Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra returns from interviewing Magic Leap founder Rony Abovitz at the company's HQ to talk about how the much-hyped headset works and what it means for developers.

"Why can't we do the stuff we see in movies, in the real world?"

According to Magic Leap founder Rony Abovitz, that's the question that helped kick off the company's nearly decade-long journey to build a better way of looking at the world.

The result is Magic Leap One, a new wearable computer (comprising a wireless remote and a headset connected via cable to a pocket-sized PC) designed to spatially map your environment and create the illusion that digital objects are sharing it with you.

Many devs have been following the project since Google invested half a billion dollars in 2014 and now, roughly four years and over $1 billion in additional investments later, the company has released the "Creator Edition" of Magic Leap One. It costs upwards of $2,300, and could potentially jumpstart a new wave of mixed-reality game design.

Last month Gamasutra visited Magic Leap's Florida headquarters to try out the Magic Leap One and chat with the folks who work with it every day, in the hopes of providing some useful insight into how the hardware works and what you need to know to get a head start on using it in your own projects.

Prior to that visit, the question of what Magic Leap is was still pretty hard to answer. The company had worked in comparative quiet for years, with only an occasional funding announcement or glowing hands-on article to remind people it existed.

But by the time I flew out last month, Magic Leap had begun broadcasting dev-focused livestreams in which staffers tried to showcase the One hardware alongside tech demos illustrating its Lumin OS and how a Magic Leap game might look. The demos were simplistic, a far cry from the promo videos the company put out years ago. After watching them on my way to the company's office, I was expecting a disappointing tech demo.

I was wrong. The Magic Leap One headset I messed around with for a few hours last month seems to match up pretty well with what the company was pitching years ago. Within the controlled conditions of the Magic Leap offices, moving no faster than a slow walk, the One performs remarkably well: it's comfortable to wear, intuitive to use, and most importantly, it didn't make me want to puke.

In fact, I felt no discomfort or dislocation when putting on or taking off the headset, which immediately sets it apart from just about every VR device I've ever tried. Much like Google's Glass headset, donning the One is like slipping a pair of translucent glasses (or in this case, goggles) over your eyes; unlike Glass, there's no sense that you're switching focus when your eye moves from looking at something in the real world to looking at something digital.

"I came out of biomedical engineering and the idea was, don't break the brain. Don't break the brain is the number one rule."

Instead, digital objects seem to coexist in the world with you. When I put on the One there was an initial scanning period whenever it detected a new space (if you change rooms, or just move things around a lot) during which it would direct me to look at different points around the environment for a few minutes to effectively map it (Magic Leap staffers call this "meshing"), and thereafter it could create the illusion that digital objects were coexisting with real ones remarkably well.

It seems to do this not by projecting anything into your eyes, or out into the world, but instead by projecting a signal onto the Magic Leap lenses (which are actually custom photonic wafers manufactured on-site) that then gets pulled into your eyes alongside the rest of the world's visual data.

What this looks like, in my experience, is a sort of translucent virtual world of audible digital objects that can interact with you in near-real time. However, much as with Microsoft's HoloLens, the objects are only visible within a virtual window in the center of your vision that's roughly the size of a Nintendo Switch held six inches in front of your nose.

"We know we can make it bigger," Abovitz said when I asked him about the limited field of view, which is noticeable but easily ignored. "We already have. In our early prototyping for Gen 2, we've already done some amazing things."

This sample indicator .gif (pulled from a Magic Leap dev doc) gives you an idea of the headset's digital FOV

The technical details of how Magic Leap works are still somewhat unclear to me, even after hours of using the headset (in controlled conditions) and talking to folks who work on it. It runs on its own operating system, the Lumin OS, designed to either multitask (via what Magic Leap calls "Landscape" apps: put a lo-fi hip-hop 24/7 YouTube video on the wall, put an email client on your desk, have the basketball game playing on your coffee table) or take over the user's entire environment for "Immersive" apps like games.

By now you can probably learn a lot about it by accessing the dev documentation and downloading the Lumin SDK via the company's Creator program. The company has also published a list of suggested dev machine specs, as well as a starter's guide to developing for Magic Leap.

