Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Blockchain, the technology behind Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, will change not only how we pay for but also how we play games. To better understand why, we need to go 27 years back in time.

Blockchain, the technology behind Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, will change not only how we pay for but also how we play games.

To better understand why, we need to go 27 years back in time.

It’s a quiet Sunday afternoon in the year 1991 here in Manila. Sunday for me and my brother is “Arcade Day”, when our Dad would drive us to Robinson’s Galleria to play the latest arcade games. He would give us 50 pesos each (about 2 USD in 1991), and we’d go running off — first to the counter to have our pesos exchanged for arcade tokens, and then more quickly towards the Street Fighter 2 arcade machine, its CRT screen steadily blinking: insert coin.

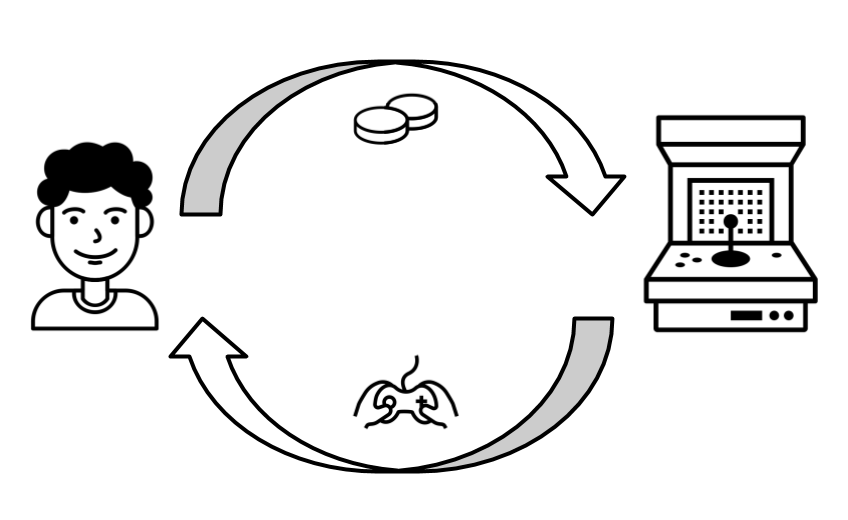

Back in the 90’s, paying for games was a very direct and easy to understand monetization model.

As time moves forward, models change.

The year after, in 1992, Street Fighter 2 is released on the Super Famicom. Me, my brother and our friends would gather at our house after class, happy to be playing the game without having to spend on tokens anymore.

The coming years would have us discover the joys of network gaming. Blizzard’s Starcraft comes out in 1998. 2 years later Gooseman and Cliffe’s Counter-Strike mod for Half-Life would be released. Instead of playing at home like before, we would instead hoof it to the neighborhood network cafe and, at a cost of 50 pesos/hour, play LAN games with our friends until early morning.

de_dust! It’s usually at this point where I heroically bounce a flashbang off the crates and blind my team

We stopped going to the arcades, and the tokens seem to have disappeared.

Playing a game in a network cafe is still the same as buying tokens though, but instead of limited by number of plays the tokens are consumed by the hour. Playtime on consoles may seem like they’re free, but our parents had to pay at least a thousand tokens worth to buy the consoles and then pay hundreds more to buy a cartridge.

Pay to Play was successful for the game industry, enabling it to grow in the late 90’s up to the early 2000’s despite the dot-com crash. This was largely due to new platforms such as the Xbox and Gameboy Advance, as well as a growing, more mature audience.

By the mid 2000’s the industry hit a wall. As typical of maturing markets, competition was fierce, making it harder and harder for developers to make a profit. The console market was saturated, and it was costing more and more to make games.

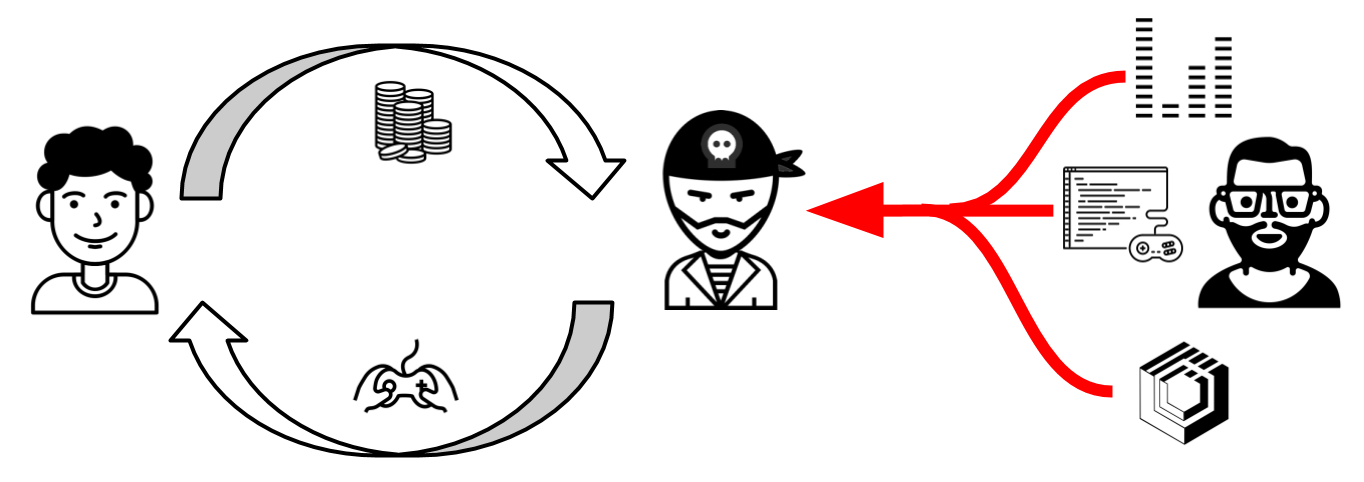

Most of all there was a looming threat from one of the game industry’s main villains — Piracy.

