Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest in a series of Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material originally to be included in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's new book Vintage Games, we examine Eugene Jarvis' devious but delightful 1980 arcade game Defender and its descendants.

[In the latest in a series of Gamasutra-exclusive bonus material originally to be included in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton's new book Vintage Games, we examine Eugene Jarvis' devious but delightful 1980 arcade game Defender and its descendants. Previously in this 'bonus material' series: Elite, Tony Hawk's Pro Skater, Pinball Construction Set, Pong, Rogue and Spacewar!.]

When Eugene Jarvis was developing the now-classic side-scrolling shoot-'em-up[1] arcade game Defender for top pinball machine manufacturer Williams Electronics, he admits that the company's management was skeptical.

Furthermore, Defender's response at the November 1980 Amusement & Music Operators Association (AMOA) trade show was indifferent at best. "They were afraid of this game," said Jarvis, reminiscing on the game's debut. "I guess it was all the buttons."[2]

Unlike most games of the era, which featured at most a few buttons and a controller, Defender offered five buttons along with a joystick to perform the game's esoteric actions.

Nevertheless, despite its extraordinary difficulty, which was arguably balanced by the depth of the gameplay and strong audio-visuals, Defender became a smash hit for Williams.

It quickly established both the company and Jarvis as players in the rapidly expanding arcade game industry. The relationship led to another hugely influential classic just two years later, Robotron: 2084,[3] which is detailed in another bonus chapter.

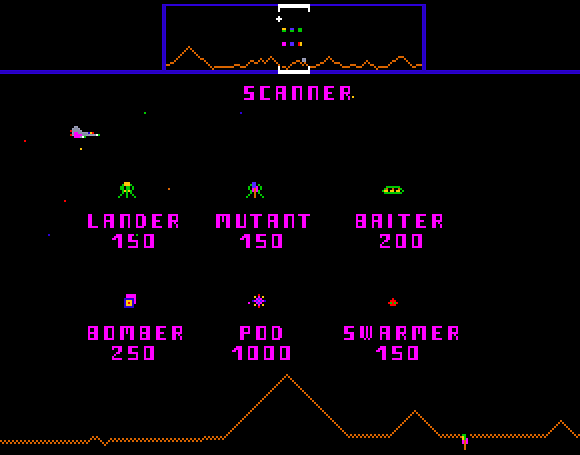

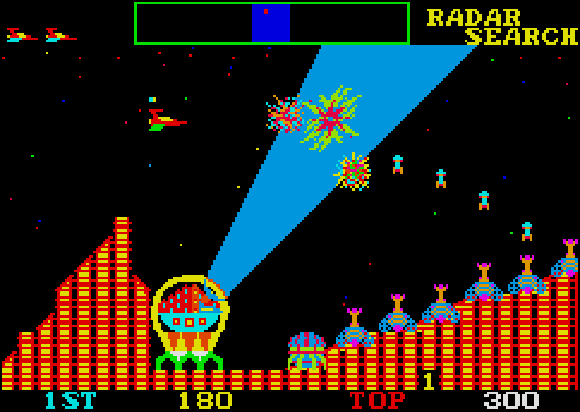

Screenshot of the attract screen from the arcade version of Defender.

In Gamasutra's August 2007 article, John Harris called Defender the "hardest significant game there is," remarking that such a demanding game seems "unthinkable" today. Although there are plenty of challenges in today's videogames, few require the intense coordination and Zen-like concentration necessary to achieve a high score in Defender.

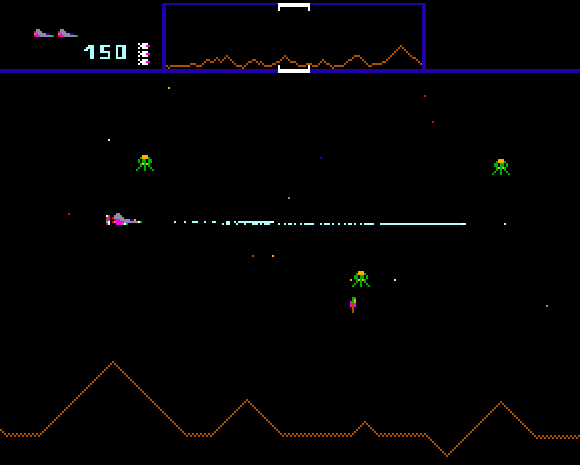

Arcade screenshot showing Defender in action.