But when I was there I hadn't looked at any of that, and the most common answer I received about how it works was actually an analogy: it's sort of like a cotton candy machine, if the cotton candy was your game.

"Obviously there's no actual cotton candy involved, but think about the sugar being the content you create," said Abovitz. "It gets processed here [pointing at a small black box on the headset called a spatial light modulator] so it's like this thin line, kind of like how a cotton candy machine sprays a little thin line of sugar. And then it gets pulled and stretched across this wafer [pointing at the lenses] and it comes out as this volumetric digital lightfield signal."

According to Abovitz, this means that what's displayed through the Magic Leap headset is in some sense only fully understandable by the human eye; if you position a camera to peer through the goggles, whatever you'll see won't be what's actually intended.

(Because of this, the various videos you see of Magic Leap One interfaces or experiences are produced by merging headset camera footage of the user's perspective with digital Magic Leap objects. A Magic Leap representative told Gamasutra that staff have tried to record videos with a camera pointing through the headset, but the result is a "very poor representation" of the real thing.)

"Our system is best understood by putting it on. We designed it so that the signal by itself makes no sense against any other sensor but your retina," said Abovitz. "We spent over a billion dollars optimizing this thing to hit the retina to induce all the normal flow. We didn't want to change biology, we wanted to actually use it as it is."

This is Abovitz's core argument for Magic Leap's value: according to him, it's a wearable device that shouldn't make people nauseous or uncomfortable because it becomes a part of the way you perceive the world, rather than overtaking it.

The goggles are branded Lightwear, the puck PC is a Lightpack, and there's a red version on display at Magic Leap

"Here's the part that's really hard to communicate: your brain is the coprocessor. We spent all of our money and eveything we're doing to send a signal for the human brain, not a camera CCD [charge-coupled device]. Not a monitor. Not anything else," said Abovitz. "The circuit only works when it's put on a person. You only know it works when it's on you. So it's not like I have a phone display that I can take a picture of to show people what it looks like. It's really the signal's interaction with the brain that allows all this to work."

It's a promising pitch for devs who have spent years fretting over the discomfort issues plaguing VR tech, and it was borne out by my hands-on experience. In the hour or two I spent trying game demos, creation tools, and utilities (think: web browsers and sports broadcasts) in the Magic Leap One, I never once felt dizzy or nauseous, even though I typically have a hard time in VR headsets.

According to Abovitz, this is the result of the company focusing from the jump on how to target the brain, rather than the eyes. He dismisses most modern 3D tech (from 3D movies to VR headsets) as being fundamentally flawed because it relies on stereoscopic trickery which fatigues the eyes and upsets the vestibular system, the spatial senses provided by, among other things, your inner ear.

"I came out of biomedical engineering and the idea was, don't break the brain. Don't break the brain is the number one rule. And going down that path, we took the longer and harder road," he said. "You could have built [stereoscopic 3D devices] in 1900, and people did. I call it a cockroach; it just keeps coming back."

Instead, Magic Leap is designed to change your brain's perception of the world by constantly monitoring your environment and injecting digital signals into it in such a way that your brain will interpret them as natural sights and sounds. The company likes to talk about it in terms of your brain visualizing a constant simulation of the world based on the lightfield, a term for the field of light (in both particle and wave form) you're immersed in at all times.

"Think of it like a GPU. It really is a GPU. So the world that you experience right now is built in your brain. The visual cortex is like a biologic VR. The world you experience, this is our thesis, is a biologic simulator that's fed by this tiny datastream that is a massive downsampling of this big analog stream [that is the real world]", Abovitz said. "And that's how all of us are. And part of the reason is that lightfield signal has been around for billions of years. The biology of humans goes back millions of years. So the brain has developed over millions of years of being exposed to this lightfield signal, and part of my thought is, don't break this. Do not screw this up."

Put more simply, the headset does three things in real time: it senses the world around it (including spatial environment data, gestures, ambient audio and voice commands), computes and displays digital illusions, and communicates wirelessly (via Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and AT&T's network) with other devices.

"I think of it as like our Apple 1. You could be a regular person and get it, but it was really built for people to hack and share and create."

