Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A detailed breakdown of everything it took to get this indie strategy RPG made; what sort of sales targets it needed to hit for me to make my goals as a developer; and what its sales actually turned out to be.

I’ve posted a lot about the development of Telepath Tactics: my design philosophy, my month-to-month progress, and so on. Now, a couple of months out from the game’s release, I want to take an in-depth look at Telepath Tactics from a financial standpoint.

Prior to Telepath Tactics’s release, I did not make games full-time. Rather, I had to maintain a day job in order to pay my bills (and to hedge against the possibility that Telepath Tactics might not be commercially successful).

I haven’t made a secret of the fact that I dislike having to compromise like this, nor have I hidden the fact that I very much want to go full-time with game development. Will Telepath Tactics tip the balance of my finances in favor of being able to quit my day job and develop games for a living? That depends entirely upon some cold, hard numbers, which we will now examine!

What did it cost to make?

I began developing the Telepath Tactics engine in April 2009, a little over 6 years ago. I worked on it only occasionally until March 2012, at which point I began regularly devoting 10-20 hours a week to the game on top of my regular full-time employment. For a four-month period during the summer of 2013, I took a sabbatical from my day job and worked on the game for 40 hours per week. Other than that sabbatical, I did not receive pay for any of the time I spent working on the game.

In total, I spent $13,266.25 out of my own pocket to pay for art, tools, and marketing opportunities for Telepath Tactics over the past three years. Of that, $6,034.38 was spent before (and during) its second Kickstarter campaign, all on expenditures to secure the assets and attention needed to crowdfund the game successfully.

The game’s first Kickstarter campaign did not succeed. The second Kickstarter campaign, however, raised $41,259.00, or 275% of its funding goal. After accounting for Amazon’s cut, Kickstarter’s cut, and pledges that didn’t go through, I eventually received $37,161.75. Of that, I was able to spend $29,560.78 on the game before the end of 2013, thereby dramatically reducing the taxes I would owe on the Kickstarter money come April 15, 2014. Still, I ended up owing several thousand dollars more in taxes for 2013 than I did the year before as a direct result of what I’d raised on Kickstarter; these taxes ultimately had to come out of the Kickstarter funds as well.

Counting my out-of-pocket expenses, the available Kickstarter budget, and all of the cuts taken out of the Kickstarter budget by the government and various private middlemen, Telepath Tactics’s monetary cost to develop totals $54,525.25.

Money isn’t everything, however. With all the recent brouhaha over developers underselling people on the cost of developing games, I feel obligated to mention that the true cost of developing Telepath Tactics is actually a good deal higher than that. Other than a small chunk I used to keep myself alive during the 4 months where I coded full-time, I did not pay myself for my work. The average entry-level salary for a full-time game programmer is something like $66,000 per year. The average calendar year has an average of 2,087 working hours for a full-time employee, making the corresponding hourly wage rate something like $31.62 an hour.

Starting around March 2012 and ending with the game’s release, I coded without compensation for 32 months at 10-20 hours per week (which we’ll average to 15 hours per week, times 4 weeks per month); prior to March 2012, I’d give a lowball estimate that I put in 400 hours or so getting the engine prepped. That’s 2,320 hours of work.

At $31.62 an hour, 2,320 hours of work puts an additional $73,358.40 of uncompensated labor onto the game’s true cost to develop. Had I compensated myself fairly for all the time I spent developing Telepath Tactics, the total cost of development would actually be something closer to $127,883.65.

