing, we were financially safe, but since I cannot clone myself (yet), I was unable to work on Nimoyd as hard I used to. I had to make the time, nights and weekends, putting my relationship at risk (again).

Jeffrey asked if we could just create a completely new game, which was a good point, right? If we want to recreate and redo everything, why not just do a normal pixel art RPG or something else, pixel art-ish? Well, I guess I am too much into survival and procedural games myself, and I liked Nimoyd, that little alien teenager, too much. So we decided to create a “Nimoyd 2”, a fresh take on the original idea, in pixel art.

And it felt great. Although my working hours intensified again, and Jeffrey complained a bit about sleepless hours thanks to a newborn human being, we were full of ideas and on fire again.

Pixel Art Buildings (2018)

By the end of 2017 we had an interesting game that was 2D, kind of top-down or isometric, and pixel art. We were still independent because I was freelancing, but this also led to less pressure budget-wise, which allowed us to try out different mechanics and ideas, actually. This rather slow and long time period allowed us to take a step back and rethink the whole game, and what we want to do, regardless of what someone says.

There was still an open issue though. What about buildings and multiplayer? Most pixel art games are flat for good reasons.

The 2D terrain is perhaps emulating depth and heights, but we all know that it is not really 3D. Knowing games like old UFO and X-Com Terror from the Deep from the 90s, I thought that it should be easy to create a multiplayer version of an isometric pixel art game – but it is not. Unless you hack the y-positioning of your networking code, the server will need to find a way to “hack” the bullet targeting and hitting in a way that emulates terrain and building heights… which sounds as awkward as it is. We are in the 21st century. I felt that there must be a better solution.

By Christmas 2018, we had a tileset building system on top of a 3D engine that was using 2D assets, and to me… it was okay and pragmatic but I really was missing that visual surprise, that feeling that you have when you look at something, and it does not need to be an AAA game, where you say: Whoa, this is super hot, or at least: Whoa this is interesting. It means, we could have released such a game with some extra art and effort but to me it was not enough. I didn’t want to create another tileset based pixel art game with bullet hell game mechanics. And so, out of boredom or silliness perhaps, a new visual style was born – during Christmas which may have been the best Xmas of my life.

Nimoyd with a “Whoa!” (December 2018 until July 2019)

When Jeffrey returned from Christmas in January 2019, I had a surprise for him.

What if we use a voxel engine for the terrain and the buildings? It would allow us to create awesome landscapes and large buildings. It sound stupid, and maybe it was. But placing voxels would be easy. Entering buildings too. Shooting missile launchers from the top of the building would be a no-brainer. And here’s the thing: I had for years experience with voxel engines, so it was super easy for me, and so I showed Jeffrey an early hacky holiday prototype before he could even think about an answer.

I believe that if you want to land a hit, you need some kind of Whoa-effect. That “Whoa!” or awesomeness may come from extraordinary visuals, storytelling, a theme, or even the mechanics. Most tiny teams try to create that Whoa based on either some retro, vintage or niche-looking visuals (I’m sure that there is a better way to phrase it, but you probably know what I mean) or with some witty new game mechanic. How else to land a hit without a huge AAA 3D, storytelling, programming, and marketing budget? It is your only chance to reach millions of people – like some super cool, never-heard-before jingle or song, right?

If your game or product does not have that Whoa-effect, there is a good chance that you will not make it. If it looks like Stardew Valley, Don’t Starve, Minecraft or Hyper Light Drifter, and if it plays almost the same, you will not make it (except for a few hardcore fans and gamers, and perhaps some niche fans). It’s not “whoa” enough to most of us, I guess.

For us, changing to voxels was such a “Whoa” moment.

A survival game using a voxel engine, with water physics, 2D animations and trees, and some end bosses in deep dungeons?

What started as a Christmas experiment turned into a prototype, but I instantly felt as if I created something I did not see before. It was rough, it was ugly – but it was different, fresh, and the gameplay was so cool.

Soon it led to numerous improvements, such as tall Lego-like voxels that are not just 1x1x1, so that we had more flexibility. They came in all sizes and shapes, which became a cornerstone of our game today. And so a new game was born!

Nimoyd, Today (Since July 2019)

Thinking about these last lines on a Monday morning, it is rather strange when I think about all that happened previously. I believe it was around July and August 2019 when I started to hire more people.

From 2016 until then it was largely just us, Jeffrey and me, with support on occasions. Finally, I told Jeffrey that I’d like to hire a full team, to get the game done. The screenshots I made during that time, where I added more life sim and building features, all impossible before, felt great; it was rough but we already saw what was possible.

That last part probably requires another article because we went from a 2-man team that worked at night and on the weekends, to a team of today 13 people. Still independent, still self-funded, still working too hard. But of course with being closer and closer to the release, with publishers knocking at our doors, it is a completely different story now.

With our first trailer and the Steam page going online in a few days, it feels like a huge step to us.

We are nowadays at a point where several publishers contact me for months, trying to land a deal with us, even without funding. This feels way better than back in 2016, 2017 or 2018, for sure.

We do not know if Nimoyd will become a hit, or even a small success, because who knows. So much can and will go wrong. But judging by the feedback from our fans (hey there), Youtubers, and the publishers, we have this time at least a good shot here, hopefully.

