Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

When I say the word "marketing", no doubt your mind is flooded with images of sleezy skags in suits talking about how transmedia synergies are really hot with the teen male demo. But here's the question: what IS marketing? Do you know? Do you really know?

Ahhhh, marketing. Few professions are as maligned as marketing. When I say the word "marketing", no doubt your mind is flooded with images of sleezy skags in suits talking about how transmedia synergies are really hot with the teen male demo. Nobody could say it better than Bill Hicks:

But here's the question: what IS marketing? Do you know? Do you really know? I'm going to go out on a limb and guess that if you absolutely, fundamentally hate marketing folks without reservation, you probably don't actually know what marketing is. Or, rather, what it's supposed to be. I'm a student at a graduate school that made its reputation on marketing, and I didn't actually know what marketing was supposed to be until I took a marketing class. Marketing isn't just advertising. It isn't just focus groups and lowest common denominator bullshit.

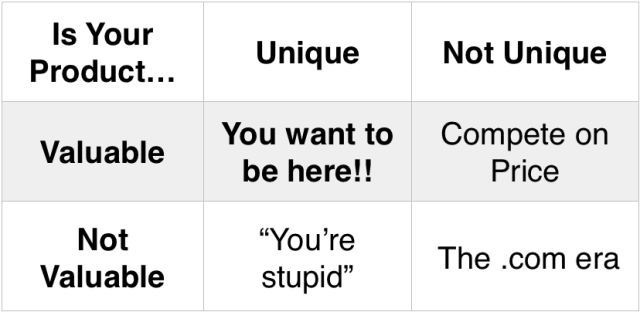

Here's how marketing is supposed to work, using an example Guy Kawasaki makes in every lecture of his I've watched on YouTube:

-"You're stupid" is Kawasaki's summary, not mine.

-"You're stupid" is Kawasaki's summary, not mine.

To put it in terms of marketing:

-My summary.

-My summary.

Here's what marketing is supposed to be: marketing is the profession of creating value for your customers, your collaborators, and your company. In other words, how do we make something that people want to buy, that our collaborators want to help us sell, and that turns a profit. That's it. That's what marketing is. Design an exciting, valuable product, from cradle to grave. Now, seriously, is that really that evil? Not if you accept that the games industry is a business and it needs to be profitable to be sustainable. And marketing is just the process of making products profitable.

Now lets talk about what marketing - or rather good marketing - isn't.

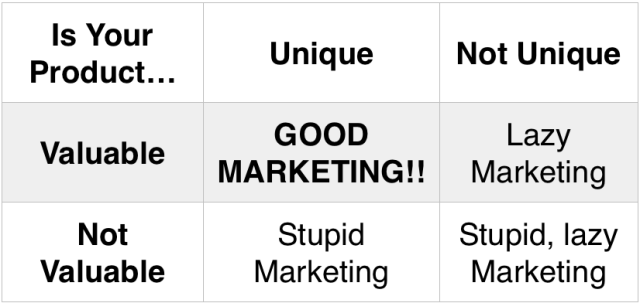

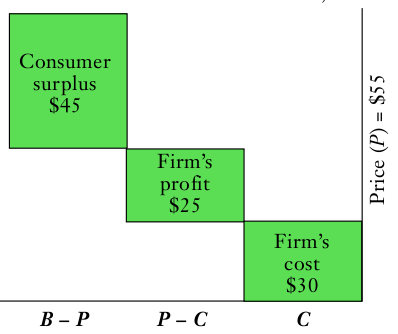

Good Marketing Isn't Making the Same Product as Everyone Else Because it's The New Hotness

One of the most basic lessons you learn in business school, a lesson that gets drilled into your head throughout your core classes, is that making the same thing your competitor is making means you have to compete on surplus. The difference between the average per-unit cost it takes to produce a product (C) and the per-unit price you charge for it (P) is the "producer surplus". The difference between the price and what the product is worth to the consumer, his maximum willingness to pay (B), is called the "consumer surplus". If you're making the same product as your competitor, the customer now has two equivalent products to pick from, reducing his B for each. To get the sale, you have to provide more surplus and capture less for yourself, which means either a lower price than the competition (which tends to provoke a price war) or more value (and a higher average cost) for the same price. Either reduces the surplus you are able to capture. In the video games industry, this phenomenon manifests as feature arms-races between similar products, resulting in things like seemingly superfluous game modes, content for the sake of content, Hollywood actors, or a general lack of focus in a game's design.