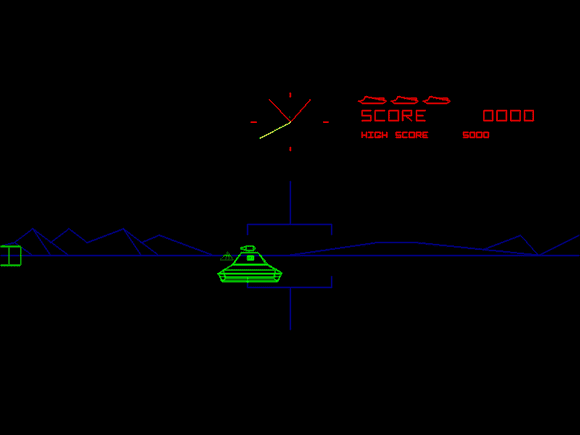

Screenshot from Atari's Battlezone, which is another classic game from 1980 that features a useful scanner for detecting enemies off screen.

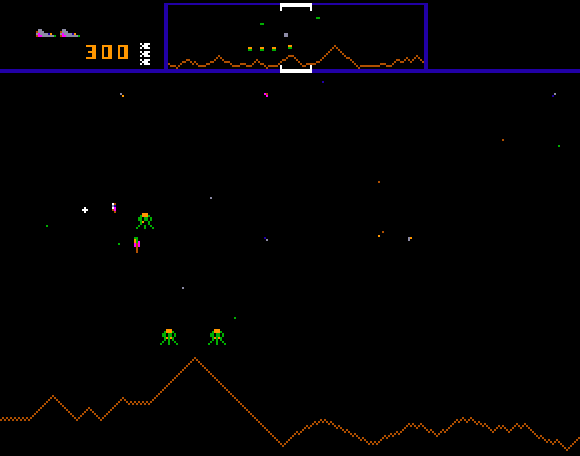

The primary goal of Defender is for the player to pilot the titular spaceship and prevent stranded Humanoids from getting abducted by aliens. These alien enemies include the Lander, Mutant, Bomber, Pod, Baiter, and Swarmer. Keeping the Humanoids safe and rescuing them from aliens was a formidable task to say the least.

The Defender was armed only with a relatively slow-to-fire, edge-of-screen-length laser, a limited number of screen-clearing smart bombs, and an unrestrained ability to randomly disappear into hyperspace -- perhaps reappearing to worse danger or even immediate destruction. Fortunately, tracking the Humanoids was simplified with an innovative scanner or "minimap" shown at the top of the screen, as well as a distinctive sound effect that played whenever a Humanoid was in danger.

The minimap, which became a common feature in other games, added a cohesive quality to the scrolling, multiscreen playfield. It was then up to the player to race to the Lander's location before it reached the top of the screen and destroy it without killing the Humanoid. If a Lander were successfully dispatched, the Humanoid would begin to fall, potentially to its death if the fall was great enough.

In that case, the Humanoid would go "splat" if the player could not catch it mid-fall. The player could then fly with the rescued Humanoid under the Defender until one or the other was blasted by an enemy or the Humanoid was dropped off safely at the bottom of the screen, where it would resume walking with no apparent destination. If a Humanoid was successfully abducted, it would transform into a crazed Mutant, presenting an even more fearsome enemy to deal with.

If all the Humanoids were captured, the planet exploded and turned all the Landers into Mutants, creating a scenario that all but the best players were unable to survive for more than a few seconds. Despite the amazing difficulty, it is this "catch and rescue" play mechanic that stands as one of Defender's best features and was mimicked in some of the better games it later inspired.

Arcade screenshot from Defender showing a Lander flying upwards with a captured Humanoid.

[1] Affectionately dubbed SHMUP (shmup) by some enthusiasts.

[2] From the multimedia retrospective on Williams Arcade Classics (Midway, 1995; PC, Sony PlayStation, and others).

[3] Defender's development was completed with the help of Larry DeMar, Sam Dicker, and Paul Dussault. Demar would also work with Jarvis on Robotron: 2084.

In a column for Gamasutra, game designer Manveer Heir stated, "In 1977, the Atari 2600 [Video Computer System (VCS)] was launched with a joystick that had a grand total of one button to use.

