Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Video games today capture vast amounts of player data that can be used in ways that improve gameplay or threaten player privacy. We recommend developers be considerate of player expectations in order to minimize "creepy" behavior and avoid privacy issues.

Joseph Newman and Joseph Jerome are lawyers that focus on privacy and technology at the Future of Privacy Forum. This article is a condensed version of a larger piece on video games and privacy entitled “Press Start To Track: Privacy And The New Questions Posed By Modern Videogame Technology.” The full version of the paper will be published by the American Intellectual Property Law Association’s Quarterly Journal later this year.

While it sometimes feels like it doesn’t take much to incite a firestorm among the gaming community these days, nothing brings out the pitchforks quite like a good-ol’-fashioned privacy scandal.

People freaked out about Microsoft’s proposed “always on” Kinect 2.0 camera, calling it creepy as it watched them “like a cross between fictional serial killer Buffalo Bill, an actual serial killer, and that robot from The Black Hole.” Gabe Newell had to fend off accusations that Steam scanned its players’ web browsing logs. And as you may have heard, the NSA is intensely concerned with how you play Angry Birds.

It’s easy to feel lost when discussing privacy issues in games. What are developers doing with all their data? And what, really, is at stake?

Through a combination of sensors and integration with other data sources, developers are now capable of collecting a veritable treasure trove of player data. We’re talking about stuff like a player’s physical characteristics (including skeletal and facial features, body movement and voice data), location and nearby surroundings, biometric info, social network information, and – perhaps most interestingly – the player’s detailed and robust psychological profile.

Analyzing a player’s mind isn’t just about measuring their skills. Huge advancements in the field of psychography (quantifying psychological characteristics) reveal more about players’ personalities than ever before: from their temperament to their leadership skills; from their greatest fears to their political leanings. Also – because of course – their likelihood of sticking with a game and their willingness to spend money on it.

The ability to collect game data post-release has fundamentally changed the nature of the gaming conversation. Most developers are not merely releasing games into the wild and forgetting about them; rather, they are acting as collectors and stewards of massive quantities of player data. And for the most part, it’s been great: player data drives new in-game features, creates new methods of monetization and promotion, helps regulate virtual economies, detect fraud, link with social media, guide resource allocation in development, and ultimately keep players engaged with content that adapts to their individual preferences.

Some say that player segmentation is already the “next big thing” in game analytics. For instance, DeltaDNA’s algorithms use a player’s in-game actions to predict their “revenue potential” as well as how likely they are to promote the game to others on social networks. Players who are “scored” as likely to spend money are likely to receive offers that will differ from those players that are at risk of leaving the game.

Why do they do this? It’s simple: developers need to quickly and effectively target users that are likely to spend money on their game. After all, only 0.15 percent of mobile gamers account for 50 percent of all in-game revenue. On the other hand, price discrimination has some serious ethical (and legal!) problems; nobody likes it when a game stops being about the player’s skill and turns into a money squeeze.

Moreover, lots of people find certain types of data use “creepy.” We know that Candy Crush collects player data and rejiggers levels if they are too hard for most players. Sure, it’s great that the games are more engaging, and King swears “there’s no evil scheme” behind Candy Crush’s addictive nature. But is it unethical to use a player’s data to manipulative them into playing longer (and spending more)? How long until the psychological techniques used by casinos to keep players addicted to video slots become commonplace in casual games?

Players are also concerned about who their data gets shared with. Sure, we understand that our gameplay data might be shared with advertisers or used in cross-promotions. But what about sharing our gameplay habits with our employers? Developer Knack uses data gleaned from its specially designed video games to “suss out human potential,” specifically learning about “your creativity, your persistence, your capacity to learn quickly from mistakes, your ability to prioritize, and even your social intelligence and personality.” Sure, maybe you don’t think you have anything to hide, and that all this privacy stuff doesn’t matter to you. Still, we’d wager that even the most permissive player might be concerned if his or her gaming habits could reveal his or her online conversations, or physical and mental well-being to a complete stranger. (And let’s not forget that when games collect data it could always end up in the hands of hackers or, you know, the NSA.)

