Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Market forces seem to be leading us to a crash for lower-end developers. Here's a (probably crazy) proposal to fix it.

I've been thinking a lot lately about the financial future of developers.

To go back a ways, back in 2006 I suggested that you could look at the winding path a piece of media takes to the public in this way:

A funder of some sort ponies up the money so that a creative can eat while they work. Sometimes this is self-funding, sometimes it's an advance, sometimes it's patronage. |

|---|

A creator actually makes the artwork. |

An editor serves the role of gatekeeper and quality check, deciding what makes it further up the ladder. They serve in a curatorial role not just for the sake of gatekeeping but also to keep the overall market from being impossible to navigate, and to maximize the revenue from a given work. |

A publisher disseminates the work to the market under their name. A lot of folks might think this role doesn't matter, but there are huge economies of scale in aggregating work; there's boring tax. legal, and business reasons to do it; it serves brand identity, making the work easier, to market... |

Marketing channels make it possible for the artwork to be seen by the public: reviews, trade magazines, ads. This is how the public finds out something even exists. |

Distributors actually convey the work to the store's hands. This role functions in the background, but it's absolutely critical. There's a lot of infrastructure required. |

Stores then retail the packaged form of the artwork to the end customer. Stores have their own branding task, and likely serve as a curatorial and recommendation engine all over again, this time trying to find the right fit for the customer. |

The audience then gets to experience the work. |

Re-users then take the creation and restart the process in alternate forms; adaptations to movies, audiobooks, classic game packages, what have you. |

At different times, and for different media, different people have held ownership of chunks of this pathway. For example, an indie today handles both their self-funding and their creation. There are popular writers, like James Patterson or Robert K. Tanenbaum, who actually outsource the creative part. EA's big business initiative that led them to dominating the game landscape for quite a while was that they decided to build their own distribution network to retail long before anyone else (there used to be independent videogame distribution companies that sat between publishers and retail).

All of these roles still exist, and likely they will always exist. It's just that as the landscape changes, some people start to wear multiple hats, fulfilling more than one role.

Let's take the Apple App Store as an example.

You likely fund yourself.

You like make the game yourself.

The App Store acts as editor, though they have a much lighter hand than traditional editors have had.

If you self-release, you're supposedly the publisher, but really, it's more like Apple is.

Apple also controls the most important marketing channel, which is Apple's own front page, charts, and features.

Apple is the distributor, as is the case with all App Stores.

Apple is the storefront.

The player is the player, hurray!

Alas, the re-user is often a cloner.

One consequence of the changes in the industry has been to consolidate more and more roles into the hands of fewer organizations. There are less publishers. Less distributors. Less marketing channels. Less stores. About the only thing there are more of is consoles, and that's because what we call "a console" isn't:

Playstation 4 & Vita

XBox One

WiiU

Nintendo 3DS

Ouya

Amazon Fire TV

iOS App Store

Google Play

Steam.

These are all functionally the same, as far as a game developer is concerned. Today, a console is really just a hardware front end to a digital publisher/distribution network/storefront. Call it a "metaconsole." Even with this proliferation of ecosystems, we have a net loss in diversity and complexity of the overall landscape.

Less, generally speaking, is bad. It means fewer outlets for a creative, and fewer choices for a consumer. It's great if you are one of the few. But in practice, market dynamics tend to clean up this sort of messy proliferation over time.

While the landscape is wild and crazy, creativity reigns. Wacky ideas get tried. Some of them hit. Genres are created.

So what happens when markets mature? Well, whoever had the largest piles of money tends to start swallowing up more roles. And they get entrenched, and they stay entrenched until there's a massive enough shift. In those mature markets, creators have to compete on money. Not creativity. Not innovation. Money. Money in the form of marketing spend, in the form of glossy production values, in the form of distribution reach.

