Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The recent patenting of the Nemesis system in the Middle-Earth series is a blow to the ecological system of entertainment, where the game business runs the risk of painting itself into a corner.

Many of the things I will say I've said before, but in different versions. However, I wouldn't bring up the conventions regarding the sharp line between the narrative and the game if it weren't due to a recent patenting of an engaging game pattern. So hang in there as I intend to clarify a few things concerning game creators' freedom within entertainment to explore and express themselves as meaning-makers to engage and motivate others. All links are collected at the end of the post.

This post is inspired by my brilliant fellow game- and narrative creators Shelby Carleton and Aidan Herron, who invited me to their podcast, Panic Mode, to explain what it means to approach game and narrative design from a cognitive perspective.

As game creators, we all have a cognitive approach in how we bear in mind the player’s thinking, the medium/technique, and style as possibilities to convey experiences and feelings. The only thing I do is visualizing our thinking and offering methods to control the design process in how we navigate through space to engage and motivate players.

Over the years it has been difficult to explain the extent to which the sharp line between the narrative and the game influences creators' opportunities to explore narrative possibilities beyond conventions. In order to bridge the gap between the contrasting convention of the static and scripted story structure and the dynamic and emergent data structure, the cognitive approach has been very helpful because it explains the interplay between our thinking, meaning-making, and emotions interacting with the computer’s learning.

Static story structure

---------------------------

Dynamic data structure

Instead of pushing the beliefs causing the border, I've embraced an evolutionary approach convinced that the creators' ecological system within entertainment will gradually bridge the gap. But when Shelby and Aidan wondered if I could give an example of a game that suffered from a lack of coherence between narrative and game design, the border made itself known.

I couldn't give an example as the answer was bigger than its parts.

Being a hybrid in the game business by having one foot in traditional storytelling and the other in computer science, I continually follow the evolution of a narrative understanding as my job is directly affected by the conventions of the narrative's behavior and appearance.

For example, as a narrative designer, even with a computer science background, I'm not expected to work with data flow modeling conveying the engaging and motivating forces into dynamic experiences through systems and mechanics. Exceptions are the specific story systems of branched plotlines and dialogue trees, encouraging choice-driven interaction arriving at alternative outcomes. Still, those systems proceed from the conventions about the narrative's static and scripted appearance, whose so-called embedded behavior constitutes a motive among game creators to seek the emergent gameplay structures.

I define the expectation space created by narrative conventions by drawing an interface between "screen-work" and "data-work."

Screen work

-----------------

Data work

Screen work is when you are expected to give conflicts, characters, and the world an engaging push by adding a story, dialogues, and visuals to mechanics and systems.

Data work involves modeling the data flow, forming engaging and motivating experiences through systems and mechanics.

The interface between the screen work and data work helps me navigate (understand) the client's desires when scaling and scoping the space of possibilities beyond conventions.

If a client expresses a desire to create engaging and motivating experiences (I haven't met anyone yet who doesn't accommodate those goals) and their request is "screen-work," I'm doing the "data-work" anyway.

The reason I do the "data work" is to show how the two motivating modes, the extrinsic or intrinsic motivation to learning, affect the drive of the player's behaviors and actions.

Extrinsic motivation - the act is driven by external rewards

------------------------------------------------------------------

Intrinsic motivation - the act is driven by internal joy

An extrinsically motivated design doesn't profoundly affect the player's drive like intrinsically motivated learning. The positive effect on the player from an intrinsic-driven design we commonly call exploring, an internal activity of orientation to understand by making sense of the causal, spatial and temporal links (see Hands-on guide: Predicting players' thinking).

A common misconception is that you can have an extrinsically driven design and add the story's causal network to deepen the motivating core drive. However, you can't expect narrative creators to "push" mechanics and systems by cobbling together the motivating core by attaching conflicts, characters, and dialogues to mechanics and systems.

The best is to do both the screen- and data work, as then you can form all parts into a whole to meet the desired outcome of a motivating core when setting the goal of what the player should experience or feel.

I recommend reading the writer Rhianna Pratchett's experiences from being expected to patch the narrative (story) to mechanics and systems. The backwardness is tangible if you are aware of the interface's expectations of narrative workers. The interface between writers and narrative designers can also become quite fuzzy due to the expectation interface, which Molly Maloney and Eric Stirpe describe in a GDC talk.

An intrinsic motivating mode is preferred because it proceeds from a cognitive friendly approach, requiring systems and mechanics "to listen in on" the player's thinking, learning, and meaning-making by observing how the player processes causal, spatial, and temporal links when navigating through space.

I'm sure many of you have heard the GDC founder Chris Crawford's Dragon Speech from 1992 on how you should make the computer appear as if it is listening (understanding). Another term often associated with the mentoring of a cognitive-friendly design is instructional scaffolding.

Worth noting if you are into research, the two examples above emerge from two different fields: Natural science and Humanities. Both fields engage in cognitive aspects of learning - the computer's (animal's) and human's learning. To understand how the narrative as a meaning-making mechanism comes into play, you need to knock at the semantic and linguistic scholar's door. To follow a scientist's progress bridging human- and computer learning, I recommend keeping an eye on Peter Gärdenfors, senior professor in cognitive science at Lunds University, Sweden (see also Putting into play and the seven-grade model of causal cognition).

An example of a game system listening to the player's meaning-making in how the computer learns/understands and responds to human learning is the Nemesis system in Middle-Earth: Shadow of War (2017).