Mining player data has incredible potential to benefit both developers and players alike. Nevertheless, as mentioned before, gamers are quick to pull out the pitchforks when companies start acting “creepy” with their data. And if players do not trust you to handle their data, they will not invest in your product.

Rather than passing a general privacy law, the United States’ approach has been to pass a patchwork of laws, agreements, and regulations that govern how specific types of data are used. These regulations include (but are not limited to) the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), and the Federal Trade Commission’s ability to police “unfair or deceptive” trade practices. (For a more in-depth analysis of the legal issues at play, be sure to read the authors’ full version of this piece in the AIPLA Quarterly Journal, to be published later this year.) The concept of privacy is “highly elastic” and means different things to different people. So how do we deal with privacy issues in games?

The privacy traditionalist might raise his hand and say, “just make the player agree to the tracking in a waiver before they start playing! If they don’t want to be tracked, they can just opt out!” It’s a logical idea, but this so-called “notice and choice” privacy framework is increasingly impractical in light of new technology. Former FTC Chairman Jon Liebowitz has conceded that “notice and choice” hasn’t “worked quite as well as we would like:” the vast majority of consumers don’t read privacy policies and don’t make educated choices about the policies they agree to.

Moreover, increased transparency about data use might actually ruin some gaming experiences. For example: Konami’s Metal Gear Solid famously broke the fourth wall when boss character Psycho Mantis “read the mind” of the player (or more accurately, read the contents of the player’s memory card). Had Metal Gear Solid announced it intended to scan the player’s other save files and asked for permission to do so, the surprise of Psycho Mantis’s “psychic demonstration” – an enjoyable and ultimately privacy-benign moment – would have been ruined.

So, maybe the solution is to just weigh the benefits and harms on a case-by-case basis? Developer Nicholas Nygren argues that developers should avoid collecting and using data on players “unless such monitoring has an obvious benefit for the player experience.” But what is an “obvious benefit” for players? Many current uses of data, such as mining user data for quality assurance testing, provide a benefit primarily to the game developer (for example, using data to find and eradicate glitches). However, the player receives a benefit in the form of a game with fewer bugs. Does mining for this purpose provide an “obvious” benefit? Likewise, highly targeted advertising is often criticized as invasive and unsettling, but one often can argue that increased personalization “obviously” benefits the recipient of the targeted offer.

The benefits and harms associated with data use are often abstract and cannot be objectively weighed against one another to create any helpful conclusions or guidance. The challenge going forward therefore ought not to be framed as a balancing of benefits and harms.

Rather, it’s about minimizing unpleasant surprises.

Put simply: don’t piss off your users, and don’t be creepy. Easier said than done, right? Well, in order to avoid creepiness, you need to be aware of player expectations and continuously adapt to them. So, what are these expectations? Well, here are a few we’ve come up with.

Players generally expect they will receive the same offers as all other players, and that their individual psychographic profile will not be used to surreptitiously “mark” them to receive different offers than their friends without their informed consent. This expectation also means developers should not use a player's data to make the game make a game unplayable without purchasing powerups. (Note that a developer that deceptively withholds the fact that individualized psychographic data is being used to alter pricing in its game may additionally face enforcement action by the FTC.)

Players would be upset if they discovered that, unbeknownst to them during the course of purchasing a game, they received a substantially different gameplay experience than their peers based on pre-existing data about the player’s gender, age, physical location, health, psychographic profile, etc. (Note that in many cases, your data use can be described as a “feature” designed to create a more personalized experience for the user.)

It is common in the industry for developers build a “digital shoebox” with all the data they can grab, even though don’t know exactly what to do with it yet or what value they would get from it. That’s a bad idea. It is in the developer’s best interest not to hold data that won’t be used, because doing so automatically reduces the risk that the data might be lost or stolen.

Developers should also establish rules about their company’s data retention practices. Developers should define separate retention periods for both aggregated data and data tied to an individual player profile. While there is no single retention duration that will be appropriate for every game or use, one reasonable practice would be to delete or de-identify individualized player data one year after the player plays the game that collected the data.