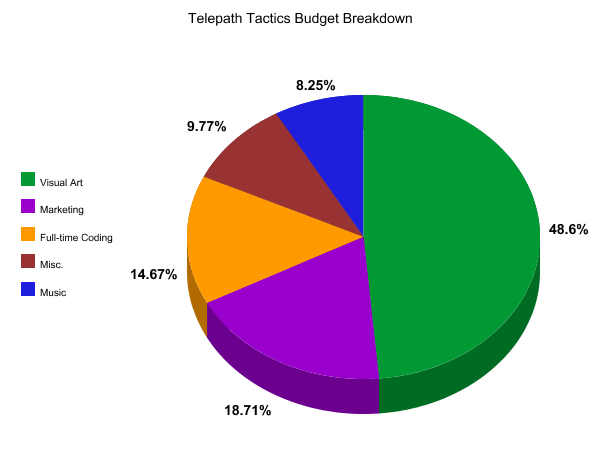

As far as money actually spent, the game’s budget breaks down like so:

$26,497.60 for visual art

$10,201.53 for marketing (mostly appearing at conventions)

$8,000.00 not starving or becoming homeless during my 4-month coding sabbatical

$5,326.12 for tools, Kickstarter reward fulfillment, and misc. business expenses

$4,500.00 for music

I was not even close to being able to pay for my own work on the game out of the game’s available budget. Thankfully, I went into development of Telepath Tactics assuming that I would be working without pay, and ultimately subsidized this cost by keeping a day job. This was what allowed me to make the game with the budget I had.

So what does that mean? Is that good?

Yes. RPGs in general are extremely costly to develop due to the high number of required assets and content compared to other game genres–this remains true of strategy RPGs as well.

Telepath Tactics’s budget is incredibly small given what we achieved with it. Compare Telepath Tactics to Fire Emblem: Awakening, for instance. Fire Emblem: Awakening costs $39.99 at full price; it reportedly needed to sell 250,000 copies at that price to be considered “worthwhile” (which we can assume means “profitable,” or something close to it). 250,000 copies sold at $39.99 equals just shy of $10 million. That’s about 200 times the budget that Telepath Tactics had (or 78 times its total cost to develop that includes my theoretical salary).

Hitoshi Yatagami of Nintendo has said that a WiiU Fire Emblem would need to shift 700,000 copies to cover the costs of development; WiiU games typically cost $49.99 or $59.99 new. Giving the benefit of the doubt and assuming the lower of these two prices, that means a WiiU Fire Emblem game would cost roughly $35 million to make. That’s about 700 times Telepath Tactics’s budget, or more than 273 times its total cost to develop.

But even without comparing Telepath Tactics to other sRPGs, it’s pretty impressive that it got made on the budget it had. This was a focused but ambitious game–and knowing the limited resources I had available, I tried to make every last dollar go as far as it could. Still, I was forced to procure a lot of assets:

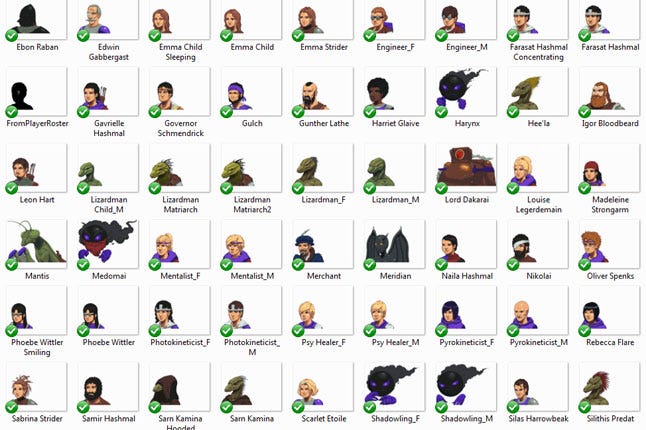

There are 23 base character classes in Telepath Tactics; 20 of the 23 base classes have both male and female sprite variations (male and female shadowlings look identical, and the bronze and stone golems do not have gender). Each of those 23 base classes has sprites for a promoted version of that class, with both male and female gender variations for 20 of them. There are also a handful of unique sprites for certain characters. All of the game’s character sprites are high resolution and smoothly animated frame-by-frame at 15 frames per second. There are a whopping 660 sprite sheets in the game, the vast majority of which animate in 4 directions, meaning that there are something like 2,400 high res, 15 fps character animations in Telepath Tactics. (I leave it to someone else to guess how many individual frames of animation that is.) Paying standard industry rates, this alone would have cost me more than the entire game’s actual, real-world budget.

