Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Using Google Stadia and Nvidia Geforce Now as building points, Neil Schneider highlights opportunities for getting more game developers on board with the client-cloud industry. Supplemented with a new ecosystem report accessible by all.

The past few months have been a bold eye opener on the potentials and challenges of cloud gaming. The excitement is there, the vision is there, the technology is definitely getting there, and yet a new reality has taken hold which the industry will now have to come to grips with when charting forward.

There are several reasons why cloud gaming products (note the word "products" and not "industry") continue to earn excitement with every release: instant delivery, a huge drop in the upfront costs for gamers, premium level gaming quality at a whim, countless platforms being simultaneously supported, and the opportunity to bring premium quality games to far wider audiences than ever before thought possible.

While there are multiple players in the space now, I’m going to focus on Google Stadia and Nvidia’s GeForce Now because together, they underscore an opportunity to be realized as an industry.

First up is Google Stadia. Even though it has the standard latency challenges like pretty much every cloud gaming platform out there, it’s been technologically well received. Its biggest criticisms are that their gaming library is relatively small, and the startup and monthly subscription fees are too high. While I personally never took this concern too seriously because I figured the right marketing mix would come out in the wash as things moved forward, I soon realized there is more to this than how much people are willing to spend each month or to get started.

Next we have Nvidia’s GeForce Now (GFN). Brilliant product design. While I can’t speak for whether one is technologically better than the other, the media and the gamers seemed to eat this up because the only gaming library you need to worry about is the one you’ve already bought and plan to buy through Steam – provided Nvidia supports it. GFN is not a PC gaming store, you don’t have to repurchase your games, and the monthly fee is inexpensive in exchange for a premium gaming experience. Has a winner been declared? Keep reading.

The unexpected happened with GFN: several leading game developers pulled their best titles out of the Nvidia GeForce Now platform. Some said that Nvidia didn’t ask their permission, others complained about license agreements, most didn’t say why – they just wanted out.

Media and users thought it bizarre because gamers are buying their games anyway, who cares which computer it’s running on? I too couldn’t believe it because Nvidia is the tops when it comes to their co-branding with game developers and their developer relationships – they just are. What could possibly motivate these prized relationships to just walk away from Nvidia’s new flagship product?

Let’s go through that checklist again with both the Google and Nvidia cloud gaming products. Instant delivery of games? CHECK! A huge drop in the upfront costs for gamers? CHECK! Premium gaming quality at a whim? CHECK! Multiple platforms being supported? CHECK! All good, right? We missed one.

A major challenge with cloud gaming is the relationship between the graphics add-in board (AIB) and the gamer is one to one. It’s not enough to have powerful computers in the cloud; you need to have enough unique GPU processors to account for each simultaneous user. Too many users, and they have to wait their turn.

Another factor is users want more and more and more. Imagine what it would take to refresh every graphics AIB in a datacenter serving millions of people so that they could enjoy the next generation of gaming ability. Just think about that for a moment – what would be involved to get a series of data centers working with the next generation of graphics hardware?

Last month, Nvidia announced that they reached a million users. Free or otherwise, users all the same – and it’s a very impressive number. Remember though that gamers can’t all be on at the same time and that users need to connect to data centers in different parts of the world to get the best results; effectively thinning the potential compute resources by region. As Nvidia’s membership grows, so do their costs – they either need to have more GPUs warm and ready, or they need to restrict access. It’s one or the other.

I expect these factors are exactly the same for Google and for Sony and for XBOX and for everyone else looking to get into this exciting and deserving world of cloud gaming.

According to Jon Peddie Research, worldwide high-end graphics AIB sales including all brands is about three to five million units a year. I would estimate that there are anywhere from 15 to 20 million cream of the crop hardcore gamers who always buy the latest games and gear. Sure there are more mid-range, but I’m talking cream of the crop.

Now let’s get back to that missing checkmark: the opportunity to bring premium quality games to far wider audiences than ever before thought possible. This is where the models run into difficulty.

In the cloud gaming world, I theorize that the developers are faced with a very difficult choice. The Google model is likely “we’re going to get subscribers, and we’re going to pay you as these subscribers come in”. The challenge is gamers are already sold on other platforms, so the co-marketing and publishing cheques have to be lucrative, or the endeavor needs to at least attract enough new revenue to be worthwhile. This has probably contributed to Google’s slow and steady library growth – Rome wasn’t built in a day.

In contrast, the Nvidia model is “we’re going to get users to buy your games on their own, and we’re just going to charge them a nominal computer rental fee so they have what to run your games with.” The thing is out of those one million GeForce Now users, how many are new game buying customers that wouldn’t have otherwise been there anyway? I’m thinking very few. Could this model also create a game developer risk of losing sales opportunities with alternative publishers and vendors that are willing to cut the big cheques for the same content rights?

So sure, the user is just using another computer with a game they legitimately bought – it sounds simple enough. The challenge is that in this case, the game is the product that the cloud gaming services are being marketed with – their game is the actual product benefit. If the game developer isn’t getting new product sales revenue, then it stands to reason that they want compensation from cloud gaming vendors for using their games to market vendor products.

