Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A comprehensive look at the state of key reselling, including comments from G2A as well as a range of indie developers...

Last year, after something Proteus developer Ed Key mentioned on Twitter, we noticed that copies of our game Frozen Synapse were being sold on several sites that we didn’t recognise.

That’s not a pleasant moment for any developer: it instantly feels like someone is making a cheeky profit at your expense. The persistent background buzz of piracy is one thing but another company profiting from our games without our knowledge is an entirely different sensation.

It’s important to check these things out, though, so we emailed the sites in question to ask them if they had a valid distribution agreement with us and if they could show us a copy.

Fast2Play, Kinguin and G2Play are sites which are all owned by a company called 7 Entertainment. Fast2Play is a store where keys are sold to customers, whereas Kinguin is a “marketplace” which allows users to sell keys between themselves. G2A are a separate entity: their business also has both store and marketplace components.

All of these sites had listings for the game but were unable to supply any proof that they were genuine copies that we had authorised. We had never received a share of sales from any of them.

Fast2Play immediately responded to our enquiry by saying simply, “Product has been disabled on the store.” I asked them if this constituted an admission of illegal activity, to which I received no reply.

Frozen Synapse remained on sale on the rest of their sites until several days later, when more unanswered emails prompted its short-term removal.

It was at that point that Game Informer decided to write about the story, interviewing Ed Key and I about it:

7 Entertainment then responded to the article:

It was at that point that I decided to leave things. We’d achieved a commitment from them to stop selling keys from Humble Bundles for profit, a concept which was pretty much universally panned by customers and developers alike. The traditional indie response to situations like this is to spend our limited resources elsewhere, specifically on things which directly benefit legitimate customers.

However, some recent developments have caused me to renew my interest.

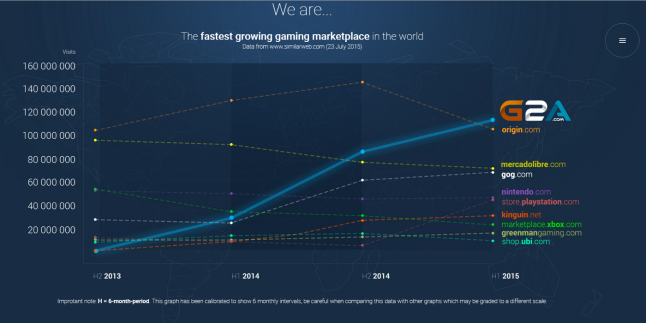

G2A and 7 Entertainment have taken out some very high-profile sponsorships, with a particular focus on esports and Twitch streaming. This kind of activity can be profoundly powerful in establishing the legitimacy of a brand; it seems to partially explain G2A’s rapid growth:

It’s not just indies who have tangled with the key resellers. Ubisoft got into a difficult situation with Far Cry 4 keys which were purchased with stolen credit cards and then resold via Kinguin and G2A. Kinguin responded by effectively blaming EA and then appealing to gamers “who simply don’t want to pay publisher suggested prices”. As many players had bought their keys via reselling sites, believing that they were legitimate, Ubisoft were then forced to backpedal.

Polygon published a comprehensive look at the matter and revealed the confused, chaotic nature of key marketplaces. Apparently, nothing has changed since the original Game Informer article: publishers and developers ignoring the situation has simply allowed these sites to grow.

I’ll begin by taking a look at the legality of reselling, then move on to some developer perspectives and finally conclude with a few thoughts of my own.

The question of legality here is paradoxically simple and complex.

If you believe that the EULA’s which Valve, Humble and other distributors use are valid and enforceable, then reselling is clearly prohibited. If not, then the situation is far more vague.

If you’re content with that as a summary then please feel free to skip this long section and continue at “The Indie Perspective” below! If you’d like a full exploration of the legal issues then read on…I now wish I’d written this in Twine.

I spoke to Tilly McAdden and Alex Tutty from Sheridans law firm in the UK. Tilly and Alex specialise in games and technology; they deal with these issues on a daily basis.

Could you give me a general summary of the issues here?

For the purposes of these answers we will use the terms “sell” and “sale” etc. but in fact what we are talking about is paying money for a key which provides access to a piece of software which is covered by a licence.

More specifically, in relation to downloads and software keys, when you buy these in order to use them you need to download the software, which involves making a copy of it.

The unauthorised reproduction or copying of proprietary software products in most cases amounts to copyright infringement. This is because, generally speaking, all uses of the software like many other copyright protected products (physical and digital) require the express permission of the rights holder. So it follows that if the desired use of the game (such as reselling) is omitted from the End User Licence Agreement (“EULA”), then it cannot be used in that way without further authorisation from the rights holder. Or alternatively, where the EULA does include terms which permit the further reproduction of the software or game, you can indeed make a further copy as long as it is used within the prescribed terms of the EULA.