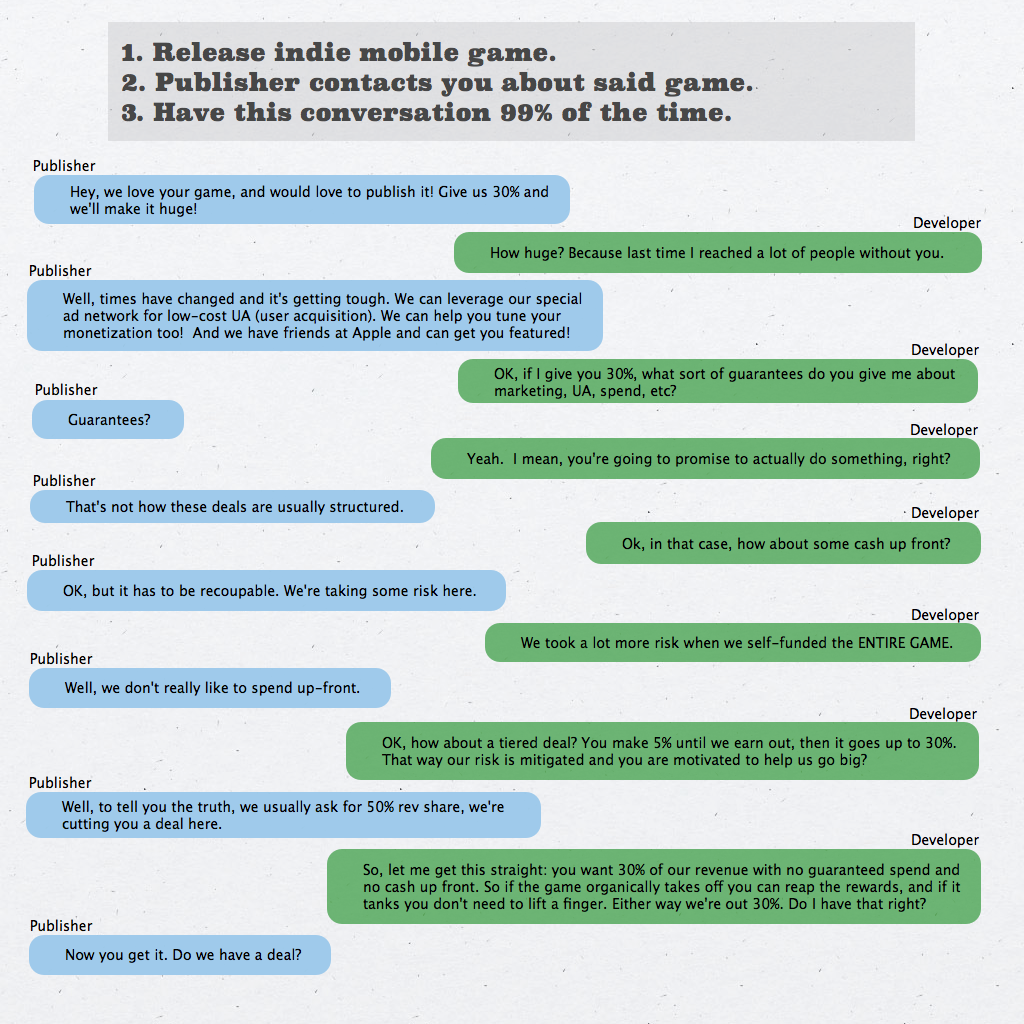

In a different talk back in 2011, I doomcast indies. Basically, these trends were plenty visible then, and I said that I was very worried about indies because as costs rose, they wouldn't be able to compete in terms of marketing dollars and glossiness. They might still make great games, but they would rapidly end up beholden to The Man again, as the need for deep pockets rose. It's a recipe for hollowing out the middle, you see. Midsized devs have to either become big ones, be subsumed by big ones, or slip down to become small ones, who probably don't make a living (but might get a stroke of luck and win the visibility lottery, as viral hits do). Those who have the money become more and more predatory, as in this parodic conversation between a dev and a mobile game publisher that was making the rounds yesterday.

In the long run, though, this is bad for the ecosystem owners. Right now, as it always is in mature markets, the conventional business wisdom is to move to a blockbuster mentality. Place few bets, spend like utter mad against them (500m for Destiny, is the current news item, but in the past we have seen the same story for GTA, SWTOR, WoW, Final Fantasy, and Sims Online. Even for Cityville). The risk, of course, is that by reducing the portfolio diversity to that degree, a few failed blockbusters in a row topple the whole organization. Any structure that depends solely on blockbusters is not long for this world, because there is a significant component of luck in what drives popularity, so every release is literally a gamble.

So a wise org is always trying to keep the fringe alive through good curation and hedging bets.

Unfortunately, in these self-publishing days, where all the risk has been offloaded as much as possible to the creator who self-funds, I think there are some new dynamics at play.

Some dev makes a game and puts it up on the store. Its mere existence provides real, tangible financial value to Apple -- after all, the ads for iPads are all about the apps, and even adding one more useless one to the 7000 that appear each day is putting another brick in a large edifice, giving Apple another number to trumpet.

But the median game uploaded to the App Store makes zero dollars.

