Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the second part of our series on crowdfunding, we compare and contrast the different funding options available to game developers, so you can choose the one that fits best for you -- including a useful chart, and quotes from many of them.

[Following both an initial article which included the views of developers who tried crowdsourcing projects and an article in the May 2011 issue of Game Developer magazine, this latest look into the crowdsourcing revolution compares and contrasts the options available to game developers.]

In March of 2009, Josh Freese (a session drummer who's played with every band you've ever heard of) combined preorder-funding, tiered pricing, and a huge dollop of punk rock ridiculousness to fund his second album, Since 1972. For $7, you could download the album. For $50, you would get a signed CD, a T-shirt, and a personal thank-you phone call from Freese.

For $1,000, Freese would wash your car, take you out drinking, and then you'd give each other haircuts in the parking lot of the Long Beach courthouse. For $20,000, Freese, Tool's Maynard James Keenan, and Devo's Mark Mothersbaugh would take you mini-golfing, and then drop you off on the side of the freeway.

The publicity stunt was a huge success, getting write-ups everywhere from Wired to NPR, and "crowdfunding" took off. This was a huge boon to Kickstarter, a crowdfunding service that launched a month after the release of Since 1972, and quickly established itself as the market leader.

Crowdfunding services – websites that act as both a social network to connect projects with backers and as a marketplace or escrow house for project funding – have become a popular business model in the last two years, and several more have sprung up alongside Kickstarter, each with their own perks, quirks, and twists on the basic model.

Crowdfunding is a natural fit for an independent game developer who needs to connect with an audience and secure funding at the same time; rather than having to "prove" your game to a publisher, you're "proving" it directly to your customers, and you don't have to go out on a limb funding it yourself with no idea of whether or not you'll sell enough copies to recoup your investment.

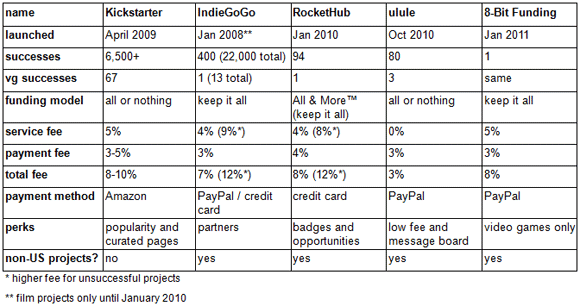

While Kickstarter is the most well-known crowdfunding service, it may not be the best fit for every video game project, so we're taking a look at five different crowdfunding services for video game projects to help you decide what will work best for your needs.

Kickstarter, the leader of the pack, has successfully funded over 6,500 projects since launching in April of 2009, 67 of which have been video games. IndieGoGo actually launched over a year before Kickstarter, but limited its funding to film projects until 2010.

RocketHub and ulule are two young up-and-comers who launched last year and are taking the basic crowdfunding model in interesting new directions; RocketHub is building gamification and an incubator of sorts on top of the basic model, while ulule is coupling its crowdfunding service with a message board and keeping costs to a bare minimum to create a very friendly and inviting space. Finally, 8-Bit Funding is the underdog of the bunch, launched at the beginning of this year as a crowdfunding service exclusively for video games.

The biggest core difference that separates these crowdfunding services is the funding model. Kickstarter and ulule both use an "all or nothing" funding model, meaning that no money exchanges hands until a project's deadline is reached, and only if the project has also reached or exceeded its funding goal.

IndieGoGo and 8-bit Funding both use a "keep it all" model where funding is paid immediately to the project, regardless of whether or not the project reaches its funding goal by the deadline.

RocketHub has a model it calls "All & More", which is a "keep it all" model that further rewards creators who reach their funding goals with tickets to its incubator-like "Launchpad Opportunities" service. (Both IndieGoGo and RocketHub also release half of their service fee to projects that successfully meet their funding goals as an added incentive.)

So, although only 400 IndieGoGo projects have successfully reached their funding goals, over 22,000 IndieGoGo projects have at least gotten some funding through the service. Likewise, RocketHub counts 94 projects that have reached their funding goals, but has distributed "over half a million dollars" among all of its projects.

Brian Meece, CEO of RocketHub, points out that a "keep it all" method means that "a creative can aim high with the confidence of a supportive safety net." Creators can rest assured that every dollar their project has raised is money in the bank, and don't have to worry about losing everything if they're just a few dollars short when the deadline strikes.

On the other hand, Kickstarter co-founder Yancey Strickler argues, "The importance of 'all or nothing' is that it protects both the creator and the backer. As the creator you know you're only obligated to follow through if you receive the funds that you said you needed, so you're not left having to fulfill obligations when you raised only $40 of the $40,000 you were trying to raise.

"And for backers there's 'safety in numbers'; you're only supporting something that's fully funded and you don't have to worry about 'where is this money actually going to go?' the way you might if there wasn't that sort of threshold that has to be reached."