*Image taken from Besanko, David, Economics of Strategy, 6th Edition (Page 299).

*Image taken from Besanko, David, Economics of Strategy, 6th Edition (Page 299).

For my fellow developers, this phenomenon has a more sinister consequence: crunch. If you're making a shooter, and you want to compete in a market crowded with shooters, you need the most badass feature set and the most immaculate level of polish. And you don't want to add development time - that would just jack up your average cost and make it harder to turn a profit. So...guess who's sleeping at the office from now until we go gold?*

The games industry is notorious for the fast-follow: "Hey, those guys made stupid money with Brotherhood of Valor Battle Duty Craft. Gimme one of them!" Yeah, they made money because they found a market need that no one was serving. Now they're serving it. If you want a piece of that action, you need to steal it away from them, so get ready to blow the ass out of your budget with some combination of feature creep, celebrity actors, media blowout events, and paying websites to rebrand their homepages.

However, if you have a marketing department that thinks strategically, and that takes your competitors and the overall industry context into account when creating value for your customers, collaborators and companyº, you can come up with products that avoid that trap.

Good Marketing Isn't Targeting a Product at Everyone

There's a great quote by Bill Cosby: "I don't know the key to success, but the key to failure is trying to please everyone." You know where I heard that quote? In my marketing class. It was even in my friggin text book, for pete's sake.

Making a mass-market, lowest common denominator product is not what a good marketing department is supposed to do. A good marketing department is supposed to avoid the death by a thousand cuts trap of saying "Yeah but if we just jammed this one additional feature in, we could capture market segment X".

A good marketing department is supposed to divide a market up into logical segments and then:

A) figure what need(s) those segments have and then find/develop products that solve those needs.

OR...

B) take an existing product and match it with or adapt it to a segment's needs.

The marketing department is then supposed to look at that market, decide how much revenue potential it has, and use that number to set a budget for the product so that it can be profitable. That's how you make a product that creates value for the customer (it's worth the price), creates value to your collaborators (their margins will be large enough to make collaboration worthwhile) and creates value for your company (you make money). That's how seemingly niche games like Dark Souls and Payday 2 can be well regarded and profitable while more mass-market games like Resident Evil 6 can fail to do either.

A focused product can provide a lot of value to a target segment because it can be better refined to suit that segment's needs. To the members of your target segment, if your product actually solves their need(s), they will have a higher maximum willingness to pay, allowing you to charge more (claim more producer surplus) while still providing consumer surplus. This is called a margin strategy. Not everyone in the segment will buy it, and not everyone outside the segment will ignore it, but having a core audience in mind informs the entire product life cycle, from design, to advertising strategy, to distribution, giving you a better shot of a solid margin without your customers feeling like they got the shaft. They got a product that was designed for them, after all.

An unfocused product might be more broadly appealing (ie, a broader swath of people might be interested), but it will be less appealing to individual market segments than products tailored to those segments. Those individual segments will have a reduced maximum willingness to pay for the product, your margins will dissolve, and your only hope to make a profit is on volume (this is called a share strategy). And if your product is targeting more markets, then it's inviting more competition, notably from products tailored to those markets. Your product will also likely be more expensive: your lack of focus means you won't be able make cost reducing trade-offs†. And your product itself will have less focus and refinement in it's design and delivery: it will be generic and will be delivered to the market in a generic fashion.

As the saying goes, you can't please everyone all the time.

