Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A sort of postmortem about Transformice, an indie massively multiplayer game started in 2010 by two people, now standing at 60 million accounts created.

Released in May 2010 out of pure fun by two developers on their free time, Transformice is a massively multiplayer platformer that gathered attention of the masses very early on through platforms like 4chan and SomethingAwful.

More than four years and many updates later, it now sits at 60 million accounts created.

While the game isn’t actually “finished” and still under active development, today I would like to share what is has been like during those four years, from the game viewpoint of course but moreover, monetization-wise. Because making a game is hard, but making money from it is even harder. Yay, numbers!

In 2010, Jean-Baptiste Le Marchand and I were full-time employed at a French videogame company, him as a developer and I as a graphic designer / technical artist. Jean-Baptiste had a history of creating small browser games for fun, and asked for my help in order to a new one, with better graphics.

Thrilled by his ability to quickly make a gameplay hilarious, I accepted and proposed him a gameplay with mice having to transform themselves into crates and planks in order to help their other fellow mice to cross gaps and get the cheese: Transform-mice. We quickly changed it for a super-mouse (the Shaman) summoning the planks and crates, but the name Transformice stuck.

Transformice splasher, 2010

The core gameplay loop was simple: climb your way up to the cheese, go back to the mouse hole, as one player (the Shaman) can summon planks and crates to help everyone. In about three weeks, we had a fully working prototype.

First prototype, 2010

We launched the game on May the 1st 2010 (we thought it would be funny to do it on French’s Labor Day) and we only shared the news on a single French videogames forum we were familiar with, JeuxOnline. Things were going pretty well and people were enjoying the game a lot, even with its great simplicity: no accounts, no cheese-counting, very simple brown mice and color-solid grounds. The physics engine (Box2D) and real-time multiplayer allowed extremely hilarious situations, and people got hooked fast. We added accounts very quickly to count cheese as a currency, so that people could use it to buy hats for their mouse.

Then, a couple weeks after launch, we’re not sure how but the SomethingAwful forums found out about us. The game wasn’t even translated in English, but the Goons didn’t care, and kept playing and yelling “OMELETTE DU FROMAGE” around. The funniest video in Transformice’s history (1M views) was made at this moment (I really recommend to watch it if you don’t already know the game, it’s a perfect summary).

As we quickly translated the game to English to welcome the Goons, pure chaos ensued. The moment SomethingAwful found out about it, 4chan was meant to follow, and our unique little server simply melted under the demand. Of course, this was the perfect moment for Kotaku, Rock Paper Shotgun, Indiegames.com and PC Gamer to write about us and make our bandwidth usage skyrocket a little more.

The server usage became problematic quite early on. We paid for the servers out of our own pocket, and there was no way we would be able to afford to pay for a dozen. That’s why we went for the fastest and cheapest solution of putting an Adsense horizontal advertising banner under the game, and opened up a Paypal account for donations.

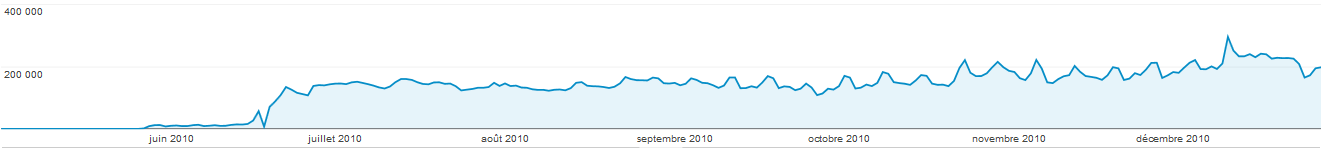

The advert banner performed well, with an average of 47€ a day, and allowed us to rent more servers. By the end of 2010, it generated about 11 000€, for an average 80 000 unique visitors a day.

The Donate button with Paypal gathered around 3000€ before we pulled it off by the end of the next year. The list of donators is still displayed on our website today, and most of the donations came from the US and Norway, but almost none from France despite being our home country. It’s just not in the culture.

This went on for months, where we would be adding more servers as fast as possible, trying to cope up with the massive influx of players, while being full-time employed, and fixing some bugs / add content (hats!)

At this point, we knew we had to take a decision: leave our full-time jobs and create a company to take care of the game (which already generated some income), or kill it entirely because we didn’t have enough free time for its needs. Obviously, we went for the former.

