Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

In this piece, I share my thoughts and experiences on what it means to make videogames for a living having spoken to developers over the past 7 years and where people still have trouble grasping about the practice.

Much like Hollywood, the video game industry has regularly demonstrated that it loves winners. And, as with Hollywood, you’re often only as notable at your last hit. At the same time, it feels like new studios and student developers struggling to make their first successful game, are emerging on a near-daily basis. While it’s true that we all love a good success story, it’s equally true that many folks both within and outside the industry fail to understand why a given title has achieved significant success.

I believe this lack of understanding derives from a kind of romanticism surrounding game development. This is especially true if we only think about games as works of art that aren’t subject to very specific constraints and practical considerations. My argument here is that we should demystify this view, so that we can have more useful conversations about game design and why certain projects become successful (or not).

Let me leave you with no misunderstanding about my own point of view: video games are definitely an art. In my opinion, this isn’t debatable; we’re well past this point now. Like any art form, game creation is typically driven by great passion—it’s this passion which has fuelled many thousands of people to embark on their own development projects.

Every developer has their own game they want to make and a story around how they broke into the game industry. I’ve spoken to two developers who quite literally lived in a treehouse for years in order to make their first game. There was the creator who started a project due to a near-death experience. There was even one group who covertly built their game at school when nobody was around.

While it’s true that there are now many game development courses available at a tertiary level around the world, there’s no formal “game developer’s license”. To put it another way, there’s no formal process one must go through to become a game developer; if you’re building a game, you’re a game developer.

The Alumni wall at DigiPen. DigiPen is arguably the world’s most well-known gaming-centric college.

What’s interesting, though, is that many of these aforementioned courses tend to focus some combination of art and coding (perhaps with some marketing and “productisation” included). One thing that seems to be absent from many courses is, for lack of a better term, a science of game design. One piece of feedback I often get from game developers is that there’s some real resistance around setting any kind of standards for design or implementation—the implication being that this will stifle the creative process. My argument, though, is that no matter how creative, original, or amazing a game’s concept might be, the very best games are built upon a “science of game design”.

What do I mean by “science of game design”? I’m referring to fundamental concepts that contribute to the effectiveness of a game’s design — concepts that are not subject to an individual’s taste of opinion, at least, not as much as something like art or music. No, these are concepts that are more logical in nature and are based on sound, testable hypotheses.

If my argument so far is sounding unfamiliar, it could be because gaming media in general doesn’t seem to discuss—or explore—the science of game design. There’s an enormous amount of video game-related content out there, and there are a million valid ways to discuss and enjoy video games. But when it comes to discussing game design as a science, I’ve found it most important to engage with designers and developers themselves.

In the last seven years, I’ve interviewed more than 400 developers and industry folks. I’ve spoken to people like Fred Ford, Paul Richie, Edmund McMillen, Zach Barth, and other developers who “made it” in the game industry. Conversely, I’ve also interviewed many developers who spent years building games only to have them crash and burn commercially; many of these were incredible, innovative games that most gamers have never heard of (and certainly never played). I never cease to feel great sadness at these “failures”, especially after talking to their creators.

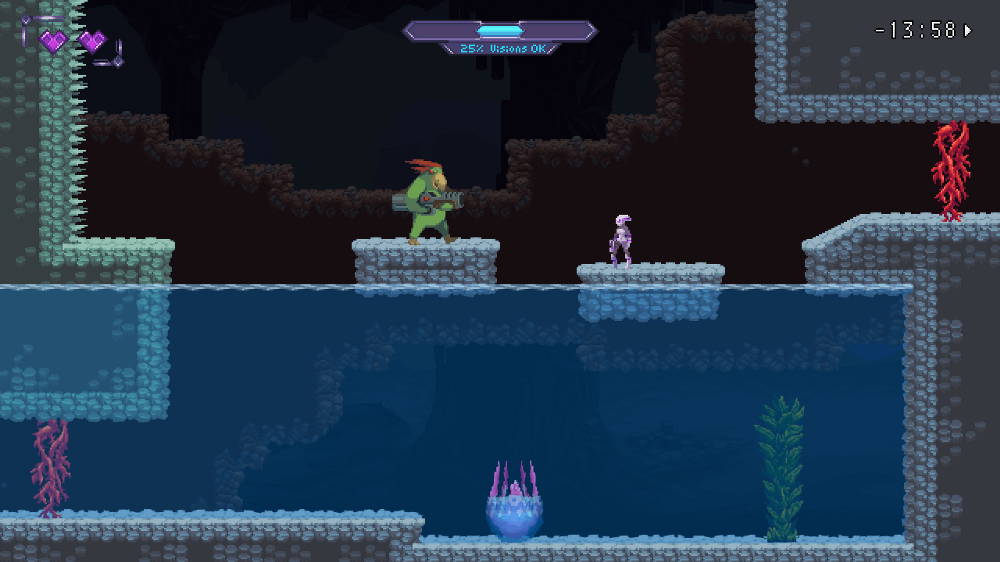

The remarkably good—but underrated—Vision Soft Reset. Check out our review.

