Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Sunset was their final game, and Tale of Tales is no more. But what really happened?

(This post also appeared on The Astronauts' website.)

In a month, Sunset sold only four thousand copies, and Tale of Tales decided it was their final game.

The industry sent a lot of words of support, and mourned the death of the studio (1,2,3).

I will join the mourning in a second. But I also think that Sunset is a great case study and there are lessons to be learned from its creative and marketing process.

I wasn’t sure if this was the right moment for an article like this. De mortuis nil nisi bonum, of the dead speak well or not at all. But since the studio is not exactly dead, on the contrary, and as such will continue their art war, just outside of video games, I figured this story might be worth telling after all.

There’s going to be a bit of tough love here for Tale of Tales, but that does not change the fact I deeply regret they are leaving this particular industry.

With the exception of The Graveyard, a super-short vignette game, personally I never fully enjoyed anything that Tale of Tales produced. At the same time, their games were always inspiring to me. I would even go as far as saying they were eye-opening.

I know this sounds like a paradox, but that’s how creators function. Our thoughts are provoked and our ideas are inspired by various sources. Sometimes, we do not consume stuff to enjoy, we consume it to get our creative juices flowing.

Take The Path (2009, above) for example. Many things did not work for me in this game, and I am being the zen master of courtesy here. But at the same time …it was one of the inspirations behind The Vanishing of Ethan Carter.

When you start The Path, all you get is “Go to Grandmother’s house and stay on the path.” If you do that, you can reach the end in just a couple of minutes (and that’s just because moving in the game is extremely slow). But the game knows this, anticipates your behavior. It waits for you to get off the obvious path on your second playthrough. And then you do just that, and you start exploring, and things happen.

It’s not the heavy-handed metaphor of going off the beaten path that worked for me here. It’s the idea that the players must invest themselves in the game on their own, without the game offering them any extrinsic motivation. The world of The Path was just there, indifferent. And its exploration was not rewarded with extra ammo or completion points. It was the reward in and of itself.

I know these things are obvious now in 2015. But The Path was quite revolutionary in its approach at the time of its release. No wonder it inspired so many developers.

Or take The Graveyard, another Tale of Tales production. I wrote about it once myself, I loved everything about it, and happily paid five bucks for a five minutes long experience. I wasn’t the only one moved by it, of course. Did you know it inspired that powerful village scene in Naughty Dog’s Uncharted 2?

I even enjoyed moments of the super cryptic – at least for me – Bientôt l’été. When sitting on a bench near the sea I got an extremely powerful sense of presence, and you can see from the screenshot above, it was definitely not about the graphics. That feeling got me thinking heavily on how to achieve something similar in The Vanishing of Ethan Carter.

So yes, Tale of Tales influenced me as a designer, and did the same to many other creators. I cannot imagine any book on the history of the artful side of games not featuring this two person small Belgian studio.

Influential and inspiring does not mean commercially successful, though. I am not surprised. While inspiring for some, their games were often technically awful (unoptimized, with unfriendly UI), and most people simply found them boring. It seems like Tale of Tales survived through all these years mostly due to the governmental grants. When that ended, the studio decided to make their first commercial game, and that’s how Sunset was born.

Here is the puzzle. The game was technically and visually the best that Tale of Tales ever produced. It tried to tell a meaningful story and be a meaningful experience. The Kickstarter campaign for the game was a success. Tale of Tales hired people with connections in the industry to help them with the marketing. Some story-focused indie explorers like Gone Home sold hundreds of thousands of copies, so clearly there’s a market.

But no, a month after the release, Tale of Tales announced that the game sold only four thousand copies, and that’s actually including the Kickstarter sales.

So… What exactly happened?

Here is a list things that, in my opinion, contributed to the low sales of the game. All of these things make sense, I hope.

But then I will tell you why they didn’t matter that much in the end.

THE GAME IS NOT ENGAGING

I never fully bought into the idea that art must be “not fun”. But that little I did, it’s because there can be a purpose to the “not fun” part. The mind-numbingly long scenes in Tarkovsky’s Stalker are to put you into pseudo-hypnotic state the movie benefits from in the third act, and the rape in Irreversible annihilates your heart and mind in order to tell the harsh truth about the cruelty of indifferent Fates.