In those days, people here in Manila would buy their games from one specific place— Virra Mall in Greenhills. Virra Mall was like a typical electronics mall you’d find here in South East Asia, but it was famous for one reason: the pirated video games. With the games there being so cheap and readily available, hardly anyone bought the original versions.

The piracy problem also spread to the network cafes. Copy-protection was easily bypassed by tools which were easily distributed through the Internet, so most of the network cafes would just run pirated versions of Half-Life, Starcraft and the latest hit game, Warcraft 3.

The game industry didn’t really have a strong answer to this. There were some attempts at alleviating the problem though: one of the most successful strategies was requiring players to be online and then charging for access. MMORPGs such as Ragnarok Online and World of Warcraft were able to do this successfully. This only worked for Internet gameplay though, not LAN or single-player which were more popular then.

Other strategies were mostly ineffective but, behind the scenes, a radical thought was spreading throughout the industry —

“What if, instead of paying, the players were able to play for free?”

The late 2000’s saw the continuing slowdown of the game industry. I had recently founded a game startup, determined to go from playing games to making them. This was also the time that Defense of the Ancients (DOTA) took the Philippines by storm.

DOTA, a mod of Warcraft 3, was so successful that the network cafes stopped playing Counter-strike and Ragnarok Online. Every screen you saw in a network cafe would be playing DOTA. People were installing them on office computers and playing on lunch breaks and after office hours.

As young game developers we were creating mobile games for Java phones. DOTA influenced us a lot and we wanted to make a mobile version called Anima Wars. The game earned some recognition, but the infrastructure for mobile games and our capabilities back then weren’t mature enough for the game that we wanted to make.

Meanwhile, the game industry was finally able to find cracks in piracy’s armor.

The first one to arrive was Social. Facebook had just overtaken Friendster in the Philippines, and people were playing this new game called Pet Society. It was a game you played on Facebook, allowing you to customize your pet, invite your friends’ pets over and take pictures with them. It was free, but you could opt to spend virtual credits to purchase premium items that other players won’t have. Even if most people weren’t paying, there were enough players that some eventually paid the premium and sustained the game.

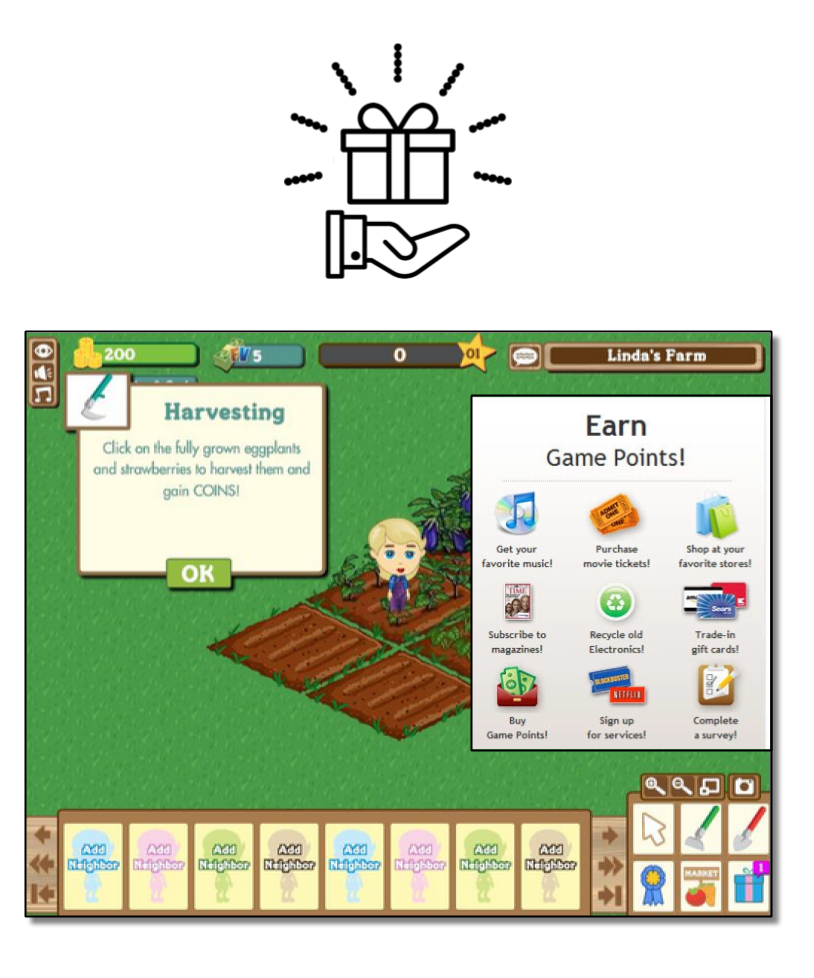

Next was In-game Ads. A players played social games for free, developers found other ways to still get value from them. One of the games that lead the charge was Farmville. Back then ads didn’t come in the same manner as they do in the games we play now — they were called Incentivized Offers: instead of buying virtual credits, you could earn them by completing surveys or signing up for trials. If people weren’t paying, there would at least still be sponsor companies willing to pay for their costs.

The last one was Mobile. The iPhone, the App Store and the new wave of touch-enabled smartphones opened up a whole new audience for games.These phones weren’t like the phones we were making games on in 2006 — they were simple to use and it was easy to download games for them. It was a perfect fit for short casual games such as Popcap’s Bejeweled. By 2009 more than one billion apps will have been downloaded in the App Store. By October of that year, people would be able to start downloading apps for free.

The story of the 2010s up to now has been largely a story of Free to Play’s growth and eventual dominance.

In network cafes here in the Philippines, people moved from playing DOTA to DOTA 2: Valve’s vastly improved version with a Free to Play monetization model. League of Legends, another game in the same genre (now called Multiplayer Online Batte Arena or MOBA), also emerges as a heavy competitor.

Piracy wasn’t a concern anymore. People can download these games and play them for free. They monetize not when people play them, but when players purchase skins that they use when they play the game. They also makes use of other modern Free to Play strategies to monetize further, such as leaderboards, time-limited events and randomized prizes.

