Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How we wrote the story for our upcoming release Sunset with the aid of a script-writing tool and enjoyed exploring its themes in spite of initially mixed feelings about creating a game intended primarily for people who enjoy playing games already.

Sunset is a game in which you fall in love with somebody you never meet – as the passion rises, the city outside explodes and burns. We were super excited about that idea, but we also wanted to reach more people with Sunset, so we did some research and added a million other things.

The original idea for what became Sunset is almost as old as our studio. Ten years ago, we wanted to make a first-person game in which you play some sort of invisible ghost, changing things in an apartment by night that influenced the lives of the inhabitants during the day. A few years later, after realising that one of the things we like most about games was well-defined characters in well-defined environments, the main character of “The Apartment” became an immigrant cleaning woman.

More years passed. Years in which we made The Path, Fatale, and Vanitas, as well as all sorts of prototypes before Bientôt l’été and Luxuria Superbia. We were preparing to continue our merry quest for adventure in video game creation land with An Empty World and The Book of 8 when we suddenly noticed that lots of people had started paying attention to the kind of games we really liked: games where you are immersed in the atmosphere of a simulated environment with the freedom to explore.

On closer inspection, we noticed that the most appreciated games in this new genre – if that’s what it is – had something in common: a first-person perspective. Our love of characters had meant that we never used first-person, except for the spirit in Fatale, but we remembered this old idea for “The Cleaning Woman In the Loft”, as the idea was called in the wiki where we keep all our notes, and figured we should give it another chance.

We immediately started imagining explosions and fire and smoke, maybe because we associate the first-person perspective with shooter games. We thought this violence would mesh well with a romantic story. There would be a sprawling city on the other side of the windows and as the protagonists fell in love, the fires in the city would express the rising passion in their hearts.

Then we did some more research.

As we wanted to work within a relatively established area of the industry, we started reading up on what people enjoyed in particular about these games. We’d already learnt the hard way that our own love of games rarely aligns with others. We didn’t want to make the old mistake of working purely on instinct and then struggling to understand why players didn’t get it.

Scouring forums and blogs and reviews, one thing became abundantly clear to us: if a game doesn’t focus on action or competition, it needs a compelling story. This might seem obvious to most of you but we were quite astounded by this discovery (it just goes to show one should never underestimate the stupidity of an artist). We’d never actively created a narrative for our games before – even though we’ve always been labelled as creators of narrative games and (duh) the name of our studio is Tale of Tales (that’s two instances of “tale” in one name!). We’re usually content to just explore a situation without any real storytelling or plot advancement, or much of a backstory for that matter.

We’d always been reluctant to write stories because we were never confident in our own writing skills. With that in mind, we adopted the role of students and began learning to become writers, at least for the purpose of this one project. There’s an ocean of advice for aspiring writers on the internet. It’s like everybody wants to be one and everybody either really needs to give or receive information on how to become one and be a good one. It made our heads spin at first, but then we found the formula.

A little program called Contour caught our attention. We were simultaneously amused, aroused and titillated by the confidence with which its creator, Jeff Schechter, proclaimed to offer the exact recipe for successful scripts. He didn’t promise that a story following this recipe would be successful but he did convincingly demonstrate that most successful films and novels could be broken down to fit within the structure the program was built around.

At its core the Contour method is a classic three-act structure broken down into 44 explicit plot points. Each of these plot points covers a specific message and together they build a story arc. Now that we’re acquainted with this system, we see this structure everywhere. It’s very pervasive and very powerful. Knowing and recognising the formula doesn’t prevent these stories from having their intended effect on us emotionally – it just works!

I’m not going to claim that our story will work. But Contour did offer us an almost paint-by-numbers way of writing for Sunset. We had already collected a lot of ideas for characters, situations and events, many of them recorded during lonely car rides between our home and Paris where Auriea was attending a life drawing workshop. But now we were able to structure these into a story that had a chance of making some sense, if only emotionally.

This is why Sunset consists of 44 sessions: one for each plot point. According to the formula, in the first act, the protagonist must be an “orphan”, somehow separated from their community, different, maybe an outcast. Since our story needed to serve a first-person game, we immediately ran into the question of who the protagonist is. The player character is obviously the most important one but since they are controlled by the player, we can’t force their story arc too much. So we decided to focus on the unseen owner of the apartment as the primary character in our three-act story. Although, Angela and Gabriel do find themselves in a similar situation, so they share this role a bit.

Both Angela and Gabriel are symbolic orphans. She’s an immigrant whereas he has been removed from his social position and separated from his family. During the first act, the villain must be introduced. In Sunset, this is the ruthless dictator Generalísimo Ricardo Miraflores. Emotional tension between the protagonist and the so-called “stakes character” must also be established (i.e. potential romantic interest), specifically a result of a threat from the villain. This is an area where Gabriel and Angela share roles: they are concerned about each other as both suffer in different ways and can both help one another.

