Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How does working at a game with professional historians look like and why you should consider it too? We did it. Twice.

Making a game is a difficult process, as it involves writers, producers, designers, graphic artists, sound artists and many more. But if you’re making a historically-accurate game, you need to add another part to the equation: professional historians.

That's what we've done with Attentat 1942 and our upcoming follow-up title about post-war events in Czechoslovakia - Svoboda 1945.

When your game is about World War II era, one of the most troublesome and horrifying parts of world history, you need make sure you get everything right. How people managed to live their lives amidst historical turmoil? And how did they talk about their experiences?

And it was not only correct historical names and dates, but also the tiny details: what did the houses look like in 1939? What did people wear at the end of the war? Which kind of playing cards could you find in a pub?

This is the story about what happens when professional historians become game writers and designers.

“I am really glad to see my story reenacted by actors. Hearing my sentences and seeing it played by thousands of people,” says Jirí Hoppe from Czech Academy of Sciences, while holding a freshly-poured beer.

Hoppe is one of the historians working with us to make sure our games are as accurate as possible. So without further ado, meet our team from the Institute of Contemporary History of the Czech Academy of Sciences:

"When lead designer Vít Šisler approached us, it sounded weird. Why would I, as an academic, want to make a videogame? I didn’t play them or know them. But he talked us into it," says another historian, Jaroslav Cuhra, laughing, when we meet after the usual team meeting. "What convinced me was the opportunity to create something that could really make a significant impact among the general public.”

Initially, we had professional script writers and historians worked as advisors. But we soon found out this didn't quite work. "What the script writers wrote was too blockbuster-ish. Too much Hollywood," says Šisler. “What could maybe work in your typical World War II action game, didn't make sense in Attentat 1942 or Svoboda 1945,” he continues. We wanted to make a game that would capture the zeitgeist of that era. It was not supposed to be about spectacular heroic deeds, but about how the war changed everyday lives and split families apart.

So our historians became our writers.

It was a tough decision. “The script writers wanted us to work according to their script. But we found out it wouldn’t be accurate. We approached it from the other direction - and wrote the script strictly according to historical research. So we only used things we really know had happened,” remembers Cuhra. Historians were tasked with creating the overarching story as well as the individual characters you encounter in the games.

Marie Cerná adds: “I was honestly afraid of that. Because I felt we were constrained by the empirical materials. After all, it’s something we’ve never done before.” But their vast historical knowledge turned out to be essential in making Svoboda 1945 the way we wanted it to be. Adherence to historical facts became one of our most valuable assets. “We didn’t try to re-interpret history. We took a cautious approach. But we took care to give voice to different sides of the story,” Cerná explains.

Just how extensive was the research for our games? I asked Hoppe to recall. “Before I started writing I read around 50 books, looked into many personal stories… and it was a personal journey as well. When you delve into family histories and personal fates, you encounter things that academia usually leaves out. How did the people feel back then? We tend to read about history as just a succession of events. But how was it perceived by those who lived through them? My professional scope broadened. I saw how the war era shaped personalities, scarred families.” For Svoboda 1945, Hoppe wrote a story about a German woman returning back to the village she was born in, from where she was expelled after World War II. “I had to combine three different stories,” he says as he orders another drink.

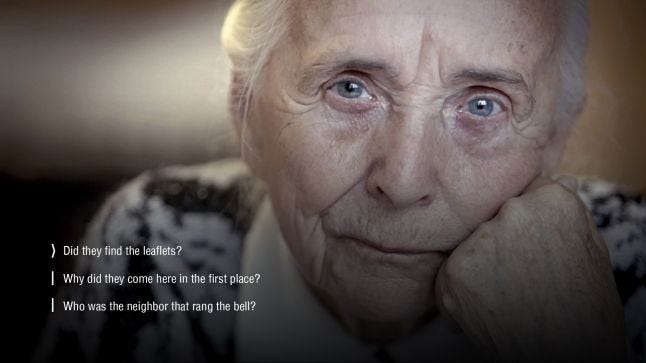

Central figure of Attentat 1942 is Ludmila, your grandmother. Her story was carefully woven from many personal accounts of Heydrich era.

Our historians are professionals, working at the top-level of an academic institution. But both Attentat 1942 and Svoboda 1942 had a surprise for them.

I asked Cerná about some unexpected obstacles. And it was the visual side of things that baffled the historians the most. “We realized we don’t know how things looked. You know what happened, but you don’t know what a room where communists made small farmers give up their lands looked like. You have concepts in mind, but not images,” says Cerná and Cuhra chips in: “Our game is very visual, featuring several finely drawn comics and a lot of interactive scenes. When we couldn’t find what something looked like, we omitted it. In a game as serious as that, we couldn't speculate.”

And there was a lot to cover. Cerná tries to remember: “We talked about party membership cards, names of streets. Could this street that this person is supposed to live on, could it exist in 1948? Or fashion, dresses. What type of helmet could the soldiers have been wearing? It was a lot of very small things and a lot of work to check everything.”