In the genres and platforms that Free to Play pioneered in, success had reached massive numbers. It stared with games earning thousands of dollars, growing to hundreds of thousands, to eventually millions of dollars per day. The games that were the most successful were the ones that understood Free to Play strategies and used them to their full capacity.

In the Mobile space, few are better than King, developers of Candy Crush. Originally a social game on Facebook, Candy Crush successfully transitioned to mobile and since then has dominated the app store charts. King knows what works in the platform — they’ve polished the user experience for touch screens down to a science, creating the juiciest animations and most effective user prompts that entice players to keep playing, keep coming back and keep buying those extra lives.

In In-Game Ads, casual mobile publishers like Cheetah Mobile and Voodoo lead the pack, with games such as the current Top Free game in the app stores, Baseball Boy. The top publishers know how the in-game ad economy works, able to not only make games that monetize from these ads very effectively but also create the ads themselves to get millions of players. Voodoo’s games are designed such that watching ads are part of the normal user flow — Even if no one pays, having millions of players watching the ads often enough can make it earn much more than other games do via in-app purchases.

Finally, Social has now been so ingrained in Free to Play design, that game designers also measure success with a social metric: its K-factor. For each player that plays your game, how many more install it after them? The multiplayer, team driven nature of MOBAs has made them the perfect vehicle for this kind of virality. Games like Mobile Legends and Honor of Kings have been able to shrink MOBAs to the mobile form factor — They’ve become so successful in China that the developers were forced to to impose a fatigue system to stop people from playing too much.

As time moves forward, models change.

Last November, Capcom released Puzzle Fighter Mobile: the social, mobile, free-to-play version of Street Fighter. People were vocal about its pay-to-win structure, and how it was too different from its skill-based predecessor. For such a strong and storied license, the game has been unable to break the Top 100 in the app store charts.

Free to Play monetization strategies have also started appearing in paid games. Around the same time last year, gamers were up in arms over Star Wars Battlefront 2’s loot box system. A player computed that it took 40 hours to be able to unlock Darth Vader and play as him, even in a game where people already paid more than $60 just to play the game. The resulting backlash was strong — EA’s response to the controversy became the most downvoted reddit comment in history and spawned multiple memes.

Players have now become disillusioned with the Free to Play model. While it was responsible for reducing piracy and growing the audience of players, it also has a dark side — manifesting in greedy and opaque monetization systems.

Free to play has succeeded, but its scorched-earth approach didn’t just affect piracy.

The token is now obscured in smoke and ashes.

It has been hidden from the equation, replaced with value extracted from the player that is quite nebulous.

We play games for free, but some of them lull us into a false sense of ‘free’. They quietly chip away at our compulsion, making it suddenly rear its head through mind hacks such as time sensitive events and perceived sale values.

Some games turn us into walking advertisements — monetizing our data and our social connections, forcing us to send out invites to friends in return for a few virtual tokens.

Still some others force us to pay with the most fundamental currency of all — our time. They build on our human desire to complete tasks and collections, and those who are unable to pay with tokens are forced to grind away their hours playing and watching ads until the game is more work than enjoyment.

This is the state of the industry now, and as a game developer I understand given how competitive the market is. With so many games vying for attention, we have to compete using the tools we know are effective.

We may be approaching another wall though. Just this year Supercell’s revenues dipped 20%, and the number of Candy Crush users have started declining. We are now once again at a point of the industry where there’s too much competition, not enough innovation and a looming saturation point for players.

We may have to look past our current models and technologies, and find a way to break our reliance on Free to Play. Ironically, one of the means of doing so may be through the use of blockchains.

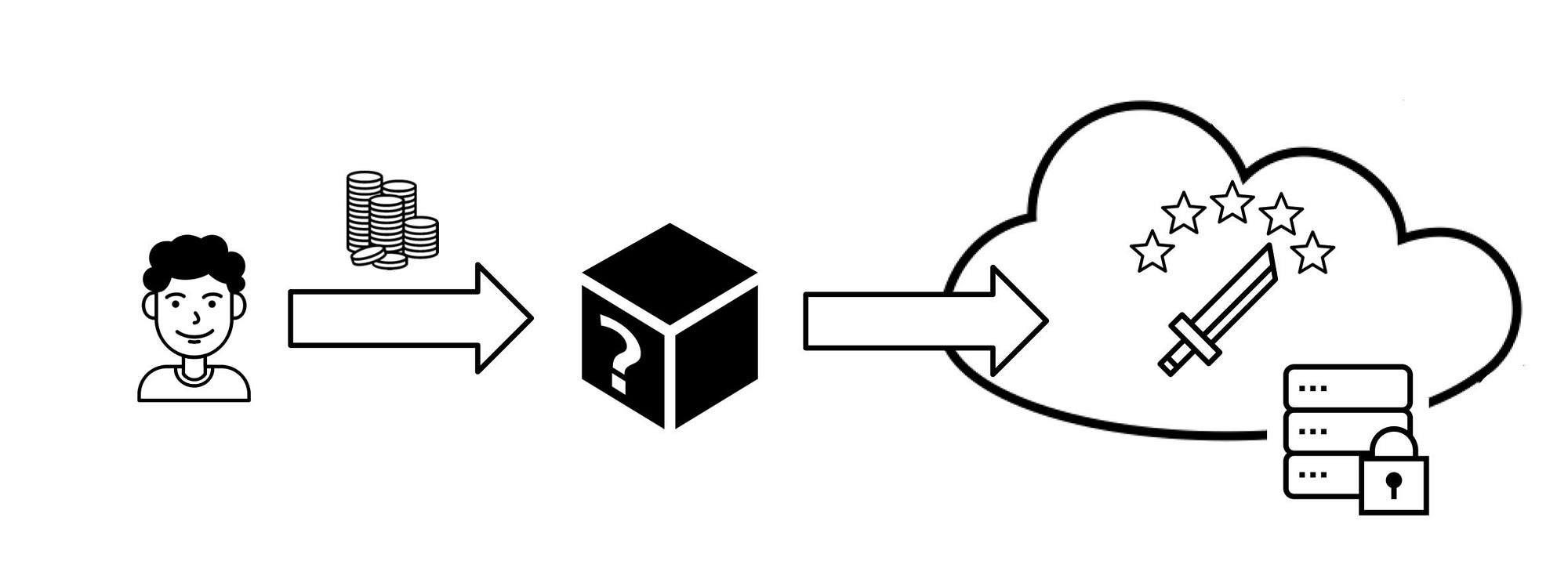

For example, one of the most successful monetization strategies right now is the loot box or gacha model:

