Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Former Lionhead boss Peter Molyneux spills the beans on his inspirations and discusses what's going on with the evolution of the triple-A console industry he abandoned when he left his post as Microsoft's European creative director.

Peter Molyneux is notorious for overpromising -- for enthusiasm and bluster. Even knowing that, seeing him speak last month at Unity's Unite conference in Amsterdam was an experience. He was even more excited than he usually is to talk about Curiosity: What's in the Cube?, his first game -- or as he terms it, "experiment" -- with his new startup mobile developer, 22Cans. This interview was conducted soon after that whirlwind presentation concluded.

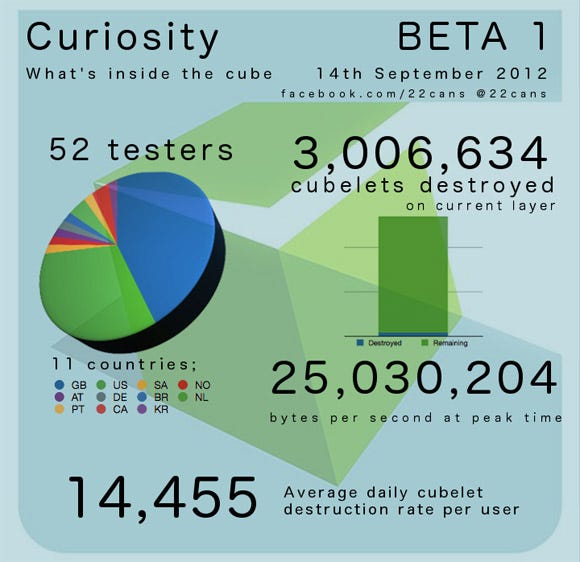

You can see why he doesn't call it a game. Curiosity presents all of its users with a single large cube made of small squares. Each square will disappear with the single tap of a finger. There are layers upon layers of these squares -- so many that Molyneux predicts it will take months for players to get to the middle. The person who taps the final square -- and only that person -- will get to see what's inside the cube.

The game is a prelude to whatever 22Cans is planning for its "big game", which Molyneux is closemouthed about. In this interview, however, he spills the beans on the inspirations and technology that he's looking at, as well as discusses what's going on with the evolution of the triple-A console industry he abandoned when he left his post as Microsoft's European creative director.

I guess what struck me the most about your presentation was that you were even more enthusiastic than usual -- which is kind of over the top.

Peter Molyneux: This is not me enthusiastic. I just tried to tone it down because it's so exciting, what I'm doing. It's amazing. It's amazing. To go back to those grass roots again, and to go and get your hands so incredibly dirty from fiddling around, and then be playful with all these crazy technology, and bring together a team, and try to persuade people to invest in you, is amazing. It's incredible -- an incredible sensation.

Do you feel like you were too far away from that creative place?

PM: No, no, not at all. Microsoft was an incredibly supportive place, and they really supported my creative idea. But the freshness of the approach -- you can be unbridled about what you approach, whether it be the Ouya -- "Oh, maybe I'll develop for that!" or whether it be "Let's use analytics in a different way." That is the incredible potency of being a startup.

There's also this incredible fear, because you can, of course, jump on any bandwagon, which may end up crashing and burning by the time you've jumped on it. But I'm incredibly passionate, and incredibly passionate about the team. Brilliant team.

You mentioned that you're recruiting from outside the game industry. I'm sure everyone's asked you about this, but what does that bring?

PM: Fresh perspectives. So often, in life, when you get used to do something one way, it's very hard to persuade your brain to do it in another way. Whether it be brushing your teeth from left to right, or whether it be "I write this sort of game," or "I design in this sort of way."

PM: Fresh perspectives. So often, in life, when you get used to do something one way, it's very hard to persuade your brain to do it in another way. Whether it be brushing your teeth from left to right, or whether it be "I write this sort of game," or "I design in this sort of way."

And if you're just trying to think in a different way, then having people around you who have never thought in a way that you've thought just means you're far, far more likely to discover something you didn't know existed.

Part of my belief is, at the moment, there's a lot to discover. There's a lot to discover about cloud, and persistence, and multi-device, and linking people together, and analytics, and a lot to discover about bringing them together.

And when you've got people that you're sitting next to who have never designed a game before in their life saying, "Oh, you know, I don't understand what 'leveling up' means." You'd never question that as a designer if you were working in an old place. It's that fresh perspective which is so fascinating.

Do you find yourself questioning everything because you're being exposed to questions?

