Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A look at how distribution and visibility have changed as Steam has moved from Curation, to Greenlight, to Steam Direct.

There is a lot of talk about Steam’s policies these days, and almost all of it is (IMO) wrong. The reason is that there are three distinct ages of Steam — Curation, Greenlight, and the one we’ve just entered. The Age of Rocket Fuel.

There are lots of other online stores that operate under a Curation model, and it’s well understood. There are many that operate by letting users choose content that is sifted to the top. There are none that operate like Steam in the Age of Rocket Fuel, and if you don’t understand that Steam has changed, you’ll be wrong.

Let’s look at the distinctions between each era, but first let’s look at what Steam is. In simple terms, Steam is a distribution platform and an ad platform. The distribution platform side of it handles hosting your game, taking people’s money, managing their libraries, paying developers, and so forth. The ad platform handles showing your game to people.

Now most people don’t think of Steam as an ad platform, and that’s because Steam does not charge for ads — they dole them out to all the products on Steam, in a variety of different ways. Regardless, the most important thing Steam does for the games it hosts is provide visibility (ie, ads). The thing about visibility is that it has a very clear value — ads are bought and sold every day on Facebook and Google. The fact that Steam gives them away for free doesn’t stop us working out what their millions of impressions are worth, in broad terms.

So, with that in mind, let’s look at the first era : Curation.

During Curation, both Access to Distribution + Ad Featuring are hand selected by Valve employees.

Between 2003 and 2012 Steam hand picked which titles would be allowed on their platform. Beginning primarily as a host for Valve’s titles, they slowly expanded to host third party games in 2005, and expanded that to a suite of titles by the time 2012 came around. It’s notable that during this period Valve (along with XBLA to a lesser extent) pretty much created the Indie Game Renaissance. They did this by providing a distribution platform for hand chosen indie games — but more importantly, they did this by providing those indie games with millions of dollars of free advertising by placing them on the front page and featuring them during sales.

At this point, success on Steam was 100% down to the tastes of the Valve employees who chose which games to distribute and to feature. This is the golden age of Valve as Indie Kingmaker.

The second era began in 2013, with : Greenlight

During Greenlight, Access to Distribution is placed in the hands of the public, while Ad Featuring is still hand selected by Valve employees (with a transition in the late Greenlight period).

Greenlight opened the gates to anybody with $100 to be able to list their game on Steam’s ‘Greenlight’ section, where players could vote on whether the game should be allowed on to Steam proper. Each month Steam would pick the games with the most votes, and allow them a full Steam account that they could use to release their game when it was ready.

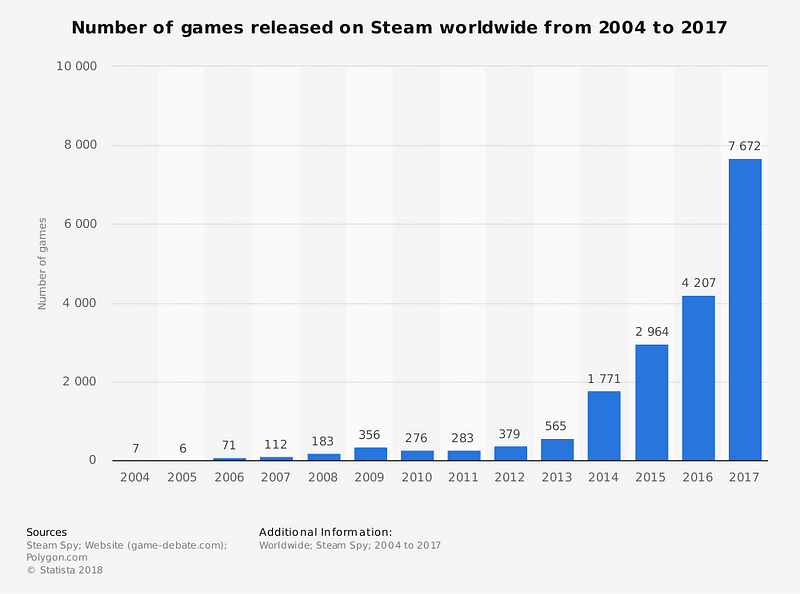

During the Greenlight era of Steam, the number of games released each year rose from 500 in 2013 to 7000 in 2017.

In essence though, Greenlight moved the power of choosing what went on Steam from Valve employees to Steam’s users. Steam still retained a lot of control over how featuring and visibility worked for different titles, meaning they retained their ability to Kingmake. While they no longer decided who got on the platform, they did decide what their players would see.

They managed this in a variety of ways, but the primary mechanism was to show all games to about a million people, and then judge how much they would get shown in the future on how well those million people responded (these are ‘visibility rounds’ in Steam’s parlance).[1] They did this at first manually, and later moved to a primarily algorithmic system. Their ultimate stated goal was to show players games they’d want to buy, and they do this by crunching the data they have to hand.