At the end of the day, any use of the software or game outside the specific terms of the EULA would not be permitted and in the instances of any transfer, which involves making another copy, would amount to copyright infringement.

It is more akin to lending something under certain conditions rather than having outright ownership. It is possible to sell physical software but this is not the case in these examples of digital downloads of games.

What is the current legal status of reselling (defined as buying from a legitimate distributor and then selling the key elsewhere) game keys or licenses in the EU?

What we are talking about here is the reselling of a licence to use game software. The current status in the EU is that the terms of the End User Licence Agreement and under which the game is “sold” govern what you can do with it unless the terms are invalid due to being contrary to current law.

If you have a physical product like a book once you buy it you do own it and then you can resell it (otherwise car boot sales would be even more dodgy). What you cannot do is make a copy of that book and sell that. You cannot also copy your book, destroy the original copy and then sell the new copy. Also you do not have rights in other versions of that book or other copies of it. You just have your one copy.”

How would you respond to people citing news posts from the gaming press as a counterpoint to that? For example, the cases cited by Engadget and Destructoid in 2012?

These cases do not support this. When they were first published there was a suggestion that they might, but in the technical (and relevant) legal bits of the judgements it is not there. In these examples, the exact cases are not mentioned, so I have answered the question but I have also included the most recent and important cases, as they make a special case for games.

“EU Court Rejects EULAs, Says Digital Games Can be Resold”

This case is very specific to its facts. It involved non-games software that could be freely downloaded but needed to be activated via a code. The defendant was selling licences including the codes that it had bought it bulk and passing on the discount. The court said that it could resell these licences but interestingly it explicitly stated that where it had bought in bulk for its own use it could not sell on separate licences which were part of this block.

“EU Court Rules it’s Legal to Resell Digital Games and Software”

The case we should be talking about here concerns Valve (VZBW v Valve). After the case described above which stated that “resale was allowed in certain cases” VZBW tried (again) to have a court decide that games could be resold. Specifically VZBW asked the court to find that Valve’s terms which banned the trading of games between users were unenforceable.

The German court did not agree that they were unenforceable and therefore held that Valve could ban the resale of games in its terms.

In another related case (PC Box) the European Court also decided that games software should also be dealt with separately to more functional software as it contained graphical works. Personally I think that this complicates the issue (and in the favour of those who want to restrict software reselling) and will probably be ignored in subsequent judgements.

There are cases and statements that suggest the EU is trying to get to a position that might allow reselling but as it currently stands this is not the case if it is prohibited under the terms.

If a distributor’s EULA or Terms and Conditions doesn’t explicitly prohibit reselling, is reselling allowed then?

If there are no restrictions e.g. it says “you are granted a licence” and there is no mention of “limited, non-transferable” or similar i.e. it is silent on the issue. In this instance then the licence would be transferable unless it could be implied that it was necessary and obvious that it would not be a transferable licence. When this would be would depend on the circumstances surrounding it and the sale.

What do you think of claims that the prohibition of reselling is “unenforceable”?

As described above I do not believe that prohibiting reselling is unenforceable and would say that the opposite has been stated to be the case in the German courts (but interpreting EU law). Of course the law may change and each case will turn on its own facts but it is certainly not unenforceable. It may be difficult or impractical to enforce but that does not mean that it is unenforceable.

If a site set itself up as a marketplace for individual sellers to connect with individual buyers, requiring the sellers to sign a disclaimer saying that they had full rights to sell the game, what would be the legal position there for both the site and its users?

This makes the case to be very similar to eBay or other marketplaces. If a user states it is legal then the marketplace can rely on it. However, if they have actual knowledge that this is not the case (either before or during the sale process) then they are required to remove it, which is the case for infringing items for sale on eBay.

It is also worth noting that should the sale in fact not be legitimate the user may be targeted by the rights holder directly of the products and they in turn would have to take action against the online seller.

How about other territories? Does it matter where the site is based, or where the customer is based? Is there any way that reselling can possibly be legal?

For other territories I am not aware if it is legal. In the US the position is very similar to the EU and it is going through the same process as the EU as it tries to decide how to move forward.

If a site is based in another territory but is making infringing content available in the UK (for example) and advertising to UK residents, then it does not matter where it is based. There is an infringement going on in the UK which would be actionable in the UK courts.

Any response to this Gamezebo article, which asserted that “while initially it sounds illegal, there is no concrete court ruling that says it is, in fact, illegal”?