In my experience, that allows someone wearing the One to do things like paint three-dimensional images in the air, play games which involve your surroundings (so enemies hide behind furniture or climb onto it), or open floating web browsers that can adhere to any surface and use them to watch live video. These experiences can feel intuitive and "real" in a way that VR experiences (at least for me) do not, because they interact directly with the world (at least in the eyes and ears of someone wearing the headset) and, importantly, can keep doing so even when you look away.

For example, while demoing a paint program in Magic Leap One I opened a floating palette of creative tools and selected a sticker tool which created a virtual sticker of some creature (a unicorn, I think) on any surface I pointed at. I turned away and, in the midst of a polite conversation with staffers, slapped stickers all over the room and the people in it.

As you might expect, there's something uncomfortably invasive about the act of putting something -- even a virtual object -- on someone else's person without their knowledge or consent. More on that to come. However, the stickers stayed exactly where I'd stuck them for the rest of the conversation, even as I looked away or moved around the room, making them feel "real" in the same way that the chairs or the people felt real.

I also noticed that the tool palette itself felt more "real" and believable than I expected, though it's tricky to explain why. At one point in a conversation I wanted to use the palette, even though I'd left it stuck to a wall behind me, so without looking I reached behind me to where I remembered it being, selected it with the Magic Leap remote, and snapped it around to hover in front of my vision. It only took a moment and it felt utterly natural, as though I was reaching behind me to grab something I'd left on the table.

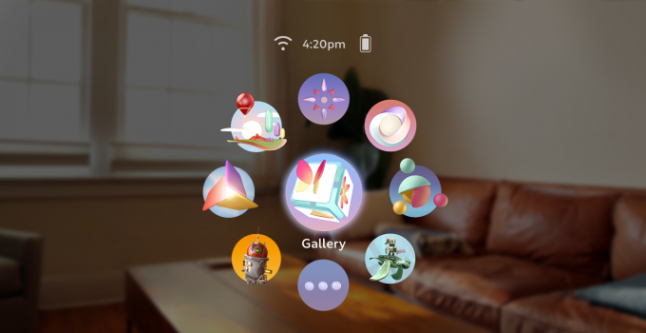

A promo shot of the Lumin OS (displaying a palette of apps) which matches up pretty closely with what I saw

This sensation of coexisting with digital objects is remarkable, and game developers should be excited about the possibilities of this tech. While I was at Magic Leap I played through a bit of the Dr. Grordbot's Invaders game project designed by the folks at WETA Workshop, and it's neat enough: wastebasket-sized robots bumble into the room through portals from another dimension, and the player zaps them with a virtual ray gun.

The enemies themselves move and look like believable robot goons, but what's notable is their spatial fidelity: when one moves behind a couch you can see its tiny feet peeking out beneath, and spot the dome of its head popping up around the edges of the cushions. You'll also hear it stomping around, and if you turn and look at something else you'll still hear it fumbling around the couch behind you.

It's an impressive demo, albeit one that's been in the works for years. Abovitz acknowledges that most devs will have to spend a lot of time working with the headset and the Magic Leap dev tools to create something of similar fidelity, and he's quick to call out this first edition of the hardware as something designed for early adopters and tinkerers.

"It's about soaking with people who want to create, build and share, so I think of it as like our Apple 1," he said. "You could be a regular person and get it, but it was really built for people to hack and share and create...and we have hundreds of people working on Magic Leap Two right now. So Magic Leap One is creator soak; get your hands dirty with it, take the next year, learn how to build, and learn how to be good at it."

Notably, Abovitz is frank about the realities of developing for Magic Leap in the next few years: devs should expect to be learning a lot of new tools and ways of thinking about game design, and they shouldn't count on having a big audience for their Magic Leap games. Instead, he encourages devs to learn the tools by making experiences that can be easily adapted for sale on other platforms, like AR-capable mobile devices. The Magic Leap storefront (branded Magic Leap World) is set up with a standard suite of monetization options, so devs can expect a range of pricing options, from completely free to free-to-play with micro-transactions to subscriptions (which feature an 85/15 revenue split, as opposed to the otherwise standard 70/30) to simple price tags.

