Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Texas Independent Game Conference, held on July 22-23 in Austin, rallied indie developers together to wage war on the mainstream. Gamasutra was there to get the scoop, in this exclusive recap!

The troops are mustering. The plans are in the works, and the lines are drawn. Get ready for war.

But don't forget to have fun.

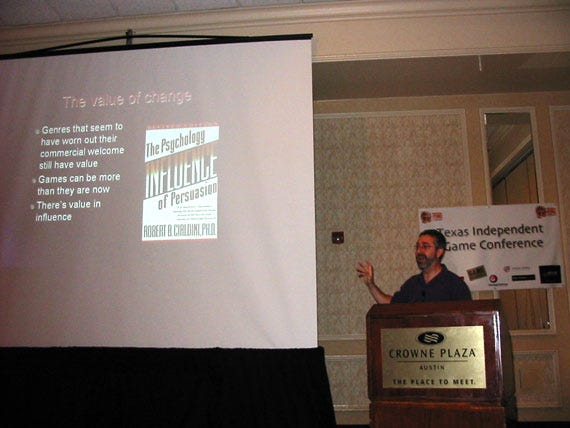

For most of the Texas Independent Game Conference, which convened for the first time last weekend in Austin, the tone was relaxed and friendly, even when speakers such as keynotes Greg Costikyan and Warren Spector elevated the mission of independent game developers to a battle for the medium's continued survival, offering their best words of encouragement while warning that success is not guaranteed. Commercial success, Spector said, can't be a driving force for “indies” -- rather, the drive should come from the desire to change the world. “You have to believe games can be more than they are now,” he said.

Warren Spector referenced occultist Aleister Crowley, suggesting that greatness is a form of deviltry.

About 140 people attended the two-day convention, according to conference director Steve Farrer. The conference came together after Farrer, who previously helped direct the Austin Game Conference, was approached by many independent developers expressing interest in coming together on their own terms, for a conference all their own.

The conference shared much with other game cons, with many trades of chatter, business cards and resumes and a range of vocations from students to seasoned veterans. Though most of the attendees were from Austin with a few more from elsewhere in Texas, some came from as far away as both coasts.

Liam Hislop, an instructor with Full Sail in Orlando, Florida, said many of his game development students saw going indie as a way to make the kind of games they want to make, outside of the big-publisher system. “We really need to see some kind of collective experience or collective knowledge somehow,” Hislop said.

Game industry veteran Joe Ybarra, now of Cheyenne Mountain Entertainment, flew to Austin from Mesa, Arizona, in part to recruit talent and teams ready to take outsourced contract work. He said he was impressed with how savvy those in attendance were. “I think the caliber of even the newbies is higher than it's been.”

Timothy Fuller of Playtechtonics shows off Starport, a 2-D MMO akin to Asteroids.

There was much to learn. “Blue Ocean Strategy” was the most-often plugged book, extolling the virtue of the untraveled path. Gordon Walton, now of Bioware's Austin studio, though his long industry tenure includes working as an independent as well as for big game publishers, gave his own talk advising indies to think carefully about what they want to do as much as who they are.

Working independently is a tradeoff with pros as well as cons, he warned, and indies must be passionate, dissatisfied and detached from the game market as it exists today, and perhaps most important, be at least a little crazy. Read all the books, absorb all the knowledge, but be brave enough to be irrational.

“Every game is an unreasonable proposition,” Walton declared. “Most people passed on great games.”

Walton inadvertently got a frustrated shriek out of Spector when he suggested that successfully selling investors on a game project, in a market where 80 percent of game projects don't make a return on their investment, is a confidence game. Apparently, given his reaction, Spector would rather such things not be spoken aloud.

Gordon Walton argues that being indie is as much about state of mind as amount of money.

In battle, it also helps to know what to fight for. Costikyan, in his keynote, argued that genres of games, ill-defined as they often are, could be seen as a measure of progress that stretches back to neolithic times. Games have progressed and changed so long as there were creators looking for something new, he argued, and each great leap forward in “shared mechanics” could be seen instinctively by players as a new genre.

Such leaps used to take hundreds of years in recorded history, back when cultures were isolated and rocks and sticks were the available game pieces, but have emerged with increasing frequency in post-modern times, and especially since the 1970s with the explosion of tabletop and board games, followed soon after by digital games.

That is, until just recently, Costikyan said. The creation of new genres seem to have hit a rut, one several years old (he cited Parappa the Rapper, the first “rhythm game” in 1996, as the last to occur “within” the game industry, but considered more recent novelties such as HeroClix and alternate reality games to have come from without.) Without continued innovation and the creation of new genres, he argued, the range of existing genres will gradually narrow, and what was once fertile ground will become sterile.

Greg Costikyan speaks rapidly. It was his birthday.

That won't change, he warned, in a system controlled largely by big publishers who think they know what's best for the industry. Rather, the only ones who can break the cycle are those working from outside the system – with the possible exception of Will Wright, whom Spector would later call “the Lord of the Rings of game development,” able to work within a huge system to create innovation.

No, indies don't have EA or Activision's deep pockets, Costikyan said, but neither do they have a big publisher's need for high return on investment. With less to lose, indies can even afford to fail and learn from the experience, he argued, potentially for the benefit of many. By daring to go where the giants of the industry dare not, he said, independent developers could be gaming's last, best hope for progress.

At this, many in the audience wanted to know about Manifesto Games, represented at the con by Costikyan, its CEO, and his partner, Dr. Johnny Wilson. Manifesto is meant to help bring indie-made games to market, primarily through a Web-based digital distribution system that Costikyan said would be ready soon, maybe even within two weeks. The trouble, he said, has been finding a system that works for all the different genres Manifesto plans to help sell – unlike the setup at Yahoo Games or Reflexive, variety will include installer size as well as user payment and trial systems.

This of course put Costikyan and Wilson in demand when it came time for the “demo party” at the end of the first night. Most with games on display were Austin locals such as Shannon Cusick of Orbis Games and Tom Kent of MinusOne, the latter showing a PC version of the cell phone game Jail Trail, produced through Austin-based Critical Mass Interactive.

Shannon Cusick, center, shows Orbis Games' Virtual Horse Ranch to Greg Costikyan and Dr. Johnny Wilson.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like