As explained above, the sale of the product is in the firstly subject to the terms of the EULA or the terms of the original contract for sale in the circumstances of bulk purchases. There have not been any cases before the courts in respect of this practice for games, however, in the case mentioned above regarding non-gaming software (“Court Rejects EULAs, Says Digital Games Can be Resold”) the court was very clear on the issue of licences bought in bulk.

It stated that where the original software was bought as part of a large bulk sale for one particular entity and that was the basis of the unit price in the first sale, such products cannot be unbundled and sold on. Since this is a similar practice at hand here, subject to the original terms of the sale, should some rights holders take it upon themselves to challenge such sales, the parties doing the unbundling and reselling may find themselves liable for breach of contract and/or copyright infringement should this approach be upheld in respect of gaming software.

Is there anything that developers can do to prevent these sites from distributing their games if they would like them to be taken down?

If developers are concerned about the resale of the products then it would be worth speaking with the original distributors of the products in the first instance to see if any restrictions where included in the original sale. Should concerns remain, they should contact the website/reseller and query the resale products. Humble have changed the way that they sell bundles and we would expect further changes to be made to make it more difficult to resell keys.

If a developer’s game is being resold and it is prohibited under the EULA then it would be sensible to contact the marketplace where the games are being sold and demand that they are removed. If that market place does not expeditiously then they may find that rather than being able to rely on the protection offered by law and their reliance on their terms with the seller that they become liable.

Finally what would you say to people who still believe this is a grey area?

As outlined above, the outcome of cases involving the resale of licences and codes will be determined by the individual circumstances of each case. I am aware that this sounds like a lawyer’s response but unfortunately since each sale will be subject to differing terms or EULA’s that is the reality.

Unfortunately, the main consequence of the uncertainty impacts the buyers of used or unbundled games and keys. Many will not be aware of possible restrictions and they may find that when they try to access the games that the keys are not useable or valid.

In order to ensure that buyers are getting a legitimate sale it is best to ask questions of the seller to ensure that they are entitled to sell the product in that particular way. This will assist should the issue of the buyer’s knowledge become relevant at a later stage.

I spoke to several representatives from G2A, including their Head of Global Business Development Tomasz Lagowski and Head of Global Public Relations Jacqueline Purcell.

G2A agreed to consult among themselves and prepare statements responding to my questions. I allowed them first to reply to some of the issues raised by Sheridans.

What is the current legal status of reselling (defined as buying from a legitimate distributor and then selling the key elsewhere) game keys or licenses in the EU?

Legal, there is no case on point that would be binding in the EU that addresses the current legal situation. To take a position that the digital marketplace is anything other than legal is a very, very large stretch. The Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) ruling in UsedSoft v. Oracle (2012) clearly allowed reselling. To take a position to the contrary based on a low-level German court case VZBW v. Valve, which is still on appeal, is not in accord with current CJEU, the highest court in the European Union, and its legal interpretation.

If a distributor’s EULA or Terms and Conditions doesn’t explicitly prohibit reselling, is reselling allowed then?

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) answered this question clearly in UsedSoft v. Oracle (2012) — Yes reselling is allowed.

If a site set itself up as a marketplace for individual sellers to connect with individual buyers, requiring the sellers to sign a disclaimer saying that they had full rights to sell the game, what would be the legal position there for both the site and its users?

Much like any marketplace the responsibility for the legality of the product being sold rests with the actual seller — it is the seller’s duty to ensure that he can legally sell the product he has listed on the marketplace. This is the way all marketplaces operate, for example eBay, G2A, Alibaba or Amazon.

Would it be accurate to state that you’re currently refusing to remove our games from your store?

We are a conduit, a marketplace, for digital sales and are not responsible for the products listed by sellers, however, if we have knowledge that a product was illegally obtained we take action to investigate the matter and act appropriately. If infringement is found by providing a notice and takedown procedure just as on eBay, Amazon and Alibaba.

Alex Tutty from Sheridans responded to this:

“Usedsoft concerned a very specific case and set down certain criteria if reselling was to be allowed. These criteria are unlikely to be met by resellers of keys (which requires the deletion of all copies of the software by the original purchaser and other such things).

Also they are maintaining the relevance of VZBW v Valve in which the court indicated games were to be dealt with separately.

Finally there’s the point that Usedsoft obviously did not think that even with its procedures in place that it has a strong case to continue and withdrew its appeal and settled by signing a cease and desist to stop reselling.”

I relayed this response to G2A and also asked them some follow-up questions.

Can you describe how your marketplace works?

