Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra takes a close look at the business of republishing Japanese console and handheld games in the West, talking to executives from XSeed, Atlus, and GaijinWorks on building relationships, financials, and trends in the intriguing submarket.

Most of the mainstream publishers -- other than those Japan-based companies which release their own catalogues in the West -- may have lost interest in licensing Japanese console and handheld games for U.S. consumption. But this is not true for a growing number of small-scale publishers who are all vying for the same pool of products and seem to be immersed in a rough-and-tumble bidding war.

Winning, they say, depends not so much on who spends the most, but on whose connections and relationships are the tightest. And on whose localization skills are the most impressive.

The expanding competition for imports is due mainly to a challenging economy that puts a premium on games that can be had for a lot less than Western-developed games. Not only is there an abundance of unlicensed console/handheld games in Japan available for cherry-picking, but in many cases the games are already finished and their quality can be easily gauged.

"That's the main advantage of licensing Japanese games," says Ken Berry, director of publishing at LA-based XSeed Games. "Your costs are set from day one. Which differs greatly from going in and investing in the development of a game that could be delayed, or whose costs could spiral out of control."

"In most cases, when you license a Japanese game, you get to play the finished product before bidding for it. Smaller publishers are starting to see that as a great way to control costs."

On the other hand, Berry says, most mainstream publishers seem to be ignoring the plethora of Japanese titles because there's not enough in it for them. A huge licensed hit might sell 200,000 units at the top end, he says, but "a publisher like, say, Activision, is probably used to selling well into the millions on a domestic title. There's just no comparison."

XSeed is into its third year of licensing Japanese titles in North America, having opened its doors in November, 2004 but not having published its first product -- Wild Arms 4, for the PlayStation 2 -- until January, 2006.

While XSeed has evaluated a few European titles too, Berry says that his company, because it is still fairly small, needs to stay within its niche for a while, making full use of its competitive advantages.

These include the fact that all of its people are bilingual Japanese and that its president and founder, Jun Iwasaki, used to be president of Square Enix USA, the domestic subsidiary of Japan-based Square Enix. "His connections to the Japanese game sector are very extensive and we rely on them first and foremost," says Berry.

"Throwing a lot of money" at Japanese developers is not as successful a strategy as cultivating mutually beneficial relationships with them, explains Berry. "We aim for long-term, multi-title deals," he says, "which is why some developers bring us their games even before they show them to other publishers."

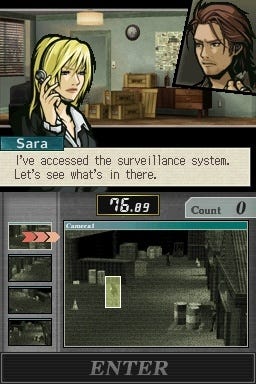

For instance, XSeed has been successful at building a relationship with Namco Bandai which began with licensing its Retro Game Challenge for the DS.

For instance, XSeed has been successful at building a relationship with Namco Bandai which began with licensing its Retro Game Challenge for the DS.

"We had to negotiate with them for months and months to finalize that deal," Berry recalls. "It was a title we really liked and we knew their U.S. office wasn't bringing it over. So our president put in some inquiries, found that it might be possible to license it, and we stuck with it for months until we finally did the deal."

"That definitely eased the process for the next deal, which was for Fragile for the Wii. That just shows you how important it is to build a relationship if you intend to license multiple games from a developer."

Also in its arsenal -- besides persistence -- is XSeed's own in-house localization team, which enables the company to specialize in story-driven role-playing games.

"Our bilingual staff has no problem playing through a 40-hour Japanese RPG, understanding what the characters are saying, and judging the quality of the game," says Berry. "They enable us to redo voiceovers, which otherwise would have been very time-extensive and costly work."

Last year, XSeed licensed six titles; this year it is doubling that to 10 or 12. The cost varies by title, by developer, and by the type of license but, in most cases, is based on the finished game, does not involve any development costs, and usually requires an upfront minimum guarantee followed by royalties per units sold.

Berry would not discuss typical licensing fees other than to say that "it depends on the game, on the development team, and how much time they had to develop the game."

Atlus U.S.A. is equally reluctant to discuss the bidding process and what it costs to license games, calling it "sensitive information we are unable to provide."

But Bill Alexander believes, too, that his company's strong connections with companies in Japan are vital to its success in evaluating and licensing games. Alexander is director of production of the 18-year-old Irvine, CA-based subsidiary of publisher Atlus Corp., Ltd. in Japan.

Similarly, he says, the company's strong localization skills have enabled it to specialize in RPGs. "While we've expanded the breadth of our offerings in recent years," he adds, "we know what our strengths are and we know what our most dedicated fans want."