Middle-earth: Shadow of War Monolith/Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

Middle-earth: Shadow of War Monolith/Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

The system proceeds from a "data work" of forming the computer's technique and style (graphic, audio, UI, controllers, engines, processor, RAM, and so on) into a cognitive-friendly scaffolding listener of how you simulate the computer to respond to the player's learning and meaning-making.

The system is said to be procedural by picking up the player's behavior of winning, losing, or fleeing and letting the orc objects remember and respond to the player's decisions and actions. Cognitively, the merging of human - and computer learning is prominent in how you model data flow to listen and remember player's internal and external activities over time (see Hands-on guide: Predicting players' thinking).

To get an idea of what a cognitive friendly listening system means, I recommend checking the video game journalist Mark Brown's Game Maker's toolkit on YouTube: How the Nemesis System Creates Stories.

The dream of stepping into another world to experience the story of being a hero defending and defeating evil has been a part of game development since the beginning. From a hybrid perspective, the dream has given rise to expressions such as open, emergent, and procedural spaces as a contrast to the so-called linear, embedded, and scripted dramatic story structure.

Proceeding from the desire to create an "open space" instead of the scripted dramatic structure created by an author has inspired conceptions about the players being their own storytellers. It is, of course, the player's thinking and meaning-making one refers to. However, as conventions about the narrative as scripted and authored are so strong, the possibility to access the player's thinking, i.e in the interplay between human learning and the computer's understanding, is concealed.

Unconsciously, the concealing of the cognitive activities on how we create meanings as meaning-makers has also maintained the gap between "data workers" and "narrative workers," which the narrative designer Edwin McRae expresses as follows:

"I personally think that procedural generation is a wonderful breath of fresh air, blowing away a lot of stale thinking and stale storytelling in the games industry. To be honest, it freaks the shit out of many a narrative designer. Why? Because it's impossible to rely on tried and true structures like "3 Acts" and "The Hero's Journey" when anything could happen in the game at any time."

Considering the interface between screen work and data work, what "scares the shit out of" narrative designers is probably the expectation of producing well-known story structures like Scheherazade factories until someone comes up with a new idea of making the story structure less scripted and narrative workers less useful.

What makes the Nemesis system's procedural behavior different from the scripted and embedded story structure concerns time and space. For example, if the player has won over an orc object, the object will seek vengeance over time. This "overtime," or as Edwin McRae expresses it, "any time," of how objects occur in space and time, signifies the so-called procedural behavior in opposition to the scripted and embedded narrative's static appearance.

Brief description of the opposing elements from a hybrid's perspective:

Scripted/embedded

The objects (characters) in a scripted and linear story structure are kept strictly to a dramatic order deciding objects' appearance and behavior according to a predetermined timeline (influenced by causal elements of turning-points, plot points embedded by acts).

Procedural/emergent

In a procedural appearance and behavior like the Nemesis system, space is added to time making the objects' occurrence "less scripted". Their memories of the player's action are released from a predetermined place on the timeline. Simply expressed, the objects' memory is a part of space "over time" and can occur "any time" from a player's perspective.

If you wonder about the term procedural, the procedural memory is connected to human learning (semantic scholars will probably agree), and the procedural generation, which Edwin mentioned, is more computer-focused. It's, however, a great example of navigating research concerning cognition.

As a hybrid, I dream of a cognitively friendly unity between minds in time and space, enabling creators to jointly explore possibilities by utilizing the medium, embedding the dynamic and motivating forces to etch the experience on memory.

During the conversation with Shelby and Aidan, the only answer I had to which obstacles games are facing, was the gap between narrative- and game creators. We collectively agreed to tear down the border to unite creators to explore possibilities beyond conventions. It was kind of wishful thinking, brushing aside doubts as to how we are supposed to tear down something that people seem pretty comfortable with.

After all, even in entertainment, conventions are not formed for nothing.

It’s actually quite tricky to explain the advantages of having a cognitive approach to both narrative- and game design. The term narrative inevitably makes the thoughts wander off to the dramatic story structure and Hero's journey like a magnet responding to iron.

Since I got hold of the 7-grade model of causal cognition three years ago, which explains how our thinking and meaning-making work (see also Putting into play and Peter Gärdenfor’s research portal), I’ve been able to bypass mentioning the narrative and proceed from how we formulate our thoughts and create meanings (narratives) to engage and motivate others (including ourselves).

But if we want to understand how experiences are etched on memory, in the mind, and emotionally, we need to understand how narrative possibilities emerge from how our meaning-making interplay with the game’s technique and style.

A narrative possibility from a cognitive friendly perspective is how you utilize the medium to convey dynamic and motivating forces by employing contrasts of familiar and unfamiliar elements to engage feelings that are etched on the memory.

Some call the engaging effect "subverting players' expectations" to keep a game from being predictable, but I call the impact sticking to the memory a surprise.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The surprising formula of a narrative possibility

I’m using a color fill of the familiar bar to illuminate a space we are familiar with to visualize an unfamiliar element we don’t expect. The upper bar is almost complete; there is little room for surprises as we are already familiar with it. However, the lower one is hardly filled at all, which means there is plenty of room for unforeseen events.

Familiar elements are experiences and knowledge we’ve built over time from learning—the experiences we store in our memory. Memories can be individual and detailed, but some are very general and work as a collective agreement and constitute our expectations on how things shall behave and appear.

Unfamiliar elements can only appear in relation to familiar elements. When you work in entertainment, your job is basically to make familiar elements appear in an unexpected manner. The more unexpected, the more powerful surprise.