G2A’s marketplace, much like any similar marketplace such as eBay, brings together buyers and sellers of goods. G2A’s marketplace is primarily focused on facilitating the growing demand for digital games and allows over 50,000 sellers to list digital games that they own for sale.

G2A in continuing to lead the industry in distributing digital content is opening a “Brands Direct” portion of our marketplace to assist all game developers and publishers, big and small, to instantly tap into G2A’s preexisting network of over 6 million users.

Would you agree that the use of game’s intellectual property on your site is contingent on the legality of that marketplace?

The G2A marketplace is legal. As in any reputable marketplace, such as Amazon or eBay, the responsibility for the legality of the product being sold in the marketplace rests with the individual sellers on that marketplace. G2A’s Terms and Conditions, just as Amazon’s and eBay’s Terms and Conditions, require that any item listed by a seller is legal.

Would you also agree that if you had knowledge of users frequently reselling games when they had no right to do that, that would invalidate the legality of the marketplace?

We at G2A are firm believers in the universally held axiom that one should not punish all for the transgressions of one. Much like eBay’s marketplace would not, and in fact has not, been rendered illegal by the sales of unscrupulous users selling items that are illegal, neither would such an act render G2A’s marketplace illegal. When G2A is made aware of a user violating the law G2A, pursuant to its notice and takedown provision, takes appropriate action against such users in order to ensure the integrity of G2A’s marketplace.

What protection do you have against that?

G2A takes great pride in ensuring that transactions on the marketplace are safe and secure. As such, to prevent against instances of illegal or fraudulent conduct G2A has a well-established notice and takedown procedure. If a party feels that a product being offered for sale has violated an established law, the aggrieved party may contact G2A at [email protected] with the item details and the alleged law violated and G2A will investigate the matter (for full details please review our notice and takedown provision found in section 10 of our terms and conditions https://www.g2a.com/terms-and-conditions). Additionally, G2A complies with all legal regulations such as the Anti-Money Laundering requirements and Hong Kong Money Services Operator requirements.

So, can you tell me which EULA’s from major game distributors that you know of do permit resale?

Since you are based in London, we shall focus on European Union law. G2A’s position is that EULA’s that prohibit users from reselling items that they have rightfully obtained is not compatible with the ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) ruling in UsedSoft v. Oracle (2012) clearly allowing reselling. Moreover, such a restrictive EULA that prohibits a user from reselling an item that he possess is not compatible with the European Union’s intent of creating a single European market with the free movement of goods.

Section G of the Valve EULA states: “you may not distribute the Content and Services or any software accessed via Steam.”

Humble’s EULA “prohibits exploitation of products in any manner other than for your own private, non-commercial, personal use.”

So that would mean that no keys purchased via Steam or Humble are sold on the marketplace?

G2A’s position is that EULA’s that prohibit users from reselling items that they have rightfully obtained is not compatible with the ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) ruling in UsedSoft v. Oracle (2012) clearly allowing reselling. Moreover, such a restrictive EULA that prohibits a user from reselling an item that he possess is not compatible with the European Union’s intent of creating a single European market with the free movement of goods.

This is from G2A’s user agreement:

“6.b the Selling User are entitled to place and sell such products or services, especially by way of copyrights possession, and that it has all the necessary licenses, rights, permits and consents to their use, distribution, posting, publication, sale etc., in particular the right to sale through the Internet, online system, as well as that the rights are not limited in any way”

How is this compatible with the EULA’s I cited above?

G2A firmly believes that users who own a product should be allowed to decide if they want to keep it or resell it, just as the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) ruled in UsedSoft v. Oracle allowing for reselling.

Can publishers or developers check the validity of individual sellers?

G2A has a rating system in place where any user of our marketplace can quickly review a seller. At G2A we believe in protecting the personal information of all our users, and as you are undoubtedly well aware there are complex data protection laws that prohibit any organization from disclosing personal information of users. If a publisher feels that an item listed by a seller is violating the law, they may contact G2A at [email protected] with the item details and the alleged law violated and G2A will investigate the matter (for full details please review our notice and takedown provision found in section 10 of our terms and conditions https://www.g2a.com/terms-and-conditions).

What is to stop a user buying a key on Steam, claiming a refund and then selling the key on your store?

G2A has built a robust and customer service driven marketplace having invested over 20 million Euros over the course of the last two years to ensure a secure environment for all our users. If a seller has obtained title to a product illicitly and G2A’s investigation confirms this we will take appropriate action against the seller and ensure that the buyer has a working product or a refund. Sadly, much as in any marketplace occasionally such incidents do occur but buyers are backed by our G2A Shield and our proven track-record of making things right with buyers. In fact, in January, Origin and Ubisoft were struck by criminals who obtained keys illegally. Some of those illegally obtained keys breached our marketplace and were purchased in good faith by our users. When we were made aware of the situation we promptly reached out and either issued refunds or working codes to the affected buyers.