Today, the [Microsoft] Xbox 360 has sixteen buttons on their controller. In other words, about every two years, we get another button on our controllers.

This increase in interface complexity is the result of increased game complexity." Heir's statement is all too true, and is likely one reason why older games with simpler requirements and demands have regained popularity in recent years.

However, although Defender was not an easy or simple game, it was still converted to the Atari 2600 in a high-profile 1981 release that -- along with Space Invaders (1980) and Asteroids (1981) -- helped the system become a dominant platform.

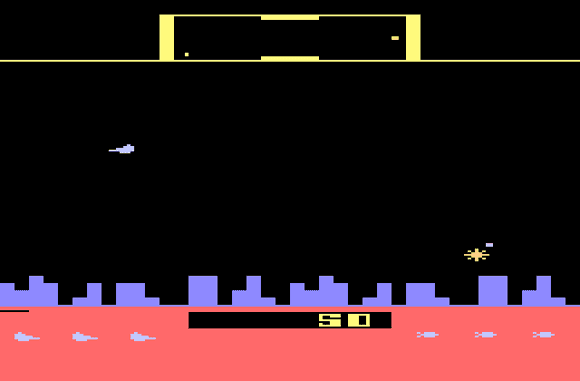

Besides an obvious reduction in sound and graphics -- the arcade version's mountains turned into blocky city buildings -- the control scheme was also modified to fit the platform's constraints.

The 2600's single-button joystick had to accommodate the arcade version's up/down joystick and individual Reverse, Hyperspace, Smart Bomb, Thrust, and Fire buttons. This change in control scheme results in distinct changes in both gameplay and flow.

The Atari 2600 version of Defender took many liberties with the license.

Unlike the arcade version, in which two or more Landers can kidnap Humanoids simultaneously, the 2600 version allows for only one at a time. Also, Humanoids can't be accidentally shot by the player and Hyperspace never results in instant death, as occasionally happens in the arcade version. Finally, the joystick in the 2600 version is used for all movement and thrust, and the single fire button is used to fire lasers, release Smart Bombs, and activate Hyperspace.

Smart Bombs are activated when the button is pressed when the ship is at the very bottom of the screen (behind the city) and Hyperspace at the very top (behind the minimap), making their overall utility questionable at best. A final result of the game's concessions to the home platform is that every time the player fires, the Defender ship disappears (essentially, one graphical image would replace the other), creating unintended possibilities for evading enemy hostility.[4]

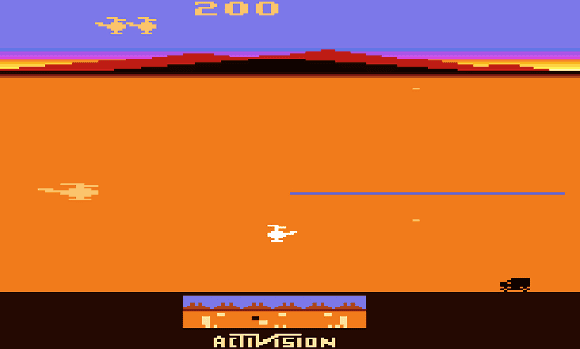

A later 2600 game inspired by Defender's gameplay is Bob Whitehead's Chopper Command (1982) for Activision. Whitehead kept the 2600's limitations in mind, and featured the type of audiovisual polish that distinguished the company on the platform.

Although not a particularly ambitious game in terms of mechanics, it nevertheless succeeded by being a highly playable, straightforward shooter that utilized the same type of minimap, inertia-based movements and high difficulty from Defender, albeit with the notable omission of the rescue component. In Chopper Command, the player is simply tasked with using his or her helicopter to defend a truck caravan from bomber jets and other helicopters.

Chopper Command was Activision's strictly action-oriented answer to Atari's conversion of Defender for the Atari 2600.

