Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

2016's ambitious forecasts for VR have come to a sudden collision with reality. Sales figures are far lower than expected. The Tech Adoption Lifecycle and the Hype Cycle suggest the future implications of these results.

Depending on the source you refer to, the state of Virtual Reality (VR)* is somewhere between exuberant growth to dismal underperformance, particularly now that 2016 sales results are available.

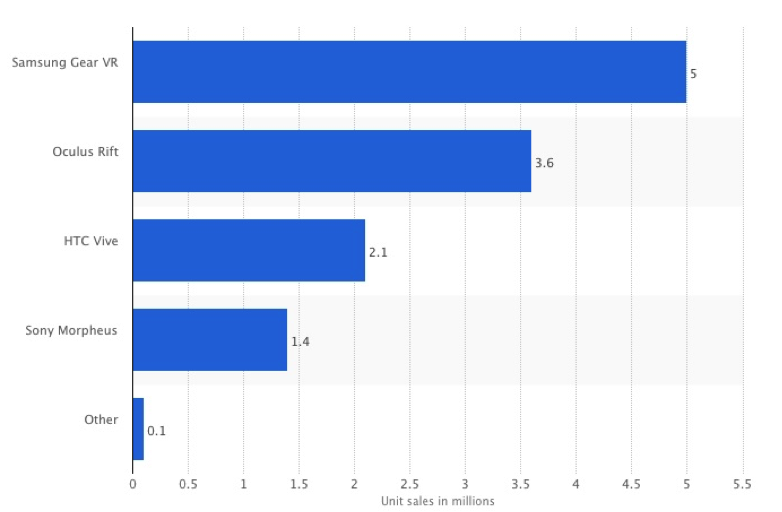

Early last year, industry projections proclaimed that VR was going to be the next big thing with sales numbers potentially as high as the eleven million unit range according to Statista. The newly-released sales reports have doused analyst enthusiasm with a large bucket of ice water. Is the situation really as underwhelming as certain observers are painting it, or are we seeing a need for expectation management within the tech industry; an industry which is prone to seeking the next big bang, rather than investing in a slow burn?

Projected virtual reality headsets unit sales worldwide in 2016 (in million), by device.

(Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/458037/virtual-reality-headsets-unit-sales-worldwide/)

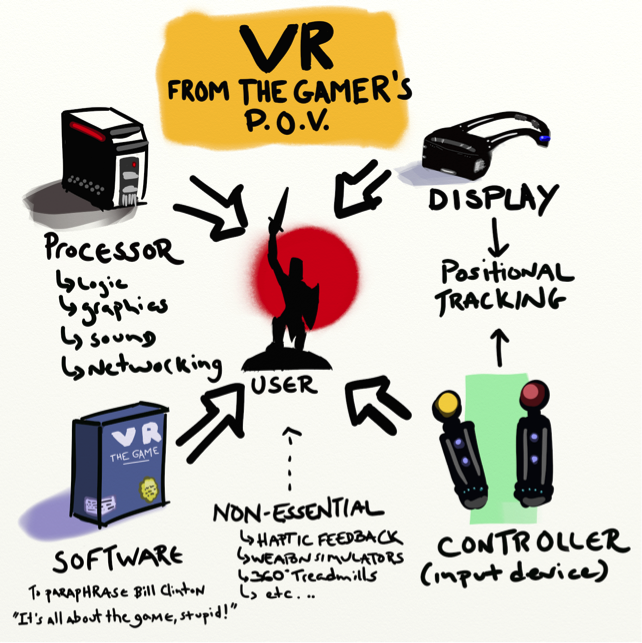

The advent of innovative headsets such as the Oculus Rift, Samsung VR, and HTC Vive, to name but a few, has led many to proclaim that VR is finally here. However, VR must be considered as a system, and strapping a screen to one’s face does not VR make. We cannot make viable predictions about the future course of VR until we have every aspect of that system in place.

Although a variety of descriptions of the components of VR equipment exist, I have found none that focus on the user experience. Therefore, we shall identify the following elements as VR as a system with respect to the user. It is comprised of four critical components: the processor (a computer or console), the display (in most cases, a headset), software (specific to the headset and the application within which the user will experience VR), and controller. Non-essential accessories can be added to the mix to achieve a number of effects, including enhanced immersion and haptic feedback.

Most importantly all of these components must be built with a single driving principle in mind: the user experience. Should one or more of the critical elements be lacking or offer an unsatisfactory experience to the user, the VR system as a whole will suffer. It is therefore essential to consider the success or failure of VR not on a component-by-component basis, but on a system level.