If I have a distribution agreement with a retailer, it would allow me to have my game taken down. What recourse do I have to get a game taken down from G2A?

G2A has a well-developed notice and takedown procedure for products that violate established laws. If you feel that one of your products is being sold by a seller, on our marketplace, illegally we welcome you to contact us at [email protected] and the matter will be investigated by our 24/7 multilingual support team.

I have a response from our advisors with regard to Usedsoft [Paul note — here I am quoting Alex Tutty, as above]:

“Usedsoft concerned a very specific case and set down certain criteria if reselling was to be allowed. These criteria are unlikely to be met by resellers of keys (which requires the deletion of all copies of the software by the original purchaser and other such things.”

The concept that must be reviewed is that of exhaustion. Exhaustion, is a concept that clearly applies to physical, tangible, goods entering into the stream of commerce in the European Union. Exhaustion is the concept that once a good is in the marketplace in the EU the initial right holder’s right to control circulation (resale etc.) of the good is exhausted. The EU applies the Exhaustion concept EU wide as nation-by-nation exhaustion would be incompatible with the free movement of goods — the single market — desired by the EU. As a point of illustration with a tangible object, the purchaser of a book in Holland is free to resell that book in Denmark. (see Article 7 (1) of Directive (2008/95/EC) and Article 13 (1) of Regulation (EC) 207/2009).

Just as the Court sought to establish a standardized definition of a “sale” which should apply regardless of whether the transfer is digital or analogue, it stands to reason that the Court would do the same for exhaustion in order to facilitate the free movement of goods. What is clear is that as digital goods are transforming the modern marketplace EU courts, and courts the world over, are struggling to balance the interests of developers, creators, artists and copyright holders with consumer rights and the free movement of goods.

“Finally there’s the point that Usedsoft obviously did not think that even with its procedures in place that it has a strong case to continue and withdrew its appeal and settled by signing a cease and desist to stop reselling.”

The key point from the UsedSoft case was the highest court in the European Union, the Court of Justice of the European Union stated that reselling is allowable. UsedSoft GmbH v Oracle International Corp (C-128/11). To attempt to reason as to why and under what terms UsedSoft decided to withdraw its appeal is pure speculation at best.

I believe G2A would acknowledge that their legal status in the EU hangs on a particularly dogmatic interpretation of a single case.

As an example of how other distributors reacted to that judgement, I found this response from Nintendo to a customer in the UK:

We deeply appreciate that you have been a loyal consumer of Nintendo products for so many years.

We take this as a sign that the quality of both Nintendo software and hardware has always met your expectations. This being said, we regret to hear that for the time being you do not intend to buy further games for the reasons pointed out in your email. We can assure you that we take your point very seriously.

In your email, you claim that the current digital distribution of Nintendo is not in line with the recent decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in UsedSoft v. Oracle (case no. C-128/11). Your reading of the judgment is that the principle of exhaustion is also applicable to Nintendo video games purchased in the eShop. Based on this assumption you conclude that it is not legally feasible to technically link the purchased games to your Nintendo account.

We have carefully considered your arguments and the aforementioned decision of the CJEU. As a result of our analysis, we unfortunately cannot share your understanding of the judgment.

In a nutshell, we would like to emphasise the following points:

1. The CJEU in UsedSoft only decided on a mere computer program but not on video games. A video game is a complex work which consists of multiple different elements in different work categories (audio-visual works like pictures, sounds, etc. as well as computer programs), i.e. a video game is a so-called multimedia work. Audio-visual works and computer programs are regulated under different legal regimes of copyright. The ruling of the CJEU only deals with computer programs. It does not follow from that decision that the first sale doctrine also applies to multimedia works. To the contrary, multimedia works have to be treated differently.

2. Even if the judgment was applicable to video games (which we think is not the case), the CJEU expressly allowed the distributors of computer programs to use Technical Protection Measures (TPM) such as product keys in order to avoid the uncontrolled passing of software from one user to another. The linking of software to the Nintendo account is such TPM. Hence, the current distribution policy of Nintendo is in line with the UsedSoft ruling of the CJEU.

We hope that these qualities, which apparently have convinced you to purchase and use our products in the past, will convince you to remain a Nintendo customer.

We do hope that this information is of benefit to you, we thank you for your kind attention and continued support.