But I have never seen what purpose do the technical and design shortcomings of Tale of Tales games serve. It was mostly incompetence to me, not art.

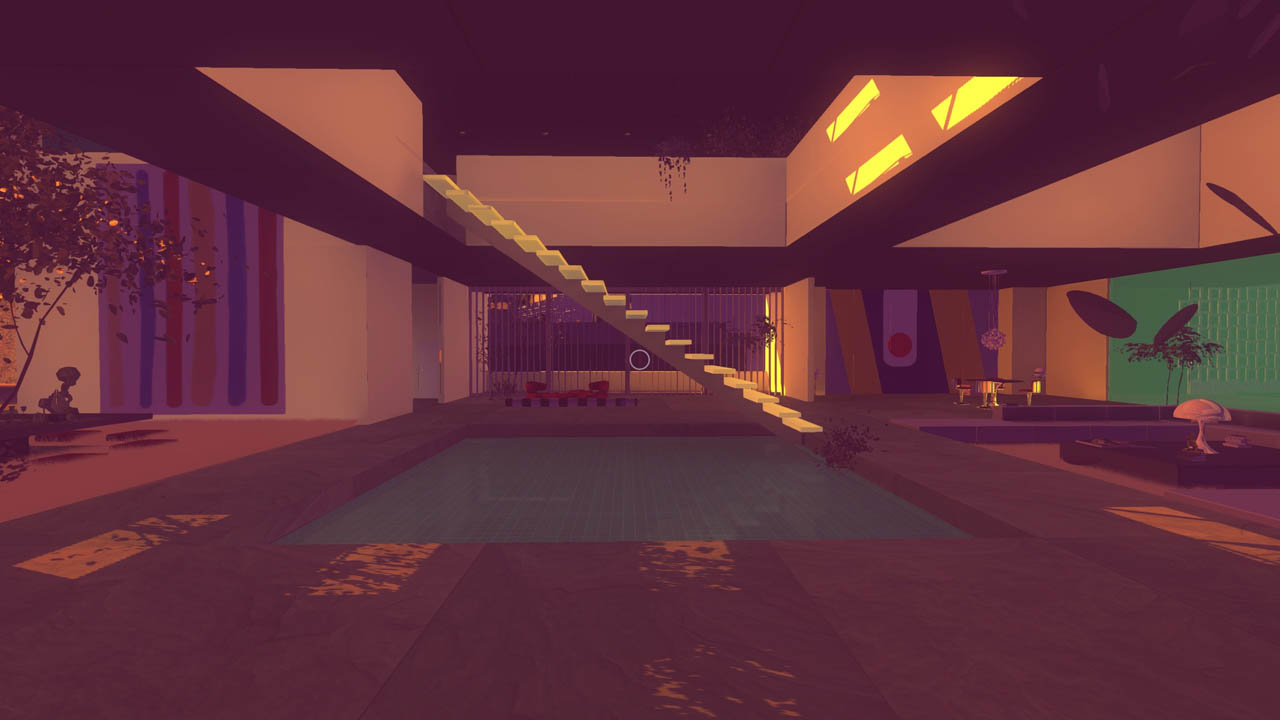

Sunset is no different. The core fantasy is not the worst I’ve seen, but the game quickly gets mechanical. Once you understand how the game works, you start optimizing that system, and each visit to the apartment is a boring scan of the all too familiar environment in search for the new activities.

One could make an argument that, well, this is what a cleaning lady’s life is like. But that’s why, if we can afford it, we avoid this activity and pay others to do the job.

More importantly, the game is not about that. Showing the mundane life of a cleaner is not the point of the game (check out Cart Life for that kind of experience). The game is completely about something else, and the cleaning is merely a pretext.

But with the way the game is structured around that “something else”, Sunset does not challenge anything other than your ability to stay awake. Its “not fun” parts serve no purpose.