PM: I think I find myself learning from everything that I see on devices like this. [indicates iPad] I'm realizing that learning causes me to question an awful lot. I mean, so much is happening in such a short amount of time! Free-to-play was going -- well, I don't know who invented it, but it was certainly used by Zynga. And then everyone said, well, free-to-play wouldn't happen, and then now it's happened completely, and now everyone is panicking that free-to-play is the only way that people will pay.

Analytics came along, and people like Zynga said oh we just hire people, you know analysts from the City [the financial industry], and we thought, "Oh, well that's that solved. You have to go and hire bankers." And then somebody realized, "Hang on a second, why don't we use analytics to balance the game after it's out?"

All this stuff is happening incredibly fast, and all these experiences are being pulled together, and all these audiences are coming up. And it's an incredible time -- an incredible time to work with people who have done everything from children's books, to scripts on TV programs, and bring them in, and get them to think -- and make you think in a different way about a game.

You alluded to using analytics not for just for monetization, but to actually improve the gameplay experience. Do you think there's a lot of work to be done there?

PM: A huge amount of work, yeah. Here's my thought, and it's quite a radical thought. This is my thought: at the moment I can see what analytics does for an awful lot of the games. It tries to get as much money from you as possible in the shortest amount of time. Fair enough. It will balance that level 19 just right so that you have to spend money to get to level 20. Fair enough. But what the developer is doing there is trying to think, "Right, we just know you're only going to play for a few hours, we just want to squeeze you for everything you've got."

Let's think in a different way. Imagine you had an experience; just imagine this insane idea. There will be a single day when I can give you examples of games in the past that are clues to this, but you will play for the same length of time that you watch [long-running British soap opera] EastEnders for.

EastEnders, people watched it for the whole of their life. They grew up with it, they got married with EastEnders, they had children with EastEnders, they'll probably die with EastEnders. We have nothing in the gaming experience which feels like it's more than just a 10, 15, 20 hour experience.

Imagine if we -- now, I'm just not giving you a clue that I'm going to create this -- we had something that was refined and curated just the right amount, to just the right number of people, to keep you engaged in the same way that you're engaged with a hobby? Why can't we have that?

Now maybe World of Warcraft, for some people, is what I'm talking about, but that's just for a small number of people. World of Warcraft wore me out. It just drained every piece of gaming life out of me. I didn't have anything left to give. So that was overcooked. But I think there's something in the middle. We have to surprise people. We have to shock people. Not by going into our ivory tower and thinking of another new game idea.

Tomorrow, for example, in the cube, I'm going to do this. We'll do this. On one of the surfaces of the cube, we'll have a really simple game with those little cubelets. We'll have, say, there's this mathematical thing called Life. One the surfaces will be Life. You tap on the right thing, and it will just all spread out. That will be a surprise. And that's done for the reason that we want to keep you engaged. Even if you just tap 20 times a day, if I can keep you engaged over a long period of time, that will be exciting.

Did I answer your question?

Yeah, you did. I get the sense that you see this massive potential, and other people have alluded to it, but it seems like, for one reason or another, people end up not realizing it. And maybe it's just a natural evolutionary process that games, as a new art form, have to get through.

PM: It's just a different way of thinking. I would love to have been in the kickoff meeting for [long-running British soap opera] Coronation Street, because it could have gone something like this:

The writers of Coronation Street come to the TV execs and say, "We thought of this television program. It will be number one or number two in the ratings every single day of the week for 40 years."

"Brilliant," say the TV executives, "that must be an amazing story. What, I can't imagine. What is it? It must be something like the works of Shakespeare?"

"No, no, no. There's no story."

"No story? How can anything last for 40 years without a story?"

"No, there's no story, It's just characters. It's just the same as the life outside people's windows."

I can imagine the TV executives were like, "No way it will work," because it was so new. It was so different to have a TV series about characters that lived -- were born, lived, and died in the street. It sounds the most boring thing in the world, but some people love and are entertained by that.

And if you think in that way -- if you think in a way that maybe there's one experience, in a way like Facebook, that I don't mind interacting with for years, and years, and years, that would be an amazing experience. It's just a different way of thinking. Don't think that I'm doing a cross between Coronation Street and Facebook.

That brings me to the question, actually -- is there a line between what's a game and what's not a game? There's a tremendous amount of debate, particularly on Gamasutra, about what constitutes a game, what that word means.

PM: The problem is, nowadays, saying "what's a game?" is like saying "what's a film?" or "what's a book?" I mean, if you were to look at the film industry and you only watched Saw movies -- Saw I, Saw II, Saw III -- and then I asked you to write an essay on what's a film, it'd probably be the most damning essay of human depravity.