In the first part of the second act, the protagonist becomes a “wanderer”. We don’t want to spoil the story, but let’s just say that people and things are moving around at this point in Sunset. This part of the story ends with the protagonist figuring out a way to defeat the villain.

In the second part of the story, the protagonist becomes a “warrior” and the fight is on. The villain is confronted and the fancy apartment becomes a war zone, so to speak. At the end of this part of the story, things seem completely bleak and desperate. We feel that there is no way that the protagonist can ever defeat the villain.

But then he becomes a “martyr”; he gives up on his old ideals and principles, embracing the knowledge he has acquired along the way. And thus the protagonist conquers not only the villain, but also the hangups that were preventing him from leading a full life. There you go, we just spoiled the story of Sunset for you!

Not really.

So it would seem that we “sold out”, gave into “The Man” and set out to create some “mainstream pulp”. Part of us felt rather uncomfortable about this actually (the part that is usually referred to as pretentious and artsy fartsy). We think of all of our games a little bit as our children. We love them no matter what other people say of them. Sunset was feeling a bit like a bastard child: a mix between what we wanted and what we thought people would appreciate. But as we dove into the source material for our story, we really started to enjoy the journey. And Sunset was quickly adopted in the Tale of Tales family.

We had decided to set our story in a foreign location, in the past because this would give us and our players some distance to allow ourselves to believe in the fiction. Since we know that the large majority of the people who play our games are either from the US or the UK, we decided on Latin America. There’s some interesting political and social friction between North and South America, Spanish is a second language for many US citizens, and Latin America is at least partially part of the Southern hemisphere while still being sufficiently modern to host the skyscraper city that we needed for Gabriel’s pad. It also happens to be a prime location for left-wing revolutions and right-wing military coups (we wanted the conservatives to be the bad guys because that worked best with our characters).

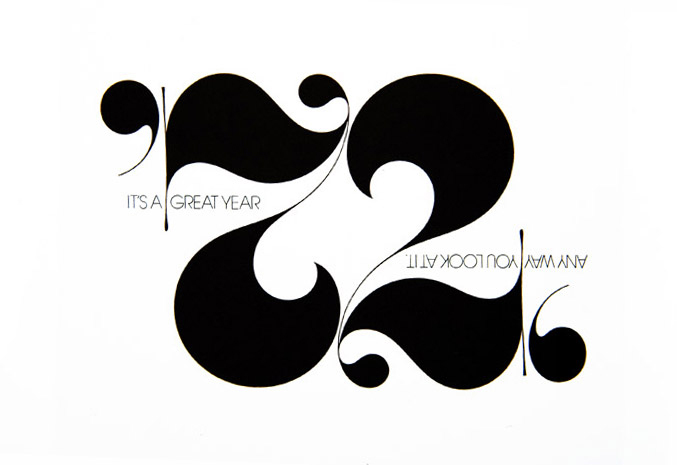

For the time period, we randomly called out “1972!” and somehow stuck to it. As it turns out, 1972 is a super interesting time. It’s when the 20th century broke in two and different visions of society clashed head-on. The conservative mundane well-to-do bourgeoisie was confronted with the escalating demands for liberty and civil rights from countless minorities. In 1972 the world shifted from a modern fairy tale land to a hard and cynical reality. We had discovered the man behind the curtain and still live in the shadow of that schism as the postmodern crisis remains unresolved.

But as happens often in turbulent times, the friction between cultures gave rise to an explosion of creativity.