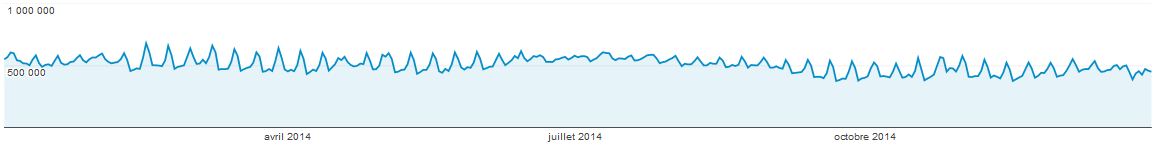

That’s how one year later, April 2011, we left our day jobs and create Atelier 801, and thrilled by the new additions and seasonal events we could make thanks to finally being full-time on the game, the playerbase slowly doubled, from 150,000 to 300,000 unique visitors a day.

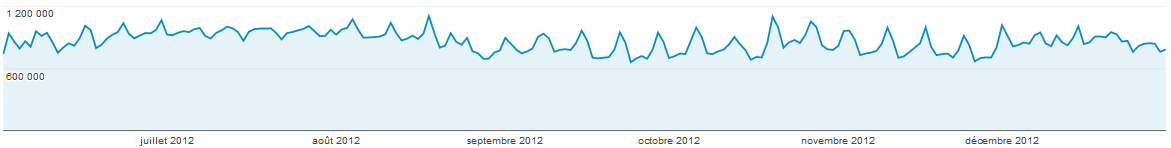

We had a very exotic player distribution : more than 50% of our overall audience came from Brazil, then from the United States (11%), Turkey (8%), France (7%), overall Latin America (5%) and Russia (3%). We made sure to localize the game in every language we could, to not leave any community behind, and it really paid off with Brazil and Turkey.

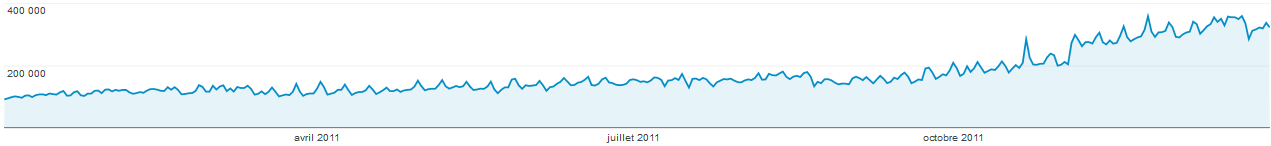

Despite those two countries not being really interesting to advertizers at the time, the advert banner performed very well, generating an average 280€ a day, even peaking as high as 1000€ by October, raking in 103,000€ for 2011. As a complement, and as the .swf file of the game was spreading around the web, we also added a quick pre-loader advert (that you could skip instantly), which performed at 150$ a day, generating 55,000$ for all 2011.

Thrilled by these numbers, we made some calculations based on servers cost and salaries, and realized that we could hire one more person to work on the game! We didn’t hesitate one moment, and recruited our most passionate moderator to be our Community Manager, in order to answer the thousands emails we were receiving and deal with moderation in game.

But the joy didn’t last long. See that big red bar on the advert revenue graph? That’s when we got banned from Google Adsense.

Atelier 801, end of 2011

We really took a hit at this moment. Since Google pays with a 60 days roll, the sudden ban of our account meant more than 13,500€ of unpaid clicks. We were left with three salaries and about 30 servers to pay for, and our main source of income had simply disappeared.

We immediately tried replacing Adsense with other advert agencies, but none were performing half as good, and numbers didn’t add up anymore. Jean-Baptiste and I stopped paying ourselves for a few months, in order to be able to pay for the servers and the salary of our Community Manager while working to sort this out.

Why did this happen? Suddenly our whole domain was blacklisted, without any warning or email, and not a single form available to inquire. Literally, there is absolutely no way to get in touch with any Google Adsense staff: your only chance is a user-driven forum, where people usually don’t know much more than you about what’s going on. One of them even snapped that we got banned because of our Donators page, and refused to answer any further.

New Year’s Eve passed, and we thought that having a full Wordpress website with a lot of content might get us unbanned, but we hit the same brick wall.

It’s only by tremendous luck that we got out of this: a friend of ours happened to go to the same school as one of Google’s employees, and a couple emails managed to get us unbanned in minutes. Never underestimate the power of networking...

