Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Game recruitment ads shout about passion -- but is passion as necessary as it's cracked up to be? Experienced developer Adams writes here about the difference between a passionate amateur and a hard-working professional, and why one is, in reality, more important than the other.

Read a few dozen game recruitment ads, and you'll soon notice that most of them say they're looking for people with a passion for games. It sounds very enthusiastic and romantic and fun. The ads go on and on about how much passion the employees at the company have, and how they're looking to employ people who are just like them! "Wow!" says the naïve young modder in his bedroom. "I have passion! That's for me!"

Industry recruitment ads say this because they're hoping to attract starry-eyed innocents who just love games. Many game companies depend for their survival on the exploitation of starry-eyed innocents. Ideally, of course, they would like to find highly-experienced starry-eyed innocents, but there ain't no such animal -- you can be innocent or you can be experienced, but not both, as William Blake observed.

"Passion" is an excuse used by employers to mistreat their employees. Your passion is supposed to make up for the insane hours and low pay for which the industry is notorious. Many job ads emphasize the importance of passion in applicants; few emphasize the quality of life that the employer offers.

How many of them talk about their on-site child care, their whole-family insurance plans, or their generous vacation policies? None. They're all assuming the reader is a young single male with no interest in family life, and ideally, no interest in taking any vacation.

This practice does a disservice both to the innocents and, if they would only realize it, to the human resources people who have to sort through the job applications. It encourages everyone who has a passion for video games, regardless of their skills as a developer, to apply. This means that large numbers of people get unrealistic hopes and send in resumes for jobs they're not qualified for, and the HR people have to dig through them all.

Let's talk about what passion is good for, and what it isn't. Passion is a burning, ungoverned desire or other emotion, such as anger. In its extreme form, it's really obsession, and that's never good. When cultivated intentionally, passion is a form of self-indulgence. It feels nice, but by itself, it isn't necessarily creative or reliably productive, and it has nothing to do with talent.

Art requires passion. True art comes from the soul, and the artist must believe passionately in what she does. Someone who makes passionless art is a hack. Art also requires passion because art is even more badly compensated than the game industry is.

Art requires passion. True art comes from the soul, and the artist must believe passionately in what she does. Someone who makes passionless art is a hack. Art also requires passion because art is even more badly compensated than the game industry is.

The game industry doesn't produce works of art for the most part, and for every visionary who insists on following her own dream regardless of where it leads, the industry needs about 200 worker bees who actually make the products that sell.

Peter Molyneux gets a lot of credit for being an industry visionary, but he's not the one who writes the code or models the landscapes. The vast majority of the people in the industry don't get a choice about what to work on.

The company says, "We need a new driving game for 2014, and you're going to do the wheels and mufflers." You can do it or get fired. There's a lot of grueling donkey-work in game development, especially at the lower levels.

There's another problem with passion, too. Because it's raw, unreasoning emotion, it doesn't necessarily play well with others. If my passion tells me to make the game one way, and my producer's passion tells her to make it another way, there are bound to be fireworks. Games aren't movies; we don't hand total creative authority to a single director and let his passion rule the project. Games are collaborative efforts, and that requires compromise and diplomacy.

So how do you keep up that burning enthusiasm when your job requires a lot of tedious, repetitive work, and a lot of compromises to your vision? The truth is, you don't have to. When passion fails, what gets you through the day is professionalism.

Professionalism is a combination of factors. One is desire to do a good job for your company -- if your employer treats you well, you want to give them your best.

Another is desire to do a good job for your customers, the players -- they are the ones who will use your products, enjoy them, pass judgment on them, and in the long run they are who really pays your salary. Still another -- and perhaps the most important -- is a desire to do a good job just for yourself, simply because you take pride in doing it.

Professionalism is about knowing your job, doing it well, and being proud of it even if you wouldn't buy the resulting product. As the markets for games expand, fewer and fewer of our customers will have the same demographics, and interests, as game developers.

Few of us are old ladies, and fewer still are little girls, but a good many of our customers are, and we owe it to them to do just as good a job for them as we do for Gears of War fans.

Recently I consulted on an important serious game in development in the Netherlands. It's intended to train surgeons in a way that's much more entertaining than the usual surgery simulators; it will keep them engaged for longer and improve their hand-eye coordination. We're working to make it accessible to the general public, too. I'm not really the intended audience, but that doesn't matter; the developers have hired me to give it my best and that's what I'm doing.

I hear a lot of people say, "I wouldn't want to work on any project I didn't feel passionate about." That's lovely as a statement of artistic integrity, but as projects get bigger and bigger, fewer and fewer developers have the benefit of that luxury. Instead, you do it out of professionalism.

I worked for years on sports products. They were not, and still are not, my favorite genre. I took the job because it was a big improvement over my old job, for a good company, on a well-regarded team. I found a niche where I could put my talents to good use, and I significantly improved the quality of our products in my particular area of design, which was simulated play-by-play commentary.

Was I passionate about it? No. I was professional about it: I did a good job for the company. What's more, I came to appreciate the unique challenges of sports game design, and I was delighted that our fans thought our game was the best on the market.

I would much rather hire someone with professionalism than passion. Professionalism is dedication to doing a great job even if you're not the target audience.

Somebody who will turn in good work on any project I put them on is much more useful to me than someone who is really enthusiastic about one genre and moans when he's asked to work on anything else. I'll make an effort to move the former to something she likes when I can. The latter gets fired at the end of the project.

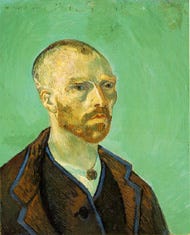

They're not mutually exclusive qualities, of course. One of the best examples of passion combined with professionalism was Vincent Van Gogh. There's a lot of shallow psychoanalyzing about Van Gogh -- "his paintings are so distinctive because he was mad," and so forth.

But Van Gogh was no naïve artist operating on raw talent and passion alone. If you read his letters, you discover that he was a well-educated scholar of art, much influenced by the ideas of others.

His passion kept him going when nobody would buy his works, but it was his professionalism -- his endless desire to learn more and do better, that exploited his talent to its fullest. Van Gogh's early works didn't amount to much. It was his growth as a serious, thoughtful, professional artist that turned him into what he became.

His passion kept him going when nobody would buy his works, but it was his professionalism -- his endless desire to learn more and do better, that exploited his talent to its fullest. Van Gogh's early works didn't amount to much. It was his growth as a serious, thoughtful, professional artist that turned him into what he became.

In fact, his bouts of madness had nothing to do with it; they disturbed his thinking and prevented him from painting. If anything, his work is all the more impressive because he was able to do it in spite of, not because of, his illness.

It's time for a moratorium on recruitment ads that demand passion. It sounds cool, but ultimately, it's meaningless except as an excuse for demanding long hours and offering poor benefits. By itself, it's not much use to development companies, either.

Passion is no guarantee of talent or even basic competence. Ability, pride, discipline, integrity, dedication, organization, communication, and social skills are much more useful to an employer than passion is. And they're more useful to you, too.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like