But that wasn’t all. If you’re familiar with Attentat 1942, you might have guessed that it’s not just writing. Our historians had to become game designers too.

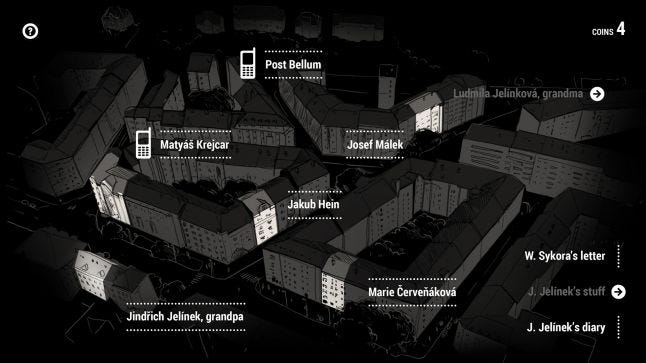

Now it’s time to talk about our game-in-the-making, Svoboda 1945. In it, you arrive in a small town in the Czech borderlands where post-war events turned many lives upside down. You have to talk to locals, investigate old buildings, rummage through long-forgotten family memorabilia. So we had to prepare the stories our historians wrote in such a way that they could form an interactive experience. We wanted to have real-life situations - be rude and you’ll be kicked out. Missed important information? Well, maybe you can ask again, but in a different way. Can’t get someone to talk? Maybe the mayor can help with that.

“Yes, that was the hardest part. Slicing the story into little blocks to create dialogues,” says Hoppe and Cuhra steps in: “It was hard to synchronize our ideas about the game. We had very long discussions to balance the gameplay, script and historical materials. It had to make sense in the big picture.”

“We made mini-games based on actual historical events. And they had to be connected with a story. My character is a local chronicleman. Obsessed with history. A sympathetic weirdo, who keeps a collection of old photos you can visit in the game,” describes Cerná her work.

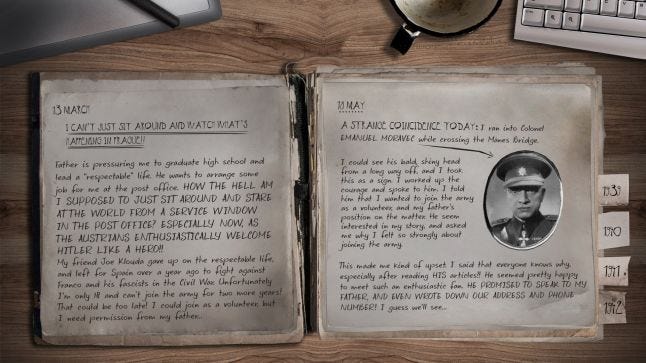

There's a number of memorabilia and historical artifacts to sift through. For example, this is your grandfather's diary, where he mentions for example former famous Czechoslovak Colonel Emanuel Moravec, who later became minister in the protectorate government.

There's a number of memorabilia and historical artifacts to sift through. For example, this is your grandfather's diary, where he mentions for example former famous Czechoslovak Colonel Emanuel Moravec, who later became minister in the protectorate government.

How do they feel now about their brief visit into game development? “It was crazy! But in an interesting way. It’s been a ride into a totally different world,” recounts Cerná, who even visited Independent Game Festival in San Francisco where we were nominated for Excellence in Narrative with Attentat 1942. “You can’t take away your profession. So we’re glad Vít managed to keep it together ,” she says, looking at the lead game designer Šisler. He adds: “We had to do a lot of project management, think about how to keep everyone informed about where the story was going. I also helped to polish the characters. But it was always a dialogue. We had to synchronize our expectations for the project.”

And we’re immensely happy it worked out. Without Hoppe, Cerná, Cuhra and Kokoška, Attentat 1942 or Svoboda 1945 would have never happened. Having professional historians on board was essential for making our games the way we wanted - as truthful, vivid, unsettling interactive depictions of an era, that resonates even today. So, allow me to be a little sentimental: thank you so much. It’s because of you that our games have a unique atmosphere, one informed by deep knowledge of past horrors and the minutiae of everyday life. We couldn’t do it without you.

It is only thanks to punctual work of our historians that we could create this many distinctive characters with interconnected fates.

Thus, the conclusion: When putting your dev team together, include people who are not gamers, who don’t have deeply-rooted ideas about what a game should be like or how videogame storytelling works. Reach outside of the game community, talk to people from different disciplines, get them on board. They have different perspective than those immersed in the videogame world. Your game can only benefit from that.

Honestly, it’s been a journey for all parties involved. And that includes our players, who will be soon able to double-click the icon of Svoboda 1945 and immerse themselves in the events that shaped central Europe. While listening to stories that echo the real memories and tragedies.

Wishlist Svoboda 1945 here and visit our homepage at charlesgames.net and read more about our projects

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like