Actually, one game that comes to mind within this category of “brilliant failures” is Vision Soft Reset; I interviewed the developer earlier this year. This is a game that I’d easily consider one of the best games I’ve played so far this year. Sadly, it has less than ten Steam reviews as of the time of writing. Other developers have suffered far greater fates—even to the point of a commercial failure ultimately leading to the bank repossessing their assets.

It may sound like I’m painting a grim picture. And I suppose I am in one way: I’m attempting to highlight the importance of understanding the science of game design in an effort to more effectively grasp why particular games are successful or not. I see a lot of confusion about this within the gaming media, but it can also exist within the walls of even the largest and most established development studios.

Anthem’s development was fuelled by the vague promise of “BioWare Magic”.

Case in point: the enormous failure of BioWare’s Anthem. It’s certainly true that many in the media—including YouTube influencers—were able to articulate clear reasons why the game didn’t live up to most’s expectations. But it took an in-depth investigate piece by Kotaku’s Jason Scherier to surface the myth that existed within BioWare itself that the studio possessed something called “BioWare Magic”—a secret sauce that somehow allowed the company to succeed, perhaps without truly understanding the design principles that underpinned their own popular franchises. Some fans have adopted a similar view around companies like Nintendo, Blizzard, and Valve: that they just possess a special DNA that allows them to effortlessly spin up hit after hit.

To be fair, at least some of the misconception among fans—and even games journalists, occasionally—owes to a lack of transparency when it comes to the game development process itself. Unless you talk to developers (or closely follow development as a game is being produced), you’ll only see a final product without the long trail of iteration, arguments, debates, and sometimes the masses of content on the cutting-room floor.

In this context, I’m sure that there were plenty of people both within and outside BioWare who genuinely believed that the company would never make a flop, and therefore, Anthem came as a complete surprise.

This genuine lack of understanding surrounding the science of game design and the factors that underpin success can extend throughout the industry to smaller studios too—“me too” games are a perfect example of this. These are titles that slavishly mimic more successful games in an effort to ride on their coattails; but often these attempts to duplicate success are based on fundamental misunderstandings about the original property.

I know what you’re thinking. “You’re so smart, why don’t you tell us what makes a successful game!” Okay, fair point. It’s worth saying at the outset that any attempt to explain what makes a “good” game is, by definition, going to vary based on the kind of game being developed.

That said, there are some general rules of thumb I’ve observed over time, especially as a result of interviewing so many developers and dissecting their work. In no particular order, here they are.

Outside the echo chamber:

It’s very tempting to design the exact game you would like to play. And although that can be a valid choice (especially if there exists a large audience who has similar tastes to you), it’s worth considering the potential market for your game. What sort of players are you going to target? If they are fans of a particular genre, what is it about that genre they gravitate to (more on that in the next point)?

Look for consistency within a genre:

This is perhaps more a prompt for you rather than a direct answer. Highly successful titles also generally happen to be great from a game design perspective. A good starting point, though, is to take a group of highly successful games within a genre and consider which design elements are consistent across these games? Of course, it’s valuable to stand out within a genre as well—but not to the point where the experience is highly confusing or unintuitive.

Understanding the appeal of your design:

Think about your own project. What are the key factors that you expect to be appealing to players? Once you have defined the unique appeal factors, ensure that players can easily figure them out. Many games—especially indie titles—are unique and contain special appeal factors of their own. But where a lot of games fall down is that they fail to “onboard” players such that they can easily see these factors; the best games don’t take long to get players invested in them, and they rapidly build on that early momentum.

Polish and attention to detail go a long way:

This may sound obvious, but it’s so very important. Even the best games can be dragged down when they are full of bugs that get in the player’s way, or if they feature a user interface that is difficult to understand; always make sure to iron out as many pain points as possible in your design.

Test early, test often.

Test, iterate, and test some more:

Okay, this is a bonus point added by James. You can adhere to all the best design principles, but these are ultimately meaningless unless you regularly have players going hands-on with your game. More than anything, this is the key to success that so many developers underrate. Even giants like Nintendo were pioneering player testing before a formal “user testing” discipline had been invented. Player testing will help you to quickly uncover points of friction in your design, which will then enable you to smooth out those bumps and deliver a more enjoyable experience.

