Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Where does the "social" fit in social games? Digital Chocolate lead social designer Aki Järvinen examines social concepts and social mechanics to explain what types of interactions these games embrace and eschew.

[Digital Chocolate's lead social designer Aki Järvinen analyzes the current state of social exchanges in Facebook games. He introduces concepts such as social presence, social graph, and social space to explain the kind of social interactions these games embrace, and fail to embrace. The feature presents work in progress from a book Järvinen is writing.]

Signals from the field seem to indicate that the "social" in social games is broken. For example, a GDC 2010 presentation Daniel James from online and social games developer Three Rings described the sociality of social games as something that equals passing notes under the door of a friend, instead of knocking on the door. Social games mainly work as distractions rather than playful social interactions.

Other developers have gone to the length of accusing social games for "hating" socialization, and in his critique of social games, Ian Bogost sees social games merely instrumentalizing social relationships into simple game resources, thus implying that more authentic forms of playful social interaction entail something different altogether.

In the summer 2010 issue of Casual Connect magazine, David Rohrl from Playdom gives away that there are particular elements that make games socially relevant, or more precisely, "make players feel like they're playing with their friends (even when they're not)" -- the final part is significant, as it implies that social game developers are practically in the craft of creating sets of smoke and mirror tricks in order to create illusions of social exchanges where there truly are none.

The story continues on the players' side as well. According to findings in the SoPlay research project, players mainly consider social games as single player games, which, despite putting their friends on display on the game, is "not the same" when compared to their conception of multiplayer games. It seems that players have hard time articulating what they are doing when they are interacting with their friends via a game on Facebook, even if the games are supposedly built on the premise of being social.

These observations seem to signal that designing social games means moving from designing social interactions to designing social distractions. Yet social games thrive on social networking platforms for a reason. Should their sociality, then, be judged with the criteria of social context and how it contributes to the social experience, instead of evaluating the social in gameplay? I will explore this starting from the broader contexts of social networks and online communication before moving on to studying particular games and their social design.

Social media and network theorists have emphasized the fundamental role of communication in social networks. No relationship is possible without communication, and the more there is relevant and mutually satisfactory communication, the more intimate the relationship. Therefore also in games the social has to be built on the available means of communication and the social exchanges it breeds.

In case of social games, Facebook provides the social substrate with its communication channels. Simultaneously, as the de facto platform for social games Facebook molds their sociality to its constraints. Yet games work as independent applications on the platform, and developers can take theirs beyond the platform constraints by implementing additional means of communication into the game.

While doing so, however, they begin demanding more from the users. More complex or different ways of social interaction than the ones provided by the platform itself might consequently reduce the games' accessible and spontaneous nature that powers the social exchanges.

An even more constraining factor spurs from something implied in the above, i.e. that Facebook use in its widely adopted form apparently rules out demanding players to access a specific application or site at a particular, shared time. This is the key difference of social, and to an extent of casual games, when compared to video games. Social games try to facilitate players' daily routines rather than the other way around: players do not need to reserve a specific time slot from their daily lives in order to play at all.

To circumvent these constraints and still be able to facilitate social play, social game developers have promoted asynchronous communication as the dominant form of social exchanges in their games, essentially following and constantly adapting the core communication functionalities of the platform. The resulting types of play have been described with terminology from studies of children's play: "parallel play" -- i.e. playing independently beside others but checking the others' progress from time to time.

Asynchronicity and parallel play have consequences for how fellow players' presence is experienced. In studies of mediated communication, a recurring research question concerns how our experience of social presence changes when communication shifts from immediate physical proximity to communication across distance.

Lack of nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and eye contact, lessen the sensory impact of the communication situation. On the other hand, these constraints make communication leaner, which can also accelerate the number of messages exchanged.

As a result of studying this area, scholars have introduced the term "social presence". It conceptualizes the salience of others when communicating across distance, and the salience of interacting with them in said situations. Social presence has been defined as the degree of person-to-person awareness that occurs in a mediated environment.

Immediacy is a quality that social presence relies upon -- and it is strikingly apparent that asynchronous communication is less immediate than one taking place in real time.

Clearly, social games in Facebook have had a weak impact in terms of social presence: they resemble the act of slipping the message under the door instead of knocking on it. Immediacy does not belong to the vocabulary of social games.

