Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

As we reach the 30-year anniversary of the title that made Shigeru Miyamoto a superstar developer, a complicated tale of secret development contracts and protracted legal battles emerges from the ether.

[As we reach the 30-year anniversary of the title that made Shigeru Miyamoto a superstar developer, a complicated tale of secret development contracts and protracted legal battles emerges from the ether.]

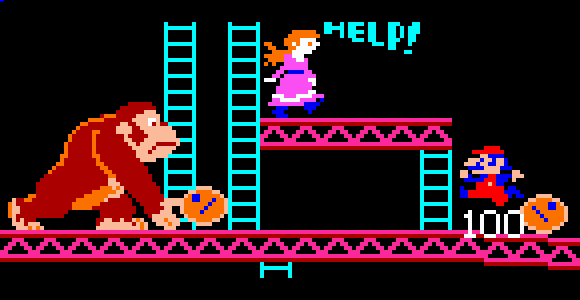

Donkey Kong is perhaps the greatest outsider game of all time. It broke all the rules because its creator, the now-legendary Shigeru Miyamoto, didn't know them to begin with. It not only launched the career of gaming's most celebrated creative mind, it gave birth to the jump-and-run platform genre as we know it, and established Nintendo as perhaps the industry's longest standing superpower.

Thirty years later, Donkey Kong remains one of gaming's most recognizable icons, and still much of its story is untold. Most accounts of its development treat Miyamoto as if he was the only man in the room; that his sketches, ideas, and sprites were brought to life either by magic or some worker bees too unimportant to even mention. For many years, the question of who developed Donkey Kong went unanswered because it was seldom even asked.

Back before credit rolls were a common part of video games, developers used to find other ways to sign their work, usually in the default high score tables, but sometimes with messages or initials embedded in the ROM itself. These are sometimes the only clues left to help connect these games to their authors.

A scan of Donkey Kong's ROM proves to have a more revealing message than most:

CONGRATULATION !IF YOU ANALYSE DIFFICULT THIS PROGRAM,WE WOULD TEACH YOU.*****TEL.TOKYO-JAPAN 044(244)2151 EXTENTION 304 SYSTEM DESIGN IKEGAMI CO. LIM.

Ikegami Co. Ltd., also known as Ikegami Tsushinki, is an engineering firm still operating today, and seldom associated with video game development. But back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was one of the first "shadow developers" in the Japanese market -- contractors like the famous TOSE that would develop games silently, without credit.

Not only was this hidden message found in Donkey Kong, but in other 1980s classics like Zaxxon and Congo Bongo, both released under Sega's name. Ikegami was more than just a group of hired coders; it was a full development team capable of repeat success, and unlike other shadow developers, it owned the rights to games it developed, placing Donkey Kong at the center of a bitter copyright dispute.

Shigeru Miyamoto first came to Nintendo, a quickly growing toy manufacturer, in 1977. It seemed like a dream job for the artist/engineer, still fresh out of college, who had joined the company in the hopes of designing toys. But Nintendo was just beginning to explore a new medium, the burgeoning market of coin-operated video games, and Miyamoto's dreams were deferred. Nintendo's president, Hiroshi Yamauchi, assigned the young designer to create the cabinet and promotional art for its new video games, Sheriff, Space Firebird, and Radar Scope.

Unlike Nintendo's previous arcade machines -- largely electromechanical amusements -- these arcade machines were programmable video games with relatively cutting-edge hardware, a major step toward competing with the likes of Taito, which had changed the face of arcades with the release of Space Invaders.

Unlike Nintendo's previous arcade machines -- largely electromechanical amusements -- these arcade machines were programmable video games with relatively cutting-edge hardware, a major step toward competing with the likes of Taito, which had changed the face of arcades with the release of Space Invaders.

Nintendo's management knew what it had to do to compete, but the company's modest engineering department had not yet become a video game development studio. Nintendo turned to Ikegami Tsushinki, which agreed to develop games under Nintendo's name, as well as engineer and manufacture the hardware they would run on. Nintendo made the cabinets itself and handled all the marketing. It seemed like a fair arrangement.

Either because of their eye-catching cab art or their clever gameplay, Sheriff and Radar Scope were successful in Japan, but Nintendo's rivals like Taito and Namco were making a killing in the American market, and Nintendo wanted a piece of the action. Yamauchi tasked his son-in-law, Minoru Arakawa, with establishing an American base of operations, and their first order of business was to bring Radar Scope to the U.S. market.

Because Nintendo could not make their own Radar Scope hardware to match demand, they were forced to order units from Ikegami ahead of time. Anticipating America would greet the game as warmly as its native Japan, Nintendo ordered 3,000 units from Ikegami, and shipped them to Nintendo's American distribution facility in Washington.