The gaming industry’s approach to VR has been the equivalent of trying to build an automobile by having multiple different part companies make parts and hope that a car emerges ready for sale. Without a single synchronizing principle or perhaps more effectively an integrator to bring every component together at the right time and place, it is to be expected that the current VR experience is sub-optimal. We are delivering the equivalent of a car without a steering wheel. Is it surprising that customers think that the experience is less than they were expecting?

Before proceeding, a short history of disruption is needed to set a proper context for the way ahead. The mouse, our trusty and all but indispensable input device for interaction with a modern computer, was displayed publicly for the first time in 1967. It wasn’t until 1983 that it began appearing on the consumer market with a hefty $299 price tag (http://www.macworld.com/article/1137400/input-devices/mouse40.html). It did not see widespread use until several years later. Not every computer user was convinced at first that it was going to be all that useful. After all, how could you justify spending so much money when your fingers could fly over your keyboard, flashing through directories on the command line prompt? And yet, it became the standard by which the vast majority of computer users interact with their computers.

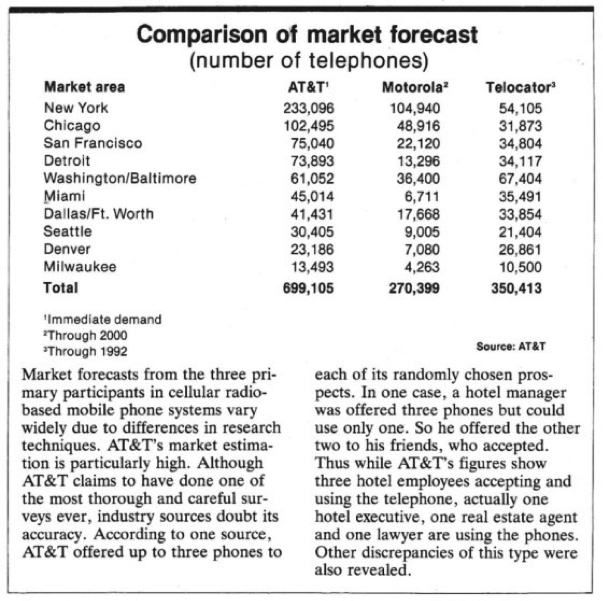

Casting our gaze to another example, let us consider the cell phone. Invented in 1973, and only finding its way to the consumer market in 1983, analysts in the 1980s only saw a small market for cell phones by the year 2000. After all, they were big, clunky, and the only businesspeople would ever need them. And yet, three decades later, cellular communications coupled to incredibly compact and powerful computing have changed the world.

Initial forecasts for cell phone sales vastly underestimated the extent to which they would become essential to our society by the year 2000. (Source: http://time.com/63718/shocker-in-1980-motorola-had-no-idea-where-the-phone-market-would-be-in-2000/)

In both of these cases, significant long term investment and ecosystem development were needed to for the technologies to meet their full potential. Had analysts forecasted larger sales, but the market could only support a smaller initial adoption of the technologies, downcast investors could have moved their money to other ventures, and neither of these two devices that we take for granted today would not have emerged from infancy.