A Few Takeaways

I wonder if it is now worth mentioning a few takeaways in this story, in case you made it to the end of this article, for which I am eternally grateful. Of course, everything I’m saying is highly subjective. Of course, this is not a post-mortem, and everything I'm saying can be easily questioned when Nimoyd fails commercially next year, but if it helps one or two game devs to some degree, it's fine to me, and feel free to make fun of me, lol, so here are a few points I find worth mentioning (today).

People talk a lot about marketing and PR. The reality is that if you have an interesting game with an “Whoa effect”, you’ll do fine, no worries. Yes, perhaps a big shot AAA company would sell your game better but so what? Your ultimate goal as creator should be to create a game or product that is awesome. Do you think that a great game like Among Us would be missed by the press or the players, ever? Nah. Of course not.

How do you know that you have a “Whoa”-game? When the money comes to you. If enough people on the interwebz tell you that you are great, you may be thinking that you made it. In reality, we all have seen games that did great on Twitter which then failed at release. When bigger publishers are willing to give you money in addition to marketing etc., this is the moment when you know you may have something of value. If they contact you, and you do not need to beg for money, you know your game could become big. I do not mean Whoa Whoa Whoa by a fundamental, groundbreaking super innovation that changes gaming forever; rather, something that brings enough public attention to your little game that the public catches fire, for a short while at least.

Do not work on a game that is not your favorite game genre. I literally mean the genre you play the most, or a lot. If you are not into strategy games, you will likely fail at creating an awesome strategy game. Why? Because you are not deep enough into the genre’s history and conventions to understand what players of that genre would consider new and fresh. I was so many times glad that I understood survival games better than most people I talked to, especially in the early phase. We tend to play all kinds of games but it really helps if you are into your game's genre.

Aim high. For some strange reason most lower and middle-class people, like us, believe that if you build your studio small game by small game, eventually it leads to a big success. Reality shows this is not how it works, most the time. Nobody cares about a studio that shipped 10 tiny ugly mobile games that barely made it, right? Because it’s like being the last at the Olympics, for 12 or 20 years. If you feel that "any" release would be a big accomplishment already, sure, then your bar is extremely low for good reasons, but aim perhaps with your next game or project higher? Not unreasonably high, like the next League of Legends or World of Warcraft with a team of 2, but within your budgetary, time and (both artistic and technical) skill limits, of course.

Do not get scared by the number of released games. I've heard this before many times, and I'm not sure exactly why some people are obsessed with the size of the "market". First, I strongly suggest checking the concurrent player stats on SteamDB or SteamSpy. You'll notice that the whole Steam universe plays barely 1,000 different games right now (concurrent players > 200), of which many are dinosaurs or live in a different dimension (i.e. Rust, PUBG, or DOTA 2). Second, it means that the public has an insatiable thirst for new game titles, fresh game ideas, awesome mechanics, and cool game stories. It will never change. Do not worry about the doomsayers. Just create a game that stands out in some way, with perhaps one or two somewhat unique ideas.

Be cautious about procedural game prototypes. Procedural games tend to have a long time before its actual procedurality looks cool. Publishers do not like, and often do not understand procedural prototypes at an early stage. I suppose this is the biggest reason why almost all AAA game companies fail at procedurally generated games. It is what went wrong for us in 2016 when I thought that we could show awesome procedural mechanics with nations at war, with NPC governors talking, but cheap animations? Nah. No way. Therefore, if your game is procedural, do some gameplay prototyping but do not compare yourself to a level-based or static games. I know by now a lot of game devs who got lost with their bigger procedural indie game releases in game engine madness, which prolonged the development, caused headaches with the publisher (if any), to sparse or no success. Solve the visuals first because your procedural prototype will eat up a lot of development time before it will be able to impress any casual gamer or non-techie who is just into games. If you can show early how combat and animations feel, your game is easier to pitch, in case you run out of money, by the way. I know someone who pitched his game to a bank when he needed a loan, but I'm unsure if this is the best solution; however, you probably see my point: that bank employee there had for sure no idea about the worth of a game in progress, so all he or she sees are the visuals, the anims, the combat, and the gameplay feel.

Never contact publishers. Let them contact you, if you want a publisher. Find a smart way to help them stumble upon you and your game instead. PAX, GDC, etc. are great at it, but guess what, we did not attend those yet, so we somehow made it without it.

If a publisher contacts you, show your game as late as possible, literally when you are about to run out of money. Why? Because at that point your game looks the best. Publishing “business developers” and “publishing directors” are no good game developers or game designers, but they are great at judging your game from a player and press perspective. It means, in the same way, you’d pitch your game at PAX to a player base, show off the best game possible as late as possible. Keep in mind though that any publisher negotiation may take another 1-2 months, so plan ahead.

Knowing what you want to do, at its core, is probably a key to success. It is easy to get distracted by visuals, animations, time and budget pressure, and tester feedback. But feeling that your game idea could work, that it could have a few unique features, makes you not only sleep better but helps you to ignore the doomsayers, and motivates you to keep going and reach that “Whoa” moment that, hopefully, leads to greatness.

If you made it that far, you deserve a medal, and I am humbled by your patience. I'm thinking about changing and expanding one or two paragraphs, or removing some of the takeaways, but perhaps it is at this point, after our long journey, by the end of 2020, the best to document my thoughts this way.

All the best, Rafael (@imlikeeh)

About Nimoyd: Give http://nimoyd.com a try, or go straight for http://twitter.com/nimoydgame, or check out our new Discord http://discord.gg/nimoyd or google for our Steam page in a few days.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like