For example, he says, their best-selling titles include flagship RPG series Shin Megami Tensei, Persona 3 FES and Persona 4. Upcoming is Demon's Souls, an action-RPG and Atlus' first game for the PlayStation 3. Early in 2010, Atlus will release Trauma Team for Wii.

The company has also entered the downloadable space with casual game Droplitz, and its new online division, Atlus Online, just launched Neo Steam: The Shattered Continent, the company's first MMORPG.

While, in previous years, fewer publishers had taken close looks at the titles coming out of small development teams in Japan, Alexander believes that is changing.

Bringing these games to the U.S. has always "required a great deal of effort to market and localize them for North America," he explains. "But with globalization continuing to bring cultures closer together... expectations from North American gamers are higher than ever before that quality products from overseas will make the trip over."

"So now, more publishers are exploring some of the terrific games released in Japan that would have previously never come to the States."

Victor Ireland is one of those publishers -- or at least he intends to be. After 17 years as president of Working Designs, a localization house for niche Japanese games, Ireland launched Redding, CA-based GaijinWorks in 2006.

Victor Ireland is one of those publishers -- or at least he intends to be. After 17 years as president of Working Designs, a localization house for niche Japanese games, Ireland launched Redding, CA-based GaijinWorks in 2006.

These last three years, the company has functioned as a "localization developer," most recently on Hudson's Miami Law, according to Ireland, who is the company's president. But he intends to begin publishing "eventually, perhaps in the next 18 months to two years," he says, focusing -- like XSeed and Atlus -- on RPGs.

These days the niche he intends to join is a much more crowded one than when he headed up his former company, "but there is still a huge amount of software in Japan that doesn't get licensed. So, yes, it's more competitive, but if you really know where to look, there's a wealth of titles available."

To be successful, Ireland explains, it takes the tenacity to play through the games to make sure you know what you're getting up front, it takes the ability to speak Japanese, and it takes a confidence in your ability to pick a good game. "If you have all three, the risk is low," he says.

In this sector, a publisher's function and responsibilities depend totally on the deal, he says. In addition to bringing the title to North America and localizing it, you may have to do some development work, particularly if you have access to the source code, Ireland explains.

"We like to do all the text and audio changes here," he says, "which provides a much faster turnaround time than if we have to send it back to Japan to update, which could take a week or two for each tweak. If we do it ourselves, it takes an afternoon. The result is a game with a much higher sheen because you've been able to try and incorporate and test many more options to get the game to play and look and feel great."

Ireland isn't as reluctant as his competitors when it comes to discussing the cost of licensing Japanese games.

"For an A or B+ title -- not an AAA title -- it can go anywhere from $100,000 to as high as $800,000 depending on the game," he reports. "That's the minimum guarantee. If the title is a hit, you could wind up paying an additional two to four million dollars in royalties."

"But if you're doing the developer's first game, if they are a small company, if they are hungry to license, then the cost could be less. And there are different kinds of deals -- revenue-sharing or upfront deals; there are a million ways to slice it. It really depends on your negotiating skills."

It also depends on how much the developer trusts the licensee and whether this is the first time they are working together or it is an old relationship. Or the relationship could be with another company that is close to the licensor.

"There are really too many small developers in Japan for you to be tight with all of them," says Ireland. "But if you know the right people, you can get the 'golden introduction,' which is almost the same thing. If you can get a good introduction from someone who has the trust of the developer you're pursuing, then 'bam' -- you're instantly up on the relationship meter."

"So we have relationships with well-established companies that are willing to introduce us to the licensors. In Japan that goes a long way, and is certainly better than cold-calling. If you think you can cold call, you're really fighting a tough battle."

It's a challenging sector to join, the pros agree. It takes experience, lots of connections, and at least a half-million dollars or more just to get your feet wet, says Ireland.

It's a challenging sector to join, the pros agree. It takes experience, lots of connections, and at least a half-million dollars or more just to get your feet wet, says Ireland.

"You need a lot of money to throw around, at least for the initial project," agrees XSeed's Berry. "But if you don't perform to a level where the licensor is satisfied, after the first project it might not matter how much you bid for the second project."

"What satisfies the developers is good communication and constant teamwork -- not just on localizing the title but also on how it's marketed. You have to run everything by them, get all the approvals down, and generally just try to keep them happy."

Which could all be a moot point if the industry's shift to digital distribution accelerates. According to Berry, he foresees the Japanese developers trying to publish online in North America without help from Western publishers.

"That's going to make it much more difficult for people like us who specialize in bringing the product to the retailers and marketing it," he says.

"That's where our relationships will come into play. Hopefully we've been able to show that we add value by having a lot of insight into the U.S. market. If the Japanese see that as a valuable service, we'll be okay. If not, well, we have a real high hurdle ahead of us."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like