Technically and media-wise, games and films differ hugely. What doesn’t diverge is the shared desire between creators in entertainment to engage and motivate the audience by employing narrative possibilities to add something new to an experience to trigger attention and engagement.

Considering other options than adding something new to the old is unthinkable for any creator in entertainment. It makes the narrative possibilities propel the ecological wheel of a self-regulating production of new experiences.

The effect you create is usually bound to time and space, and after it's consumed, it becomes a part of the familiar and expected.

There are examples of artists whose narrative possibilities have a delayed effect. Vincent Van Gogh might be the most famous artist whose unawareness of today's success is often mentioned. In contrast to poverty and failure, money and success are common narrative elements used in stories about artists' lives and the timing of their ideas. Apart from myths and stories, timing and balancing of a narrative possibility is always a part of a creator's work. From an intrinsic motivating perspective, you can always surprise yourself as a creator to keep up the drive. We commonly call it passion.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Self-portrait: Vincent van Gogh 1853-1890

Since it can be hard to discern the narrative forces creating the surprise, you can recognize how well the effect is etched onto people's memory, including the emotional memory. So narrative possibilities go pretty deep, making it hard to precisely tell what created the impact, but also when, why, and how, as people accommodate different meanings.

A simple example of a narrative possibility conveyed by the film medium's technique and style is Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994). It can be debated for ages what exactly made the film stick out, media-wise: the dialogue, editing, cast, or soundtrack. But the fact that people remember a line or feeling from the moment of experiencing the film is what counts. This kind of durable memory is a creator's dream but not an incentive as such.

Pulp Fiction, directed by Quentin Tarantino, Miramax Films, 1994

Pulp Fiction, directed by Quentin Tarantino, Miramax Films, 1994

From a creator’s perspective, the critical issue of narrative possibilities is how the emotional effect of balancing the expected and unexpected impacts memory and beliefs.

The impact of Quentin Tarantino’s films could lead you to believe that he was the only one in the nineties who could write rapid-fire dialogues. But while the surprising effects of his creation are perceived as a novelty, these are merely an expression by someone who sought to explore the narrative possibilities of creating something unexpected in contrast to the conventions of the time.

From a broader perspective, the ecological system of entertainment is not one person's work but a collective tacit agreement. Considering the consumable aspect of experiences, creators know they will be compared with others unless they add something original. In this way, the entertaining system regulates itself by continually moving from the old to discover the new to "let the show go on".

The cognitive exploration cycle of narrative possibilities is more prominent within game development by utilizing the computer's technique and behavior to convey mechanics and systems into new versions.

Developing a game is a constant balancing of familiar and unfamiliar elements related to the players' level of learning. The technique conveying the experience shouldn't be noticed but be perceived and conceived through the style in regard to what the player should experience or feel.

For example, the Nemesis system was a narrative possibility explored long before Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor was published in 2014 whose old system evolved and generated Middle-earth: Shadow of War 2017.

The familiar here is represented by the theme and genre of combat between good and evil based on Tolkien's world.

Middle-earth: Shadow of War Monolith/Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

Middle-earth: Shadow of War Monolith/Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

Recently, I have been taking a closer look at the unfamiliar element of the Middle-Earth series's Nemesis system as its surprising effect had an unforeseen consequence.

Shortly after the interview with Shelby and Aidan was published, I received unexpected news. The Nemesis system had been patented.

Compared to familiar copyrights, product-, and trademark patents, the unforeseen event from a game creator’s perspective was that the Nemesis system’s patent unexpectedly covered a method forming a gameplay pattern (check Gameindustry.biz One patent to rule them all).

From my hybrid perspective, legal workers had just stepped into the narrative domain, inadvertently giving the answer to what makes games suffer from the sharp line between the narrative and the game.

When reading about the background of the patent with my cognitive friendly lense, I recognized how the argument of the Nemesis system's novelty, to never have been seen or done before, actually illuminated the convention, as the interface between “screenwork” and “data work” has traditionally been created through a notion of the narrative as a scripted story structure.

Just to give you a taste of the patent….

"To add interest to game play, non-player characters have been programmed to act differently depending on which branch of a narrative tree a player is following. If the player decides to take a certain action in a narrative story line, the non-player character will follow a corresponding script. If the player decides to follow a different branch of the story line, the same character may execute a different script. (...)

In games that permit player dialog, non-player character have been programmed to consult a database of past player conversations, identify similar conversational topics, and determine what to say past on past similar conversations. (...)

While these techniques for programming non-player characters may make game play more interesting, there are many aspects of non-player character development that prior methods are unable to achieve. The interactions and personalities of actual human characters are extremely complex, and prior system have not been able to provide a realistic degree of complexity that fits in appropriately with the flow of game play.(...)"

The patent basically describes the game creator’s challenge to make the scripted story structure dynamic by using the predecessor’s attempts as an argument to illuminate the patent’s innovation.

Enclosed in the patent are descriptions of how a computer works when processing non-player characters (objects). From a cognitive friendly perspective, it means that an intrinsic motivating mode to engage the player's internal activities is a part of the patent of how you allow the computer and player to interact.