It certainly doesn't cover its costs. If it was wildly profitable it probably became so with big financial backing because the market is more hit-driven. So the value goes to the company that owns the game, not down to the individual developer, except in rare cases like a Flappy Bird. And that rare case is what the vertically integrated "consoles" count on -- because it instills dreams and hopes that you, too, could make that happen. And you could, just like you could go to Vegas and win ten million bucks on a single quarter.

Basically, at the bottom end of the market you have devs who get to be creative but not eat. At the top end you get devs who get to eat but not be creative. And there is no middle.

In 2006, my prediction was today's world, and I offered up as solutions the following:

build direct relationships with your audience

celebritize yourself

create games that are services, to lock in that audience

develop alternate revenue streams, by creating games that are IPs that support downstream uses of the IP

Get someone else to fund, but make yourself the creator, the editor, the distributor, the re-user.

This is all perfectly good advice. Excellent, even, considering it was given in 2006. But here's the rub.

Some people aren't good at all these roles. And even if they are, the more they have to pay attention to the non-creative aspects, the more it is likely to affect their creativity. They start not pursuing a wild idea because they see no market for it. They start changing their game design to make the game be a service even though it's working against the grain of the game. And lastly, it means being a business entity, to a much larger degree -- which almost certainly means that someday you will lose control of it.

The fact is that the old solution does work. But it also returns us to the cycle, to a world where the massive indie explosion we saw doesn't exist.

And don't go thinking that "Oh, but Sony is good this generation!" or "Steam is on the developers' side!" The fact of the matter is that the role molds the organization. The more Steam becomes a metaconsole, the more it acts like one.

Couldn't we take a cue from music?

Some external organization should exist that provides credit validation. Today, practices like "oh, she left early, so we'll just list her in Special Thanks" and "he was Lead, but only for the first half, so we'll list him under Additional Programming" are not just rampant but culturally accepted practices. Fellow devs will argue that staying to finish a title is the most important thing, which is ludicrous.

Just run some thought experiments; if one person made a whole game for a year, except for the last five minutes, whereupon someone else took over, would you say that they should get credited as "additional"? OK, what if it's a week? A month? What if they were only there for the first month, which means "all" they did was "just" the game design, architecture, core engine, and art direction? At what point does their contribution become ancillary?

This organization then can maintain the accurate, comprehensive database of all game credits. This will be incredibly useful for other purposes (game resumes are routinely falsified, for example). Further, it can do things like recognize ports and sequels and the like, so that say, Dona Bailey still gets credited on every derivative of Centipede. But our main purpose is this:

All game outlets -- App Stores, social networks, what is today the plumbing of our lives -- contribute into this org's bank account, right off the top, out of their 30% cuts. Facebook alone made over a billion dollars in game revenue every quarter last year. Add in Google, Sony, Microsoft, Apple... they really don't need to skim much off the top to put into this org's coffers.

Why is it that these folks do it? Because they are also in the position to know what gets played.

And then this credits organization, acting much like a Performing Rights Organization, distributes almost all of that money back to everyone in their database.It's effectively royalties for every play. Dona Bailey would get a check for people who play some Centipede derivative today.

Oh, and you don't distribute this evenly. Not fairly, no: unfairly. Tilted so that those who earned the least get a disproportionate payment. After all, if you got lucky in the popularity lottery, you are already earning your capitalistic reward right now. No, this is more for when you are old and gray and haven't been at that company for ten years, but your game is still making them money.

Why this construct? Because game creators

work for hire

don't have moral rights in the US

don't have the sort of IP protection that other media do

Games are the worst protected creative job there is. And given the libertarian politics that are common currency in the industry, they are also the creative group least likely to organize.

How feasible is the above? I don't know. But I do know that if every developer who put a game up on the App Store knew that they weren't just going to lose their time and money on it or get screwed over by faceless moneygrubbing gladhanders, we'd see more diversity, more creativity, and plain old more apps.

And if that happened, the ecosystems could a) be a little less worried about solving a probably unsolvable discovery problem b) trumpet ever growing numbers c) likely grow their audiences as diverse creators lead to diverse customers d) hedge the blockbuster problem that is stalking them and will someday hunt them down and kill them.

Ah, I'm probably nuts. I'm sure my suggestion is buggy as hell. But it's the best I've got at the moment.

-----------------------

As you might guess, Greg Costikyan and I had some conversations during GDC.

(Crossposted from my blog at http://www.raphkoster.com/2014/05/07/the-financial-future-of-game-developers/)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like