Aggregated or de-identified data – “[x] number of players do [y]” are statistics that provide valuable info without tying data to an individual user. In fact, by “de-identifying” data, you can avoid many privacy concerns. But there is still a risk that others might be able to re-identify the individuals using a variety of techniques. “Perfectly de-identified” data may not be possible or feasible – nonetheless, players expect that up-to-date technical, legal, and administrative safeguards to be in place.

Not all games are advertised as having offline play. However, for games that do advertise a “single-player,” unconnected experience, players expect that they will be able to experience the full extent of the game’s offline features without significant difficulty even if they do not agree to the developers’ uses of player data.

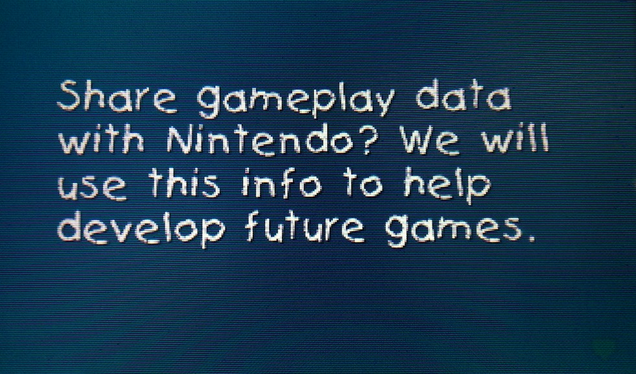

Nintendo’s new games handle this well. When first starting Yoshi’s New Island, the game prompts the player with a dialogue box: “Share gameplay data with Nintendo? We will use this info to help develop future games.” If the player selects “No,” the game continues with no noticeable effects. On the other end of the spectrum, there are games that make it really frustrating to play offline, despite advertising single-player features.

(The one exception to this opt-out expectation relates to digital rights management (DRM), but that’s a whole other can of worms.)

Players expect transparency from developers who alter their privacy policies, including prominent, plain-language descriptions of how policies are set to change. Standardized icons or accessible language can also be used to clearly communicate changes to players. Although the FTC currently requires that all “material” changes to a privacy policy that retroactively affect consumers require notice and consent, developers should nonetheless ask for consent before making any substantial prospective changes to their policies, in order to avoid negative publicity and diminishing player trust.

Certain types of data (such as health data, financial data, or education data) are already considered to be particularly sensitive and therefore “off limits” for onward transfer without the user’s specific and well-informed consent. The psychological profiling techniques made possible through new game technology necessarily call for new categories of data that qualify as “sensitive.” These categories should include information about (1) the player’s mental health or intelligence, (2) the player’s emotional state or states, and (3) the player’s spending habits (i.e., how likely they are to pay to progress in a game).

Players expect that if they experience a game on multiple devices, their privacy preferences will be honored across all similarly branded devices. Players also expect that if they upgrade to a new console that imports the same account, their privacy settings will also be imported. Whenever feasible, systems should also be put in place to ensure that privacy settings are automatically integrated across all devices, not simply the newest device.

This is already the practice on most platforms. In a game with online and offline features, social media participation should never be mandatory to access offline content. Moreover, players should be able to unlink their social media account at any time while retaining their in-game progress.

Most privacy controls are ideally provided by the device platform, rather than within the games themselves. However, if a developer plans to use data in a way not covered by the platform’s policies, players expect that they will be given accessible privacy management tools within the game itself to control the new data use. Moreover, it should be as quick to disable a setting as it was to enable it.

For businesses today, it is sometimes said that “data is the new oil.” By gathering and refining “crude” player data into metrics, video game developers can create seemingly endless amounts of new, exciting features both within the games themselves and in the world at large. Nevertheless, both oil and data can produce real damage to society if collected and used haphazardly. Game developers should keep in mind that unlocking the benefit of data while preserving player trust requires appropriate consideration, safeguards, and respect for players’ privacy expectations.

The expectations we’ve outlined here represent a collection of baseline privacy expectations developers should consider before incorporating player data into their game development process. It is the responsibility of developers to understand and adapt to their players’ evolving privacy expectations in order to reduce unwanted surprises. This will ensure that players trust developers, and are willing to invest in their services.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like