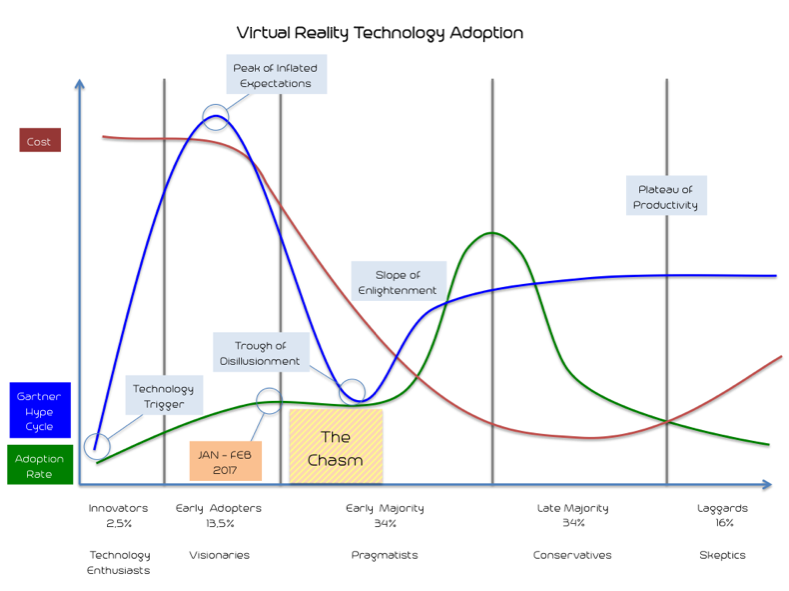

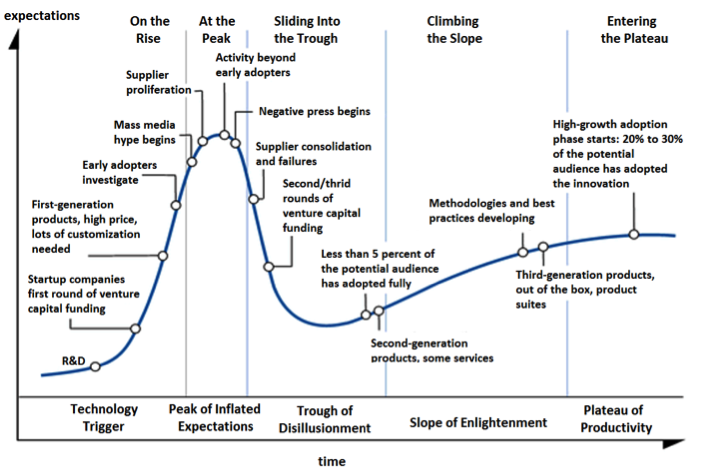

This brings us to a key concept for understanding VR’s future trajectory: the technology adoption lifecycle. The projected Technology Adoption Lifecycle for Virtual Reality (Green) with Economy of Scale (Red) and the Gartner Hype Cycle (Blue) overlaid.

The projected Technology Adoption Lifecycle for Virtual Reality (Green) with Economy of Scale (Red) and the Gartner Hype Cycle (Blue) overlaid.

The lifecycle is generally applicable to any disruptive technology, and is divided into five phases based on the market segment willing to adopt a given product. The first adopters are the innovators. The tinkerers, experimenters, and those that chase novelty for novelty’s sake. Although one could argue that VR as we know it began in 1960 with the Telesphere mask (https://www.vrs.org.uk/virtual-reality/history.html) and consumer-level adoption had already begun by 1995 with Nintendo’s Virtual Boy, they were little more than well-packaged 1st generation technology demonstrators. In terms of technological maturity, these could be considered to be approximately at Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 7, system prototype demonstration in a commercial environment (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technology_readiness_level).

Oculus Rift’s SDK 1 in mid-2013 (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oculus_Rift) represents consumer-level VR’s first ascension to the phase of innovator adoption. This is the first generation of fully-capable consumer level products. It has taken almost twenty years to finalize VR to a point that it can be considered TRL 9, an actual system employed in a consumer environment.

We are currently in the second phase, the early adopters. The various headsets have been on sale since 2015, and although we have witnessed what I consider to be a surprisingly strong uptake of VR in this time, it is nowhere near the wildly optimistic numbers that had been forecasted by market analysis firms such as IDC (http://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS41199616#) and Superdata Research.

One of the faulty assumptions behind these analyses is that consumers purchasing VR headsets will then stimulate the development of games, creating a self-reinforcing cycle to propel the adoption of VR. Though partly correct, this ignores the reality of VR as a system. Haltingly, we are seeing various developers creating creative and engaging controllers, software, and peripherals.

Once these essential steps are in place, consumers will begin seeing VR as a possible purchase. Therefore, the current sales figures should not be perceived as underperforming, but as an indication of the inherent potential that VR has to transform our lives. Even with essential components missing, 4.7M VR headsets sold in 2016. If we add Google Cardboard to the mix, we see that a staggering 93M potential users have experimented with VR in a single year. Even if a fraction of them convert every year, that would represent a healthy growth in such a novel gaming experience.

The current price point of VR is doubtless also holding back many potential consumers for reasons that have been well described elsewhere. As the technology matures, suppliers improve their production methods, and developers become more comfortable with the system’s inherent quirks and constraints, we will see economies of scale begin to drop the price of VR systems into a more consumer-friendly range. Although the major VR sets such as Sony, HTC, Samsung, and Oculus’s offerings, have only experienced modest sales, Google Cardboard’s immense numbers suggest that there is an eager audience ready to make the move once the conditions are favourable,

Once both the appearance of risk and the price point fall away, VR will traverse the chasm, that dark place where novel technologies that do not find an audience go to die. We now find ourselves at the edge of this precipice as developers, manufacturers, and investors warily eye VR’s 2016 performance. This is a critical juncture. Investors tend to focus on short-term gains and if they are discouraged by the near horizon prospects, they may divest at the very moment research and development is most required to transition towards early adoption.

VR’s potential, will ultimately be limited to the quality of experience it can provide as a system. In my previous life as a soldier, I have trained on a number of different synthetic training systems. I was also responsible for buying impressive blended reality technologies for firearms training. In these cases, as well as other commercial applications such as flight training, VR can get away to a certain extent with being clunky, expensive, and somewhat awkward. This is not so in the consumer electronics market. Customers expect sleek, streamlined, and aesthetically pleasurable experiences. The bar is also rapidly rising for military simulation.