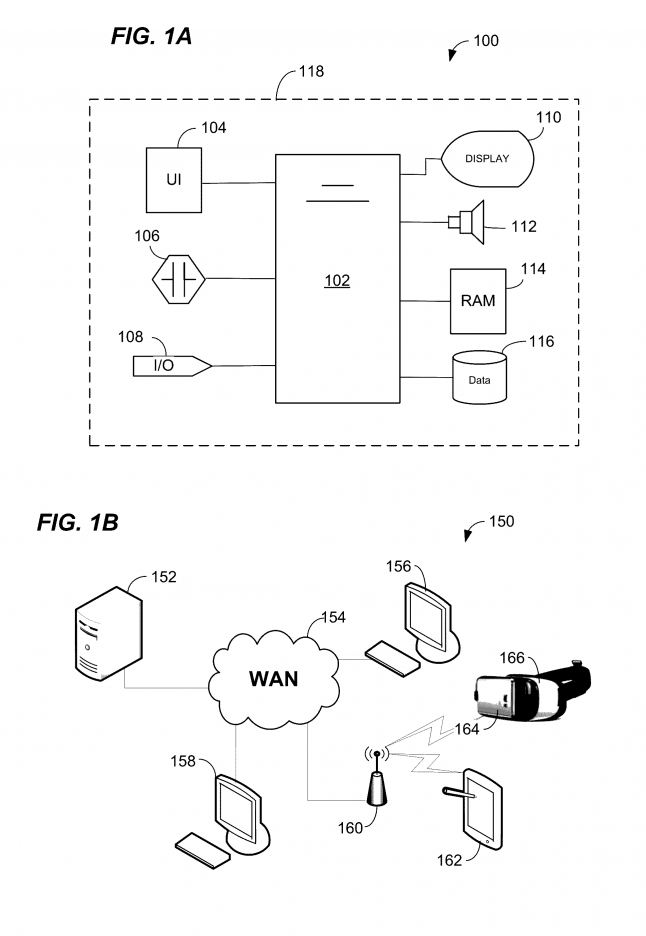

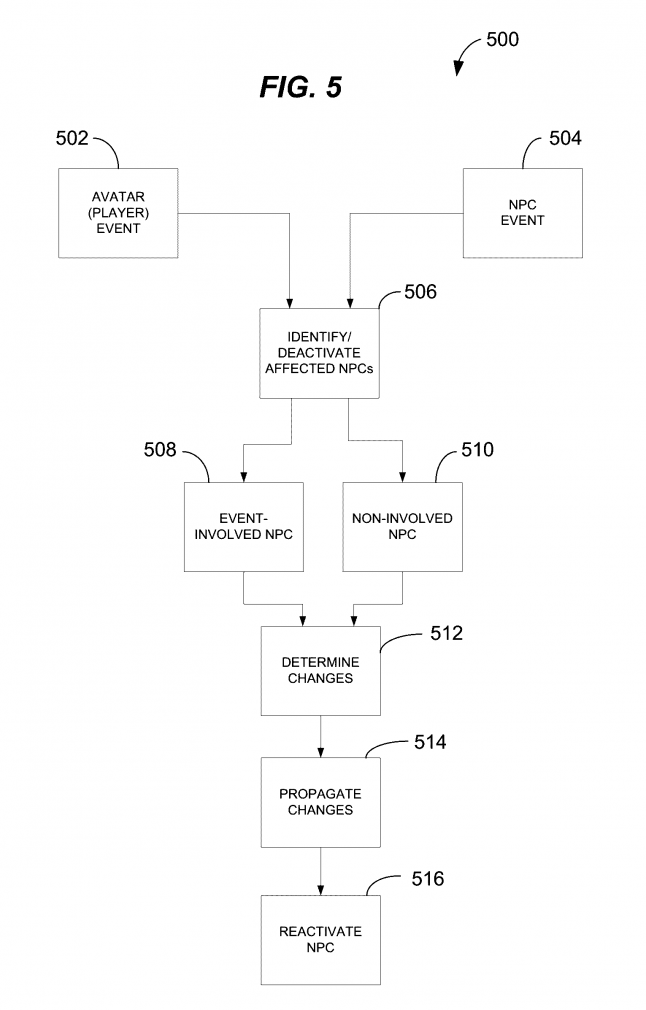

Ex from patent US20160279522A1 showing computer, player, and objects interactions

The patent's core also concerns a memory hierarchy by the computer's response over time. From a hybrid perspective, human learning also has a response time when making sense of the causal, spatial and temporal links, which you consider when cognitively modeling data flow by making systems picking up and responding to player's behaviors, forming the mechanics.

I wasn't the only one reacting to the unexpected news about the Nemesis system's patent (see examples, IGN, Eurogamer, Geekwire). Still, it is unknown what the patent actually means to future explorations of narrative possibilities as no one has yet tested the legal aspect of the pattern.

However, the collective response from the game community didn't go unnoticed. The strong reaction came from a feeling of being deprived of the opportunity to express oneself through mechanics and systems.

From a hybrid point of view, it wasn’t the unfamiliar of the medium’s technique and style, i.e. the data work, that captured my attention. It was the expectations on the static story structure and the surprise of making it dynamic that rocked my tacit ecological agreement of letting the show motivate itself.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Static story structure constituting the base to an innovation

Static story structure constituting the base to an innovation

Seeing the static story structure looping through the scaling and scoping of opening up alternative outcomes, and paths, as a means of making it dynamic, the process of merging the story and gameplay had turned into an "innovation".

As the cognitive exploration space is based on the convention of a static story structure, it risks being conveyed and conveyed over again. Considering those narrative possibilities are consumable, if each new conveyance of the static and scripted story structure is patented due to its surprising effect on the business, we will ultimately run out of possibilities.

Given that the narrative is more than a structure, constituting the core to how we organize our thoughts, learn, understand, communicate, engage and motivate others and ourselves, I intend to illuminate the narrative as a dynamic element beyond conventions.

To understand how to scale and scope the patent from a cognitive-friendly perspective, I will go straight to the bottom of the core from which we formulate our thoughts into meanings.