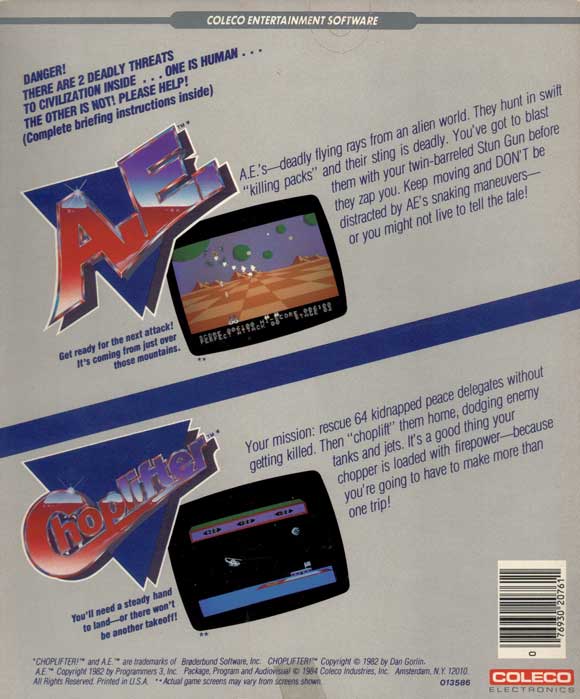

Dan Gorlin, on the other hand, with his much ported Choplifter (Broderbund, 1982; Arcade [Sega], Atari 7800, Coleco ColecoVision, and others) for the Apple II, made one of Defender's best features a critical component of his classic helicopter-based hostage rescue game. In an interview for the book Halcyon Days, Gorlin describes how the design for Choplifter developed from Defender a bit differently than one might expect:

"Being fascinated with helicopters, I started out by making one fly around using a joystick. It was really cool, so I kept adding things to shoot at. We had this local kid doing some repairs on my car just outside, and he used to come in and play with it. He was a big Defender freak, and one day he said, 'You should have some men to pick up.' I walked over to the laundromat and took a closer look at Defender to see what he was talking about -- never played it myself -- and damned if I could see any men, but took his word for it, and it seemed like a cool idea."[5]

Back of the box for the Coleco Adam The Best of Broderbund: A.E. and Choplifter, the former a type of Galaga clone (see Chapter 16, "Space Invaders (1978): The Japanese Descend") and the latter inspired by Defender.

[4] Other home ports generally kept most arcade features intact and allowed for more robust control schemes consistent with the target platform.

[5] See http://www.dadgum.com/halcyon/BOOK/GORLIN.HTM. Unlike in Defender, the tiny humans in Choplifter were easier to identify and better animated.

In Gorlin's design, the helicopter can face and shoot in one of three directions: left, right, and forward ("forward" means facing the screen, useful for attacking ground targets).

The player must use the helicopter to release the hostages, who are trapped in destructible prisons.

Once a prison has been breached, the helicopter must then carefully land and allow the hostages to board, one by one, until the maximum number for a run is reached or it becomes necessary to escape.

The helicopter must then take off, fly back to the base and again carefully land, allowing the freed hostages to leave one by one.

The process then repeats until all hostages from the level are freed or destroyed, preferably not by accident with the player's own helicopter.

Much like the ship in Defender, the player's helicopter in Choplifter is constantly under attack, this time from both ground and air enemies, with high difficulty being the rule, rather than the exception.

Entex's Defender electronic game, which was a popular dedicated handheld from 1982. Entex also released the now highly collectible and rare Adventure Vision tabletop videogame system in 1982, which was bundled with a Defender cartridge.

As with most legendary and popular games, Defender received more than its fair share of additional ports, clones, knock-offs, and enhanced variations.

Some of the best of these include Big Five Software's Defense Command (1982; TRS-80), Sirius Software's Repton (1983; Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64), Arena Graphics' Dropzone (1984; Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, Sega Game Gear, and others), Synapse/Atarisoft's Protector II (1983; Commodore 64, Radio Shack Color Computer, TI-99/4a, and others), and Logotron's Star Ray (1988; Atari ST, Commodore Amiga, and others), which became the officially licensed Revenge of Defender when it was later published by Epyx.

Of course, Defender was also influential for the side-scrolling shooter genre in general, which included Scramble (Konami, 1981; Arcade), where the player had to destroy fuel tanks to replenish their ship's supply while wreaking havoc; Parsec (Texas Instruments, 1982; TI-99/4a), noted for its speech-enhanced audio; Datamost's The Tail of Beta Lyrae (Datamost, 1983; Atari 8-bit); which featured semi-random levels, R-Type (Irem, 1987; Arcade), which became known for its impressive bio-organic graphics and boss battles; Parodius (Konami, 1988; MSX), which parodied the genre and its classic progenitor, Gradius (Konami, 1985; Arcade); and Gates of Zendocon (Epyx, 1989; Atari Lynx), which offered 51 levels to blast through. Despite their popularity, however, unlike Defender, most of those titles relied on more straightforward shooting-based gameplay and an excess of hazards for thrills.