It’s only then that we learnt why the banning occurred: Google bots detected that our banner was less than 150px away from our Flash game, which is against Adsense’s policies (always read the small characters!), and banned us automatically.

So, we reinstalled the Adsense banner by February 2012, but 150px is a large distance, and most of our audience with low-end computers and small screen resolutions weren’t even able to see it anymore. We let it run for a few months, generating around 150€ a day, but it still wasn’t enough for paying the three of us + the servers, and we were very bitter about the way the whole thing had been handled, so we decided not to depend on advertisements anymore: we were getting prepared to go Free-to-Play.

We took a lot of time to develop this with extreme caution, as it was a real shift for us. Will the players hate us for asking for money? Will we suddenly become sell-outs? Will the players stay?

We wanted an extremely fair and ethic monetization, making only cosmetics available, with a great majority still only available through playing, so hardcore players didn’t feel they fought for nothing, and very low prices. It was extremely hard for us to come up with price points. How much were we comfortable letting people pay within our browser-based, cute little mice Flash game?

We wanted to give our players the most out of their money: I completely re-drew all the items that we had (about 150-200 at that time) in Flash with different grayscale clips, in order to allow players complete customization of every area of color of each item.

Customization of each item could be unlocked against a large amount of cheese, or a small amount of hard currency, strawberries. We also chose about 20 cosmetic items to be purchasable with strawberries (and keeping them available through cheese too of course), and implemented 5 different fur colors to change the whole body of the mouse. As we were testing them, we purposefully showed off in the different rooms by wearing them ourselves, and players were VERY eager to get their hands on the fur-color feature.

With many fears in mind, and after six months without a proper salary, we removed all advert banners and finally released Transformice Free-to-Play on June 14th 2012. And it went… quite well!