Without the prefix, "presence" is another theoretical concept researchers have been using to explain how people experience immersion and immediacy in virtual environments. Presence in this context has been described as a psychological state where the virtuality of experience becomes unnoticed.

In a highly social game of any kind, then, the virtuality or mediated nature of social exchanges should become unnoticed; they should be experienced as an organic aspect of gameplay. Or, the social exchanges should become so intense that they become increasingly memorable, as that is what tends to happen to emotionally salient experiences.

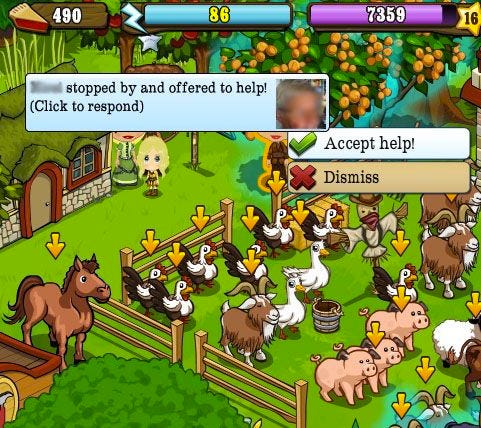

Neither seems to be overwhelmingly the case with social games at present. In many cases, social presence of others is introduced via distraction, such as a pop-up reminder for sending gifts, inviting more friends, etc. The smarter viral mechanics strive for such organic relationship, but in general, returning to spoiled crops -- again -- hardly counts as a uniquely memorable moment.

Then again, it is tempting to jump into such conclusions without proper sample of data from the millions of social game players out there: this is something that quantitative metrics do not tell you. Perhaps the weak but ambient social presence of other players is fitting for gameplay in a network where the primary function is to socially interact despite games rather than because of them.

Facebook has largely come to own "social graph" as a term that refers to people's relations within a network and how they can be globally mapped. The social graph visualizes and aggregates social relations one has in the context of a particular network platform.

The social graph implies that it brings additional value to using a social application or site, as it draws information from your social network. Social graphs are made out of information and identities, and it is up for the application to instantiate specific means of social exchange between you and your social graph.

The assumption is that leveraging the social graph will enrich your experience of the application. Social games start from the same presumption by laying your social graph out at your fingertips, readily available for game invitation requests, neighboring, competition, etc.

For understanding the role and substance of social ties embedded into the social graph, the concept of "social capital" is useful. Social capital is the intangible value of one's social network. The value to be gained from social capital does not lie in the individual but in the structure of her relationships and how they can be leveraged.

Theorists have identified two kinds of social capital: of the bridging type and of the bonding type. The first refers to weak ties which privilege exchange of information or new avenues of thought. The second refers to a more tightly knit web of emotionally close relationships. Whereas a friend leaderboard in a social game would represent an example of a social object that has a bridging function, a photo gallery from a social event full of tagged individuals would count for bonding.

MMOs, with their guilds, raids, and persistent demand of commitment (including peer pressure) foster the emergence of bonding type of social capital. Conversely, it would seem that social games in Facebook are typically low maintenance: any social capital that emerges is bridging in nature. It is there for viral purposes, such as for asking parts for collectables in the Facebook stream, but it rarely manifests concretely within the application and the gameplay there.

This observation is in line with the criticism of social games instrumentalizing relationships to the status of mere tokens with which to advance in the game -- yet this kind of design gesture can just as easily seen from a more positive perspective: complex social relationships are "stylized" for the sake of fun without the baggage the relations would carry if they were applied into the game in all their complexity.

Yet there is the emergence of an "Add me" culture in Facebook, where people are willing to extend their social graph to perfect strangers in order to include them as partners in the game. This phenomenon, even if exclusive to "hardcore" social game players, is highlighting how social graphs are transforming into interest graphs, which are centered around common interests and relations -- rather than relationships -- between enthusiasts.

Each post from the developers of popular social games is followed by a legion of 'add me' requests.

I'll conclude by translating the above observations into terms of customer relationship management: the casual nature of bridging type of social relations might drive acquisition, and engagement to an extent, but it is not optimal for retention -- for that, designs for bonding in social games are needed.

Historians tell us that cooperation and competition have always coexisted in human networks. These two archetypal vectors of social relations become evident also in how social games pit players to play with or against others. Unsurprisingly, it is the games with competitive aspects that pull strangers into the picture, whereas less competitive games stick to the social graph i.e. one's friends. There are no strangers in FarmVille.