Kind regards,

Nintendo UK

It appears that UsedSoft v. Oracle hasn’t swayed the big players in the games industry just yet.

I asked around to find indie developers who were interested in sharing their feelings about key reselling. Here are some of the responses:

Megan Fox, Glass Bottom Games

I treat key reselling much as I do piracy — I don’t condone it, but I’m not going to waste a ton of time chasing it around and shutting it down.

Would you go to one of the shady key reseller sites and trust them with your bank info? Because I sure wouldn’t. Which suggests that those going to the sites aren’t there by choice, but by having no other choice. I don’t think they have the luxury of thinking “will the dev get some of this,” they’re just thinking “I can afford to pay $5 on a game, no more, and OH MY GOD THEY HAVE THAT GAME I WANT!”.

Piracy and key-reselling are both products of a global society with a purchasing power differential. It isn’t like there’s one evil moustache-twirling guy.

Caspian Prince, Puppy Games

For the past however many years, we’ve basically been seeing a vast number of retail activations compared to actual sales. Of course, we’ve been in numerous bundles… so we can imagine that a fairly large number of “bundle retail activations” would be taking place… but I’m wondering whether the length of that queue should be such that our retail activations consistently outweighs our Steam sales by some large factor (currently > 5:1)

Here’s the last 12 months’ retail activations data:

Titan Attacks (retail) 38,650

Revenge of the Titans (retail) 10,047

Titan Attacks we might reasonably guess should be fairly big numbers as it’s been featured in bundles this year but the one that really sticks out like a sore thumb is Humble Indie Bundle 2. That was five years ago. People don’t just “discover” stuff they bought five years ago in those kind of numbers. From our perspective, we made approximately $5000 from those Humble sales (probably a bit less) but now it looks more like we’re losing $55,000 in Steam sales as a result. Which is of course the difference between me carrying on in game development and getting a job as software development manager here at Seamap… which is what happened.

In reality those keys are probably being sold by sites like G2A but for knockdown prices so we can’t really say we’re losing $55k in sales that way, probably some fairly smaller fraction of that like $20k. But then this is only one of our games… the other three are presumably going to keep selling via retail keys for years to come as well. Gah.

Anonymous Indie Developer

Basically, any of our games on Steam, for better or for worse, provide keys to users that allow them to use our non-Steam client if they wish.

Turns out copies of one of our titles were getting bought on Steam and then refunded, while the non-Steam keys were being sold on G2A.

Steam do provide us a list of these, which we can blacklist/deactivate for our non-Steam clients but by the time we had gotten round to doing the first batch, there were already around 7000 to be processed.

Of course this includes actual refunds but there was a big chunk of players who received a very nasty shock. I was sent numerous messages from people asking why they couldn’t play multiplayer anymore. As I understand, our support received 100+ tickets on that issue within the week.

We weren’t perfect in getting organised around this and probably could have reduced some of the damage done but it’s heartbreaking when there’s just nothing you can do and players who are doing us a service by keeping the game active have to be turned away. I guess a lot of them bought the game again but it really irks me that G2A profit from this business which is just negative to developers and players.

Almost gave them a piece of my mind when I saw them at Gamescom and probably would have done if I wasn’t there with the company.

Ashton Raze, Owl Cave Games

Both of our games can be found on key reselling sites; Richard & Alice and The Charnel House Trilogy, as well as the R&A/CHT bundle, although the bundle is listed as ‘out of stock’. I don’t think we’ve ever actually generated Steam keys for the bundle so I’ve no idea why it’s listed. I’ve never communicated with any of them about our games.

Honestly, I don’t have much of a problem with it. I’ve put those games out for sale (or distributed the keys), an action I was happy with, and I’m kind of okay with them being treated as things that can be resold. Don’t get me wrong, I get that it’s better if people don’t buy through key resellers, and I’d encourage any of our potential customers to buy through approved channels (even if it means waiting for a sale), but I also don’t feel like it’s my place to tell people they can’t resell a key they’ve bought.

If someone does buy from a key reseller, then I’d want to encourage them (through the quality of our games and developer/customer relations) to be there day one the next time we release a game, buying from one of our approved sellers instead of a key reseller.

But! Of all the things to expend energy on, I’ve come to feel that with key reselling, there’s a chance it might bring new audience members in.

Cliff Harris, Positech Games

I think it’s ultimately destructive to the relationship between developers and budget-conscious gamers because it takes away our ability to control the duration of time limited sales, ultimately meaning it becomes a bad idea for us to discount our games and give people on smaller budgets the chance to enjoy our work.