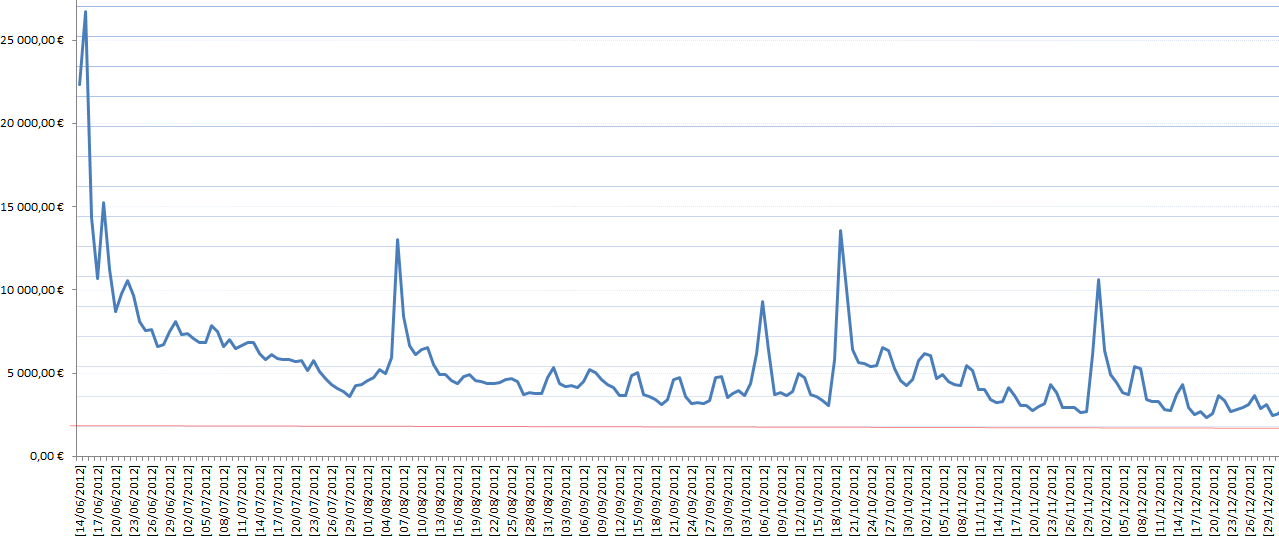

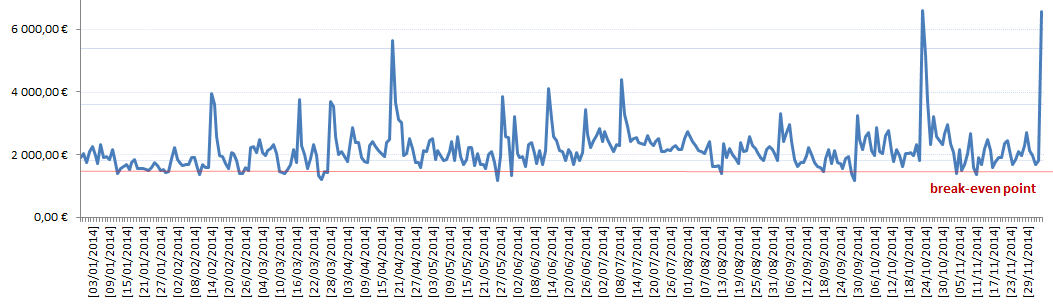

As you can see on the graphs, the player’s response was astounding. They were thrilled to be able to support the game they loved, and the first month generated more than 250,000€! We were flabbergasted.

We quickly hired a few more people, 3 developers, 3 community managers, one chief financial officer, and a sysadmin. With about 3 million active players and 40 servers to handle, we thought it was a good team scale, and it would allow us to sleep a bit better.

We also moved into bigger, more expensive offices by the end of the year 2012.

All in all, between June and December 2012, microtransactions generated 1,068,300€, with an average 5,262€ a day. Every peak on the curve matches a new content/seasonal update, with more hats and fur colors to buy, and the red line is our break-even line including the new hirings. It was at the end of this year that we broke our all-time concurrent players’ record, with more than 86,000 users online.

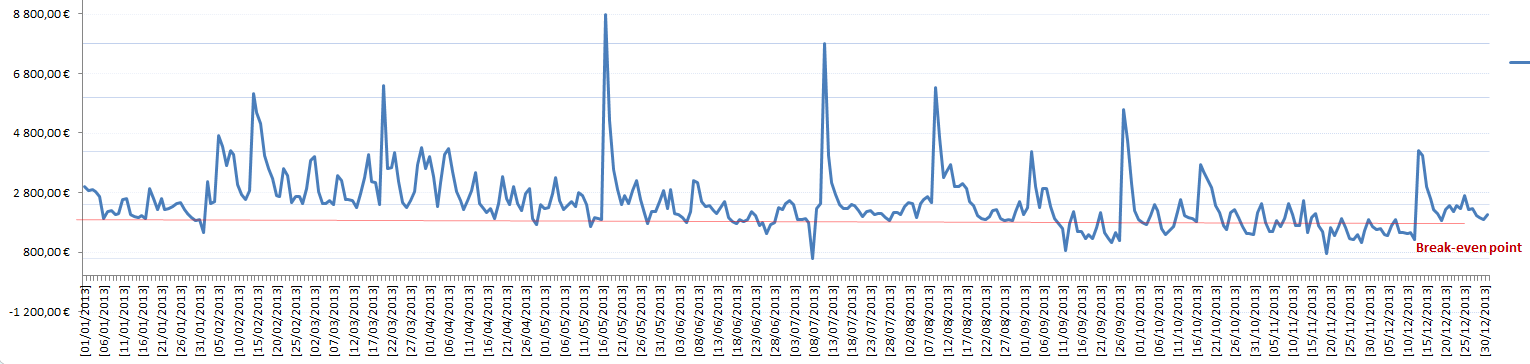

Months passed, and 2013 started slowly monetization-wise, flirting with the break-even. Retrospectively, this can be explained by the fact that we ran a frenzy winter event throughout all December 2012, featuring an Advent calendar that gave players rewards every day, and we gave away a TON of content (hats, titles, cheese, even hard currency) for free. In retrospective, it was a huge mistake on our part, because players can only wear that many hats at a time, and it hindered our sales for several months.

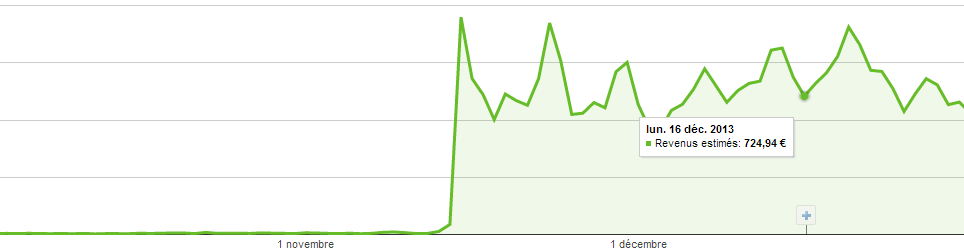

It got even more concerning around October 2013, and we decided to reactivate an advert banner next to the game on the website, but this time vertical instead of horizontal. We then observed that it wasn’t disturbing our players at all, and it performed a lot better than before (stabilized at 500€ a day, compared to 150€ a day early 2012). It provided a nice complementary income that allowed us to stay above break-even.