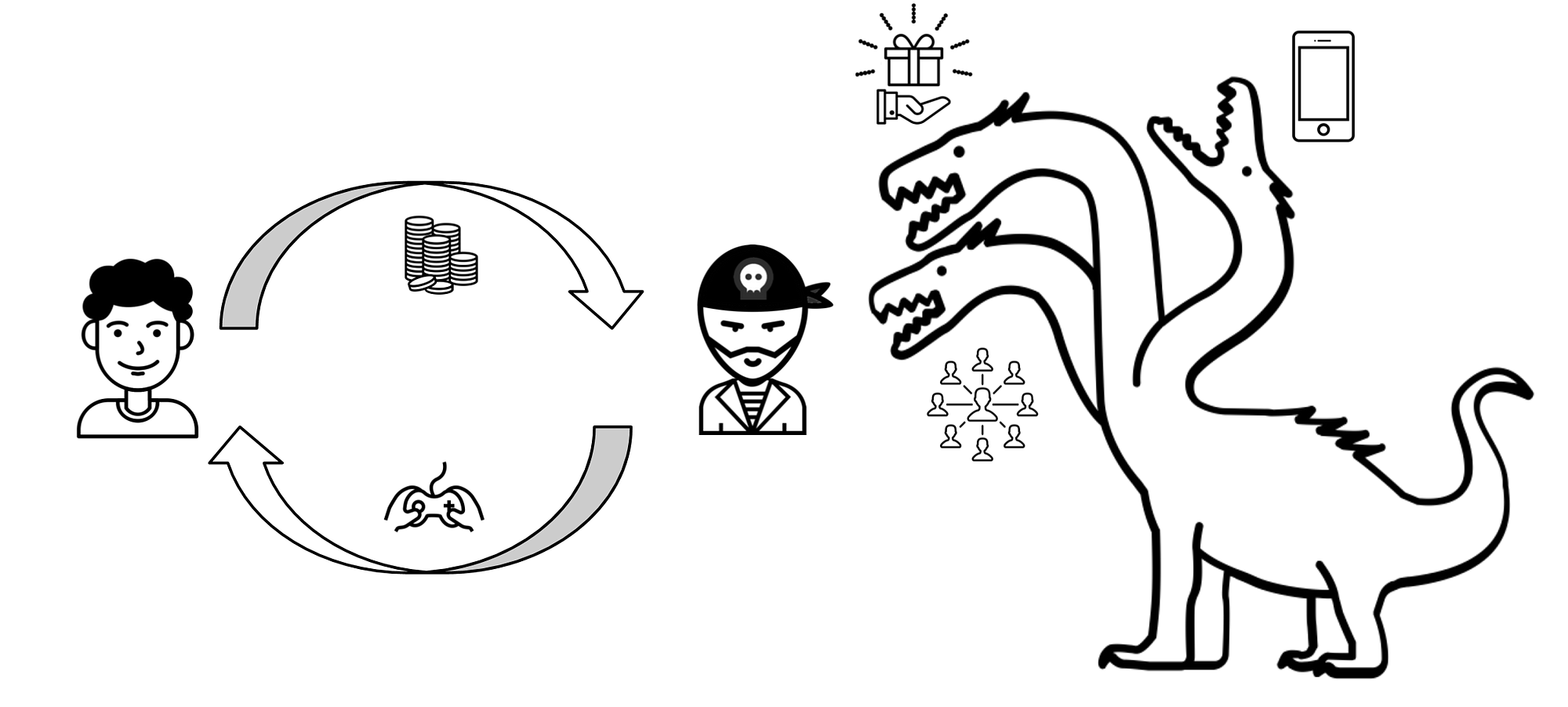

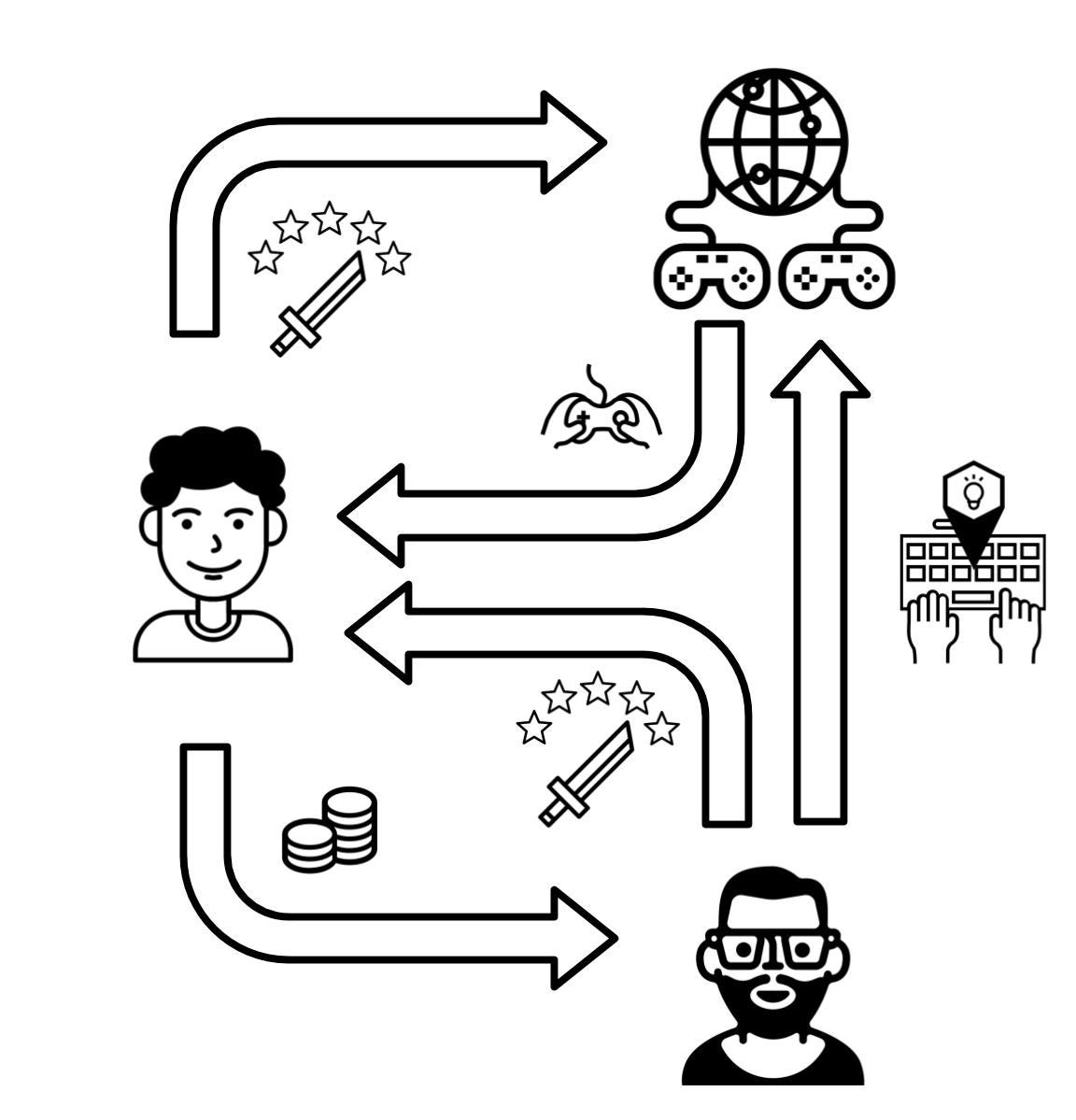

Gacha Model: Player inserts tokens in an opaque blackbox system to get an item. The item is usable only in one game’s internal economy

Used by top games such as Clash Royale, Fire Emblem Heroes and Overwatch, it monetizes players by first showing them items they can buy either through banner ads prominently displayed in game menus or in normal gameplay used by other players. The games are designed to build up a player’s desire to buy the items until he gives in and pays for them.

There are two issues with this: Firstly, a player is usually unable to buy something directly, and usually needs to spend more than what they want to pay to do so. Some games make the chance of getting the items so low and don’t publicize their loot box odds, so the player is stuck spending hundreds of dollars until he gets the item he wants.

Secondly, after the player has spent a significant amount the item that he gets from the game is essentially worthless outside of the game. It’s locked in the game ecosystem, with no option for the player to take it out. This has been always the case with games, but players have always found ways to do so — usually by trading them through a third party exchange or even trading accounts in gray markets. There is clearly player demand for this though, but the prevailing idea is that it always has been beneficial to games and app store platforms to close down their ecosystems.

And so just like in the beginning days of Free to Play, developers started asking controversial questions. The new radical thought, enabled by the blockchain and its core idea of decentralization:

“Why don’t we allow players to trade game items, just like it’s a real item that they own?”

Cryptoitem Gacha model: Player inserts tokens in an open, peer-reviewed smart contract for a provable chance to get an item. The item is stored on the blockchain, making it tradable like Bitcoin or Ethereum. If the user wants to get back tokens for the item, he can sell it to another player and get tokens back in return.

The invention of blockchain allowed exactly that. By storing game items on blockchains instead of centralized servers, these new cryptoitems become liquid, able to easily flow across users. They act similarly to cryptocurrencies: given the right credentials, any player can just send a cryptoitem to another player, without having the need to go through a central authority like a bank or an app store.

Since the blockchain was designed to be transparent, it also eliminates the opaqueness of loot box percentages. Transactions and source code written on the blockchain are open and verifiable, making it easy for players to verify if the developer is providing fair odds.

Free to Play has obscured the token, but cryptoitems and the blockchain may be the way for us to drive off the haze.

There were pioneers such as EverdreamSoft’s Spells of Genesis that saw the potential of cryptoitems early on. Now, with the rising awareness of cryptocurrencies along with the innovations brought about by new blockchains, a new genre of cryptogames like Cryptokitties are starting to break into the mainstream.

This is just the early days of cryptoitems though. The technology and standards around crypoitems are still improving, and once it reaches a tipping point they will revolutionize both how we we pay and play for games.