Screenshot from the Commodore 64 version of Revenge of Defender.

The Magnavox Odyssey2's Freedom Fighters! (1982) was that platform's answer to Defender, and, instead of mapping controls to the console's keyboard, implemented an awkward two-joystick control scheme that worked best with two players at the helm. Image from the Freedom Fighters! Manual shown here.

Screenshot from Universal's Cosmic Avenger (1981), a difficult side-scrolling shooter that featured a minimap of limited utility. Defender directly influenced games like this and countless other shooters in a variety of ways.

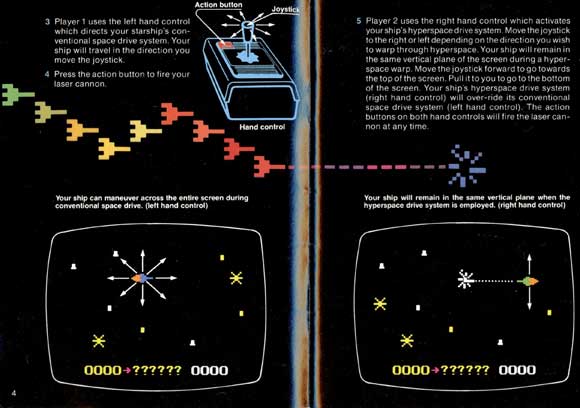

After Jarvis left to form his own company -- Vid Kidz -- with Larry DeMarthe, the two continued to design games for Williams, starting with Defender's 1981 arcade sequel, Stargate, which, for trademark purposes, became Defender II in later home releases.

Never reaching anywhere near the popularity of Defender, Stargate added new enemy ships, equipped the Defender with a limited-use invisibility (cloaking) device (a sixth button!), added two special stages after every fifth and tenth board, respectively.

It featured the titular Stargates, which among other things, transported the Defender to any humanoid in trouble and, under the right circumstances, allowed especially skilled players to jump ahead several levels.

This ability to jump made the game even more frenzied, and the best players felt it let them get one up on the game.

When asked about the inspiration for the game's Stargates, DeMar said the two "wanted something that would give some new appeal to the game [Defender], but that wouldn't be playable by the good players on Defender."

So the two "worked hard to develop a mechanism that would be good for the experienced Defender player, but wouldn't make them stay there for a long time."[6]

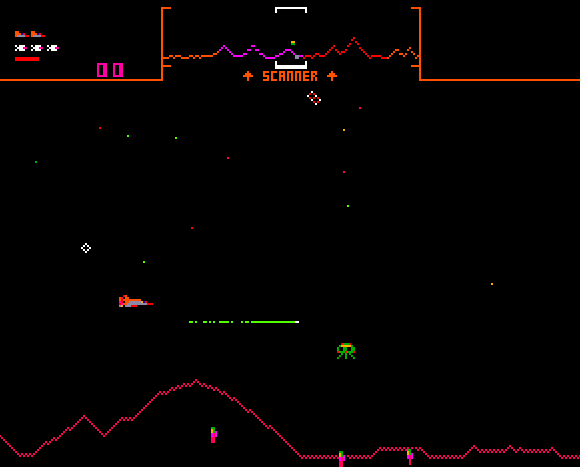

Screenshot from the arcade version of Stargate, which became known as Defender II for most home conversions.

Atari's 1984 conversion of Defender II, née Stargate, was a marked improvement over their earlier conversion of Defender.

A final -- though less direct -- arcade sequel, Strike Force, was released in 1991 through Midway to little fanfare.[7] While Jarvis and DeMar were on the staff, the game's main programming was handled by Todd Allen and Eric Pribyl. According to MAME's history file on the game, [8]

"Strike Force again has the player flying a spaceship over the surface of a series of two-way, horizontally scrolling planets, destroying enemy waves and rescuing humans from the alien invaders; with rescued humans hanging from the underside of the player's ship. Once these tasks have been completed, the mothership arrives to pick up the player's ship, together with any humans they have rescued. Players can decide which planets to attack, when to purchase additional firepower and when to attack the Apocalypse. Strike Force's graphics differ from the minimalist, stylish appearance of the first two games in the series; with full color sprites, multilayer scrolling and colourful, visceral explosions giving the game its own distinctive look and feel."[9]

Screenshot from the arcade version of Strike Force.