Looking back, 18 months of ads even performing as bad as early 2012 was still worth more than 100,000€, and we were fools to get rid of it.

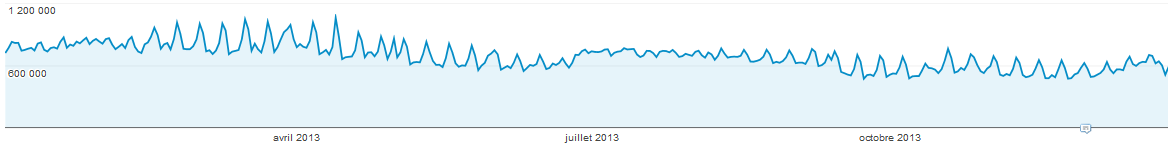

Meanwhile, the number of players was slowly decreasing, and the whole year 2013 saw a 15% drop in our active users.

Things weren’t looking too bright by the end of 2013, with the holiday’s season barely performing better than the rest of the year, and 2014 started grimly, January and February being usually slow months.

We then took one of our biggest decisions: to not give any free hats during seasonal events anymore, and sell them instead (against cheese/strawberries). It was only thanks to the frenzy 2012 Christmas event that we realized we were basically giving everything we sold for free during events, and while it was very appreciated, it put our future in jeopardy.

The decision was quite unpopular. Players complained a lot on the forums, and rightfully so: while we gave out badges and titles instead of hats, they felt that they didn’t have anything worthy to fight for anymore. Some players on the other hand were happy about it, because they didn’t want to play all throughout the event to get that nice Valentine’s hat, but mostly people felt we had become sell-outs.

It settled, eventually, and slowly but surely our sales went up. We were above break-even a lot more frequently, and while the number of players decreased a little, we were monetizing better.

In whole, 2014 generated 929,025€ in sales and adverts, and after paying for all charges and taxes, our benefit was 40,309€.

In January 2015, we managed to publish Transformice on Steam, and it allowed us to get some nice articles and a little more attention from the US community. At launch, the game peaked at 5 333 concurrent users, making it the 41st most played game on Steam. Therefore, we were able to sit on the Popular New Releases list on the homepage for almost a full week, and the game got downloaded 400,000 times during the first month. More than 120,000 new accounts got created through Steam during this month, and 38,423 of those played for more than an hour.

It is worth mentioning that during all those years, and before the Steam release, the only press we ever got was those four articles that I mentioned back at the launching of the game in 2010. It gained so much momentum by word-of-mouth at this moment that we never felt the need to do any PR, or talk to anyone in the industry at all. Retrospectively, we might have missed a lot of opportunities that way only because we were so busy improving the game, it might have hindered our capability to build a sustainable, long-term game development studio. We resigned from our first jobs in the industry and just did our thing in a corner, without looking around and paying attention to what others did, and that is probably backfiring for our other productions.

During those four years, we published three other games: Bouboum, Fortoresse and Nekodancer. While when all three united they gather around 300 000 unique visitors a month, and generate enough ad revenue to pay for the servers they’re running on, we’ve failed to promote these games out of our own community of players, revolving around Transformice. And to be only relying on a single game’s success is nothing short of worrying for the future of a studio.

We don’t have much to complain to be honest: we’ve got a huge dedicated userbase, a greatly successful game, and a rather regular source of income allowing us to run a 12 persons studio and develop other games. It’s only up to us now to learn all there is to know about marketing a game, and make the best use of all this potential that we have.

Time for the mandatory tl;dr What Went Right / Wrong!

1. Physics

Back in 2010, there was a kink for physic-based flash games, the most popular being Fantastic Contraption, and it definitely influenced us while making the game (and made Brian Fargo contact us!). Later came Incredibots, QWOP, Crush the Castle… All very fun in solo, but none of them included a multiplayer twist.

People love to mess with the physics engine by itself, but it’s becoming hilarious in multiplayer. Players toy with the physics, and basically we could leave them with a beach ball and they’d still have fun together.