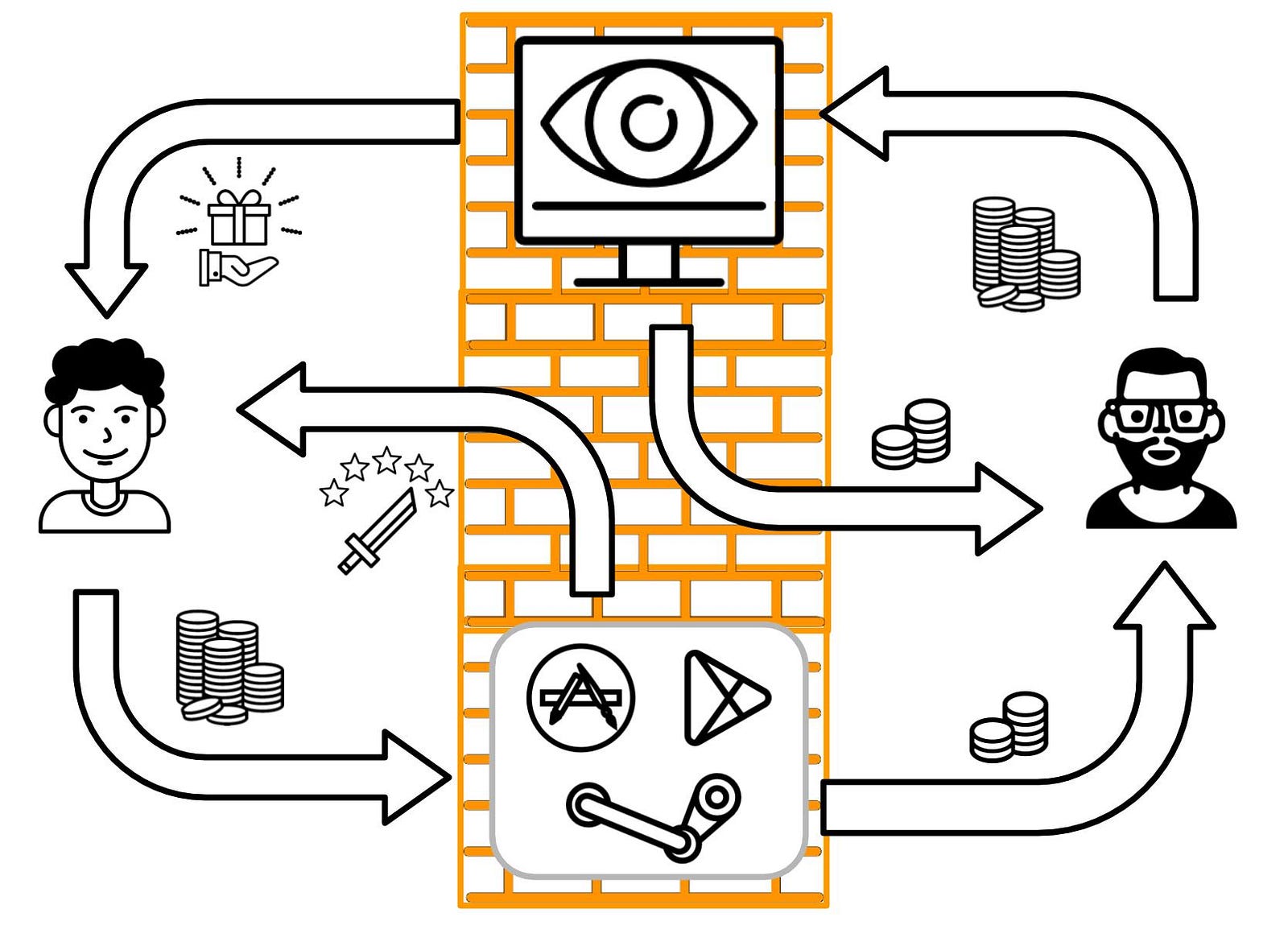

The current free-to-play model. Value usually goes through the gatekeepers first such as ad providers, social networks and app stores before reaching the player or developer.

The current free-to-play model. Value usually goes through the gatekeepers first such as ad providers, social networks and app stores before reaching the player or developer.

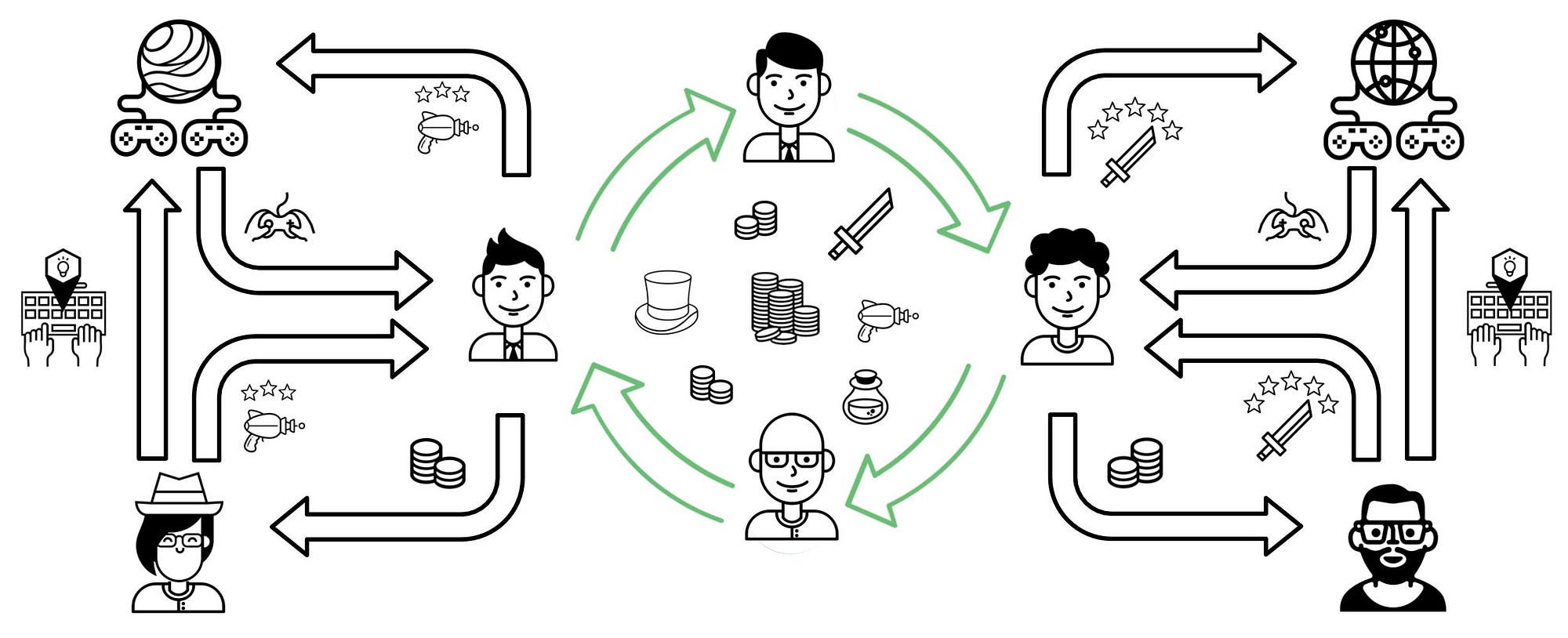

We see it happening now. With Free to Play at its maturity, the economy has started to centralize around main entities: the app stores and the ad/social networks. They serve as gatekeepers, making it necessary for a player to go through them before having a direct economic connection with the player.

