Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this in-depth research paper, the UK's Strange Agency uses its proprietary software to analyze the Tomb Raider series and empirically compare it to other games with 'stealth' elements, with thought-provoking results.

October 11, 2006

Author: by Strange Agency

Computer game publishers, games magazines, review sites on the web; anyone promoting games just love to put them in genres. You come across it all the time. Retailers shelve games by genres, games magazines review in genres, it seems almost the number one requirement that games have to belong to a genres before they are accepted into the marketplace..

In Strange Agency we wanted to understand games in a more rigorous and objective way. We developed advanced software systems to do just that. One of our starting points was game genres. There are a number of good reasons for this, which will become apparent as this report develops, but the first is that it roots our investigations firmly in the games industry. We start where the industry starts; or rather, we start where the industry has gotten so far.

On the whole genres, for any communications medium, are a fuzzy but an agreed means of categorising games, films, novels and so on. So, whether we like it or not, genres do say important things the communications medium, of games.

There are other good things about genres. If you are a sneak-em-up fan then you will most likely be happy to play a new game in that genre. You will probably find that the controls for the new game will be much the same as for other games of the type. You will use the same keyboard keys, the same joypad buttons and gismos to select, pick up and discard objects, for instance, and if there are differences they will be slight and you'll soon work them out because you're an expert.

Tomb Raider: Legend

In our Strange Analyst software’s database we have 101 games genres, all in active use by someone out there in the games industry. Some of these are highly idiosyncratic ones, such as ‘Sci-Fi Turn Based Strategy’ and ‘Virtual Pet’. Others; ‘Action Adventure’ and ‘First Person Shooter’ are more familiar. The problem is that people often feel free to make up genres to suit their current purpose rather than sticking to the culturally agreed ones.

For basic research purposes we work with a far smaller number of genres such as: action adventure, action shooter, adventure, beat-em-up, platform, puzzle, racing, rhythm action, RPG, simulation, sports, strategy. This is a good working list and most games can be attributed to one of them. Most of the 101 genres can likewise be seen as ‘sub-genres’ of these. In our next STAR we will undertake a detailed analysis of what it is that characterises some of these game genres.

But what does it mean to ‘calculate’ with genres? How do we do this?

Activity is at the heart of gameplay. Activity defines game genres. Our in-house software, Strange Analyst, and the database it feeds contains data on just under 7,000 distinct games; around 20,000 if you include the same game name across a number of consoles. We currently use 48 distinct activity groups in order to analyse games. Of course, we can’t tell you how we do this but the weightings for each activity we attribute to each game are calculated by in-depth, software analysis of raw data on games we derive from the World Wide Web.

We use this data to form activity profiles for each game. We can then profile games against each other, select a number of similar games and calculate an average profile for them and also calculate a whole genre and see how individual games in that genre compare with the norm.

By way of illustration we will undertake a brief analysis of a franchise, ‘Tomb Raider’, and compare this against a series of ‘stealth’ games: Splinter Cell, Deus Ex, Metal Gear (Solid and Acid) and Thief. Our principle aim in this free report is to demonstrate how not only individual games but also genres can be measured and quantified and thus become a practical and valuable working tool for games designers.

The Tomb Raider franchise is one of the most readily recognised the world over and Lara Croft is one of the few game characters to have crossed over into mainstream popular culture. Its very familiarity in itself makes Tomb Raider an excellent case to study. What is there still to learn about such a well know and successful game?

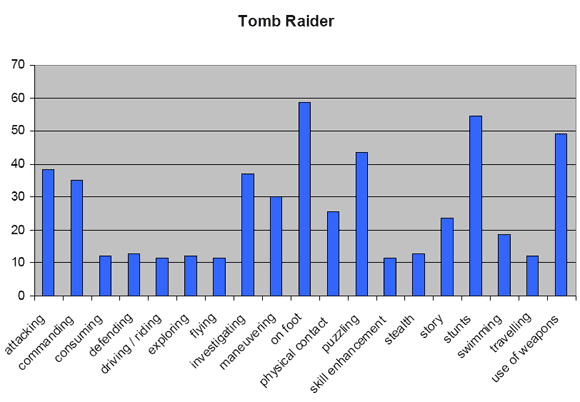

Let’s start by profiling the very first Tomb Raider game (figure 1). On the x-axis we have the activity groups that our analysis software found for this game. On the y axis we have the relative weighting calculated for that activity, also calculated by our software.

Of the forty eight activity groups that we profile games on we see that Tomb Raider scores significantly on nineteen, with strong scores for four activities in particular:

‘on foot’

‘stunts’

‘use of weapons’

‘puzzling’

These four higher weighted activities give a good picture of the main activities you undertake in the game. We then see that ‘attacking’, ‘investigating’, ‘commanding’ and ‘manoeuvring’ also score highly.

