Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Sonic the Hedgehog character designer Naoto Ohshima expounds upon the early days of Sega's mascot, recollects design choices in the Saturn game Nights, and explains why it's important to make games that are "just a little new."

When the secret history of video games is finally written, a special chapter will have to be devoted to Naoto Ohshima. He played a crucial role in exploring the creative possibilities of new console technology by working on some of the most innovative titles of the 1990s.

After contributing to early installments of Wizardry and Phantasy Star, Ohshima created the iconic character designs for Sonic the Hedgehog. The blue mascot's success paved the way for Ohshima's directing turn on Sonic CD, a game brimming over with fresh ideas that few had an opportunity to experience due to the Sega CD's unpopularity.

His next major project, Nights Into Dreams for the Sega Saturn, was an audacious and beautiful attempt to claim the high ground during the early days of 3D console gaming. He followed Nights with Burning Rangers, another game for the ill-fated Saturn that was radically different from its violence-oriented 3D contemporaries.

As the 90s came to an end he weathered the shifting fortunes of Sega by forming Artoon, developers of Blinx: The Time Sweeper, Blue Dragon, and Yoshi's Island DS, and now heads the sometimes brilliant, occasionally aggravating, always interesting Cavia -- recently responsible for Capcom's Resident Evil: Darkside Chronicles, and currently working on Square Enix's upcoming Nier.

You recently became the CEO of Cavia, moving over from Artoon -- or is it more complex than that?

Naoto Ohshima: Well, the head of the company here quit because of... family issues. (laughs) Since they then lacked a president, I sort of wound up taking over that role, since we're all technically part of the same outfit. (Ed. note: Artoon, Cavia, and Feelplus are all under AQ Interactive.)

I do like a lot of Cavia's games. Though they often seem unpolished -- the games seem to get "almost there," do you know what I mean? Bullet Witch and Ghost In The Shell: Stand Alone Complex both have something to them, but these certainly don't feel like Ohshima-style games.

NO: Well, certainly, I do a lot of management-type work these days. I definitely want to make something again! I really do.

Your first major console game with Artoon was Blinx. You might say it was ahead of its time... games like Prince of Persia used a time mechanic long afterward and saw great success with it. Where did that idea come from?

NO: It was purely a product of the hard drive included with every Xbox -- the original one, not the 360. We wanted to build a console game from the ground up that used the drive effectively.

That's where the play mechanic came from?

NO: That's right. There wouldn't be any other way to do it. The PS2 wouldn't have been able to do it.

Do you think it would be possible to make another mascot-style platforming game in the current era?

NO: Ah, well, I'm making a game like that right now. (laughs) I can't quite talk about that yet, though. In more general terms, the game needs to be something that anyone is able to play, and it needs to have one thing or element that is brand new, that hasn't been done before.

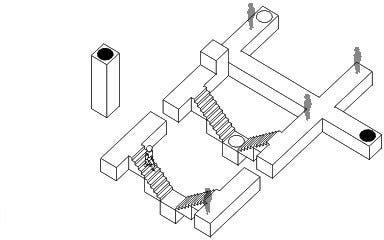

Nights Into Dreams

Nights Into Dreams on the Saturn was the first really 3D game I played, long ago. As the Nights character you had a certain path you followed in 2D, but if you went back to human form, you could walk around anywhere you liked. I found a lot of things that way that I couldn't see as Nights, and it was a sort of turning point for me; it felt like a real-life world to me, making these discoveries. You don't get that pure feeling of discovery much in games anymore. Was that something you were purposefully aiming for with Nights?

NO: Well, with people my age, we didn't really have video games as children. When we came up with concepts for games, we couldn't say "It's some of this game and some of that other game." As a result, especially around that era, you had a lot of games that did not become truly evaluated by the public until long after their release. There just weren't a lot of 3D games back then.

Of course, with Nights, if you keep going and going along the ground you eventually run into an invisible wall, so... we had to think about ways to keep players from going that far off; that's where the Alarm Egg came from (Ed. note: a wandering alarm clock that follows the human player and wakes them from the dreamland, thereby ending the level).

BS: What made you want to put features like that into the non-Nights section of the game?

NO: Well, the original inspiration for the game was to create a Peter Pan-like character. Nights and Peter Pan share that character trait; they're both capable of things that regular people can only do in their dreams. So I wanted two games here, in a way; one where you were human, and one where you combined with Nights to accomplish extraordinary things.

Nobody had really played a full-on, free-running 3D game at that time, so we were concerned that people would have trouble comprehending the game if it gave you complete control freedom. As a result, as a human, you have freedom, but only in a small, confined space. Combine with Nights, and the game switches to a side-scrolling type, as gamers would've been readily familiar with at that time.

In a way, having a vulnerable human character able to do things Nights couldn't is somewhat empowering to the player.

NO: I agree.

Christmas Nights was also ahead of its time -- the idea that you could unlock extra stuff depending on what the date is. Those sorts of games are still rare to see.

NO: Indeed. That game is mostly the same as Nights, but it was very literally a Christmas present for our audience, a sort of thank-you from Sega to its fans. That was the concept.

I was an enormous fan of Sega, around the Saturn and Mega Drive/Genesis eras, and that certainly calls to mind the Sega of old. What struck me about Christmas Nights was that there was a lot of stuff in there, altered graphics and such, that would only be playable for two days' time.

NO: We had the idea to have Spring Nights, Summer Nights, and so forth, reflecting all of the seasons. It really wasn't a technological challenge, as the textures don't really change much. It didn't take a lot of time, and I think its mission of drumming up interest and excitement among our fans was pretty well met.

What did you think of the new Nights?