What we’re describing here isn’t a secret; it’s really the bare minimum when it comes to developing a great video game.

But there’s another important component that helps to drive success, and it goes well beyond building a great game.

This is another topic that really deserves its own separate discussion, but it is unfortunately an area of great importance. And based on my own experience with several great indie titles, it’s clear that lack of effective marketing can ensure an awesome game is never introduced to its rightful audience.

When it comes to marketing, I defer to Chris Bourassa and Tyler Sigman of Redhook Studios, creators of Darkest Dungeon. Here’s a game that could best be described as the poster child of indie game success. The team went from a successful Kickstarter right through to porting the game to multiple platforms. Now, Redhook Studios are widely known, and are busy working on a much-anticipated sequel.

Depending on who you are, you may have heard of Darkest Dungeon after it was ported to consoles and had already become a major success. But you may have heard about the game during its early access days, or perhaps even way back before the Kickstarter. This is simply because the team were engaged in marketing activities—actively reaching out to people—more than six months prior to launching the Kickstarter.

In retrospect, it might be assumed that the developers simply made a great game and everything else just fell into place. But it’s easy to ignore the fact that the developers invested significant time into communication very early in development.

The fundamental lesson is simple: success rarely comes through sheer luck or accident. When you look more closely at games that appear to be sudden, overnight hits, you’ll typically find that enormous, sustained effort is the underlying factor that really matters.

Perhaps even more importantly, it’s unwise to think of marketing as either a) “selling out” or b) someone else’s problem that only arises when the game is ready to ship. Marketing is an opportunity for you to champion your creation, and communicate what makes it special to the outside world. Leaning into it early, and making it part of the overall process, is vitally important.

So far, there has been a common theme underpinning my argument: the development team behind the game is ultimately responsible for its success. But the painful catch is that this isn’t always a given. Game development can be a scary—and risky—business because you might do everything right within your power (you had a great idea, you did effective marketing, you have a fanbase, you understand what it takes to make a video game), and you may still fail despite all that.

Further, past success doesn’t guarantee future success. The hallmark of a successful designer is that they don’t simply have one big hit, but that they are able to maintain relatively consistent success with multiple titles over a period of time.

(Although I agree this is largely true, I think the idea of “games as a platform” has shaken that up a little—some developers, like Mojang, might be considered a “one-hit wonder”, but they’ve managed to successfully take that one hit and build it into a much larger amorphous property that continually expands with ongoing iteration. Ed.)

One of the most salient examples I witnessed was Arcen Games, who saw enormous success with AI Wars—and then almost went out of business. I’ve spoken to Chris Park on multiple occasions, and he was frank about the mistakes he made in terms of game development, and the need to quickly adapt to keep his studio afloat. You can read Chris Park’s own account, too; it’s a fascinating and insightful story.

Arcen Games’ AI Wars.

There have, unfortunately, been plenty of developers who have had a major hit and then failed to maintain the momentum. This is why I tend to judge developers by their entire body of work, and not just their “best” game. If you want a depressing activity to really underscore this point, I recommend looking at your favorite indie games and see if the developers behind them are still making games, or if the original studio still exists.

Of course, this phenomenon isn’t exclusive to the indie space—it also affects the triple-A world as well. We’ve seen it happen with BioWare and Anthem, as well as Visceral Studios and Dead Space. Even a major name in the industry can fail for any number of reasons. The difference, of course, is that triple-A studios generally have more resources at their disposal; they’re often (but not always) able to safely absorb a horrific crash landing, where such disasters can mean outright obliteration for smaller developers.

The video game industry is now more than 30 years old. And yet, I believe many people discount or underrate the massive work—and risk—that goes into making games.

As discussed in this article, there are many things that contribute to a game’s success that are not under the developer’s immediate control. However, so much is under their control, and there are so many important elements that I believe require greater attention at a professional level—whether it involves the media, industry associations, or even the educational sector. Major topics like programming and aesthetics are widely—and effectively—discussed across the board. Marketing and production is increasingly being covered within the industry association and educational spheres, but a science of game design still represents a glaring gap in our collective professional understanding of the medium.

In the same way that colleges around the world treat game development as an accepted profession, we now need to treat game design as a respected and professional craft.

Be sure to join the Game-Wisdom Discord channel if you like my work and want to talk about game design.

Media credits: Instabug, NY Film Academy, Game Marketing Genie. This was originally featured on Super Jump Magazine and was given permission to be reposted here.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like