It’s also distressing to see your game apparently being sold in a store over which you have no control, no relationship, no contact, and no influence at all. How do I know my game isn’t being bundled with stuff I strongly disagree with, for example?

Kent Hudson, Developer of ‘The Novelist’

My feelings are complicated. On one hand, I have put my game into two Humble Bundles and participated in Steam seasonal sales, which means that a huge number of Steam keys were legitimately sold at a low per-unit cost. When I see the game on sale for a low price on reseller sites, I am assuming that the keys were purchased legally at a steep discount and that the sites are just playing the market in a straightforward “buy low, sell high” kind of way. In a free market, they have a commodity that they acquired at a discount and want to sell for a profit.

To be clear, my perspective would be completely different if the keys on these sites were acquired via shadier methods like hacking or theft. But for the purposes of this answer I’m operating under the assumption that they are buying keys during steep discounts (Humble Bundles, Steam Midweek Madness, etc.) and reselling them later for a profit.

That said, even if the keys were acquired through legitimate purchasing, I can’t help but have a visceral reaction to the fact that I poured my soul into that game for almost two years, and now some strangers somewhere are trading it without my permission or approval to make a few pennies. I know that isn’t entirely rational; in the cold light of day I know that I put a lot of keys into the market at a low price. I did that, like so many other developers, because that’s how the indie market works these days.

But the contract I feel I entered into as a developer is one in which I sell my game to people who care about it…So despite the logical economic aspects of key reselling, it still feels gross to see something you put so much of your creative life into turned into a commodity bought and sold by third parties solely so they can turn a profit without adding any creative value whatsoever.

While I acknowledge that I put Steam keys into the market at a low price, I did that in hopes of reaching more people and connecting with them through my work, hoping to provide them with a meaningful and worthwhile experience.

I suppose that’s the crux of it: it feels like an honest and legitimate exchange has been turned into something very crass without my permission.

The prevalence of key reselling highlights how the constant discounts and promotions in the current marketplace have really driven down the perceived value of games. Key reselling is a byproduct of a more central issue, and for our next game I want to look at ways to protect the value of our work more.

Lewie Procter, SavyGamer

Lewie is the proprietor of excellent discount hunting site SavyGamer. He wrote this blog post in 2014 as a response to his readers asking him about his beliefs on the key reselling issue.

No one forced developers to flood the market with cheap serials for their games, that was an action they voluntarily engaged in. Perhaps they might not have fully thought through the consequences of doing this; whilst I have sympathy for any developer who feels unhappy about this situation, they should be examining how their actions have led to it before pointing fingers at anyone else.

I felt this was a reasonably creative attempt to place the blame on the victim. The digital game market is such that discount sales are the main way in which developers make money, so failing to engage in them would be commercial suicide.

Lewie followed up with me on that:

My intent is not to victim blame, I’m arguing that if you choose to engage in capitalism by making a game and then selling it, you are opting to play by the rules of capitalism. Arbitrage occurs in all other markets, and I don’t feel that digitally distributed games should be exempt.

At the time, we were discussing his view of key reselling as a “grey area”, when I took the viewpoint, expressed by Sheridans, that it was demonstrably illegal in the EU. I suggested that it was inconsistent for SavyGamer to link to key resellers when it did not link to piracy sites. He responded:

If you genuinely think that the actions of Fast2Play are illegal, then perhaps prove it in court. Up until that point, in my mind they are innocent until proven guilty. This is the same affordance I would offer any retailer. I can’t just remove a deal from SavyGamer on the basis of an unproven allegation.

Like most developers, I reacted strongly against reselling when I first encountered it. It’s important to nuance your opinion over time and listen to other arguments, however.

I absolutely understand the desire to resell games. In an ideal world, there would be no regional price differences, no huge launch costs for AAA games, no need to wait for Humble Bundles and so on. Whether or not you believe these things are necessary or inevitable, a desire to exploit the arbitrage they create is a part of any economy.

One of the reasons that we at Mode 7 do pay-what-you-want promotions for our games is to allow them to reach customers who can’t afford launch prices. Humble Bundle has been brilliant in facilitating this. We understand that not everyone is able to pay full price for a game; a strong argument for resale is that it enables those customers to take part in the market. It is vital that developers account for this.

However, given that there are now legal options which benefit all parties, the argument that key reselling is the only way for some people to access the market seems problematic. With AAA games, that may well be the case, but indie titles are usually available at a range of prices relatively soon after launch.