Through a cognitive approach to the game- and narrative design of engaging and motivating experiences, I will explain how we navigate as sense- and meaning-makers in the creation of meanings (narratives) and round up by testing the patent's legal aspects.

So hang in there and have a sip of water.

I have scrupulous respect as a hybrid for our capacity to think and learn by listening to the gut connecting to our sense- and meaning-making. But since we are extremely fast at sense-making, it can be tricky conceiving the differences between making sense and making meanings when navigating through the design space.

We rarely hear creators talking about the quiet moments of sense-making when formulating the thoughts. What we hear are the results from the sense-making, i.e., the meanings. Intuitively we are well aware of this as otherwise, we wouldn't have goals directing our thoughts. With the help of the goal, we can turn our sense-making into the internal activity of meaning-making to generate a result - a meaning. So sense-making without a clear goal usually creates fuzziness.

Since communication and understanding are the central pillars to reach the desired outcome, when we return with our results from making sense of the parts forming a whole, we instinctively know the conclusions need to fit with others' solutions. This is why a shared goal is preferable to avoid endless meetings trying to get everyone on the same track during the process.

See the series Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings where I closely describe why the desired goal of what the player should experience or feel needs to be shared across disciplines and should be superior to other goals.

When I navigate a client's sense- and meaning-making, I'm ensuring the intrinsic motivating mode and the desired goal of what the player shall experience and feel are intact. Simply put, I'm keeping an eye on the continuity and consistency of how the narrative principles of logic, time, and space connect into a comprehensive network.

As my sense- and meaning making is also moving at the same speed as others' (at least I hope so), I'm very observant of the cognitive concept called control.

When causal, spatial, and temporal links don't make sense, control enables us to sense an emotional reaction of an "unsatisfying feeling" until the problem is solved, indicating the control is restored. Control also signals to us when something unexpected happens as well as when the parts corresponding to the goal fall into place. Control simply provides us with signals regarding our understanding. This is why I often say that we like to understand how the causal, spatial, and temporal links make sense, which constitutes the prior core to the motivating forces you employ to engage the player's meaning-making.

Our sense-and meaning-making assimilates causal patterns provided by the static story structures and blueprint of the Hero's Journey in the fast-paced industry. The causal patterns I refer to are the conflicts (contrasts) and turning-points associated with the dramatic story structure (see Putting into play on pacing). We conceive control from the familiarity with the narrative pattern constituting how the workflows and roles are organized. This explains why we like to know that someone who works with the narrative does what they are expected to do and vice versa. Control also makes us maintain conventions concerning the narrative and the game because we get used to them.

Simply expressed, control explains how cognitive forces dynamically turn unfamiliar elements into familiar concepts, opening up for creators to surprise.

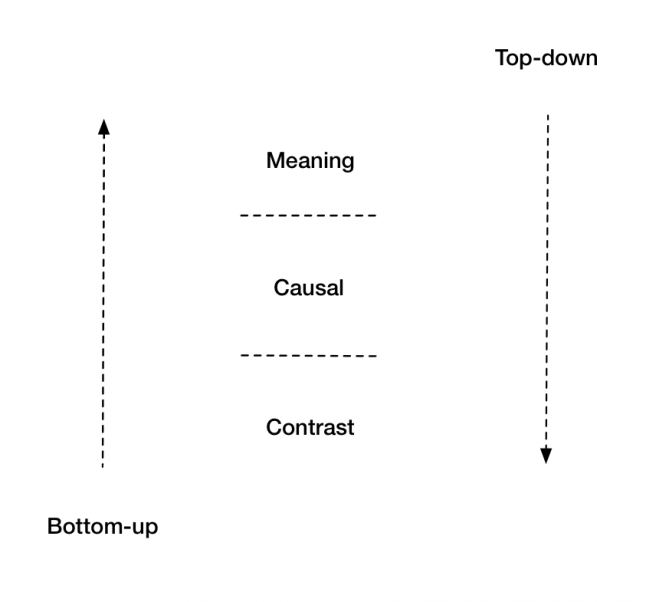

In an earlier episode of Panic Mode, Shelby and Aidan explain the terms bottom-up and top-down. The terms allude to a thinking strategy helping creators to navigate through space as meaning-makers. This strategy has evolved from the design of digital media.

Top-down

-------------

Bottom-up

To have a bottom-up perspective as a game creator commonly means you build around a core mechanic to achieve the desired outcome of gameplay. A top-down view refers to when you break down a large set of information to formulate the gameplay's mechanics and systems.

Due to the conventions of the narrative, the dramatic story structure is commonly considered an extensive set of information that you break down to pick out the engaging and motivating forces forming the core gameplay.

Story

-----------

Gameplay

Regarding the patent of the Nemesis system’s methods creating a gameplay pattern. It is easier to understand from a bottom-up perspective why game creators feel limited to utilize mechanics and systems as the possibilities to engage and motivate reside in the medium’s technique.

Why the story from a top-down perspective is not considered as a part of the patent depends a lot on how the well-known theme of Tolkien’s world has a low surprising effect on us because its objects, world, and actions are anticipated familiar elements encouraging exploration of new experiences that propels the gameplay.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Anticipated familiar elements of Tolkien's world encourage exploration

Anticipated familiar elements of Tolkien's world encourage exploration

However, what’s exciting from a cognitive perspective is how our sense of breaking down the narrative from a top-down view is actually very accurate.