It’s not as relevant today as people are less impressed by such features in browser games now, but the game came at a perfect timing with the genre.

2. Real Time Multiplayer

If you remember correctly, 2010 was a great year for Facebook games. In a world of desynchronized interaction, a real-time multiplayer game that could still be played in your browser was a great alternative.

Real-time multiplayer is rare on browsers, and rightfully so: it’s usually very demanding in resources, both for the player and the developer. Multiplayer in itself is a big piece to chew on for any indie game developer, but it’s so worth it! Playing together is really the core of a game for us, and that’s why we focus only on multiplayer games.

3. Accessibility

This one is tremendously important for any indie who wants to reach out to an audience. Why would anyone try your game if it takes so long to load and install?

Our game was weighing less than 1Mo, was playable on all desktop operating systems and browsers thanks to the popularity of Flash Player, and featured a “guest” mode for everyone who didn’t want to create an account to try it out. The registration is also quite easy: no email asked upon account creation, the players are incentivized to fill it in later with a small cheese and accessory reward.

All of this made the player’s tryout frictionless, a necessary feature in the browser-games world, where the attention span of a player rarely exceeds a couple minutes. It largely contributed to the viral part of our success.

We realized it later, but it’s even more important when you start reaching developing countries: their hardware specs are nowhere near the ones most of us are used to, but you shouldn’t let them out, because they’re players you want to reach! This leads us to the next point:

4. Localization

This is mainly part of Accessibility as well, but it deserves its own bullet point.

As soon as we saw English people playing on our little French game, we translated it to English of course, but we also did it for Brazilian, Russian, Spanish and Turkish very early on. Whenever we saw an emerging community, we would do our best to provide the game in their language (even in Arabic and Hebrew), and it proved to be more important than we thought.

More often than not, developing countries don’t have access to many interesting games. They are either not translated in their language, or too heavy to run on their hardware. Most of the big editors won’t try to market those countries, because either they’re not wealthy enough or not large enough, or the piracy is too high (hello Poland!)

This makes a HUGE reservoir of players you can reach. Small streams make big rivers!

We simply asked our players to help us with the translation, and they were more than happy to do it. Crowdfunding translation is a cheap (virtually free) and good quality way to go (players already know your game and will translate accordingly), even the big ones are doing it. Export a csv into Google Drive and you’re good to go.

Even if some countries will never spend a dime in our game (either because they can’t afford it or don’t have any available mean of payment), it doesn’t matter, as it only makes more players, which is the most important parameter in multiplayer games AND free to play games. More the players, funnier/more competitive the game gets, and further it reaches.

Only roughly 30% of the worldwide population can read English, as Rami said, games often suck at inclusivity.

5. Two-people team

This is both a good and a bad thing.

Good because being only two speeds processing tremendously: when you’re working with a bigger team, you’re more at risk that someone can’t keep up with the pace, slowing everyone down. There are numerous indie teams failing that way: starting too many. It’s even better if you can cover all aspects of development alone, but it doesn’t happen much often.

JB and I are very complementary, and we maxed the different competences while minimizing the number of persons involved, allowing us to develop very fast.

The downside of this of course is that it quickly becomes impossible to make bigger games, and it’s very hard to keep up with the pile of the most annoying bugs multiplayer games always come up with, and the management of hundreds thousands players.

But in the end, it’s because there were only the two of us that Transformice got released in three weeks of development.

6. Graphics

Not to be too self-congratulatory here, but the art style turned out to be a good part of our success, in its own simplicity. The choice of cute little mice contrasted very well with the unfathomable cruelty that awaited them, and the sight of a literal horde of adorable critters running all around the screen often triggered laughter. Even if the graphics were simple, they were slightly above the average Flash game you’d find on game portals, thanks to the experience gathered with Flash at my previous job, and people seemed to like it.

7. Player Feedback

Even if our players keep yelling on our forums that we never listen to them, we actually do a lot, and did so very early on in the development of the game. We took in players’ feedback quite regularly all through the game’s life, taking in suggestions about new content, and it allowed us to stay close from our community, even if most of the time, we have to adapt all the ideas to make them fit correctly with our game design.

We try our best to listen to what they want but we don’t do exactly as they say, because they often don’t know what they want for themselves.