Facebook is a particular case in this context, as majority of people do not hide behind the veil of anonymity or fake identity -- presumably this puts a dent to the degree of social exchanges with strangers people are willing to engage into. Still, games like City of Wonder are broadening the players' social graph in the game by giving the option for friendly exchanges or conflicts with unknown players.

Friend lists have become a standard user interface trope in social games, whether the players' social graph is modeled into leaderboards or into a carousel of neighbors. What the friends are called in the game does contribute to the perception of sociality.

In case you are persuaded to invite more "neighbors" to the game, the term "neighbor" sets them into an implied role where they do not necessarily directly access your space. Neighbors are there to provide assistance when needed. In MMA Pro Fighter from Digital Chocolate, friends can be invited to one's gym, thus associating with a communal space familiar from real life.

Besides neighboring and creating alliances, there are various transformations of similar entourage mechanics. Whereas these are largely based on players playing the same role and therefore standing equal to each other, games like Friends for Sale posit players into ownership relations where there are 'pets' and their owners, and the 'pets' can be put to do various quirky chores.

In the process the player is initiating a viral loop that addresses two friends. This is inherently more socially provocative, and potentially elicits more varied emotional responses. The takeaway is that assigning players into differentiated roles contributes to social emotions that contribute to stronger sense of social presence.

The above discussion can be summarized into three areas that are relevant avenues of development for short-term future of social games. All three hold seeds for creative game design solutions that can incrementally expand the sphere of social.

Space: First Frontier of Social

When parallel play meets asynchronicity, the combination effectively prevents shared space, and thus reduces communication modes available to players. Yet at the same time, it is evident that the shared space is paramount to authentic social experiences. Social game developers need to think how to overcome the most glaring constraints of asynchronicity without breaching into real time interactions. Games like FrontierVille are already figuring this out.

Space can also boost social through recognizable social spaces modeled into the game. In FrontierVille, familiar social events are stylized for the purposes of the game, and they reinforce its "familial" social flavor. Social objects, such as one's belongings on another player's property, can also accelerate the "social grind" -- i.e. motivate frequent visits between players.

Role Differentiation: Second Frontier of Social

Parallel play seems to lock players into roles where the available mechanics are similar to all -- if there is any heterogeneity it comes through decorating or choosing particular styles of play. Role differentiation is minimal, and consequently, so is lack of social variety.

More varied roles would organically pave way to a host of social interactions, such as trading. In MMOs, players can specialize into the role of merchants, which immediately give a specific focus to their social interactions in the game.

So far, social games allow superficial customizations of characters but no role differentiation, which would change the subset of mechanics that are available according to the role. With role differentiation comes reputation, another socially relevant aspect that enables grinding qualitative social capital by, e.g., helping friends.

Viral: Third Frontier of Social

Even if social games' dominant image appears to many as merely annoying spam in Facebook, the fact at present is that the virals are the concrete, in-your-face form of social in social games. Imagine most Facebook games without the viral feeds and ask yourself what would be left -- a somewhat compulsive single player experience.

For the social game designer, the fruit of frequent, incentivized sharing between players is social gratitude that reciprocating players feel for each other. This drives retention from a social angle. Socially acceptable virals, when incentivized properly from within the core mechanics, are both "shareworthy" for their sender and "clickworthy" for their recipients.

FrontierVille's way of taking social "too far".

Still, in terms of the substance of their virality, social games are virally challenged. Their virals seldom resonate beyond the game and its world, thus making them meaningless for non-players. The Old Spice Guy of social games remains to be seen. Truly viral always breeds discussion and thus accounts for meaningful social exchanges.

What if the large majority of social game audience does not want any more depth to their socializing through the games? What if social games, especially in their Facebook form, present playful excuses and distractions to whimsically interact with friends, instead of creating deeper social engagements tied to the game? If we build more sophisticated incentives for social proof, curiosity, presence, etc. will they come?

In a hit-driven and therefore increasingly risk averse business, few developers are willing to take the chance. Few games take advantage of the social graph beyond stylizing it to a graph of neighbors or allies in a visual carousel -- "your Mafia" instead of "your relationships" constitutes bridging in its lowest form.

What if that simply is the perfect fit for both the social networking mindset and the platform it engages with? Social game gurus are evangelizing the need of social innovation, but it might very well be that when we scratch the surface of social in social games we will, and we should find, more surface.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like