Alas, Radar Scope was not a hit in America. In fact, it sold only 1,000 units, leaving 2,000 arcade machines with very expensive hardware sitting in Nintendo's warehouse. The implications were potentially devastating. Nintendo could either give up, and face financial ruin, or it could develop a conversion kit that would turn those cabinets into something marketable. Arakawa begged his father-in-law to pursue the latter course of action.

Nintendo, lean on experienced game developers, placed Miyamoto in charge of the project. Miyamoto had never designed a game before, but he had been doodling ideas for characters even as he worked on Nintendo's cabinets. Yamauchi assured him his lack of technical skills would not be a problem. Miyamoto would simply give direction to the team at Ikegami Tsushinki, and it would develop the game according to his ideas. Gunpei Yokoi -- later known as the father of the Game Boy -- would further guide Miyamoto on technical and design concerns.

It was not only the first real game design Miyamoto had done, but the first time anyone at Nintendo had been deeply involved in the game design process. Placing an inexperienced designer in front of such an important project might seem like a risky move, but Miyamoto's unique perspective would prove to be his biggest asset. Miyamoto did not approach game design the way others did. Where most games at the time involved scenarios drawn from action movies -- shoot-outs, race cars, submarines, and intergalactic battles -- Miyamoto wanted his game to feel like a comic strip come to life.

Even the notion of discrete characters with individual personalities was fairly uncommon in arcade games at the time, but characters and story were fundamental to Miyamoto's vision.

Initially he had hoped to create a game based on Popeye and his perpetual battle with Bluto over his damsel in distress, Olive Oyl. Nintendo was unable to secure the license -- at least at that time -- so the designer superimposed the classic love triangle over a King Kong theme.

A lovestruck gorilla absconds to the top of a construction site with the prettiest girl he sees, and her carpenter boyfriend has to come to her aid. Just a picture of the scenario can tell the whole story through the din and distractions of a busy arcade.

Even Miyamoto's methods of communication mirrored the comic medium he was inspired by. Like Sonic the Hedgehog designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, he would draw pictures of scenarios on paper, each one a whimsical snapshot of how the game would feel. While jumping wasn't a new mechanic in games, Miyamoto envisioned a character that would have to jump over hazards, onto moving platforms, and across gaps in a way that had never been done before. The action was just plain fun, funny, and fit perfectly with the game's lighthearted tone.

The game the two companies created communicated quite a bit without the need for words. The decision to show the giant ape as he scaled the building's scaffolds, to show Pauline crying for help, and to show the gorilla's escape at the end of the level was a bold one at the time. Normally these things would just be implicit, but Miyamoto wanted to make sure the whole story, simple though it was, could be told on screen in a way that could be instantly grasped by players.

This also allowed for an innovative multi-stage design that boasted four very distinctive screens of action with unique challenges, without confusing the objectives. Pauline was still near the top of the screen crying for help, and Mario's goal was clear. That desire to see the new levels, rather than just repeating the same one over again would motivate players, especially the more causal, to drop more quarters into the game in a way that just competing for high score never could.

Yamauchi immediately recognized that Miyamoto's game could be the one to save Nintendo's sinking American operation. He asked the designer to give the game an English title that Americans could relate to. Of course, Miyamoto knew very little English, so when he tried to look up a word that would accurately convey his ape's stubbornness, he came up with the somewhat perplexing "Donkey Kong".

It didn't matter. The game arrived just in time to save Nintendo's American division. The situation was so dire that the company's landlord, Mario Segale, had been coming around demanding the late rent payments owed to him. Arakawa thought the mustachioed owner looked a bit like the hero of Miyamoto's game, so Jumpman was renamed to Mario in his honor.

While Donkey Kong was poised for launch, Nintendo's American arcade division was teetering on the brink. Resources were so tight that Nintendo of America's three employees had to convert all 2,000 Radar Scope units over to Donkey Kong by themselves. But once those units started making their ways into the darkened hallways of arcades around the country, Nintendo's only problem was where to get more.

That problem wasn't as straightforward as it sounds. Ikegami Tsushinki produced the initial shipment of boards, just as they had done for Radar Scope, but Donkey Kong was a huge hit and Nintendo needed more. Demand was so high in America that Arakawa began manufacturing new units in Nintendo of America's warehouse.

But Nintendo didn't actually own the manufacturing rights to Donkey Kong. Although their game was still a Nintendo product, and the characters, name, and brand all belonged to it, the development contract gave Ikegami Tsushinki the exclusive rights to manufacture and sell boards to Nintendo for ¥70,000 each. After the initial order of 8,000 units, Nintendo ceased to buy boards from Ikegami. Although the contract was unclear with regard to actual copyright of the program code -- still new territory for the law -- Ikegami was named as the sole supplier for Donkey Kong boards.