By using the blockchain, Cryptogame developers have been able to upend this model.

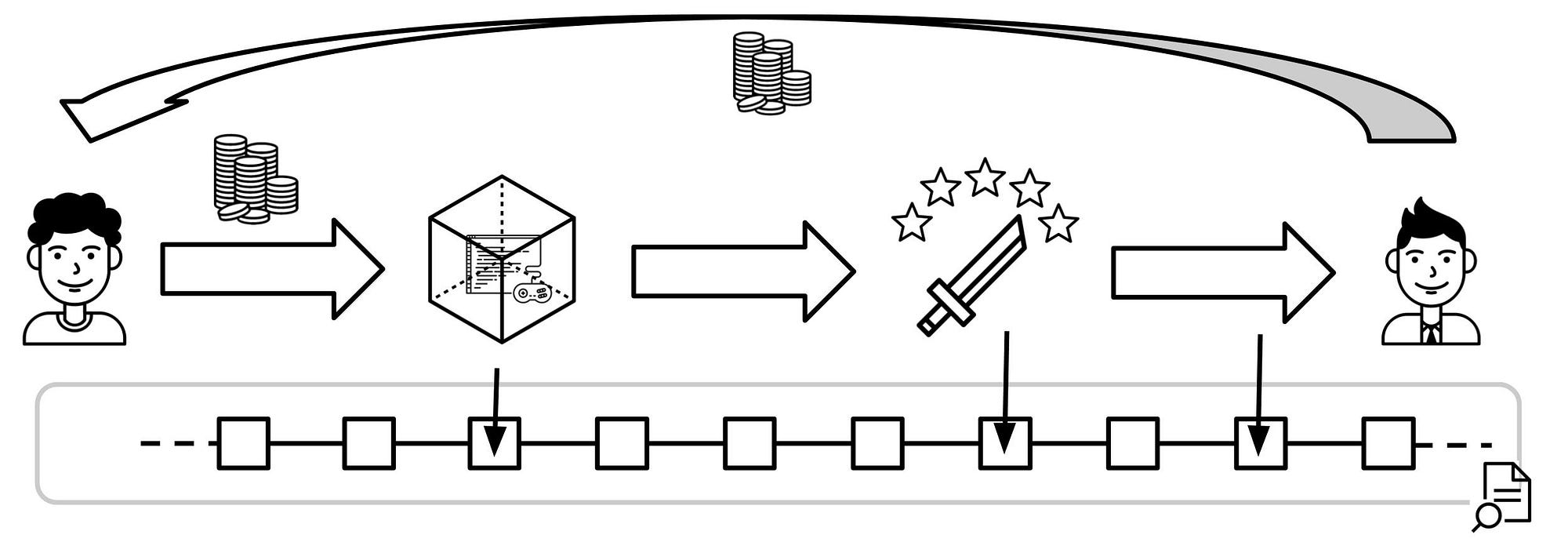

One model we see emerging is the Item First Economy. This is similar to a crowdfunding and early access campaign: the developer creates cryptoitems first, which players can purchase directly from the developer using tokens. The developer then uses the tokens generated by the item sale to fund the creation of the game world. As game development progresses, the player can use the items he bought as the entry point to play the game.

The Item-First Economy Model

Most cryptogames like Etherbots and Ethercraft follow this model. This new model has introduced some interesting dynamics. Aside from making the game fun to play, the developer also needs to be able to prove the value of his cryptoitems — either by increasing their collectability or increasing their utility in the game. Since cryptoitems are easily tradable, the player needs to see their value or else they will just sell them and play a different game. The focus has changed from extracting payment for playing to building sustainable game economies.

This focus on economy building also has surfaced more questions on game design, even questioning traditionally held beliefs. Given the nature of cryptoitems and decentralization:

“What if closed game ecosystems aren’t the best way to make games?”

Imagine years in the future — cryptoitems are already a standard in games, the same way that a 3D file is a standard. There are also cryptoitem specs for item types, like swords and hats.

Airship Syndicate announces their latest game, Battlechasers 2. To support the game, they also start an auction of the limited edition ‘Artifact Blade’ cryptoitem. It is beautifully modeled in 3D by the game’s 3d artists, hosted on decentralized servers and viewable through any cryptoitem web viewer. Most of all, it follows the cryptoitem sword spec.

Warframe started supporting the cryptoitem sword spec months before, making all the swords in their game cryptoitems. This opened up their economy, creating a vibrant marketplace of weapons trading hands among players and collectors.

This also enabled new ways to get weapons into the game. By following the cryptoitem sword spec, any player who bought a cryptoitem sword like the Artifact Blade can also immediately use them in Warframe.

Warframe is not the only game that supports the spec: Blade Symphony and Raw Data do as well. Suddenly the cryptoitem we bought for an in-development game is usable across three different games.

Different games and universes, yet all having a shared cryptoitem economy. It’s a scene straight out of Ready Player One.

The vision for a blockchain connected game industry. Players have a direct economic connection to developers via the cryptoitems that they buy directly from them. Cryptoitems are stored on the blockchain, allowing players to freely trade them with each other and liquidate them. In the future, the standards around cryptoitems will make games have a decentralized yet connected economy, and possibly make them usable across game worlds.