Good Marketing Isn't Making Business Decisions Purely Based on Focus Groups

Focus groups are valuable data points. It's a useful exercise to actually talk to your customers and see what their needs and interests are. But that process is not a substitute for actively making a decision. Steve Jobs famously - and rather arrogantly - stated that Apple ran no focus groups before launching the iPad because "It's not the consumer's job to know what they want." What Jobs didn't say is that he had plenty of smart marketing people looking at consumer habits and identifying a need for quality tablet computer. But he was almost certainly correct in that if he had brought a bunch of consumers in a room, they would have said they wanted a faster/lighter/cheaper/better laptop or a faster/lighter/cheaper/better iPhone. It is highly unlikely that any of them would have said "I like my iPhone, but can you biggify it?"

Here's how focus groups can actually be useful:

A) Get feedback on an existing product to find areas for improvement.

...OR...

B) Put your product in front of your target market segment and to see if they actually seem to want it.

...OR...

C) Get a sense for what a target segment's unmet needs and then figure out how you can create a product that serves those needs better than the competition.

Focus groups will not drive innovation, although they can provide feedback about it. Holding focus groups will not relieve you of the need to have a forward-thinking vision if you want to make something awesome. Focus group members will not tell you the next great product you should make. How could they? You haven't made it yet and they're not fortune tellers. Trying get new product ideas by just asking people what they want is essentially asking them to do your job for you for the cost of some doughnuts and a Diet Coke. And that's just lazy.

A Note on Consumer vs. Producer Surplus

All this talk about consumer and producer surplus might trigger a sensation of skin crawling in some of you. I can understand the sentiment, but take a step back and let's talk about what those terms mean. Think of two games, one you purchased at launch for full price because you were really excited about it, and one you purchased only after the price had dropped to a level commensurate with your interest. Now, assuming that the game you purchased at launch lived up to your excitement, did you feel ripped off or gouged because you paid more money? Or did you feel like you got your money's worth and you were satisfied with your purchase?

That's what a good marketing department is supposed to provide: a good deal for everyone. The producer is able to charge a higher premium and you still feel like you got value in excess of what you paid. It's not about gouging the customer. It's about making a better deal for everyone involved. If I can make a game that gets you excited and then delivers on that promise, am I a cut-throat business man or a good developer who knows his audience? If you are willing to pay more for my game than someone else's, are you a victim or a satisfied customer?

If that didn't convince you, rip a hit off this pipe: if I can make a game so exciting that you're willing to pay full price (not buy it after a price drop, not buy it used, not rent it, not borrow it from a friend) and enough other players also feel the same way that I can make a solid profit, things like DRM, online passes and their ilk become a lot less necessary. Those ham-fisted poxes didn't emerge because companies are greedy. Some amount of shrink is expected in any industry. They emerged because companies saw a threat to profitability and lacked the marketing creativity to provide a mutually beneficial solution.

And again, let's remember: this is a business. The business needs to generate enough money in order for us to actually have professional game developers. Business is not inherently evil nor is the desire for profit. Problems develop when marketing departments (and product developers in general) get lazy and stop thinking about what products would be uniquely exciting, or how to generate better, unique value for everyone involved. Especially you.

Justin is a video game producer, consultant, and earned his MBA from Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management. He is currently laying the groundwork to start his own studio. His mission is to leverage my degree to improve the day to day experience of making games through better processes. He write about that at his full blog here: http://breakingthewheel.com

Follow him on Twitter: @justin__fischer (two underscores!)

His LinkedIn profile can be found here

*Obviously, there are other sources of crunch, managerial incompetence and decision bottlenecking being two significant ones that come to mind.

ºLooking at your customer, company, collaborators, competitors, and context is called the "5-C's Framework"; Chernov, Alexander, Strategic Marketing Management, 7th Edition (page 11)

†For more on the concept of trade-offs and efficiency, check out my other post Competitive Advantage and the Productivity Frontier, Or Why Dark Souls is the Ikea of Game Development

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like