Personally, I dislike the ridiculous nature of EULA’s, the means by which reselling is explicitly prohibited: I wish we could abandon them entirely and go for something clearer so that customers can actually understand. I also don’t think that mass key deactivation after the event is an acceptable response. As one G2A customer put it on a Ubisoft forum:

“I have bought it from a trusted retailer and you have no right to deactivate it because I payed money for it! “ (sic)

Punishing someone who doesn’t understand what they’ve done is rarely effective: this needs to be addressed in other ways, either at the original point of sale or through more effective education. The last thing that the industry should do, as with piracy, is to over-react and start hurting legitimate customers with byzantine copy protection or legal action.

While my opinion on resale in general is somewhat complicated, I have a much clearer view of its current practical implementation. The perceived ambiguity around the issue is being vigorously exploited by resellers and nobody really benefits apart from those taking advantage of it.

My general impression of G2A’s stance is one of trying to move beyond the perception that they are a “shady reseller” and into legitimacy: they say that they now want to reach out to developers. Global Head of Public Relations Jacqueline Purcell described her belief in “innovation before legislation”: G2A want to convey that they are changing the market rather than violating it.

I believe that if resellers truly want to become a legitimate part of the marketplace then they need to work hard to repair the significant damage that has been done by taking developer’s games without consent. Giving developers a cut of revenue is something which could change this.

Also, the existence of an unambiguous legal situation would trigger big distribution players, like Valve, Humble and the console platform holders to respond by permitting resale themselves. It would be out in the open. G2A have never, to my knowledge, discussed their specific legal position in public before: I hope this opens it up to debate.

Until reselling sites grew their userbase significantly in the past couple of years, there was no reasonable expectation that large-scale exploitation of the market was taking place; devs simply didn’t know it was happening and so couldn’t plan around it. Developers who took part in deep discounted sales or bundles long before the emergence of reselling could not possibly have predicted the extent to which its popularity would grow.

Currently, everyone is losing out: customers have to take the risk of using sites with very few guarantees about the product they’re buying; developers receive no payment; sellers are forced into a specific and controversial legal position without their awareness.

If key resellers are “pro-gamer” and “pro customer”, it seems odd they are compelling gamers to take on legal risk and then profiting from that. As you can see from the responses above, it’s clear that the legal onus is on the customer: the customer must decide what they think of the EULA and then they take on the risk of violating it, both as seller and purchaser.

The character of the market shouldn’t be altered by companies profiting from this sort of misdirection and exploiting the limited resources of developers. This is different from MP3-sharing or piracy which were largely consumer-driven phenomena: it’s motivated entirely by profit.

If we are going to change to a system where reselling is permitted; developers will need some time to adjust. While we’ve seen positive signs from distributors like Green Man Gaming, there is no meaningful way to predict what would happen if that were to be scaled up. Retail used game sales don’t provide a good indicator: it is so radically different from the digital marketplace that attempting to use it as a data point is fatuous.

It should currently be possible for developers to exercise our rights and easily opt out of having our games listed on sites like G2A. This would be a situation which works for everyone: it would mean that individual devs could make the choice themselves and their customers could take it up with them if resale was a necessary option when purchasing a game. There would be communication and fairness: I don’t accept that G2A’s offer to accept formal takedowns for specific reasons is sufficient here; it seems like a shield against litigation rather than an attempt to reach out. They still maintain that their store is legal and absolutely refuse to delist games on the basis that sales violate the EULA’s of other distributors.

Some developers are keen for major distributors to switch to time-limited keys in order to prevent reselling. I feel like this would be disappointing, as it’s effectively anti-customer: it’s nice to have gift copies of games hanging around to be discovered later; it would also be good to avoid issues where people forget to register a game and then lose it later on. The absolute last thing I would want to do would be to introduce annoying secondary constraints to try and stop this practise; in all this we should still be putting the customer first.

In fact, I’ve resisted writing a piece like this for a long time because, ultimately, we need to listen to what customers are saying rather than try and clamp down on illegal behaviour post-hoc. I’d love to focus more on things like the number of people who have bought my music after pirating it because they wanted to support me. I have been very open to anyone streaming or using my music for profit on Twitch or YouTube, providing that they give me a link or a credit, for example, despite the fact that prior to me making those declarations, the practise was technically illegal. I see these as positive market developments — things which benefit both producers and consumers — I wouldn’t want anyone to think that we are simply arbitrarily against any changes in the way digital content is sold and consumed.

Resale could be an enormous change for the games industry. I’m heartened by G2A‘s assertion that they want to work more with developers: to avoid seeming disingenuous, they must now back their words with actions. I thank them for their open and in-depth participation in this article; they were keen to stress that they are happy to discuss these issues with any developers who wish to contact them directly.

I hope that this is a small step towards a real conversation that can lead to a fair and healthy marketplace for indie games.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like