Of course, some people did find Sunset enticing. Even though most reviews did not exactly praise Sunset, IGN gave it 8/10, after all. However, it is the case with literally every piece of art that one man’s boredom is another man’s excitement. It’s just that these groups are rarely equal.

TALE OF TALES DID NOT UNDERSTAND THE AUDIENCE

Tale of Tale claims this time they made a “game for gamers”. Sadly, all it shows is that they have no idea what that means. The studio added a FOV slider and a key/button to easily grab a screenshot, but that’s a very superficial way of thinking this is what makes a gamer’s game.

In their farewell, Tale of Tales describes Sunset’s focus on gamers as “conventional controls, three-act story, and well-defined activities”.

“Conventional controls” happened only to a certain degree. For example, I cannot access any menus with neither Start nor Back button on the gamepad – I have to use the keyboard. So they’re far from perfect.

More importantly, though, why on Earth is this a talking point? Conventional controls are conventional because they work. Using them removes the friction between the player and the avatar, and that is highly desirable. Advertising the fact that the game does not use a weird control scheme – which was indeed a problem with some earlier Tale of Tales games – is like being proud the font in a book is large enough to be readable.

Note that the consumption of other art is easy. If we are talking about things you physically need to do, reading a book is easy, watching a movie is easy, listening to music is easy. This allows people to focus on the message, not on the conveyor of that message. Weak control schemes get in the way of that in video games the same way a scratched CD gets in the way of a listening session.

The “three-act story” is not something video games should concern themselves with. Not even in the movie business the creators agree it’s the right structure, but in video games it simply makes no sense. The players dictate the pacing in Sunset, and three acts do not work well with that.

But the misunderstanding of what gamers really want and need is best visible in the last element, “well-defined activities”. It’s like the studio is oblivious to the fact that one of the most popular genres in the world is a survival sim, and there are no “well-defined activities” in Day Z. And there are no “well-defined activities” – a la checklist in Ubisoft’s open world games – in Minecraft’s most popular mode or in Garry’s Mod.

But even if we agreed that “well-defined activities” can help a game, the execution is simply wrong. It’s a relatively small apartment for a video game, and yet quite often I lost minutes in search of this or that checklist activity. At one point I had to “stamp a letter” …and I failed to do it, as I could never find it – and I searched the apartment for literally half an hour.

The “game for gamers” also features quite hefty hardware requirements. Looking the way it looks, it struggles on my GTX970 PC. With these visuals, I should get about a thousand frames per second, but sometimes I barely get twenty. I did set everything to “ultra” (or whatever it’s called), but still, we’re talking cartoon shapes and low poly objects here. Inside one apartment. When this:

…runs faster on my PC than this:

…something’s wrong.

The game suffers from other technical issues, too. I played a version after a few patches, a month after the release. And still sometimes the gamepad was “losing focus” and I could no longer look up and down (I found a workaround, but that’s not a real solution).

Speaking of looking up and down, this is what you do in this game a lot – especially looking down. It’s not surprising, as you’re cleaning an apartment and are mostly looking at things on the floor, tables, and chairs. But this is the maximum angle you can look down at:

As a result, in order to interact with an object, I often had to move far away from it to be able to catch it in my crosshair. And that’s just one of many examples of what went wrong with the basics of a proper user interface.

To sum it all up, Sunset suffers from technical issues and multiple objectively bad design decisions – oddly created by co-designing the game with a game journalist instead of an actual game developer. Not that this idea was inherently bad and this is not a jab at the journalist, we all do know quite a few writers that became successful game developers. But if you attempt your first commercial production and you want to consult someone, a proven game developer simply offers a higher chance of success, I believe.

THE REVOLUTION DEVOURED ITS CHILDREN

Probably not many gamers are aware of the term notgames, coined by Tale of Tales’ Michaël Samyn in 2010. The whole discussion around this artistic challenge – removing games from video games – was fascinating and inspiring. I feel like it made me a better game designer, as stripping games off their previously unquestioned features – and then putting them back together piece by piece – helped me understand them better.

We see the shrapnel of notgames and Tale of Tales’ creations in many modern games. Most gamers don’t notice it, and that’s fine, but it’s there. From the giraffe scene in The Last of Us to games that removed extrinsic motivation altogether – like whatever Telltale does now – we see today’s video games reaching for solutions rarely seen in video games before.