Although defence, industrial, and training sectors could continue injecting Research & Development and procurement funds, as they have since VR’s early days, this will be insufficient to effectively transition the technology to the consumer sector. Although the defence sector was a notable driver of technological development until the 1990s, the consumer market now commands a far more potent capacity to accelerate innovation or relegate emerging technologies to the dustbins of history, as is evidenced by the rapid progression of cellular communications and smartphones since the advent of smartphones in the mid 2000s.

Once the chasm is successfully crossed, we will reach the early majority. Satisfied that their money will not be lost to a soon-to-be orphaned technology, and convinced that VR offers a tangible benefit to their quality of life, consumers will begin their adoption in earnest. Given the time needed for developers to create games, not technically impressive tech demoes, we are at least two if not three years away from when we will begin seeing the first members of the early majority trickling into stores and generating the financial momentum to propel VR systems to new levels.

In the meantime, developers and manufacturers have the opportunity to possibly squeeze in a new generation of hardware and software and improve economies of scale. Should we waver at this stage, and decide to reduce commitment to VR, then we shall inevitably not emerge from the chasm.

I will not cover the later stages of technological adoption in detail, as the chart speaks for itself. Once a majority of the market has accepted VR’s potential, sales will crawl along until even the laggards have bought into the idea. There will doubtless still be large numbers of people who will never embrace VR, just as there remain people who will never own a smartphone. However, as VR develops as a system and becomes ever intertwined with our lives, we will find that a healthy future lies ahead.

Interestingly, the media’s response to VR has closely followed the controversial Gartner Hype Cycle. This correlation increases the likelihood that the mapping above of the Technology Adoption and Economy of Scale are coherent with VR’s future progression if carefully nurtured.

Key elements of the Gartner Hype Cycle’s chronological progression map well with VR since Oculus’ Rift Kickstarter. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hype_cycle

Some evident concerns also surround VR’s current technical limitations such as limited field of view, resolution, appropriate alignment to the eye’s focal range, latency, form factor, etc. can also discourage gamers from entering the field. There are no current limitations that require novel physics to overcome. As such, miniaturization, continued ergonomic studies, improved algorithms, and the like will lead to ever increasing sophistication. If there ever is a doubt that such a progression is possible, look no further than the evolution of the cell phone. Originally bulky, clumsy, and single purpose, it has matured into something the creators could never have envisioned.

Remember this bad boy? (Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4a/Dkmb86g_487pr55s2hc_b.jpg)

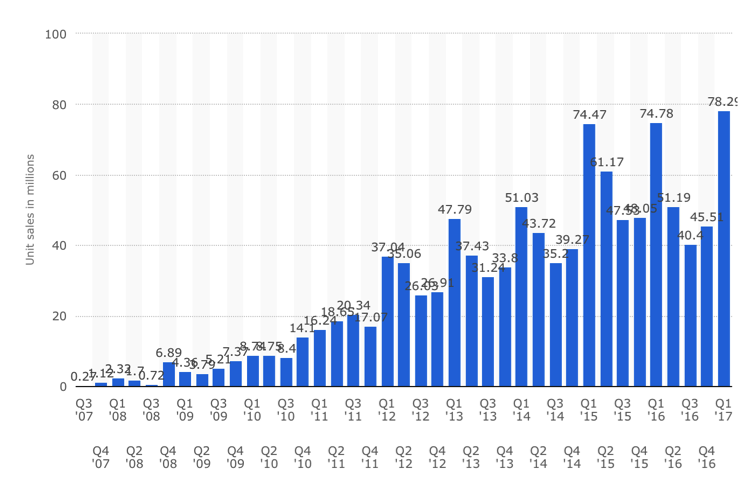

Speaking of cell phones, even the wildly successful iPhone, oft touted as a prime example of the market’s desire to rapidly embrace all things new, with its arrival primed by the development of the iPod, still comparatively crawled in its first two to three years of existence. (https://www.statista.com/statistics/263401/global-apple-iphone-sales-since-3rd-quarter-2007/).

Global Apple iPhone sales from 3rd quarter 2007 to 1st quarter 2017 (in millions of units). Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263401/global-apple-iphone-sales-since-3rd-quarter-2007/

And so we find ourselves at the edge of the chasm, looking across the gap wondering if we have what it takes to vault to the other side. I encourage all of you, investors, developers, manufacturers, and even eager consumers, to stay the course. Should we hesitate now, we will never know the wonders that await us on the other side of the precipice.

*Note: Although the focus of this essay is Virtual Reality, its conclusions can just as easily apply to Augmented and Blended Reality systems.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like