NO: The Wii one? That project was led by [Takashi] Iizuka, who was the lead designer on the original Nights. He really loves that character, and I'm sure that he was able to create the Nights that he wanted to create.

It didn't feel the same to me.

NO: It was, perhaps, more Americanized than before. The original Nights was chiefly made with the Japanese and European audiences in mind -- Sonic, meanwhile, was squarely aimed at the U.S. market.

In what way did you position Sonic for the U.S. market?

NO: Well, he's a character that I think is suited to America -- or, at least, the image I had of America at the time. Nights is a more delicate... well, his gender is deliberately ambiguous, for one.

It's a cliched question, but was that why Sonic's main colors are red, white and blue?

NO: (laughs) Well, he's blue because that's Sega's more-or-less official company color. His shoes were inspired by the cover to Michael Jackson's Bad, which contrasted heavily between white and red -- that Santa Claus-type color. I also thought that red went well for a character who can run really fast, when his legs are spinning.

Sonic CD

You were also the director of Sonic CD -- another game that had time travel as a play mechanic. Have you liked that mechanic for a while?

NO: Well, I wanted a Sonic where the levels changed on you -- where Sonic would go really fast, like in Back to the Future, and bang, wind up in a different place.

Why do you think you've been involved with a lot of games with time elements to them?

NO: I hadn't realized that, actually. (laughs) There must be a part of me that likes that sort of thing, the time.

Sonic CD really felt great in action. It doesn't have the full-on speed of Sonic 2, but the world feels really alive in the game, much in the same that it did for me in Nights -- that feeling that the game world would still be alive even if I weren't exploring it. Was that your intention?

NO: Sonic CD was made in Japan, while Sonic 2 was made by (Yuji) Naka's team over in the U.S. We exchanged information, of course, talking about the sort of game design each of us was aiming for. But Sonic CD wasn't Sonic 2; it was really meant to be more of a CD version of the original Sonic. I can't help but wonder, therefore, if we had more fun making CD than they did making Sonic 2 [because we didn't have the pressure of making a "numbered sequel"].

What I really wanted to do was just have this sonic boom, with a flash, and have the level change on you instantly. We just couldn't manage it on the hardware, though, so instead there's that sequence that plays while it's loading. (laughs) I kept fighting and fighting with the programmers, but they said it just wasn't possible.

I bet they probably could have done it.

NO: I know! (laughs) If Naka was doing the programming, I think it could've been done.

Do you know why Naka left Sega?

NO: No, actually.

The way he put it, he was too far up -- he was doing nothing but management and couldn't do any design or programming work on games. He couldn't even influence Sonic anymore. I thought that was admirable that he went on to try to do creative work again.

NO: Indeed. In fact, it was really the same deal with me and Artoon. Now, though, the group as a whole has gotten really big -- it's sort of a mini-Sega.

So will you be making your type of game in the future, then, or are you going to be making more darker-styled games, as Artoon and Cavia have been moving toward?

NO: Well, the important thing is to make gamers happy -- the users playing your game. When you make something that's truly new -- well, it's not that you have to with every project, but when you do, you're expanding the world of games. That's what I want to do; I want to keep on doing new things, and I think that's possible with Artoon, Cavia, and Feelplus.

The way I see it, if the director makes the sort of games he wants to make, then the end results are going to be more interesting. The gamers are important, of course, but if you make a game for yourself, that adds character to the result.

NO: Well, for example none of my favorite movies were really hits. (laughs) Myself and the gaming audience, we're different. I like new things, but if something is too new, then gamers won't be able to comprehend it. So you have to think about your audience at least a little bit, or else you'll make something that runs the risk of being incomprehensible. That's why I want to keep them in mind.

Certainly that's true, but sometimes you see indie films become hits, too. Taking that risk is important, I think.

NO: Yeah, but the sort of indies that become hits are those that are easy to follow for anyone who watches them. So, in the end, you want to make it just a little new -- not completely so.

Echochrome

With games, though, you have download platforms that can support titles like Echocrome (the PSP version of which Artoon worked on). Games like that, they don't have to be massive hits.

NO: Sure. Echochrome doesn't have very fancy graphics at all, but play it, and it's really fun. It really depends on the game.

What made you decide to move into that darker territory with Vampire Rain and Artoon?

NO: Games are a part of the overall realm of entertainment, including movies and music and so on. I think that movies play a sort of big-brother role for the game industry. The Japanese film industry has been around for ages, but once films from other countries began to see wide distribution here, Hollywood films very quickly became the most popular.

Within that environment, Japanese animation has managed to attract worldwide praise, which is great. But we're seeing a sort of Hollywood-ization of the game industry right now, and Japan's traditional strengths in cartoon-style games are going by the wayside. So in thinking about the future, I realized I wanted to do both "real" and "cartoon" games. Now, Vampire Rain got a negative reception from a lot of its players, and we regret a lot of things with that game, so in the future we definitely want to make games that excite people a great deal more.

You could say that Silent Hill has succeeded at that in the past, showing an auteurism without being Hollywoodized -- opening up to the world on its own terms.

Those cartoony games do not sell well in Japan any longer, either -- it seems like platformers like Sonic and Mario are the only ones that do. Why do you think that is?

NO: Because they're all the same. The art and the storylines may be different, but the gameplay is the same.

Lately I've been thinking about how to modernize games like those. I think the first hour or so of Uncharted is close. You don't have a gun or anything -- you're just jumping around and searching for treasure in this gorgeous environment. I thought that was really fun, until it got to the shooting bits, but I'm not sure if such a game would sell well.

NO: I do have an interest in that sort of thing as well, but I think games that have more of an original idea to them come first in my mind.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like