During the design process, we generate a constant flow of meanings while navigating through the design space. We inevitably end up with an extensive set of information as sense- and meaning-makers when presenting results/meanings. In this way, we are continuously occupied by breaking down meanings so we can understand how parts meet the goal.

From a hybrid’s cognitive friendly perspective on the construction of narratives, meanings constitute "the top". The meaning could be anything from a vision, phrase, or sentence in which a causal network of objects, worlds, and actions containing the engaging and motivating forces.

Meaning

--------------

Causal

But we aren't at the bottom yet.

First I want to show how the thinking strategies reveal something exciting about the general expectations on the narrative's appearance and behavior.

It surprises us.

When listening to game creator's discussions about the thinking strategies, you can hear the contrasting conventions regarding the game and narrative and how the narrative is expected to be a top-down breakdown of a static story structure. When someone describes how the story "just came to them" during the process, amazement is often expressed.

It is the sense- and meaning-maker appearing from "the bottom” that surprises us.

I've shared examples in earlier posts of creators describing how they proceed from a bottom-up perspective. Fumito Ueda is one of them, whose description of his thinking has been beneficial when I've explained how our meaning-making works (see the series Putting into play). Ueda is also someone who generates an almost magical impact of amazement, which I find very interesting.

This time, I recommend listening to another example of a creators' exploration of narrative possibilities from a bottom-up perspective. It is a GDC talk called "Design by Chaos," which I linked at the end of the last chapter on pacing where the game programmer Seth Coster explicitly describes a bottom-up design, expressing a surprise how the story came later.

Why Coster defines the design process from a bottom-up perspective as "chaos" doesn't depend on an unconsciousness of how our thinking works. On the contrary, with a shared goal and a gut helping us control the navigation, we manage very well, altering top-down and bottom-up perspectives, breaking down meanings.

The GDC title, "Design by Chaos," actually shows how Coster intuitively understands the convention about the static and scripted narrative constitutes a base to engage and surprise the audience. In this case, the audience is game creators, whose conceptions and expectations on the narrative are utilized by Coster, who knows how to surprise a community that collectively subverts expectations on the narrative's behavior.

To understand the core behind the surprise, we need to explore the narrative possibilities beyond conventions by navigating to the very, very, very bottom of the minimum data triggering our sense- and meaning making.

If you have read the earlier chapters on pacing, it won't surprise you to see how the contrast constitutes the core to the engaging and motivating forces.

-------------

Contrast

Contrast is the minimum data (code) of a narrative that triggers our attention. Adding a causal network (cause and effect) to the contrasts enables you to set the motivating core that engages the player's meaning-making.

Cause and effect

-------------------------

Contrast

There is an infinite number of narrative possibilities residing in the combinations of contrasts waiting to be explored and conveyed by the game medium's technique and style. In the chapters on pacing and balancing in Putting into play, I explain how you utilize contrasts and cause and effect to create a motivating core loop.

However, earlier I mentioned how we rarely hear creators' sense- and meaning-making, only the meanings.

You can.

If listening carefully to game creators descriptions (meanings) of the engaging and motivating forces driving their games, you can hear how it revolves around contrasts, such as: good/evil, peace/war, mercy/vengeance, hope/despair, faith/distrust, modesty/arrogance, domination/subordination, victory/defeat, enemy/friend, or static/dynamic, as in Coster's talk.

Through contrasts, you connect the narrative as a meaning-making mechanism in how you convey causal, spatial, and temporal links through the medium's technique and style from a bottom-up perspective.

When making sense of the contrasts and how the causal network connects the parts from a bottom-up perspective you can recognize the similarities between our sense-making and the computer's conditional expressions: if, then, and else. For example, when you create flowcharts, it clearly shows how your sense- and meaning-making assimilate the computer's behavior.

In summary, I will depict the meaning-makers navigator of how you are altering between breaking down meanings from a top-down perspective and picking up contrasts from a bottom-up view, as follows:

A meaning-makers navigator

If you would like to try the cognitive friendly navigator,

Notice how when you handle the contrasts how the sense-maker inside you ask: if, then, or, else.

When having a clear and shared goal, you will hear the meaning-maker inside you assimilating causal contrasts between elements asking: who, where, when, what, and how.

When dealing with the meaning, we commonly ask why, leading the navigation back to the "bottom" or the "middle" to find the answer of how the parts form a whole.

The meaning-makers navigator captures how we weave dynamic (emergent) patterns when making the parts meet the desired outcome of what the player should experience or feel. Based on an intrinsic motivation mode, the navigator constitutes the base to how you form a gameplay loop from a bottom-up perspective and assembling systems and mechanics.

From a meaning-makers perspective, the narrative is more than a static story structure. It constitutes the core of how we formulate and organize our thoughts and forming meanings, turning us all into narrative constructors, authors of results directed by internal and external goals.

As long as the narrative is considered a static story structure and surprises us when its scripted and embedded structures are challenged, unconsciously, we kind of are the Nemesis of narrative by narrowing our space from exploring narrative possibilities beyond conventions.

The Nemesis system's patent illuminates an inconsistency in the game industry's ecological system regarding creators' exploration of narrative possibilities as meaning-makers. Considering the surprising effect of a narrative possibility is consumed. Imagine each time someone challenges the static and scripted story structure, how many "unexpected spaces" will there be left to explore?

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

From a top-down perspective, the graph shows how we build genres as meaning-makers. At the bottom, the causal contrast of the unexpected is waiting for the next surprise to be created.

A genre is a categorization encompassing a specific element generated by narrative possibilities, where sometimes a creator's drive to create something new can name a generation of new versions, such as Tolkien's work.