There are 58 different visual effect animations that accompany the game’s attacks (including several big AOE effects with individual frames as large as 292 x 292).

There are 118 different character portraits and portrait variations in the game, each a pixel art graphic somewhere between 256 x 256 and 512 x 384 in size.

There are 6 tilesets containing approximately 1,800 pixel art tiles, each 64 x 64 pixels in size.

There are 210 destructible object graphics.

There are 91 different icons depicting the game’s various items.

There are 133 different images used to represent the game’s enormous roster of attacks and character abilities.

There are 5 large (940 x 580) pixel art cut scene backgrounds.

The game’s musical score consists of 26 original tracks. 22 of the game’s tracks were composed by Ryan Richko; the title theme composed by Nick Perrin; and I did the last 3 myself. The 23 tracks I didn’t write myself contain a whopping 57.5 minutes of high quality, original music.

And this is without getting into the title screen art or miscellaneous user interface graphics. Given the budget I had, this is an astonishing amount of graphical and musical content to have procured. My artists understood my budgetary position, and they graciously agreed to accept compensation far below what they truly deserved in exchange for making the game possible. Frankly, I feel bad that I wasn’t able to pay them more.

Despite my ruthless efficiency in getting as much out of the game’s budget as I could, I still had to make some hard choices on how to spend the budget I had. I dropped a variety of wish list items from the game, including: animated character portraits, idle animations, hurt animations, swimming animations, battlefield corpses for each class type, and custom character sprites for all unique characters. Faced with the choice of making the game deeper or making the game prettier, I sacrificed innumerable pieces of polish like this throughout development in favor of focusing on giving Telepath Tactics as much complexity and depth as possible. I don’t regret my decision, though I believe that this ultimately hurt the game’s commercial appeal.

How much does it need to make?

Now that we’ve established the game’s cost to make, and established that I was being extremely (perhaps overly) efficient in allocating its limited budget, let’s get into what sort of sales revenue I need to meet my goals.

My first goal is the same as every developer’s first goal: don’t actually lose money on making the game. To hit this goal, I only need to make back my out-of-pocket costs, or $13,266.25.

Thanks to the generosity of my Kickstarter backers, any sales I make beyond this “out-of-pocket expenses” level will give me money that can compensate me for my time spent (which I don’t care too much about) and can allow me to survive while making my next game (which I do care about). Since I’m not interested in taking back-pay for this game, we’ll operate under the assumption that 100% of excess funds will go toward funding my next game.

My second goal is to make enough money beyond the first goal that I can quit my day job and survive as a full-time indie developer for as long as it takes to put out my next game. This second goal is trickier to calculate, but still doable.

On average, the last two games I’ve made have taken me something like four or five years each to create. However, I made both of those games while holding down an unrelated full-time job. Development of my next game will occur much more quickly if I am able to work on it full-time. Let’s say that it will take me two years to create a new RPG while working full-time and reusing the existing Telepath Tactics engine and assets.

I am used to living on relatively low income, and can survive without any great privation on $24,000 per year. As established above, my time is actually much more valuable than this by any reasonable market standard, but we’ll use $24,000 per year as a baseline. Keep in mind that that’s not enough money for me to commission much in the way of new art or music, let alone visit conventions to promote the game–I’d probably need to run a Kickstarter campaign to get money for those things–but it will be enough to keep me not-starving, not-homeless, and with the necessary utilities (such as electricity and internet) while I work. Frankly, it helps a lot that I do not live in New York or San Francisco, and don’t have any children.

Two years at that income level is $48,000; however, self-employment taxes in the United States are more severe than the taxes one pays while working as someone else’s employee, so I actually need to earn more to remain at my baseline standard of living! Let’s inflate our two-year figure to $54,000 just to give me a safe buffer. For our purposes, then, $54,000 is the bare minimum in profit that I must make to hit my second goal.