Nintendo didn't see it that way. Before long, Nintendo had manufactured about 80,000 additional units without Ikegami's involvement, burning the bridge with the company that had developed its biggest hit, and opening themselves up to a bitter legal battle that would drag on for almost a decade.

This also left Nintendo without a development team to follow up its smash hit. Nintendo wanted a sequel, but Ikegami was done with them. Soon after, Ikegami would go on to anonymously develop the innovative smash hits Zaxxon and Congo Bongo for Sega, contributing to the rise of one of Nintendo's biggest rivals. Ikegami Tsushinki was clearly an immensely talented team, but its terms were too restrictive for Nintendo's needs, and it needed to find a new partner.

Nintendo hired another contractor called Iwasaki Engineering to disassemble and reverse engineer Donkey Kong so that Nintendo could add new graphics, stages, and mechanics for a sequel. This time, the nature of the agreement was clear to both sides from the start, and would turn out to be a long and fruitful partnership. As Nintendo established its internal R&D, many members of Iwasaki would join its ranks. Before long, Nintendo was developing hit games completely on its own.

Shigeru Miyamoto's mind had been racing with more ideas since before he finished the original Donkey Kong, and his sequel came naturally. He wanted to show that the eponymous antagonist was more complex than just a big, mean ape, so he considered telling the story from Kong's perspective.

Of course, DK was simply too big to be a player character, and so Miyamoto made him a father, introducing a new hero, Junior, out to rescue his dad from the vindictive Mario.

Ladders gave way to vines and chains, and the barrels were replaced with nasty Snapjaws and birds. Donkey Kong Jr. was clever for a sequel released so soon after the original, with patterns that bore little resemblance to its predecessor.

The large amount of moving sprites was quite dazzling in 1982, and the climbing and reaching mechanics offered something fresh from the original. Once again four unique stages kept the gameplay varied and had players sinking in quarter after quarter to try to make it a little further.

But for all its very original ideas, Donkey Kong Jr. was still built on code reverse engineered from the original game -- code that was already the center of a copyright dispute. In 1983, Ikegami Tsushinki filed a ¥580 million copyright infringement suit (about $8.7 million adjusted for exchange rates and inflation) over both Donkey Kong and its sequel.

The legal battle dragged on for years, long after Ikegami left the game development business. In 1990 a court ruled that Nintendo did not have the rights to Donkey Kong's code, and the two companies settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. With the case settled and Ikegami long gone from the gaming business, little is said about Miyamoto's anonymous collaborators and the role they played in one of gaming's most important titles.

The squabbles surrounding the development of Nintendo's first international hits were barely a blip on the radar compared to the tremendous impact of the game itself. Donkey Kong and its sequel had effectively given birth to a new genre of side-view jumping games, with countless imitators -- some clever and some blatant -- appearing in America, Japan, and Europe, in arcades, on consoles, and on home computers. By 1983, folks in the West started calling these "platform games".

The squabbles surrounding the development of Nintendo's first international hits were barely a blip on the radar compared to the tremendous impact of the game itself. Donkey Kong and its sequel had effectively given birth to a new genre of side-view jumping games, with countless imitators -- some clever and some blatant -- appearing in America, Japan, and Europe, in arcades, on consoles, and on home computers. By 1983, folks in the West started calling these "platform games".

In 1982, Shigeru Miyamoto got to make his Popeye game, officially licensed and all, on brand new, more powerful hardware. Nintendo went on to develop a third game in the Donkey Kong series with an all-new protagonist, Stanley the Exterminator.

The third in the trilogy bore little resemblance to its predecessors, abandoning the platform mechanics in favor of an unconventional shooter motif that had Stanley pressuring DK into a beehive with his bug spray. It failed to take off like the earlier games did, and Donkey Kong was put on a long hiatus.

With an internal development team and a small stable of strong brands in place, the stage was set for Nintendo's most ambitious move yet. In 1983, Nintendo released its brand new Famicom console with three ports of Shigeru Miyamoto's arcade games: Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye.

While concessions were made for ROM size and resolution, the ports were simply much closer to the real arcade experience than any home system could deliver up to that point, paving the way for Nintendo's extended domination of the console market. By the time the NES would reach our shores, Nintendo was winding down their arcade development for good. In just a few short years, Nintendo had changed the gaming landscape.

Donkey Kong has continued to be one of Nintendo's most recognizable characters, albeit in a form that would be almost unrecognizable to gamers in 1981. But Kong's legacy is far greater than that. If you can't imagine a world without Super Mario Brothers, without the NES, and maybe even without Nintendo at all, then you can't imagine a world without Donkey Kong. Both as a remarkable piece of game design and a commercial breakthrough for the single most important gaming company in Japan, Donkey Kong changed the world, and 30 years later we're still feeling its effects.

Note: Special thanks to GDRI for their tireless research and Masumi Akagi for his book Sore wa “Pong” kara Hajimatta.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like