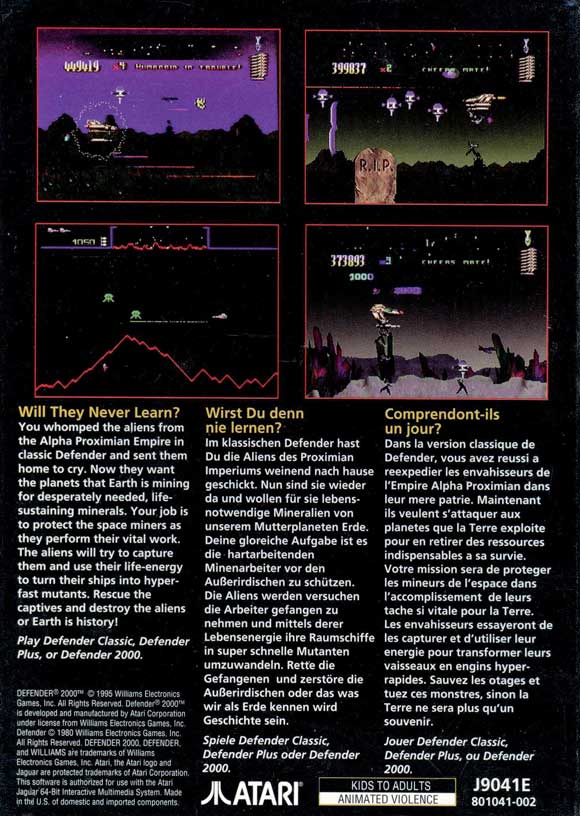

Besides the official home ports of the arcade games and the aforementioned Revenge of Defender, the Defender series would receive two more new official home entries: Defender 2000 (1995) and Defender (2002), as well as a 2006 release of the original arcade game on Xbox Live Arcade for the Microsoft Xbox 360, which added online options and a mode with sound and visual enhancements.

Defender 2000 from Llamasoft, published on cartridge by Atari for the Atari Jaguar, features a choice of three modes: Defender Classic (original arcade version), Defender Plus (audiovisual enhancement of the original with the option for helper droids to make the game a bit easier), or Defender 2000 (additional enhancements, including powerups).

The 2002 release of Defender for the Microsoft Xbox, Nintendo GameCube, and Sony PlayStation 2, took the series into 3D with a third-person, behind-the-ship perspective, creating a very different experience than its namesake. The Nintendo Game Boy Advance version retained the original's 2D perspective and included an option to play the original game, which some contemporary reviews indicated was the cartridge's saving grace.

Defender 2000 was one of several updates of classic arcade games on Atari's Jaguar console. Box back shown.

Although the series has long been surpassed in popularity in the modern niche of the shoot-'em-up genre, it was early games like Defender and each new generation of consoles that finally proved gamer adaptability to increasingly complex control schemes.

Of course, it can be argued that this complexity reached a point of diminishing returns and that's why more casual games and systems like the Nintendo Wii have proven so popular in recent years. Certainly, Bushnell's experiences with Computer Space and Pong (see the bonus chapters on Pong and Spacewar!) suggested that complexity was as bad as simplicity was good.

Nevertheless, Defender successfully challenged the idea that gamers couldn't handle or wouldn't play complex and difficult games in the arcade, awakening other developers to new, more sophisticated design possibilities.

[6] From the multimedia retrospective on Williams Arcade Classics (Midway, 1995; PC, Sony PlayStation, and others).

[7] In 1988, Williams, operating as WMS Industries, acquired Bally/Midway, and now operates under WMS as Midway Games.

[8] MAME stands for Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator. According to the MAME Documentation Project Website, "Its purpose is to document the inner workings of those pioneering games of the video arcade era. Remember Pacman, Space Invaders, DigDug, etc., well, they are all documented and what's more fully playable in the MAME project. You see, these arcade machines will not last forever, so the emulator and ROM Images are here to preserve these games."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like