"Be smart: publish for phones, publish for tablets. If you're really intelligent you can make something on a Unity or an Unreal or C code and build a world and publish multi-platform," Abovitz advised.

This seems like good advice given how some devs have suffered for investing heavily in VR game dev, only to see VR game sales hamstrung by the (relatively) low number of high-end VR headsets in the market. Magic Leap One's remarkably high asking price all but ensures it will be limited to enthusiasts for the foreseeable future, and Abovitz is upfront about that fact.

He cautions devs that getting in early means getting in when there probably won't be a large enough userbase to justify you making purely mixed-reality experiences, so you'd be wise to either focus on multi-platform games or on working somewhere that's large enough to absorb the cost of developing for new hardware.

"You could figure out survival strategies where you make a great hit, it's using ARKit or ARCore, and its relevant on Magic Leap, and it could be relevant on VR. And maybe there's some Magic Leap-only titles that come out, but there's clearly a strategy for the smartest and best," Abovitz continued. "[And] I'd say the big studios and creative networks that are coming together, they need creative brains, they need people who understand how to do this. So if I was an indie developer I'd be all over this right now, I'd be building up my talent set. This is totally different than making film or TV, totally different than building a game for an Xbox or a computer."

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

An example of how a game's store page (or "Diorama") appears in Magic Leap World

To help jumpstart the platform the company is helping to fund development of some Magic Leap experiences (like Dr. G), and Abovitz expects to continue doing so as the platform expands and better versions of the hardware and software roll out.

"Our next few years are about being massive supporters of the wide creator community, and then picking the gems we like and supporting them in a lot of ways," he said. "We want to support all devs with tools and as much support as possible, but the gems, whether they're indies in a garage or top film directors and musicians, we are already doing co-production and co-support projects. So we do everything from 'here's a unit' to co-funding stuff we want to exist. We want to spur this whole cool ecology of creativity."

Some of those experiences will be exclusive to Magic Leap, if only because there isn't (yet) a lot of hardware on the market capable of rendering similar spatial virtual experiences. But (unlike some VR stakeholders) Abovitz doesn't seem to care very much about hoarding platform-exclusive experiences; he says the company is amenable to devs taking their Magic Leap games to other devices, if they can work out a way to effectively port them over.

"I think we're doing some incredibly unique stuff, and so we'd want our platform to be the one of choice. But I'd say from a compatibility standpoint...we do think for developers and audiences, we want a level of inter-compatibility," Abovitz said. "I think it's important for the industry, and we're game to do that."

The question of how that might work has yet to be answered, but Abovitz seems eager to see what early adopters can do with the Magic Leap tech. He says one of the reasons the company worked to get Unity and Unreal support is to ensure the platform is approachable to develop for and, ideally, easy to port games to and from. In the future, he'd like to see Magic Leap experiences ported into VR and vice-versa.

"If you make something in Unity or Unreal you can publish across multiple platforms, but if I make this T-Rex and I have volumetrically captured my room and you're a friend in VR, why can't I pass that to you? And then you add in something to my room, and suddenly it pops there. Totally doable, we've built things like that," Abovitz said, by way of example. "Magic Leap, which we think of [in terms of] spatial computing and cinematic reality, can be compatible with simple things made for phones, simple things made for VR. It should. It's kind of a system, and the whole community has to stabilize, and then I think developers will push it. They'll come up with clever tools, and we want to support that compatibility."

Within Magic Leap HQ there's a palpable sense of anticipation, real or manufactured, for what developers will do with this technology. In our conversations Abovitz seemed keen to know what game developers might want from the company in terms of support, explaining that while "we know where it's heading, we also want to get that feedback from folks to figure out where they want to go."

And you won't be allowed to go everywhere; Abovitz says the company does have plans to police what's available on Magic Leap World with an eye towards ensuring nothing potentially harmful or disturbing gets into people's headsets.

"Our whole company, our business model is not about harvesting your data and selling it to people...it's an experiential computer, not a harvest-your-data computer. So it's really about getting the culture right. We realize we have to get developers and creators into the right mindset."