To hit both goals, then–to both make up my out-of-pocket costs and then go on to make $54,000 in profit–the game must net me at least $67,266.25.

How many copies must the game sell?

Now that we know how much money the game needs to make, let’s figure out how many copies I have to sell to make it.

I’m selling Telepath Tactics at a $14.99 price point; in an ideal world, I’d be able to get really good sales numbers just from selling it direct to consumers. I use BMT Micro as a payment processor for direct sales. BMT Micro takes a 9.5% cut of each sale, which means that I make about $13.56 for each copy sold directly to players, before taxes. At that rate, I’ll make back my out-of-pocket expenses after 979 copies sold; to hit the second goal, I must then sell an additional 3,983 copies of the game directly. To make $67,266.25, I must sell a total of 4,961 direct copies.

This is unrealistic, however. In the current environment, most gamers buy games through distribution platforms, not directly from individual game developers. This means that I cannot expect to make the bulk of my money from direct sales. It is public knowledge that most online distribution platforms take something like a 30% cut of all sales. I am not at liberty to confirm that figure, but for our purposes here, let’s assume that it’s at least close to correct. This means that even without sales discounts, I receive a much smaller portion of each sale made through a distribution platform: specifically, about $10.49 for each copy sold at full price, before taxes (versus $13.56). Under those conditions, Telepath Tactics would have to sell 1,265 copies at full price (i.e. without any discounts) for me to recoup my out-of-pocket expenses via distribution platform sales. To hit my second goal, I would then need to sell an additional 5,148 full-price copies. To make $67,266.25 via online distribution platforms, I must therefore sell a total of 6,413 copies.

Even that isn’t realistic, however, as many of my sales were made during launch week (when the game was discounted by 10% on both Steam and GOG), and during the Steam Summer Sale (when it was temporarily discounted by 25%). Let’s make a rough guess and say that the game needs to sell 15% more copies to make up for revenue lost due to discounting–this bumps us up to 1,455 copies sold to make back out-of-pocket costs, and a final goal of 7,375 copies sold in order to go full-time as a developer. According to Steam Spy, this is well below the median for a game sold on Steam in any category, which is good news.

I’d like to end this part of our analysis with one final thought: it made a big damned difference to have (1) a successful Kickstarter and (2) an outside source of income during this whole process. Had I not run a successful Kickstarter, and had I found it necessary to pay myself the equivalent of a $66,000 annual salary for my work during the game’s development, I would have had to sell 14,020 full-priced Steam and GOG copies to make back my initial costs (versus 1,455), and 19,940 full-priced Steam and GOG copies to meet both goals (as opposed to 7,375).

Initial sales numbers

With that in mind, how is Telepath Tactics doing so far? Three months after release, I have sold approximately 3,000 copies total across all platforms, with gross sales revenue upwards of $36,660.

Net sales revenue, which accounts for the cut taken by the various distribution platforms, is a good deal lower than the gross–note that net is the amount I actually receive. Valve prohibits developers from disclosing data regarding sales made on Steam, so I cannot reveal my net revenue or otherwise break down my total sales by distribution channel. Ultimately, however, the breakdown doesn’t really matter for my purposes: regardless of what the distribution is, I (1) succeeded in fully recouping my out-of-pocket expenses, (2) made a small profit, and (3) failed to make enough money at launch to support myself making a game full-time over the next two years.

Is that good?

In a word: no. SteamSpy estimates that the average RPG on Steam alone has more than 10 times that number of owners. But more importantly, these sales numbers don’t meet my ultimate goal of allowing me to move into game development as a sustainable full-time job.

Someone unfamiliar with the games industry might think that $36,660 is pretty good for just the first three months of a game’s life span–and it would be, if I were a developer who was able to pump out games every 6 months, or even every year. But Telepath Tactics began development in 2009–$36,660 is not anything close to a sustainable amount of revenue for a game with such a lengthy development cycle.