Now with the 2017 implementation of Steam Direct we move to the third era : The Age of Rocket Fuel

Towards the end of the Greenlight era, the Greenlight process had become essentially a formality. Valve had growing confidence in their ability to show users games they would want to see, and therefore were happy to allow any game distribution on the platform. They were approving hundreds of games a month via Greenlight, and allowing thousands of games to be released each year.

In essence, Steam is now a distribution platform for any game that wants to release there.

What about the ads, though? Visibility is not open or free (beyond the roughly $2000 worth of visibility Valve give to every game on launch). Visibility is now in the hands of the algorithms that, to the best of their considerable ability, attempt to match your game with people who want to buy it (and they show people an IMMENSE numbers of games — the front page alone showcases more than 20 titles, and changes each time you view it). In the previous two eras, Steam would do your marketing for you. Now, you need to do your own work to tell people about your game, and bring them to the platform.

If you do though, Steam applies the Rocket Fuel.

If your game resonates with their users, by being fresh and appealing, by giving them what they want to play, by being widely talked about elsewhere, by having ads on the side of every bus — Steam will take that game and magnify the impact of everything you’ve done a hundred fold. Steam have a massive, massive stack of free ads they hand out to everyone who gives their users what they want.

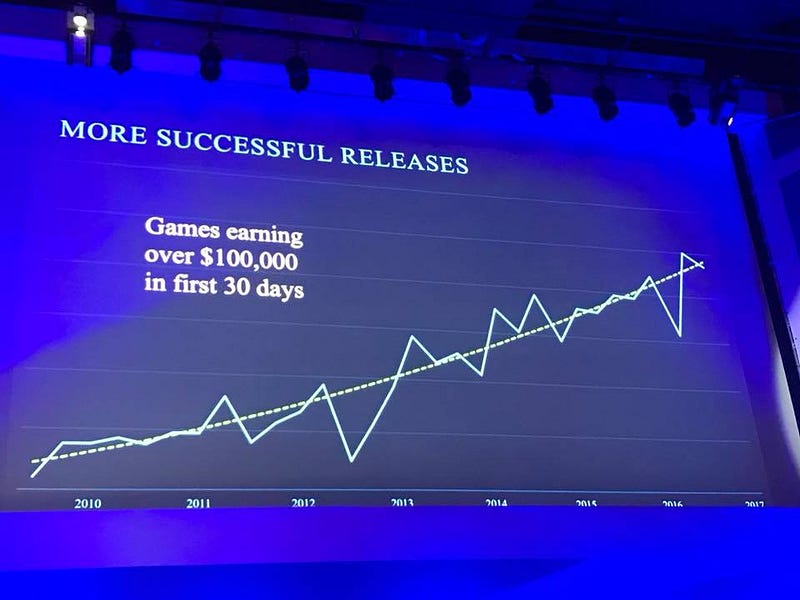

Image from Valve’s presentation at White Night, care of @steam_spy

Now, Steam aren’t doing this altruistically — they want to sell the most games possible in order to collect 30% of the largest possible pie. But they’re doing it effectively. In fact, they’re doing it more effectively than any other platform to date. The graphs above (courtesy of Steam dev days) shows that Steam are helping more developers make more money than at any other time in the history of the platform. Their policy of “Showing players games they want to buy,” has indirectly helped a massive number of developers create businesses and earn their livings.

In essence, Steam has the ability to signal boost quality out of the mire, and to give the audience what they want — and they’re refining that ability with each iteration. By getting people out of the equation, they’ve actually massively improved their ability give their customers what they want — not what tastemakers decide they should want.

Yet despite all these changes helping more developers sell more games, there’s been a lot of pushback that “Steam has it wrong,” and it’s easy to see why. There are lots of people who are acting like the playbook hasn’t changed. They believe simply releasing a game on Steam will bring them all the ad impressions they need. Or they make the sort of game that wins awards, is loved by tastemakers and would have been curated to success in the past, but that when given a choice the audience doesn’t actually want. Or they simply worry they don’t understand how it all works now, and are scared that more people means less opportunity.

Even though we’re in the biggest market ever for indie games, we’re also in the biggest market ever for indie games. The number of successes has been rising, but the number of failures is going up even faster.

Steam is unlike any other store currently on the market, and navigating these waters can be hard for developers. If you built a business on Steam in the Curation + early Greenlight eras it’s entirely possible you learned to make games for Valve staff and for Insiders — and not games for the actual Steam audience. That can kill you in the current market. Make games for the Steam audience, however, and Steam will apply the Rocket Fuel to propel your game in front of the eyes of millions.

[1] It’s worth noting that these million impressions would cost $2k or more if you had to buy them on the open market. Your $100 fee for Steam Direct or Greenlight directly gets you 20 times that value in advertising, but that didn’t stop people complaining about it endlessly at the time.

A final plug : if you’re interested in hearing a lot of smart people (and me!) talk about the current market and business of indie games, there’s an online forum coming up that covers these topics and more. The Business of Indie Games runs 24th-27th July— and they have free passes avaliable to watch it during that window.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like