I asked about this a lot since people can be affected by your Magic Leap experience whether they know it or not: I was able to plaster someone in virtual stickers without their consent, for example, and you can imagine what users will do with the ability to draw 3D objects around other people in the same room.

Abovitz says the company is anticipating this and, at least when looking at developers' submissions, aims to abide by something he came up with at Mako called "The Mom Rule": effectively, if you wouldn't let your mom interact with it, it shouldn't be on Magic Leap.

"My mom will literally get mad at me," said Abovitz, whose mother was an early tester (back when Magic Leap was doing more traditional augmented reality apps) and actually appeared in early investor videos. "So it's a literal and metaphorical rule."

More specifically, Abovitz claims to be "bullish on the user" and says the company wants to give people "as much control over and transparency about what's happening" as possible, including how their data is being used.

This is an important point because the sensor-studded headset can collect all sorts of information about you, including (but not limited to) your voice and face, all of your activities, where you're looking, what you're doing, how you're feeling (by observing facial expressions and other biomarkers), the layout of your environment, and more.

"Our whole company, our business model is not about harvesting your data and selling it to people," said Abovitz, when I pressed him on this point. "We're doing [the] Creator launch first because we want to soak with creators and developers and say, the whole model here is not to grab the data from the person and treat them like something to be harvested. You want to think of them as a person. And how do you make their experience better? So we want people to have an amplified experience through life, whether it's in the morning having breakfast, taking a train into work, running outside one day, [we want to take] every single one of those moments and amplify them. It's an experiential computer, not a harvest-your-data computer. So it's really about getting the culture right. We realize we have to get developers and creators into the right mindset."

He says Magic Leap also has a dedicated quality control and safety team which has helped determine the platform's performance limits and ensured it complies with safety standards set by the FCC and UL (Underwriter's Laboratory, a product safety certification organization). While it's possible some people could have bad experiences with the Magic Leap One, Abovitz believes the company has done enough to ensure the headset is safe and comfortable to use.

"I think some more enlightened manufacturers try to make it so you can't put their headphones at a volume that hurts you. We try to do the same thing with our signal. And we've done a lot of testing, I think, about how you keep everything on the safe end of operation, but still give people some parameters and control," he said. "But we're going to pay close attention to what happens when we're out there. You have to be very sensitive to like, any kind of feedback from people."

The company is planning to host its first dev conference this October, and while Abovitz is eager to see what creative types of all stripes do with the hardware, he seems especially interested in how, exactly, game developers will bend and break it.

"Don't be burnt by VR."

"I think game designers, small teams probably in the beginning, will be able to do fast and quick hits. We're seeing things like, maybe 3-10 person teams can do really awesome stuff," Abovitz said. "And you learn what's fun, you follow the fun, you understand some cool new mechanics, and I think you'll begin to see....like the Weta team was doing a test to see what could triple-A feel like, with Dr. G[rordbort's Invaders]. It's not full triple-A, but I think it's the beginning of that."

From there, Abovitz expects devs to experiment with all sorts of different virtual worlds layered over the real one. The current Magic Leap One seems to struggle with any space larger than a room, but he says they've already had headsets talking to one another in the same space, and future versions will be optimized for both indoor and outdoor spaces.

At one point near the end of our visit I quickly demoed a sort of 3D basketball game visualizer, in which I was able to point at a surface and see a 3D replay of a clip from a recent game. It seemed like a neat way to watch sports, and Abovitz sees a near future where similar options are available for watching eSports matches play out across your coffee table.

Past that, he hopes to see devs pushing the limits of the tech to build shared virtual worlds, even as he acknowledges that there will almost certainly be a few years between Magic Leap One's debut and the existence of a large, vibrant audience of Magic Leap owners. The company is counting on interest in and passion for the platform outweighing the (justifiable) cynicism many devs might have after weathering the VR market's transition from boom to slow burn.

"Don't be burnt by VR," Abovitz said at one point, after I suggested some devs might be leery of jumping in early on Magic Leap or any other new "-reality" tech. "Don't just look back. Be smart, follow what's going to happen, but don't miss it."

Stay tuned for more from our visit to Magic Leap later this week, including some insight from the company's hardware and software leads about what game devs should know when developing for Magic Leap One

You May Also Like