Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

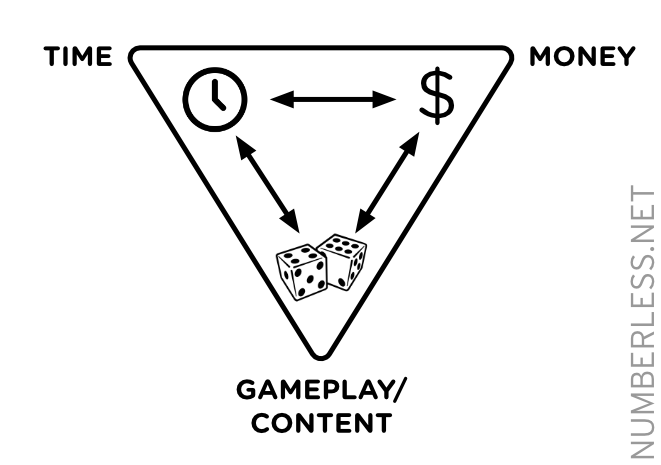

When designing microtransactions in games, we can easily forget the players' capacity to weigh their choices based on the perceived value. This post breaks down the transactional relationship between a player's time, money, and access to game content.

We often take for granted the player’s ability to intuitively understand transactional moments in free-to-play games. For a player, these transactional moments occur whenever they are evaluating the exchange between their time, real money, and access to gameplay or content.

We often take for granted the player’s ability to intuitively understand transactional moments in free-to-play games. For a player, these transactional moments occur whenever they are evaluating the exchange between their time, real money, and access to gameplay or content.

This is important for building and tuning monetization through microtransactions, as well as through ad revenue.

If the player is asked to spend money for something they can earn in the game, they will evaluate whether the amount asked for is fair, given the amount of time it would take to otherwise acquire that content. They will also evaluate whether the content is worth it to them for the amount being asked.

If the player is asked to spend money on content that can’t otherwise be earned in the game, they will determine the value of the content, and the value of the game itself (“is this game worth spending x amount on?”).

But transactional moments are not limited to real money transactions. Anytime an exchange is proposed (be it time for content, real money for time, or real money for content), it is a transaction, even when money is not directly involved.

As I said, these value propositions are important to understand not just for microtransactions, but for ad revenue as well. If a player is asked to watch a video ad for access to content or gameplay, they will evaluate whether the reward for watching the video is worth the 15 or 30 seconds the content will take to “earn” by viewing.

The player will also consider the value of content earned through watching video ads (time for content), versus the same or similar content purchased through microtransactions (money for content). Being overly generous with video rewards can negatively impact monetization, while not giving fair value for the player’s time will reduce their engagement with video ads, negatively impacting ad revenue.

Alternately, if the game has forced video ads (unskippable videos embedded within the game flow), the player will also evaluate whether continued engagement with the game is worth the amount of time lost to advertisements. If, for example, a player has to watch a 30-second ad every time before engaging in gameplay that lasts roughly two minutes (and yes, I've seen a developer do that), that player will determine for themselves whether the ratio of time-to-gameplay constitutes fair value, and justifies further engagement with the game itself.

Moral of the story: your decisions around ad revenue can negatively impact both retention and monetization, so step wisely.

Just as “fun” is a subjective assessment specific to every player, “fair value” will also vary depending on the degree of value a player places on the game itself. User testing both gameplay and transactional moments can play a big role in determining the proper tuning for the greatest success; you can’t win by spreadsheets alone.

Even in pre-production, it’s worth considering transactional moments when building the game’s systems. Crossy Road (which monetizes incredibly well across both MTX and ad revenue), provides generous value for ad impressions, but can afford to do so by having no overlap with the game’s MTX content — video ads reward the player with coins, which they can only otherwise earn through gameplay and not MTX.

For more on Crossy Road’s history and successful experiments in value propositions, check out the developers' 2015 GDC talk.

One final note on fair value: I believe there is a significant difference in the value proposition for content that will only benefit the player, and content that will benefit multiple players, particularly in a social context.

Consider this example: A player is asked to spend $2.99 on content in a single-player game. Later that day, the player has friends over playing a party game, and is presented with an opportunity to unlock more multiplayer content for $2.99.

Are these two value propositions the same? The one grants additional content exclusively to the player, while the other will add content to a game being enjoyed by a group of friends, providing further entertainment and social experience.

Imagine you're the player. Which $2.99 transaction is easier to make?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like