Figure 1, the activity profile for the first Tomb Raider

There is then a series of eight activities of lesser importance but which are none the less important to the overall gameplay experience of the first Tomb Raider.

Appendix A gives a listing of all the Tomb Raider games with platforms, publisher, developer and so on; also drawn from Strange Agency’s database.

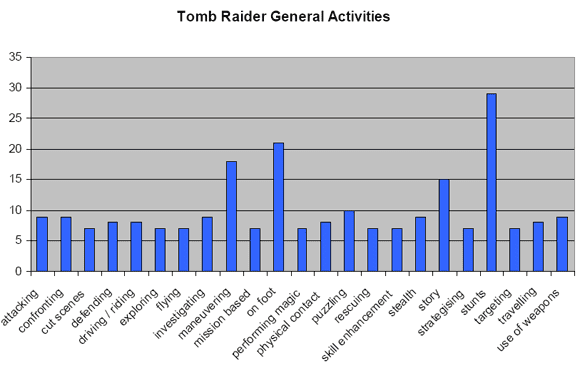

If we profile all of these games independently we can then construct an average profile for the whole series and compare it with the very first game (see figure 2). One thing we immediately notice is that, while the set of activities is basically the same, as we would expect, they have been reordered so that the top four activities are now:

‘stunts’

‘on foot’

‘manoeuvring’

‘story’

So ‘stunts’ have moved up somewhat and that is not surprising because Tomb Raider became famous for the stunts Lara could perform. We also see that ‘story’ has made a dramatic leap up the activity profile. There are twenty three activities represented overall but that after the first four the profile goes quite flat with all the rest having about equal importance. Conversely, the first Tomb Raider game had eleven activities in descending order of importance before the profile flattens out.

Figure 2, an averaged profile for the whole Tomb Raider franchise

This means that as the franchise developed the first four activities became central to the overall gameplay while a whole series of other activities were present but less important. The player is principally concerned with a small set of activities but from time to time a whole range of others offer themselves up making for a diverse pattern of gameplay.

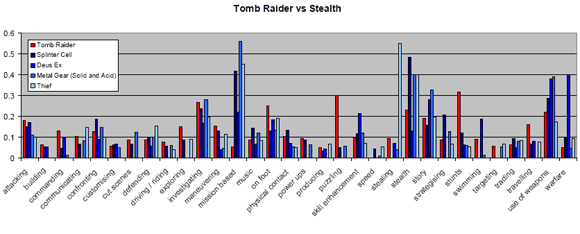

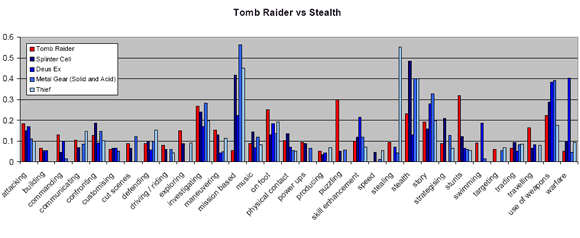

One of the features of the mid to late nineteen nineties was the creation of the sneak-em-up genre by combining FPS and adventure. We chose four stealth games: Splinter Cell, Deus Ex, Metal Gear (Solid and Acid) and Thief and compared their individual profiles. We also compared them against the average profile for the Tomb Raider franchise. The results, quite a complex histogram, can be seen in figure 3 below and full page in Appendix B.

Let’s see what the chart tells us.

If we take the four stealth games first, we see they present a pretty coherent picture. Not exactly the same of course. One of the characteristics of game genres, and indeed genres for films and so on, is that for a game to fit the genre it has to be in many ways the same as the other games in the genre but it also has to be different. We see this in the activity profiles. There is a strong pattern of similarity but with each game differing on some of the activity profiles. For instance, if we look at the activity ‘stealing’ we see that Thief scores heavily on this while Splinter Cell doesn’t score at all. Yet in most other respects the two games are remarkably similar. So in a very clear way we see the way a game both fits its genre and finds an edge within it.

Figure 3, Tomb Raider and Stealth game profiles

Figure 3, Tomb Raider and Stealth game profiles

Thief, as its name suggests, is a stealth game with a great emphasis on stealing. If we correlate such activity profiles we can begin to pick out USPs and KSPs. There are other such edges revealed in the same chart. Deus Ex scores very strongly on warfare whereas the other stealth games do not. As with Thief, Deus Ex follows the stealth genre profile quite closely with a few minor exceptions. Interestingly, it has the lowest score on stealth, lower than Tomb Raider in actual fact. This is perhaps due to the emphasis placed on the action.