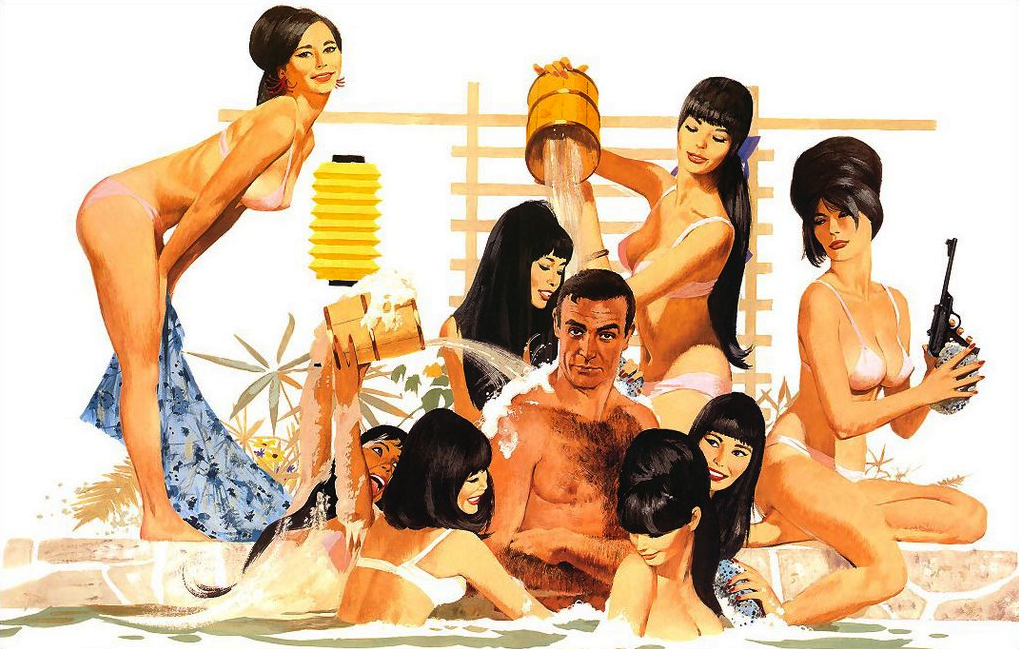

As we dove into that source material, we discovered a lot of things that we loved. Fondness for the early 007 movies was something that Auriea and I Bond-ed over when we met in 1999. We love the suave man-of-the-world attitude the definitive secret agent holds and find the sexy sexism highly amusing (it’s doubtful that you could get away with that stuff anymore). Sunset is not an action game, but it does have an element of spying and the apartment has its fair set of gadgets.

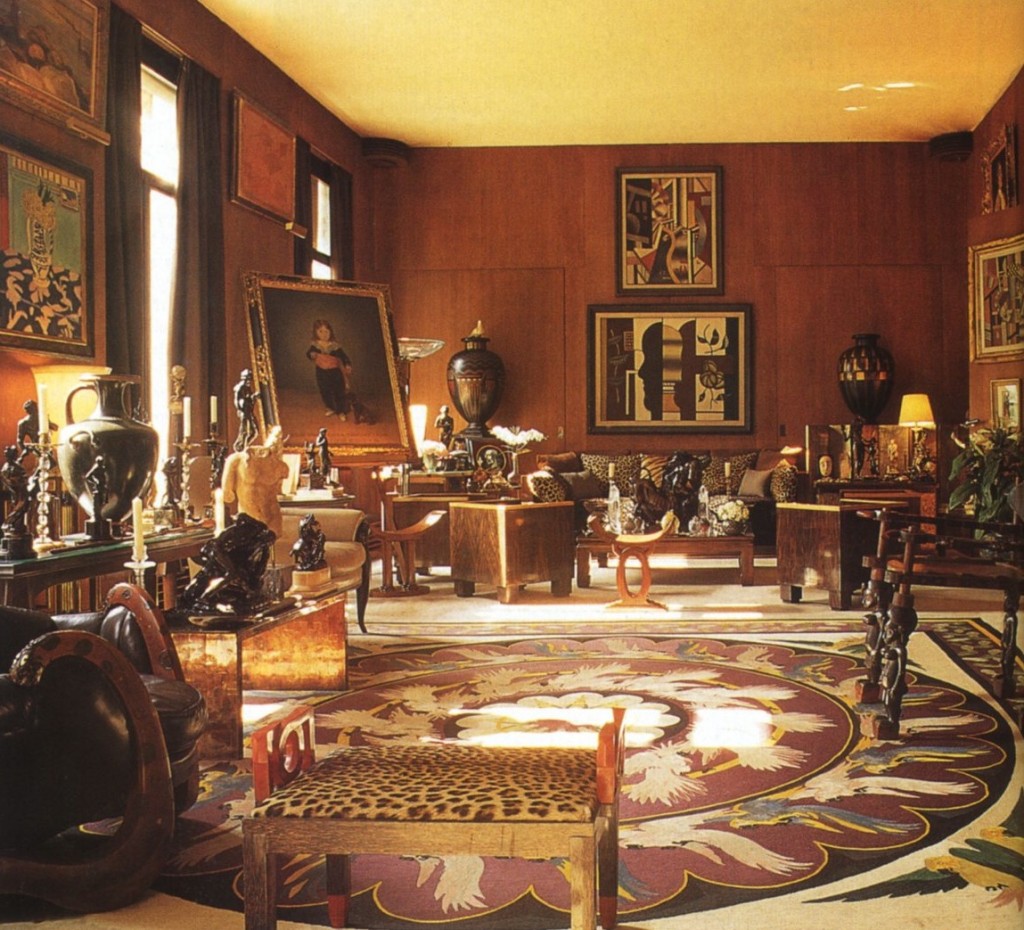

Time for a confession. I own a moderate collection of Playboy magazines from the 1960s and 1970s. I love the smell of old paper and yes I not only read the articles but also look at the pictures. In one of those copies, I found pictures of the perfect bachelor pad, equipped with the latest in technological comfort, a duplex penthouse destined for the heart of a metropolis. In other words: the perfect mansion for our disgruntled intellectual Gabriel Ortega. He doesn’t appreciate the sleek minimalist modern swingers apartment one bit. This is how the other side of seventies aesthetic enters: eclecticism.