Cédric Bégoc, community manager for ulule, agrees. "What happens if you don't reach the goal? You don't have enough money for the making of your project. What happens if we give you the money anyway? You end up making a sloppy project, because you don't have the means to fulfill your ambition. You are disappointed. And you disappoint your supporters and your fans.

"But, yeah, the crowdfunding site has taken its commission during the process. On the contrary, we believe the good way to use crowdfunding is the clear one: you need a budget, you succeed. At the minimum you get the budget, then you make the best of it, and no one is fooled."

Adherents of both funding models encourage creators to reapply if they don't reach their goals; an "all or nothing" project that doesn't reach funding can often succeed by reorganizing as a smaller project with a lower funding goal (as in the case of the "You Meet The Nicest People Making Video Games" project on Kickstarter), and "keep it all" projects can re-apply for their same goal minus the money they made previously, often reaching their final goal after several "rounds" of funding.

Deciding what funding model to use for your video game project is primarily a matter of how flexible your budget is; if you need a specific amount of money for a particular engine or assets, and you're willing to wait a month or two for the funding deadline, you're going to want an "all or nothing" model. On the other hand, if your project's expenses are already covered and you're committed to finishing the game regardless of how much funding you receive, then you'll probably want a "keep it all" model where your fans can cheer you on (and help you pay rent) with their preorders.

Many of these services have added their own unique features to help them stand out from the crowd. RocketHub awards users badges for doing specific things on the site like launching a project, backing a project, backing a successful project, etc. which Meece says has been a big hit with its users. RocketHub is also distinguishing itself from other crowdfunding services with a feature it calls "LaunchPad Opportunities".

Says Meece, "Think of RocketHub as an incubator for creatives with crowdfunding being the first step. We are in the process of lining up LaunchPad Opportunity providers for the next year -- and yes, some will include video game-oriented opportunities."

IndieGogo has partnered with a number of different companies to offer special services to its projects. Partners of particular interest to video game projects are Fractured Atlas, a nonprofit organization that makes contributions to projects tax-deductible, and MTV Networks, which keeps an eye on IndieGoGo for video, music, and video game projects to promote and acquire.

Kickstarter has recently added a new feature called "Curated Pages", where organizations like the IGDA and Kickstarter alum Kill Screen Magazine help prospective backers navigate Kickstarter's huge list of active projects by highlighting ones they're interested in.

Strickler says, "By and large it's about the endorsement of someone saying 'this is cool', and whatever a backer chooses to take from that is up to them.

"This is a feature that's going to grow, and you get a better sense of it when you look at how someone like RISD [the Rhode Island School of Design] is using it to highlight projects by their students and alumni and collect it in a central place, so that if you're part of the RISD community, you know where your first stop is going to be.

"So I think the pages will develop like that, not only in games in particular but even in specific genres, and I think we'll see that in the next couple of months."

Strickler believes that Kickstarter's comprehensive nature is what makes it an especially good fit for video game projects. "Millions of people come to Kickstarter every month looking for cool things to back," he says, and even if they're usually interested primarily in film or music projects, they could be enticed by an exciting video game project.

8-Bit Funding's Geoff Gibson feels the opposite is true, and says that crowdfunding for video game projects should be segregated for "the same reason why we get most of our video game news from sites like IGN or Joystiq instead of the New York Times."

8-Bit Funding's Geoff Gibson feels the opposite is true, and says that crowdfunding for video game projects should be segregated for "the same reason why we get most of our video game news from sites like IGN or Joystiq instead of the New York Times."

Gibson feels that video game projects get overshadowed by the more mainstream appeal of film, music, and design projects on most crowdfunding sites, and the low number of video game project successes across all of these crowdfunding services seem to support his conclusion.

Bégoc says that "projects come by type" on ulule. "We have a lot of short movie projects because, at some point, we received two great movie projects. They were both successful and attracted a lot of attention from the short movie community." Now that ulule has launched a few video game projects, he expects to see a similar surge in video game project popularity on the service.

In closing, Strickler and Gibson both feel that connecting with your backers is the key to a successful crowdfunding project. "You want to have a video that not only shows the gameplay footage but also preferably shows the creator as well; I think people like to know who it is that made something," says Strickler.

"You also want to have rewards that are fairly-priced and that will allow everyone to benefit from the success of the project, because with every project it's important that not just the creator benefit, but that everyone share in the success. I think that inspires a lot of people to get involved and also keeps them coming back."

Gibson adds, "Any developers out there thinking that they can make a project on any of the crowdfunding sites and watch the money roll needs to reconsider creating a funding project altogether. It takes a lot of work, a lot of constant marketing and asking and poking and prodding to get people to take notice and open up their wallets a little bit. If they don't do that their projects won't succeed."

You can visit the sites by clicking below:

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like