To be clear, Tale of Tales are not the inventors of this approach. For example, this year’s Her Story seems to be at least partially inspired by 1986’s Portal. So going outside of the unquestionable was a part of game making almost from the start. However, Tale of Tales was an important voice and I can easily consider them as influential pioneers.

I feel like today, the student surpassed the master, though. Many designers loudly express their love for Tale of Tales, and rightly so. But the lessons they’ve learned, they managed to put to better use, at least from the commercial point of view.

Gamers’ time is limited. Everybody on Steam has more games they could ever finish. Gamers’ money is limited. There’s something to buy every week, and if there isn’t, there’s always a sale going on somewhere. We live in an era in which you either need a five-star quality, or an idea that gets people fired up despite the product’s shortcomings (vide: the survival genre).

Sunset is neither. Sunset is a niche product that’s not particularly well executed.

People who are interested in the narrative experiences or experimental games have quite a few options these days. What Tale of Tales wanted – let’s be different and let’s be artsy – is happening. Tomorrow, Her Story gets released. In a few weeks, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Then we will have SOMA, Firewatch, and Tacoma. And I’m just talking these better-known indies, but, of course, there are many more.

I love narrative, thoughtful, quiet games and yet I can’t keep up. Mind: Path to Thalamus, The Old City: Leviathan, Kholat, and The Music Machine are all waiting for a day when I will finally “have the time”.

Tale of Tales inspired many, and the many carry the fire now, brighter than ever. And that is fantastic.