On one end of the spectrum, you've got all the horrific nature of Saw, and on the other end of the spectrum you've got some of the wonderfully delightful sorts of movies like Star Wars that affected a whole generation. There's a whole huge range, and that's what this word "game" tries to encapsulate.

The trouble is, with "game", it's also what game people define games as, by a series of these cornerstones -- like a game has to have challenge, a game has to have story... And we have these colors, which we think we mix together to make a game. But now those colors are completely changing.

Because does a game, does a story, have to have an end? No it doesn't, if you're doing Coronation Street. It has a series of little stories. Does a story have to have a predefined beginning? Yes it does, but that leads to a boring film. And so I think a lot of those rules are changing.

One of the most important bits of game, or so a lot of people think, is decision-making. But then people point out the fact that some of the social games don't actually require much decision-making. It's actually more of a task list.

PM: I think decision-making is of paramount importance in certain games, yeah. And you can boil down a person's activity into decision-making if you particularly want to. Is there a lot of decision making in the Half-Life series? It's a corridor-based game. There's one way through. Well, you could say you do decide...

Tactical decisions.

PM: Yeah, maybe tactical decisions, but then I think you're trying to take what is a simple word like "decision-making" and trying to fit it into lots of different buckets. Is there decision-making in The Sims? Yeah, but it's much more complex decision-making. Or an RTS? Much more complex. So it's a very simple term, which you're trying to fit into lots of these other terms.

I found it very interesting that you said the idea of simply making a game and putting it out is over -- as you put it, "the idea of handing down an idea is over." Essentially I think what you're referencing is working on a console game for two years, and then putting it out in a box is over.

PM: And you go on holiday.

Do you really believe that it's over?

PM: I do. It's over. It's over. It's unthinkable to me experiences -- that it's so easy to get feedback and continue to refine -- that we wouldn't do that. Why would we not continue to change and tweak it? Now, I'm sure there will be exceptions, but if you have the ability to look at what people are enjoying and what they're getting stuck on, and the ability to change that, why wouldn't you change it? Of course you would.

With Curiosity, there's this degree of players collaborating, but sort of competing too. There's this push and pull. That really interests me, that way of looking at multiplayer. Can you talk a bit about that?

PM: The multiplayer encompasses the whole world. When we're all -- I couldn't show on stage because we didn't have enough people on the cube at the moment -- when you actually see thousands of people play, it's an amazing experience, because people collaborate. They do things together. They get the idea.

At the moment, in the cube, you can't text. All your ideas have to express through the space, which is quite interesting. And of course, people will collaborate, but ultimately it comes to, there's going to come a point when the cube gets small enough where people start realizing, "Shit, there's not long to go. I don't know if I want to collaborate anymore because only one person is going to find out what's in the middle." And the number of taps required on the last surface will be the number of active users, so everyone will get one tap, and that's going to be frantic.

Wow.

PM: And this will be so interesting, to see what people do. They may just give up, or they may just tap obsessively, or they may just want to find out what's below each surface.

Or 4Chan might try to organize and grief it.

PM: Cheating is a real problem for us. We were worried about cheating, because someone could write a bot -- someone actually said they're going to have one of those dipping birds, and just put them in front of the key, and have it just dip away. [laughs] It's not really feasible, because it would have to dip and scroll.

Someone could do something with scripting, though, potentially.

PM: It's difficult. It's difficult. We have had to think about that, and obsess about that a bit, because it could be that we just put it live and then 24 hours later, see this cube just shrink down in front of our eyes.

Well also there's the idea that things are going to emerge once the game goes live that you're not anticipating.

PM: That's why it's called an "experiment", because we can't pre-think this stuff.

And do you think that that's going to influence the direction you take with the different layers?

PM: Yeah, for sure. The different layers, and the final game that we're making. There's enough layers that we can adapt the experience. My prediction is that it will last for quite a few months, and that means we have time to adapt the experience accordingly.

You talked about the idea that you're working on a big game -- a quote-unquote "big game." I don't know what that means, and it probably doesn't mean what it used to mean to you.

PM: It's big in its ambition. It's huge in its simplicity. And it's on a massive scale. Not on a massive scale as in you know, it's a triple-A game that takes 20 to 60 million to make, but it's on a massive scale because it's an idea for the world. In the way a bit like the cube is an idea for the world. But the cube isn't a game, as such. Well, that's why it's called an experiment. It's an experience.

Do you think that maybe ambitious ideas are now more important than big experiences?

PM: This is going to sound a bit philosophical. Maybe I'm just a bit tired, and I get a bit emotional when I'm tired. But whenever mankind is faced with these huge challenges, it always comes up with big ideas that change the world. Whether that's the industrial revolution, or the spinning jenny or whatever it is, or how you use steam, or how you use electricity.

