Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can you capture the fervor of your fanbase? With The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, Peter Jackson did so to great effect, and Gamasutra looks at how Bungie's Halo 3 and Sony's PlayStation Blog are harnessing the same power - to give people "relationships... with their entertainment idols."

The game industry has always been supported by enthusiastic communities of gamers. However, the relationship between development teams and the gaming public is often typified by either reticence or tension. For years, the communities and groups springing up around game releases have been left to their own devices. With the rise of the casual game market and wider acceptance of games, we take a look at what can be learnt from how films have capitalized on their enthusiasts and wider public following.

The success of The Lord of the Rings, and films like it, represents an against-the-odds production that drew heavily on support from an enthusiast community. Traditionally the film industry would keep its production process close to its chest, only making announcements when the majority of the work was in the can. Much like a magician's dark art, it was thought that to give too much away would diminish the audience's final experience.

However, this trilogy employed a strategy that involved fans in the project each step of the way. Peter Jackson and his team shared their progress in a frank and open manner with a wide audience through official and fan-run websites. Let's look at how Jackson publicly surveyed the task of starting filming:

"My team and I have poured our hearts into this project for the past three years, so it's a great thrill to begin actual photography. Filming three films at once has never been done before, in addition to which the project features state-of-the-art special effects, so it was essential to plan everything down to the last detail. We owe Professor Tolkien and his legion of fans worldwide our very best efforts to make these films with the integrity they deserve."

Jackson and his staff delivered blog-style entries dating back to the beginnings of their project that shared every aspect of the process from casting and location hunting to script writing and editing. Jackson himself took time during the busy filming schedule to record audio entries that answered questions from a variety of fan sites. One such site, TheOneRing.net, was particularly positive about the process: "Evidence suggests that the three films are being done slowly and with great care." Other sites such as RingBearer.com instantly took to Jackson's accessible and open approach, with an AintItCoolNews.com poster remarking, "I really have enjoyed this little experiment of Peter's, and I'm sure that most of you out there would agree we should do it again".

This transparency soon garnered respect and interest from both fans of the books and the wider public. Although it is hard to quantify, it is likely that this approach was at least partially responsible for the widespread success and fan-adoption of their film trilogy.

This transparency soon garnered respect and interest from both fans of the books and the wider public. Although it is hard to quantify, it is likely that this approach was at least partially responsible for the widespread success and fan-adoption of their film trilogy.

This is all very well for grand projects, but what about those with more modest budgets? Fledgling productions such as Joss Whedon's Firefly have also succeeded through fan support -- even with their studios cutting funding. A strong relationship between the Whedon and his audience was engendered by his willingness to listen to fan feedback and appear personally at events.

Websites, podcasts and interviews were all used to ensure they communicated openly and consistently with their fan following. Such was the support in the face of the series being cut, that Joss went on to produce a full feature length movie, Serenity. "This movie should not exist," commented Whedon, to his fans. "Failed TV shows don't get made into major motion pictures -- unless the creator, the cast, and the fans believe beyond reason. It is, in an unprecedented sense, your movie."

Whether through the big budgets and impressive plans of The Lord of the Rings, or through the fan love of Firefly, the film industry is now painfully aware of the need to enable audiences to have a sense of ownership of the entertainment they buy. There is no better way to establish buyer loyalty, or in fact to deliver a compelling experience, than to share the film's development and production process with the consumer.

Whilst games development is not identical to film production, it does share much of the same enthusiastic public response. Consequently games can appropriate some of the communication and community-building techniques employed by their celluloid older sibling. Games too can gain popularity and consumer ownership by opening their previously closed development processes to increased public involvement.

Halo 3 is an interesting project in this respect, as it is of similar importance and scope to The Lord of the Rings. As one of the most expensive game productions, it had plenty riding on its success for both platform-holder and developer. But how transparent was Bungie about the production of its game?

The developers have always provided updates, artwork and screenshots on Bungie.net. But this information often had a corporate and muted tone to it. They have excelled at providing ways for gamers to interact with each other through forums and strong post-game analysis functionality. However, they have historically made less effort and been less successful at providing access to the internal workings of Bungie and its production process.

Of course, that changed. In a move that is becoming more familiar in the games industry, Bungie has offered greater involvement to key individuals and groups in their enthusiast community. This ranges from adopting popular custom game types into the game's matchmaking, to the recruiting of respected voices from the community itself.

In this light, the move of Luke Smith from editorial site 1UP to Bungie is most interesting. Smith, a leading fan voice for Halo, was also well-known for his robust, direct approach to games journalism. His Content Editor role at Bungie means he is in a position to increase the studio's transparency to their enthusiastic players. He has been part of a greater focus on building, supporting and learning from the Halo 3 community.

Bungie now has a main tab of its website devoted to community; furthermore, this space makes clear how important this is for Bungie. The site describes the community area as somewhere you can go for "the latest news" and to tap into "the broader family of Bungie fan community sites all across the internet". Furthermore, Bungie has even adopted the fan group The 7th Column as its official Halo fan club.