We had been looking at pictures of Yves Saint-Laurent’s apartments that were circling around when his partner was auctioning off many of the art and design pieces the couple had collected over the years (somehow we had ended up on a mailing list that all the fancy invitations for these auctions get sent to). Beautiful stuff in overwhelming combinations: ancient Greek sculptures, cubist paintings, art deco furniture, Louis chandeliers, salon statuettes, religious ornaments, lush flowers, all together in a dizzying whirl that was so seventies! We wanted some of that in our game.

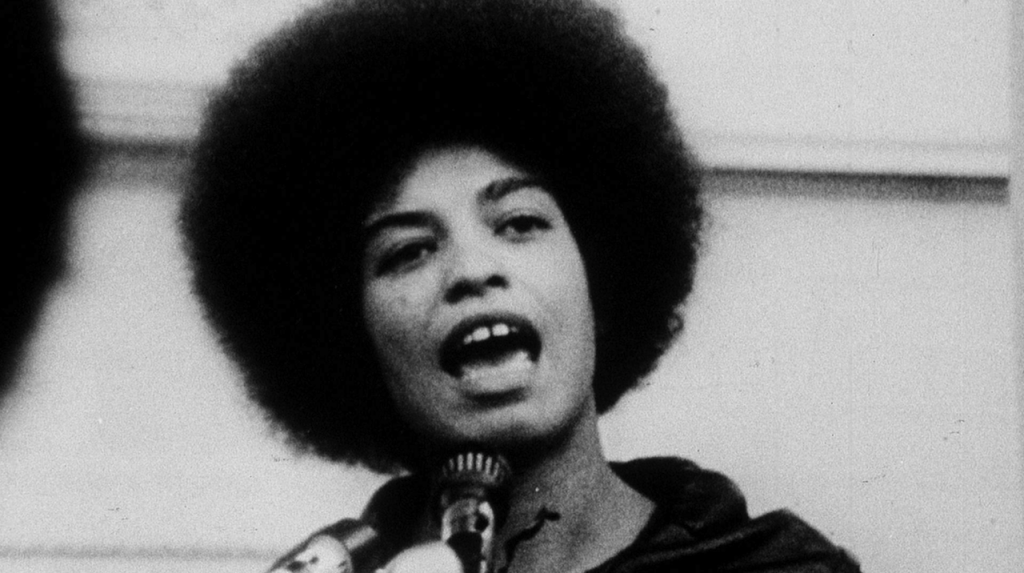

The final, huge, piece of the narrative puzzle was blackness. Auriea is black. In fact, she’s a black American immigrant just like the player’s character. 1972 Is the year when the trial against Angela Davis took place. It’s a long and complex story that by now we know way too much about but suffice it to say that this was a crucial point in the American civil rights movement. The trial demonstrated exactly how racist (and sexist) the American establishment really was and Miss Davis became a symbol for Black Power, almost as prominent as Malcom X and Martin Luther King.

It’s been a joy to immerse myself in that history. It’s not something many black people talk a lot about and when you’re in a relationship with a black person, the color of their skin doesn’t really remain a topic of acute interest for very long. Researching Sunset gave me the opportunity to understand the struggle that black Americans are still going through on a daily basis. I was moved to tears by Angela Davis’ biography. So we named our character after her. It is ultimately her insight into our society and her energy to fight that inspired the revolutionary narrative in Sunset.

We feel current times could use a bit of the ‘hope for a better world’ that still existed in 1972 and the belief that humans can create such a world, for all its occupants. If you get anything out of Sunset, we wish it to be that.

Embracing several accepted game conventions has been a new and exciting development for us. In the past we tended to approach videogames as typical media artists: you look at the technology and break it down and do something with it that you feel makes more sense than how the technology is normally used. This is a great process for discovery and innovation but it is slanted heavily towards the creators and medium itself, not the people engaging with it.

We’ve always wanted to create for people. That’s why we started using computers and the internet in the first place – it’s why we make videogames. The desire to innovate, to do things that haven’t been done before is a sort of reflex for us and it has led us astray, away from many of the people we wanted to reach in the first place.

Sunset is still filled to the brim with things we find interesting and haven’t seen anywhere else, but we’re working hard on wrapping all of that up in a package that is fun to play. It feels a bit like preparing our home for an evening of entertaining guests. We want to be good hosts!

Somehow, along the way the story of Sunset and the world we’ve built up around it have become a vehicle for many themes and concerns that are dear to us. The whole thing has quickly become an elaborate metaphor for how we see the world. But we’ll let you discover that yourself.

— Michaël Samyn

This article was published first on Continue Play.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like