Based on conceptions, the narrative has become a genre of its own throughout the years, competing in its own category and winning awards in the form of the year's best game narrative. The graph outlines how the narrative genre has evolved from conventions and how the Nemesis system's gameplay pattern is embedded in the narrative genre.

The patent is merely a narrative construction based on preconceptions (meanings) regarding the narrative's appearance, risking the game business painting itself into a corner. Legal processes within the narrative and cognitive domain can become lengthy, random, and arbitrary, building complicated and fuzzy precedents.

Navigating legal, market, and business workers in the narrative domain shows how the ecological goal within entertainment is sometimes not shared, explaining why many game creators are currently occupied with making sense of the Nemesis system's patent to restore control.

However, coming to a conclusion is problematic as it involves a new context's hierarchy, system, and rules, preventing narrative possibilities from evolving - unless you can buy a path - a so-called license - to join the ecological vehicle. In this case, due to the pattern being a method, the license is like a game developer's microtransaction to make the engaging and motivating forces propel.

Since the patent concerns the merging between the "screenwork" and "data work," it seems from a hybrid's perspective as if one would need a license to convey the following elements:

A combat between two contrasting objects,

the objects remember who is the ally or the enemy,

who to show mercy or vengeance, and

where objects have the hierarchy of an army displaying its memory of the player's actions over time by promoting or demoting soldier-objects (non-player characters).

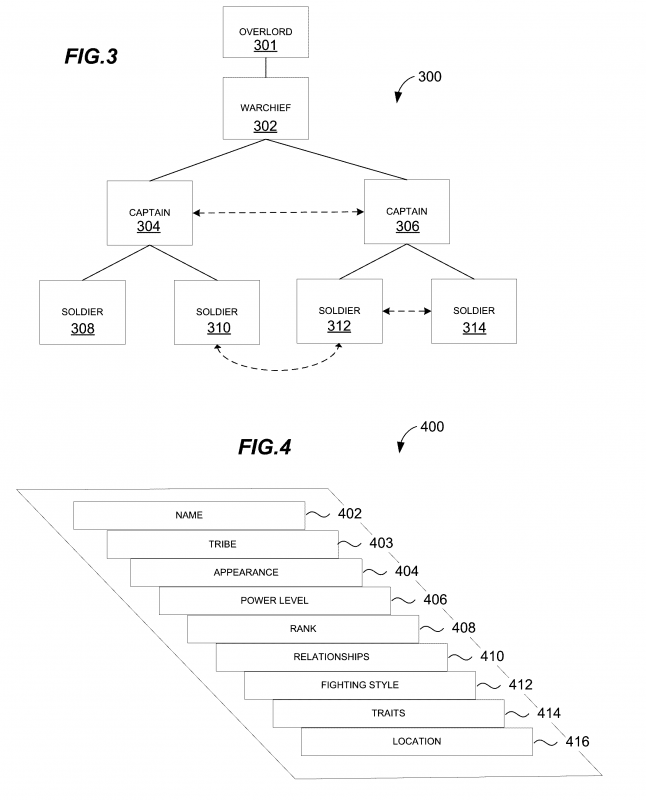

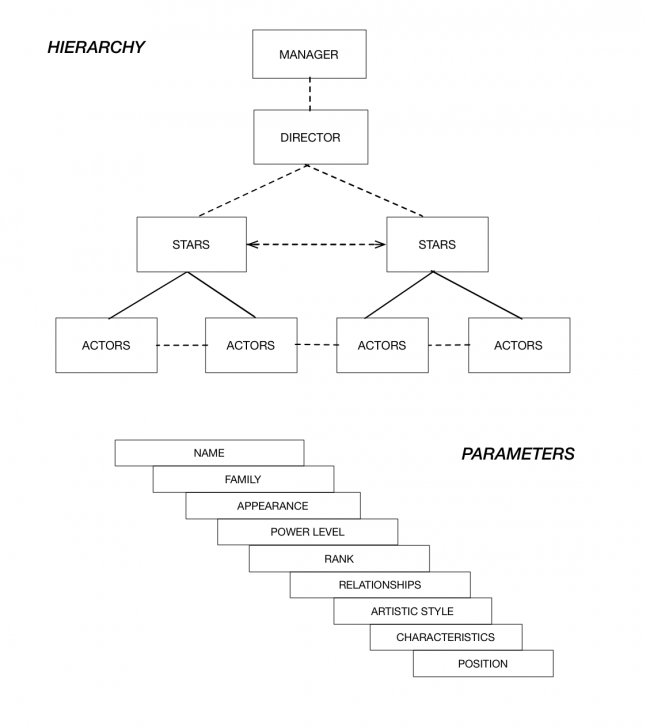

Ex from patent US20160279522A1 showing hierarchies and parameters of objects.

To test the legal aspect of the patent within the narrative domain I will round off by creating a three-step-evolvement of narrative possibilities and utilize the causal contrasts to change the objects, world, and actions.

The steps are followed by an open question on how to consider the concept’s novelty (surprising effect) in regard to the narrative, gameplay, or both.

Starting with the hierarchies and parameters above, I’m suggesting the following changes:

Let's make the combat into a competition.

Let the objects remember who has talent or not,

who to flatter or not.

Let the player-character be a part of a theatre troupe's internal hierarchy, which objects remember the player's actions as an actor over time by promoting or demoting actor objects.

Narrative possibility showing hierarchies and parameters of actor-objects

Based on competition between actor-objects to manage the theater troupe's stars and actors, the objects remember outcomes of earlier competitions such as if the player showed talent, loyalty, or disgraced someone in the troupe.