But I think that these things now [taps iPad] are great pieces of hardware. There just aren't great pieces of software to match those pieces of hardware, and history proves that a vacuum is always filled. Something will fill that which really amazes us. There's nothing that defines this, in the same way that consoles were defined by certain gaming experiences. So I think there's just loads of space for innovation.

I wanted to talk to you, also, about how you arrived at the idea of focus, and focusing on simple concepts.

PM: Just through the atrocious mistakes I've made in the past. Being at Microsoft, I was helping to design Fable: The Journey, and I was also going around all the different studios in Europe, and I was also the studio head of Lionhead, and I was also doing all the PR, and I was also an exec at Microsoft, and I was also looking at the new hardware stuff.

And I just personally can't do a good job on more than one thing. If you believe that you've got an idea, you believe that that idea is worth throwing all your chips back on the table and betting them all over again, then that should be your single obsessive focus, I think.

While you're talking, I was wondering if maybe these massive productions -- Fable-like games that cost tens of millions of dollars -- have maybe pushed things too far in certain directions and become unsustainable?

PM: I'd hate to think they're not sustainable. A lot of the brilliance of how Unity is developing is because Unity aspires to be the tool that will eventually create those sort of games. And I think it's incredibly good for triple-A games to push the quality envelope of where we are.

I just think that triple-A games need to adapt, just like any other genre. They need to adapt, and they need to embrace this new tidal wave of multi-device, analytical, persistent, cloud computing universes that we've put forward.

And at the moment they don't feel like they're being adapted, partly because they're squashed by the hardware evolution. I mean, Apple comes along and iterates on its hardware every six months. It takes us, in the console manufacturers, six years. By the time another console generation comes out, God knows, it'll probably be in your brain or something. That's part of the problem. But it'd be great.

I'm absolutely sure one day, development on a title on this is going to go up in the tens of millions. You can already see development like Infinity Blade. And there's going to be more of those -- and all those texture maps and animations and all that stuff, it costs money.

I've got a two-sided question. Now that you're outside of the Microsoft console world, what is holding that back? You did allude to the hardware, but what is holding that back from jumping feet first into these sorts of things you're talking about?

PM: For development?

Yeah.

PM: Well, there's two big problems. One is, making an existing triple-A game is incredibly hard to do. Insanely hard to do. Whether it be Call of Duty or whether it be a new franchise. It's insanely hard to do. To do all that stuff and to totally embrace this new, disruptive world is, it's doubling our efforts.

Quite often a publisher or whatever will turn around and say, "Oh God, I wish you supported achievements better," or, "Could you support Live more?" But it's not something that you want to have ordered on. You want to get those teams to get obsessive about it. And doing those two things together is very, very, very, very difficult. It's very difficult.

And the other side of the coin is, now that you're in the startup world, small team, you talked a little bit ago about that there isn't a game that pushes this device in the way you see its potential. What's holding that back?

PM: Well again, it's the same problem. There's just a hell of a lot of stuff to get used to. For us existing, very unfit developers, who have been in the safety of the triple-A universe for a long time, we need to get fit again. And for anybody coming new, there's so many different things going on so quickly it's hard to focus on what one.

Now it's all settling down a little bit, and we totally realize that cloud is here to stay, and cloud computing is here to stay, and analytics is here to stay, and multi-device is here to stay, we can start settling down on that. I hope. But you're starting to see some real enhancements in things like free-to-play already. It doesn't feel so greedy anymore.

We've been through a lot of evolution over the last few years in the industry, in general, and we've seen a lot of things change. Well, there's no end state, but you don't know where we're going. Or do you think you have an idea?

PM: No, I don't know where we're going. I just know we're going somewhere new. This is the best analogy I've got. What we do is like exploring a new country. It's like going after the source of the Nile.

We have no idea what's around the next bend. It could be a cliff, it could be a pit of crocodiles, it could be a path with a big arrow on it. But it does feel like, sometimes, you've got your machete out and you're beating through the unexplored country. But we know we're going somewhere. We definitely know we're going somewhere. We aren't quite sure the route we're going to take there.

And where we're going, I think, is that we're going to fulfill our potential. And our potential is a true, true, proper entertainment medium, a true entertainment medium. The first ever entertainment medium that engages people, that doesn't demand that a person sits there and sucks up information like a sponge without any form of feedback, and engages people. That's the real invention that we're going to, and that's an amazing invention. That's true democratization of entertainment, not just of development.

That's way too passionate, isn't it?

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like