This future isn’t so far off though. We can already see glimpses of it in cryptoitem exchanges such as Rarebits and Opensea. As more and more games and items are built on blockchain the network effects will kick in, until the rolling cascade forces us to recreate our monetization models once again.

And here we are now, back in March 2018, 27 years later from when we inserted that token.

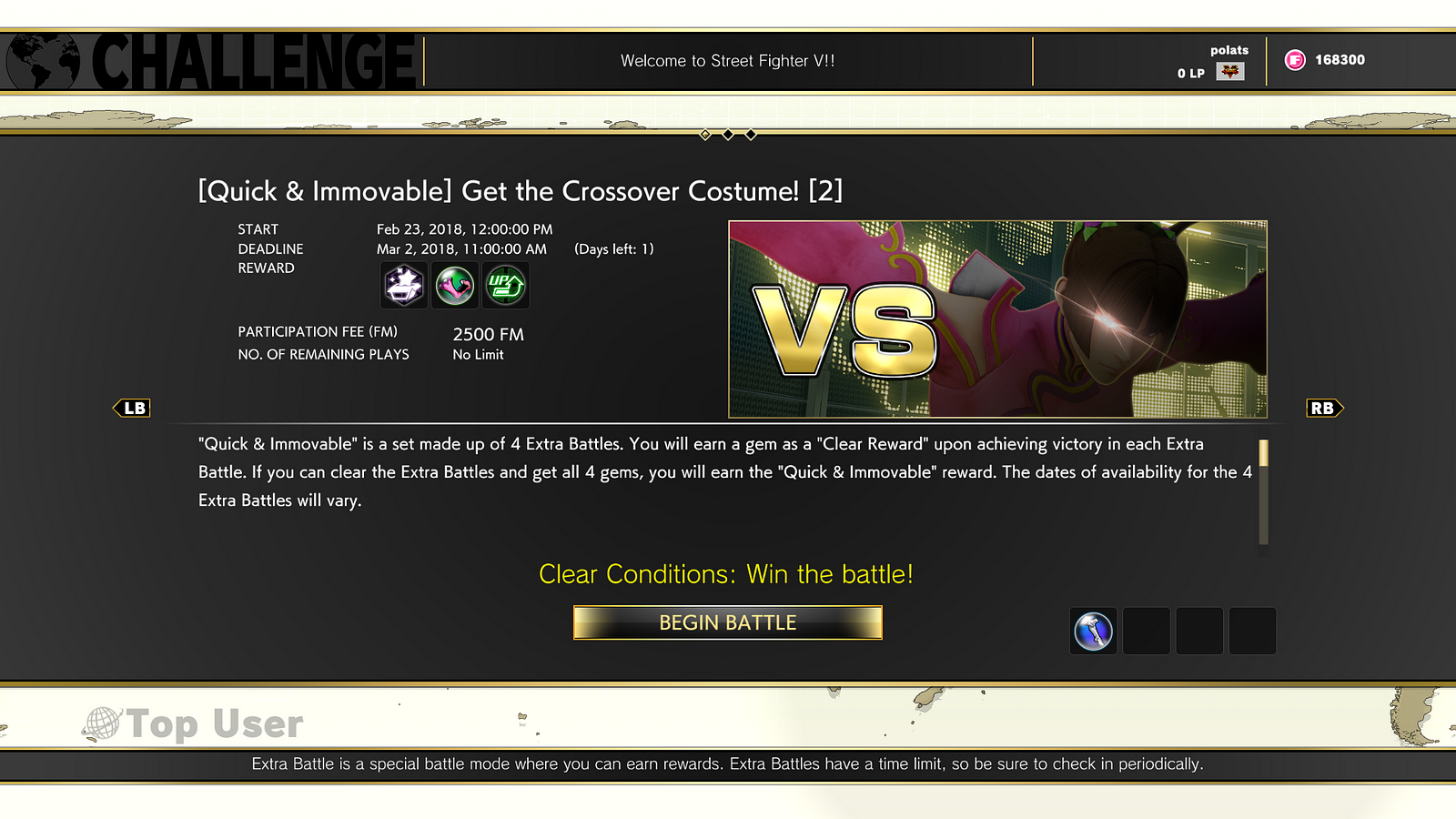

I just finished playing Street Fighter V, doing a quest in order to get a skin that I can only get by playing once a week for a month. It’s a chore, but i’ll do it since it’s painful to know that I missed the opportunity to get it.

This is just how games are designed now. Game developers have had to cope with the realities of a changing market. We’ve had to learn new terms like DAU, LTV and retention. It was a painful transition but I believe it made the industry better, as we now have more tools to create better games.

And that is what the blockchain has the potential to do. It’s a transformational technology that has already affected other industries. It will affect games as well — Token economy design will be the new normal, and new terms such as token velocity, proof of stake and gas consumption will need to be part of a game designer’s vocabulary.

The token in 2018 is vastly different from what it was in 1991. But this time, we have the capability to define its value and its utility.

It’s our own currency — made by our own design and subject to the whims of an irrational market. That’s both an exciting and scary proposition.

How blockchain will exactly affect games will still be determined, but as game developers and technologists we need to be prepared for it to stay competitive.

It is also on us as players to look back and learn from history. We’ve been here before, facing a market that needs to be disrupted. It will be a painful transition, and there will be challenges along the way. It helps to look back — to remember times when motivations were more simple, when inserting a token was a clear and honest transaction between a player and a developer.

Thank you for reading! For more on blockchain game development please join the cryptogamegroup discussions over at Telegram.

Some research I did for this article:

Game Industry Timeline from 1997–2018

You can also check out my previous posts on blockchain:

Let’s Build A Decentralized Game Economy Using Blockchains

Crypto’s UX Challenge: Or Why The Blockchain Needs Game Designers

The Cryptogame “Hello World”: Make it Rain ERC20 Tokens!

Attribution:

All games mentioned belong to their respective copyright holders.

The icons from the diagrams come from The Noun Project, they have icons for everything!

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like