1. Two-people team

When we started to develop Transformice, we didn’t give much thought about the consequences. We just wanted to make a small and fun game on our free time, without actually realizing what was coming for us: who would even think about making a multi-million players MMO when you’re only two persons? We missed a lot of opportunities because we weren’t able to cope up with the initial rush. Thousands of players tried to reach the game during the first months, and simply couldn’t, because we didn’t have an appropriate server scale. The more players you have, the higher expectations get, and with only one developer and a graphic designer, it was just impossible to cope up with the bug-fixing and new functionalities demands, let alone business stuff that we also had to do.

2. Read small characters

Retrospectively, our Adsense ban transformed in a good thing, but at the moment it certainly wasn’t, and it put a lot of physical stress on us. If anything, we have been careless with how we generated money, and when your business model only relies on a single source of income, you better make sure you know exactly what you’re doing.

Never try to do anything shady and think you will get away easily either, it’s the best way of taking risks to screw everything up, and karma will gladly remind you so.

3. Hiring too fast

When the microtransactions took off, we were so relieved that we could finally scale the team up to more reasonable standards that we didn’t pay as much attention to the hirings as we should have. We grew from three to ten persons in a less than eight months timespan, and we weren’t prepared for it. Some mistakes were made, some tensions arose, and suddenly employees management had become a thing without us two realizing. We always tried to provide the best working conditions, but shrugged off project management entirely, relying on everyone to find stuff to do on their own and without setting proper goals. This is something we’re getting better at lately, but it took us a very long time to realize how important it was.

4. Not paying attention to mobile

All during those four years, we shrugged off a mobile version of Transformice, not even allowing ourselves to think about it. Come on, it’s Flash, it’s heavy processor-demanding, and you need a keyboard and a mouse to play properly, how can you even closely emulate that on mobile devices? We were too busy coping up with the PC version anyway.

While we don’t have any numbers or experience yet to back up this opinion, we probably should have taken it more seriously earlier on. When we tried our hand at mobile with a spin-off runner version set in the Transformice universe, so many people were disappointed it wasn’t the real game, even if it wouldn’t be as comfortable as on PC.

We finally wrapped our head around it a couple months ago, and tried to build a small version using Adobe AIR, which to our great surprise proved to run quite smoothly on Android devices (and completely unusable on iOS). So much for preconceived ideas.

We are going to work some more on it and release it in the next few months.

5. Monetization: we had no idea what we were doing

When we decided to go Free-to-Play, once again we didn’t pay much attention to what other studios did around us. In our heads, you could only do F2P in two ways: the fair, League of Legends way, and the horrible Zynga/King way. We were so stressed out that players would hate us that we went for the most fair we could, but that also meant underselling our products.

Once they’re set, it’s always easier to go down on your prices, but you can never raise them, and we learnt it the hard way. We didn’t do our homework and had no idea about ARPPU, break-even costs, business plan or projections.

It really struck me at one masterclass, given by the awesome Nicholas Lovell: he asked us to raise our hand, and put it down whenever we weren’t comfortable with the amount of money our players could spend in our game. And he started counting, 1$, 5$, 10$, 100$ etc. Most hands were down at about 500$, and he simply told us “there’s no good answer to this, other than that you shouldn’t have let your hand down. If players want to spend so much on your game, you need to allow them to do so.” And he was right. We were the worst to decide the pricing of our cosmetic items, because we priced them according to the time it cost us to develop, not how much valuable it would be to our players. At the launch of Transformice’s microtransactions, and long after, you could get everything there was to buy for about 20-30$. We didn’t allow “superfans” (or “whales”) to stand out, and we couldn’t go back on our pricing. We only arranged that a little by adding more content and more features, so people can spend a fair amount of money, but we still don’t have any money-destructive mechanism to make the superfans stand out from the crowd.

While we’re very grateful for the F2P model and entirely aware that Transformice couldn’t be monetized in any other form, we’re a bit frustrated with the model, as it’s a LOT of work for a small indie team, and it just never ends. We want to explore other methods of monetization in the future, and even going back to premium for our next game Dead Maze.

Transformice sure was a hell of a ride for us, and it still is. We’ve learned so many lessons from it because we were starting so much from scratch, it was pretty rough sometimes, and we probably missed out a lot of opportunities due to our lack of experience, but overall we were so tremendously lucky to be able to live this adventure. We firmly believe luck is an important factor in game development, even if it only means having the right product at the right time.

We are still working on Transformice, but also developing completely different other games, in order not to be a one-game studio anymore and become a stable, long-term company. We hope all our fiddling and past errors will be useful for that purpose.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like