That's not to say that the transition hasn't resulted in the odd teething problem. Sometimes, the transparency one might expect just isn't there -- Bungie has played the field with guarded, even marketing-esque, announcements. When credible rumors broke that the game might not feature a co-op mode, it could have been an almighty setup for an announcement of their four player online mode. It took almost two weeks before the announcement was ready, and Smith had to admit it was "time for us to sack up and tell you what's what regarding online co-op".

Although the main evidence is anecdotal, it seems clear that features such as Forge (which enables fans to collaboratively create and share custom games) are an acknowledgement of the importance of these communities for Bungie. The folks populating Bungie's various communities certainly recognize the shift in power that these tools represent. Any number of comments on the forums could be cited with essentially the same sentiment that we found in user ChaOtic's post on the official Bungie.net forums: "So excited for forge. Its gonna be awesome. Thanks for the heads up luke."

Bungie has become most successful at providing unprecedented access to the people and process that combine to create its games via the Bungie Studios Podcast. Since Smith brought his experience in podcasting from 1UP, this has become more regular and substantial in its opening of the studio doors to the public. Mission Designers, Sound Engineers, Test Managers and AI Programmers have helped paint a picture of what it is like to work at Bungie. As Smith recently commented during a visit back to the EGM Live podcast, "with the [Bungie] podcast we are focusing on getting our listeners and fans familiar with a bunch of the different faces at Bungie studios".

The Bungie podcast is a tangible step toward giving their hard-core customers a real insight into how games development works. When we asked John Davison, former Editorial Director of Ziff Davis, which publishes 1UP and EGM, he said, "it's the kind of relationship that previous generations couldn't have dreamed of having with their entertainment idols".

This really is the case -- fans are treated to a highly detailed account of each activity, even down to the bugtracking tools they use to manage their process. But perhaps more importantly than this, it manages to communicate the day-to-day experience of working in the environment to the fanbase, warts and all.

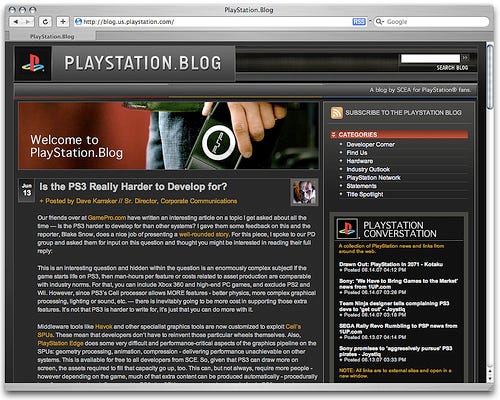

Although a very different animal, Sony's PlayStation.Blog also seems to be drawing on an increasingly open and transparent approach to communication with the company's hardcore following. Its previous communication had largely been closed and corporate in tone -- even, at times, insulting to consumers, truth told. The blog provides an open and direct space that enables Sony to appear less arrogant and more in-touch with the consumer's experience, something that has been welcomed across the board.

In a style that is more reminiscent of an indie developer than that of a major corporation, the blog provides space for wide swath of Sony's employees to talk informally about the projects they are working on. Along with up-to-the-minute news and information, these editorials provide a valuable window into the inner workings of the PlayStation world that has previously been out of the public glare.

The most significant aspect of the blog is not the content itself per se, but the style of communication. Posts are frank about failures and transparent about future plans to a degree that is most refreshing for a major platform holder. In just a few months, it has gone a long way to enable consumers to recover a sense of ownership of the Playstation project.

Lessons that are being learned are all well and good, but they don't get to the crux of the matter: identity. The largest difference between the two industries is the film and game industries is their relative maturity. Whereas film has been around for a good hundred years, games have rapidly evolved over a few decades. Films are clear about what it is that makes them valuable in the public square: story. Films provide narrative experiences of every shape and size.

Story is the centre around which that industry coalesces. When studios open up and provide greater access to their process, this determines what it is that they are communicating. The games industry doesn't yet have this clear view of itself. As Davison put it in a recent interview, "We're a scrappy collection of inter-dependent industries, and we've all come a very long way in a very short space of time, so it's inevitable that we all cling to what's worked for a long time. If we're going to get the message out to a wider audience, I think everyone needs to get comfortable letting go, and shaking things up a bit."

For the games industry, the opening up we are discussing is likely to be a painful process as it grapple with its identity. What is it that they do and who do they do it for? Davison, who is on the verge of launching What They Like, a site which will explain the appeal of popular games to parents, has a clear idea about the concepts which we should understand ourselves. "I think if we're going to successfully broaden the reach of all those interdependent industries, we need to go back to what the fundamental appeal of games is: play".

As the games industry takes innovative steps to communicate with and involve the wider public in their process, there is a lot that can be learnt from the films industry. It is clear that, just as with films, it is essential that it enables its audiences to feel a sense of ownership of the media they purchase. We can achieve this with transparent and honest communication -- be it a blog, podcast or video.

Whilst this will be successful at involving and motivating their hard-core enthusiasts, it won't really touch a wider audience until that audience gains a clearer sense of what is unique about a product. Rather than trying to adopt the techniques of the film business, developers will be better served by coming to terms with their industry's unique identity. Only when the industry has clearly identified its unique offerings, will it be able to speak eloquently about it in the public sphere.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like