As the example isn't based on the familiar elements of Tolkien's world, would the concept pass without a license as it is a "new narrative" embedded in the narrative genre utilizing the medium's technique and style to surprise?

Let's add something new to the theater-troupe concept by turning all actor-objects into orcs, including the player-character who is a part of the troupe.

To make sense of the orcs' appearance and behavior, we can create a causal contrast and nuance the environment.

Tired of all the wars in Middle-Earth, the orcs have left for a more peaceful world, finding the circus to be a great place to blend into a new world where no one expects circus artists to look anything else but amazingly monstrous.

To meet the desired outcome of a dynamic and motivating core, I will add a goal (need/motive) to move the circus after a specific time to avoid being revealed as orcs pretending to be circus stars (like the same drive forcing the gang in Red Dead Redemption 2 abandon their camps to escape the Pinkertons).

In addition to the need for moving I will add a parameter by creating causal contrast to propel the player’s meaning-making in the position of being an actor.

Due to vanity among the superstars who love the limelight, a movement saving the circus can only be done from the position of being the manager, which triggers the player’s meaning-making finding strategies to make it to the top of the hierarchy (player’s call).

Will the circus, driven by orcs from Middle-Earth, be considered as a new take on Tolkien’s world within the story/narrative genre? Or will it require a license based on the dynamic and procedural modeling of the actor-objects behavior over time?

Let's break the linear plotline leading to an ending of alternative outcomes based on the player's goal reaching the top of the hierarchy.

When the circus is moved, the player needs to make it back to the actor-position so the star-orcs-objects will once again stand in the spotlight and no longer desire returning to the old place.

Now we have a causal escaping-moving-establishing-loop affecting player's meaning-making and behavior of strategically going from actor to manager and back to the actor-position, and so on.

Will the change of the end of the plotline's interaction with the hierarchy's final end state by looping the player's causal behavior of changing position be considered a new gameplay pattern as it doesn't fit with categories of alternative outcomes of plotlines determining the narrative genre?

The more we utilize opportunities based on conventions, the more robust they’ll get. Therefore my personal thoughts feel pretty irrelevant as collective agreements are required to change traditions. Nevertheless, I will say a few words before I return to my evolutionary state of mode.

The patent of the Nemesis pattern will expire in 2036. Until then, I hope the conveyance of cognitive and narrative forces through the game medium's technique and style will be understood from the perspective of human learning's interaction with the computer's learning - a field in which cognitive patterns should be untouchable.

Even if the ecological system of entertainment has its own agenda. Regarding the digital medium, I consider science has a responsibility to bridge gaps between fields.

Contrasts from a cognitive and narrative perspective have a powerful impact on our attention, engagement, and memory. Contrasts, in reality, have the same effect as in fiction. Classical stories with a hero are driven by a causal contrast, giving fuel to engage others attending the hero who becomes the protector. The versus between the narrative and the game created twenty years ago by game study scholars (also called "ludologists") worked as fuel to a conflict where some made themselves into the game's protectors at the cost of the narrative understanding. The protectors' arguments are now a part of game studies, which each new student needs to pass. In this way, conflicting contrasts maintain the border between the story/narrative and the game.

I'm okay with being a hybrid dealing within the expectation interface between the screen work and data work. But due to the patent being a cognitive pattern, an unpleasant fact is that I don't feel comfortable sharing methods and patterns when I'm not sure where the ecological system of being a creator is heading.

However, I'm glad I could finally give an answer to Shelby and Aidan and provide an extension to the episode on Cognitive narrative design. Thanks to them and all the other curious explorers, I'm finding it meaningful to share my thoughts and methods.

One more thing. If you happened to come this far and thought the narrative wasn't your job, I would love to hear your thoughts.

Thank you for listening to a hybrid's concerns.

Take care and stay curious!

Katarina

Panic Mode, insider’s take on game design by Shelby Carleton and Aidan Herron

Panic Mode, Episode 2 on Top-down vs. Bottom-up Game Design

Panic Mode, Episode 63 on Cognitive narrative design

The United States Patent and Trademark Office

Gameindustry.biz Podcast, "One patent to rule them all"

Game Maker's Toolkit by Mark Brown on the Nemesis system

Examples of news coverages on the patent IGN, Eurogamer, Geekwire

Rhianna Pratchett on patching the narrative (story) to mechanics and systems

Molly Maloney and Eric Stirpe on writing and narrative design.

Edwin McRae on Procedural Narrative: The Future of Video Games

Pete Ellis on Subverting players' expectations in The Last of Us Part II

Seth Coster "Design by chaos" on designing from a bottom-up perspective

Chris Crawford's Dragon Speech

Middle-Earth: Shadow of War Monolith /Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment

Research portal, Peter Gärdenfors, Senior Professor at Lund’s University, Sweden.

Metsämuuronen J and Räsänen P (2018) Cognitive–Linguistic and Constructivist Mnemonic Triggers in Teaching Based on Jerome Bruner’s Thinking. Front. Psychol. 9:2543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02543

About cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner (narrative pioneer), The Psychology of What Makes a Great Story by Maria Popova.

The 1999 ludology manifest to game studies

Conditional computer programming

Emergent structures and behaviors

Hands-on guide: Predicting players´ thinking

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design.

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

Part 5, Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings

Part 6, Putting into play - On organizing engaging and dynamic forces

Part 7, Putting into play - The Hidden Art of Pacing 1 (3)

Part 8, Putting into play - The Hidden Art of Pacing 2 (3)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like