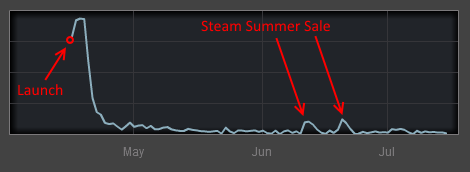

And unfortunately, the fact that it’s only been 3 months since release isn’t a reason to expect much more in the way of sales revenue. Games mostly behave like movies opening in theaters, with launch week analogous to a movie’s opening weekend: traditionally, the bulk of a game’s profits are made at (and shortly after) launch, with a mere drip-feed of sales following from that point onward.

True to form, sales of Telepath Tactics have thus far followed this “L” trajectory. The vast majority of all money made by the game was made in its first week, before the game dropped too far off of Steam and GOG’s respective “new releases” charts for prospective buyers to easily find it. Telepath Tactics is now in what is traditionally referred to as “the long tail”–the flat, horizontal part of the “L.”

There has been some reason to dispute the “long tail” model lately, as the emergence of bundles and major sales events over the past few years has managed to put some spikes into the long tail for digitally distributed video games. These events allow developers to wring out the proverbial towel and sometimes get significant sales spikes during otherwise fallow periods via a phenomenon that economists call “price discrimination.”

Following this theory, I participated in Steam’s summer sale. This gave the game an extremely modest bump in both sales and revenue during the first few days and last few days of the sale. Had Valve chosen Telepath Tactics to be a daily deal, the sales bump would likely have been much more significant; but they did not, and it was not.

Participating did not merely boost sales a bit–it also had negative effects. Selling Telepath Tactics at a significant discount attracted players who were less invested in the title, and several of them left negative reviews after playing the game for a short period of time. This hurt the game’s review rating, which pushed it further back in the charts, hurting its visibility–and thus, hurting full-price sales of the game going forward after the sale. Ultimately, participating in the Steam summer sale did not provide enough of a spike to make the difference between financial success and financial failure, and in the long term, it may even have been a net negative.

Conclusion

Telepath Tactics has received a bunch of critical praise from the print press for its clever mechanics and tight design–but from a commercial standpoint, it has not passed too terribly far beyond the minimal bar of “don’t actually lose money.” If it weren’t for the successful Kickstarter, Telepath Tactics would be tens of thousands of dollars in the red; and Kickstarter or no, if I’d needed to actually be paid for all those years I spent making the game, I would be left in a terrible financial position. (Thankfully, the game did have a successful Kickstarter, and I don’t care about back pay.)

I have some theories as to why it didn’t sell as well as I had hoped; I will explore those in a future post. For now, though, I’ve learned some valuable lessons that I’ll be taking forward with me into future projects. While Telepath Tactics didn’t meet my primary goal of permitting me to leave my day job and develop my next game full-time, it did do some very valuable things for me: it exposed my work to a much larger audience; it made me progress toward accumulating 1,000 true fans (or 10,000 modest fans, or some agreeable combination of the two); and it provided me with a robust engine and some great pixel art assets that I can use to quickly develop and release future titles.

That last part is important–if I can get to a point where, reusing the existing engine and assets, I can develop and release one new RPG per year, then sales comparable to Telepath Tactics’s sales would actually be quite sustainable for me.

However, I’m not there yet–I don’t yet have development down to a formula that would permit such a volume of quick releases. And aside from which, I’m simply not ready to surrender to creative stagnation: I have too many exciting ideas about new directions I want to strike out in with RPG and strategy game design. Indeed, I already have a couple of secret projects in the works with some of those ideas; my hope is that I will be able to make them more commercially successful than I was Telepath Tactics.

I’ll be announcing more as soon as I have enough to show. Until then, you can keep an ear to the ground on Twitter, on the forums, or even here on the Sinister Design site itself. Thanks for reading, folks!

This article originally appeared in two parts on SinisterDesign.net. You can learn more about Telepath Tactics here, on the game's official page.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like