If we limit ourselves to the perspective of lone cloud gaming products, two solutions come to mind:

Solution one is time. As long as cloud gaming vendors are willing to invest what is necessary for the audience growth, cloud gaming will develop outside the confines of the pre-existing games community. If there is a way to appeal directly to new users instead of what already exists on PC and console, that would be even stronger and translate to new sales for game publishers. If it’s obvious that these cloud gaming services are reaching new audiences, then the hurdles of special exclusivity deals and the custom licensing agreements become far less important. I don't know what that threshold of users is, but I'm sure the industry will reach it.

The second option is to sponsor the game developers up front or include them in some kind of blanket licensing agreement for a cloud service provider. Be prepared though that if the exclusivity door is opened wide, we could end up in a world where user cloud gaming choice will also determine which games are and aren’t in their library. Imagine only being able to play Call of Duty one and two on Google, Call of Duty three and four on Nvidia, and Sony and XBOX are busy fighting over the rights for the rest of the series. Who does the user choose? Maybe it’s just no longer worthwhile for them. Also, where does this leave the smaller data centers that also carry valuable audiences? Are the developers missing out by only getting a portion of the market potential? Things to consider.

If we start looking from the point of view of an industry that cloud gaming lives in, the options get even more attractive and strategic.

PC and console may indeed carry more processor-intensive experiences compared to what cloud gaming delivers over the long term. I say this because if Jon Peddie Research is right, major cloud architectural innovations will only happen every four-plus years or so. The reasoning is that it’s very expensive to retrofit all the datacenters on a regular basis, and the sales cycles that support the R&D for rapid 24 month innovation on PC aren’t the same for cloud. I think this is a good thing because there has to be a place for the premium gaming community to go while other users fall in that “good enough” crowd – assurances that audiences are not overly duplicated across each choice of computing platform.

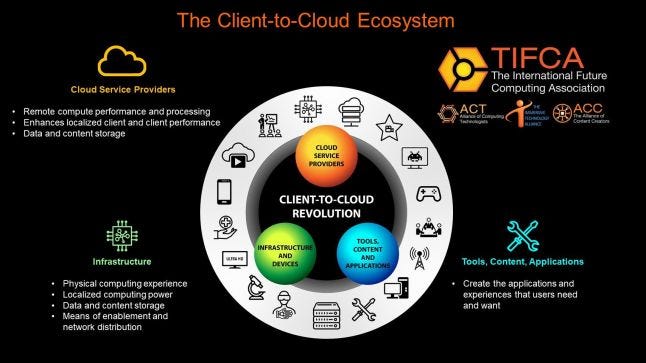

Next, I'm looking forward to an inclusive trifecta of compute solutions. Localized compute which we use today, the all-important cloud gaming options for the thin clients out there, and finally a truly collaborative client-cloud processing system combined with a create once, reach all mechanism for content and application creators.

The premise is that the cloud enhances the abilities of individual client devices like PC, mobile, and console so that they are capable of doing more than what they are built with, it frees up bandwidth and improves infrastructure which equally benefits the 100% cloud-centric services, and with all computing options combined, this brings in a wide scale of new customers and gamers that were previously inaccessible for everyone.

The big question that remains is does the industry want to see this computing era happen?

The International Future Computing Association brought the client-cloud ecosystem together at its International Future Computing Summit last November to learn from one another and to go through a self-discovery process of what to enable next. Each year, the summit is a strong cross-section of compute and compute platforms, immersive technology, innovative content and applications, and networking infrastructure like 5G.

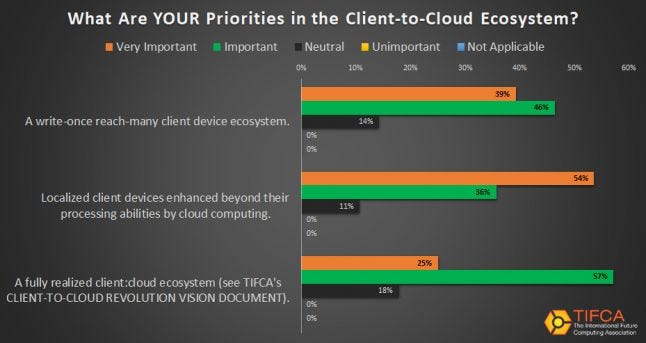

After the conference, a questionnaire was completed by roadmap level executives working across the client-cloud and future computing ecosystems. All the results have been published at http://www.clienttocloud.net along with other support presentations and data. SPOILER ALERT: the results were positive, and work is already underway to get ready for the next IFC Summit this November.

Between the questionnaire responses and what we are seeing in the industry, the importance of the next era of computing is clear – a journey we’ve been calling the Client-to-Cloud Revolution. The industry needs a strong and defined ecosystem for cloud gaming to live in because it’s important, it needs to widen the potential audience for application and technology makers alike through new client-cloud ecosystem channels, and it needs a create once, reach all mechanism for innovative content and applications developers because their customers want the best experiences on everything they are running.

The good news is there has been follow-through since last year’s International Future Computing Summit and the industry is regularly gathering in TIFCA to propel this vision forward. We are also running a future computing presentation series and Client-Cloud ecosystem workshop at the Realtime Conference this April - would be great to see you there.

We all have an exciting journey ahead. The best is yet to come!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like