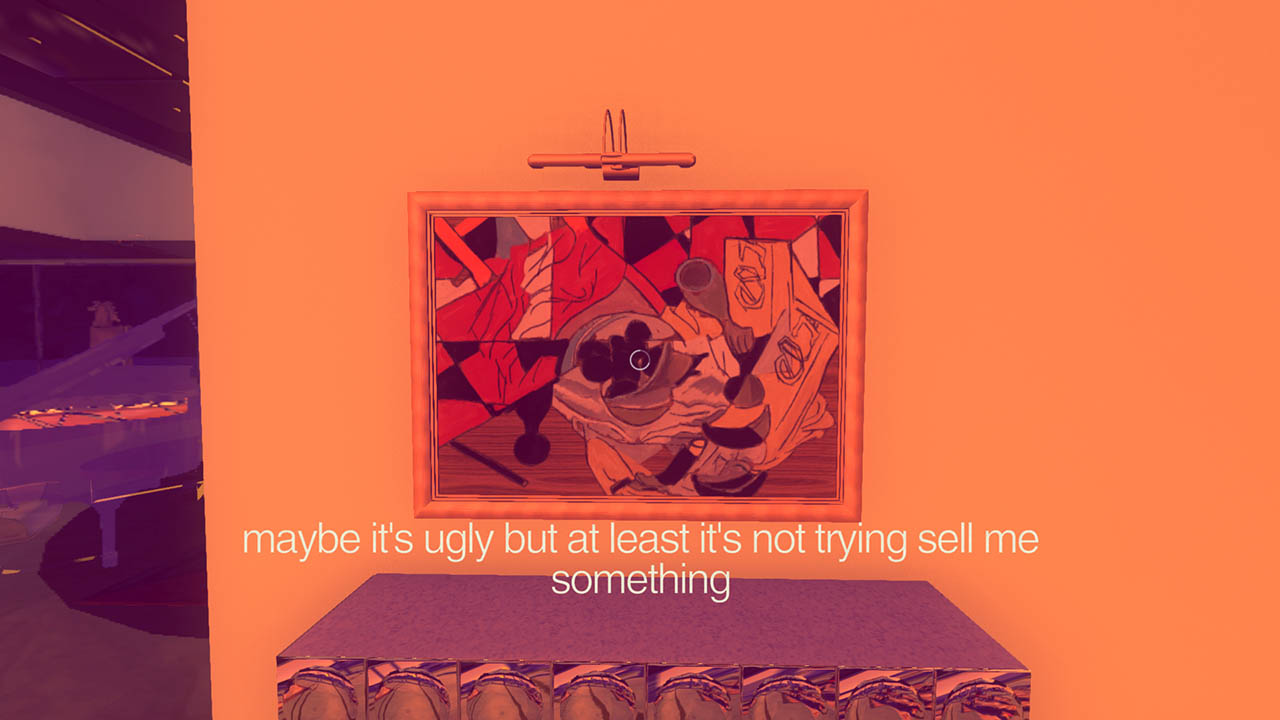

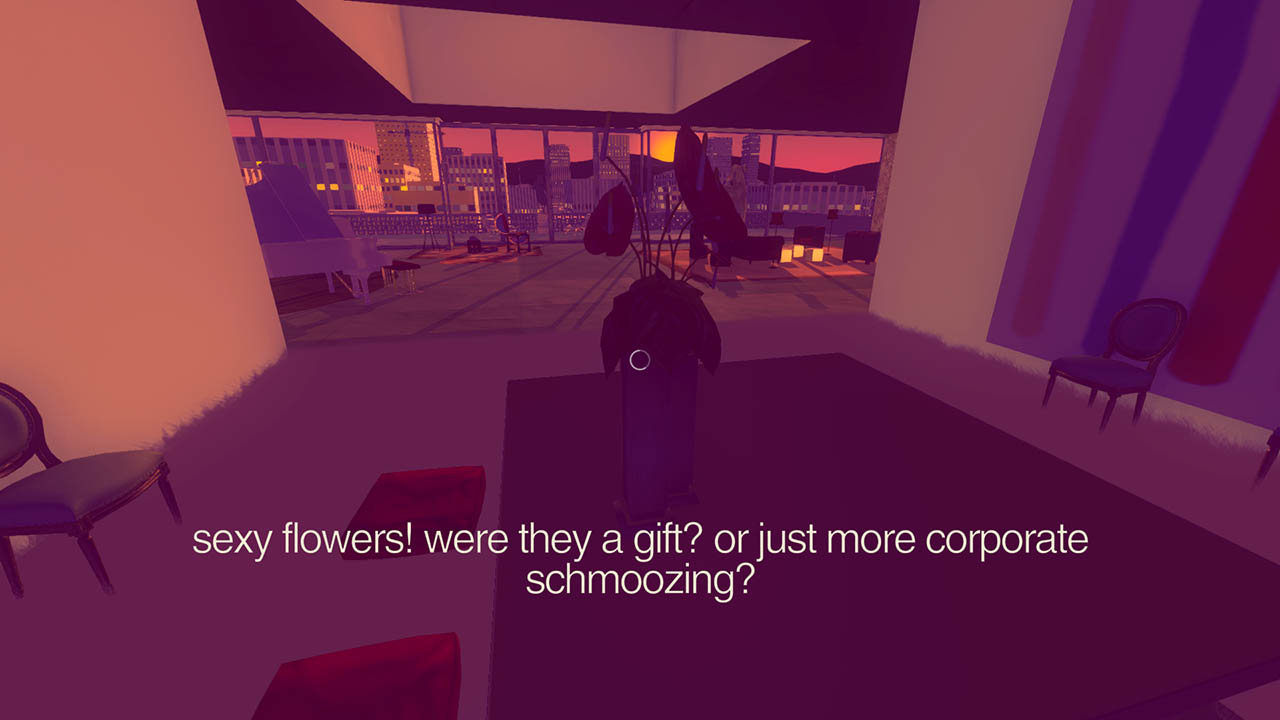

The problem is, Sunset had nothing profound, important or revealing to say. As the old saying goes, you’re only as good as your last haircut. The Sunset’s haircut isn’t particularly good. This is not the level of thought and reflection I expect from anyone over seventeen years old:

THE MARKETING WOES

SteamSpy reports that you can only have one launch. If it’s on Early Access, then that’s it, and when you move out of the Early Access, no one really cares. I feel it is nearly the same with Kickstarter. The excitement around the announcement of your crowd-funding campaign is usually much higher than during the actual release.