Now let’s see how Tomb Raider, red on the chart, shapes up as a stealth game. For most of its activities the game follows the scores of the four stealth games very closely indeed, except for the activities: mission based, puzzling, stunts and travelling. The latter is a minor activity so we’ll concentrate on the other three in this short report.

First of all, Tomb Raider is not mission based but level based. The player follows levels by solving puzzles as Lara comes to them rather than having a task set and then trying to find out how to complete it. Tomb Raider, as we already noted, involves a great deal of puzzle solving in order to complete levels. Finally, we can note that Tomb Raider scores very heavily on stunts compared to the four stealth games. We already noted that the game was famous for the stunts Lara performs for us, which is a legacy of the traditional platform genre.

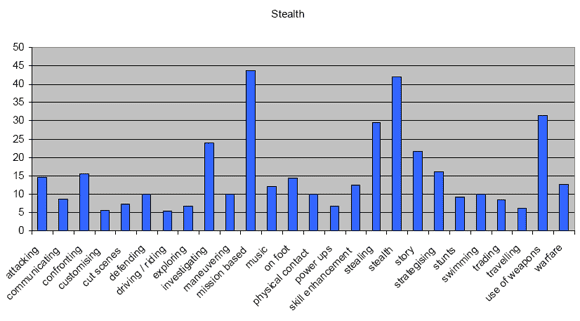

Figure 4, a calculated genre for the four stealth games

So Tomb Raider has many stealth-type attributes but diverges much more from the others in certain key respects. So much so that we would be wrong to say it is actually a stealth game with a strong edge. In a real sense it is an adventure game with a strong stealth component. The Tomb Raider ‘genre’ is out on its own.

This paper has a number of outcomes for developers. First of all it demonstrates the way in which genre profiling can be used to identify key characteristics of individual games. Even for a brand as familiar as Tomb Raider it is interesting to see what kind of activity profile and mix of activity the game offers. It is also interesting to see what activities dominate gameplay but also the range of other activities which, while less prominent, serve to complete the picture.

It is also possible to see that the Tomb Raider profile has changed over the years. If we looked at the profiles for all versions of the game on all platforms we can also observe interesting changes and developments. But that will be left for a future STAR.

Secondly the report demonstrates the way such profiles can be used to calculate profiles for standard industry genres, sub-genres and indeed other groups of games with some common characteristics. A developer who specialises in stealth games for instance, would have a great deal of knowledge about how their games are put together and, maybe through playing other such games, would also know a good deal about what their competitors were doing. But the ability to view the genre from a quantifiable point of view can only add to their creative design decisions. For instance it gives a measurable indication of just how much a new game concept could deviate from the genre yet still fall within it.

Also valuable is the ability to inspect an activity profile for a lesser known or unknown game and instantly get an idea of its characteristics.

Thirdly this STAR demonstrates the way in which game profiles can be compared against each other and against profiles for whole genres. We see clearly how individual games from a given genre are the same and yet different to each other and their genre as a whole. We also see how a game can borrow from a given genre and adapt it with subtle changes to produce a similar gameplay experience that is perceived as very different by reviewers and players alike.

Major Tomb Raider Titles

GameID | Platform | Release Date | Developer | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tomb Raider The Angel of Darkness | PC | 01/07/2003 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider The Angel of Darkness | PS2 | 20/06/2003 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Lara Croft Tomb Raider The Prophecy | GameBoy | 12/11/2002 | Ubisoft Milan | Ubisoft |

Tomb Raider The Prophecy | GameBoy | 12/11/2002 | Ubisoft Milan | Ubisoft |

Tomb Raider Curse of the Sword | GameBoy | 01/07/2001 | CORE Design | Activision |

Tomb Raider Chronicles | PC | 21/11/2000 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider Chronicles | Dreamcast | 19/11/2000 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider The Last Revelation | Dreamcast | 25/03/2000 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider | GameBoy | 01/01/2000 | CORE Design | THQ |

Tomb Raider Chronicles | PS | 01/01/2000 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider The Last Revelation | PS | 22/11/1999 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider The Last Revelation | PC | 31/10/1999 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider III Adventures of Lara Croft | PC | 21/11/1998 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider III Adventures of Lara Croft | PS | 21/11/1998 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider II | PC | 31/10/1997 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider II | PS | 01/01/1997 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider | PC | 31/10/1996 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Tomb Raider | PS | 01/01/1996 | CORE Design | Eidos Interactive |

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like