So was the case with Sunset, at least that is my experience. I proudly backed up the game on Kickstarter, but I didn’t know it was released until the Tale of Tales’ farewell stormed the Twitter.

I feel it had something to do with the game being released two days before The Witcher 3, the game that won endless “Most Anticipated” awards. Usually, you might not want to deprive your game of oxygen sucked out by either such juggernauts or big industry events like E3.

WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Did the above contribute to the low sales of Sunset? Sure. Everything matters.

But no, none of these things mattered that much in the end.

An unengaging, technically challenged game of questionable design and message sells four thousand copies.

But I know of a game that is technically capable, quite pretty, and fun to play. It was made by an indie developer that people already know about, and it also had a decent marketing presence. It’s called Juju and it sold only about one thousand copies. In half a year.

What does it tell us?

When you make something people do not want, no amount of marketing will sell your game.

Sunset might have tons of issues – I have barely scratched the surface – but it is definitely not a disaster. I can easily imagine some people enjoying it despite its problems. I’ve seen many less competent, barely functional, Unity asset shop games succeed on Steam.

So the thing is, Sunset just did not resonate.

Everybody is reaching for hypotheses now. It’s about the ludofundamentalist belief that games without challenge have no place in this industry. Or about a political war. Or about a controversial journalist in charge of the marketing. Or about the developers throwing a tantrum and claiming to hate the audience they tried to sell their product to.

None of that really matters. For any of the above, I can give you a bigger counter-example. A slow indie experiment that brought real money, or a developer who was openly an asshole and yet their game comfortably lingered in Steam’s Top 10.

But look, you have two options when you make art you want to be commercially successful.

One is to carefully study your audience. This is not to stop you from telling the story you want to tell, this is to let you understand how to communicate that story to them.

Two is to do your own thing and see what happens.

If option number one is your thing, you need to make sure you really understand what you’re doing. Otherwise, you’re “How do you do, fellow kids?” Steve Buscemi meme. But even if you do everything right, remember that nobody knows anything in movies, and that art form is well over a hundred years old. And obviously things are even worse in games, and that’s why when a big studio strikes gold, they keep producing sequels basically forever.

But if two is your thing, you must be prepared that no one is obliged to give the slightest of fucks.

So with those two options in mind, what happens when the game does not resonate and is not exactly a technical and design masterpiece?

Usually, you sell nothing and the only people playing your game on Steam are your friends and family. But sometimes, only sometimes, you get lucky, and you miraculously sell four thousand copies in a month. Add two thousand drama bonus.

And that’s what happened. Nothing else.

When I was preparing for this article, I read all what the hardcore had to say, and sure, there are some truths there. But I also analyzed what the rest of the gamers – ones that play games but are not active gaming commenters – were communicating. And they all said: “well, too bad, but, to be honest, the game did not look that interesting.”

That’s it, that’s the whole secret. “That happens sometimes,” Jim Sterling noted.

I am torn on how to end this post. I am puzzled by Tale of Tales’ reaction to Sunset’s failure. If you want your art to challenge the status quo, it’s a bit odd to expect the status quo to care. Leaving the art form just because the status quo was not moved by your first commercial attempt is even odder.

Sunset’s struggle it’s not the gamers’ fault. We can’t be talking about the failure of Sunset as if gamers refuse games as art that challenges them. Papers, Please, or This War of Mine, or Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons – all enjoyed spectacular commercial success and had something meaningful to say while demanding a lot from the players and often making them uncomfortable and struggling.

On the other hand, Tale of Tales are veterans of this industry, and even though they may have never been commercially successful, there is a reason why it’s them – among literally thousands of otherwise completely forgotten indie developers in history – who we are devoting so much attention to these last couple of days.

And this is why I regret they are going away, even if this is probably the right thing to do for them and they may find joy and success elsewhere faster than in here. I wish them so, and I thank them for everything they’ve done in the past. Good luck, Auriea & Michaël.

Meanwhile, give Sunset a chance and see for yourself if that might be something worth exploring. I criticized it a lot in this piece, but remember it did find some audience that liked it quite strongly.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like