Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Why publishers leave Steam? A make-your-own-platform trend? Global PC publishing, contemporary pricing, looking for the new audience.Let`s discuss the current problems and trends in the PC game market and try to find answers together?

Whenever I bring up big questions about the future of the games industry I can’t help but feel like the village idiot. But I guess Thursday evening is as good a time as any to discuss the current problems and trends in the PC game market. Let’s use our imagination. What could be changed?

Sorry about all the GIFs in in this article—hopefully they’ll help me lighten the mood a little.

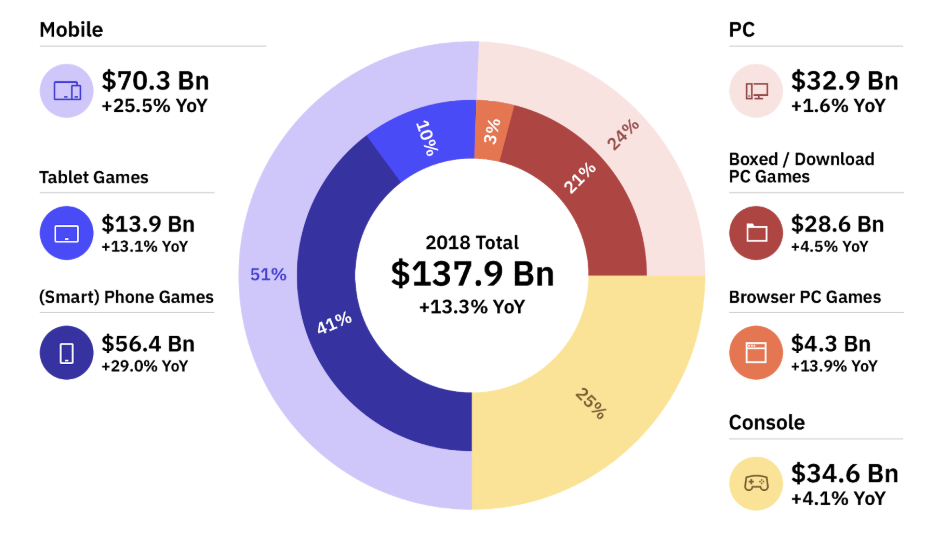

So what does the pie look like? According to UBM (the host of GDC), PC is still the most popular platform among game developers. 60% of them are currently making games for PC and plan to continue working in this market segment. PC games also account for nearly a quarter of the global video game market ($33 billion a year). Based on predictions, revenue from PC game sales will grow by more than a billion dollars over the next two years. By 2021 the PC game market will be growing by an average of 4.2% per year.

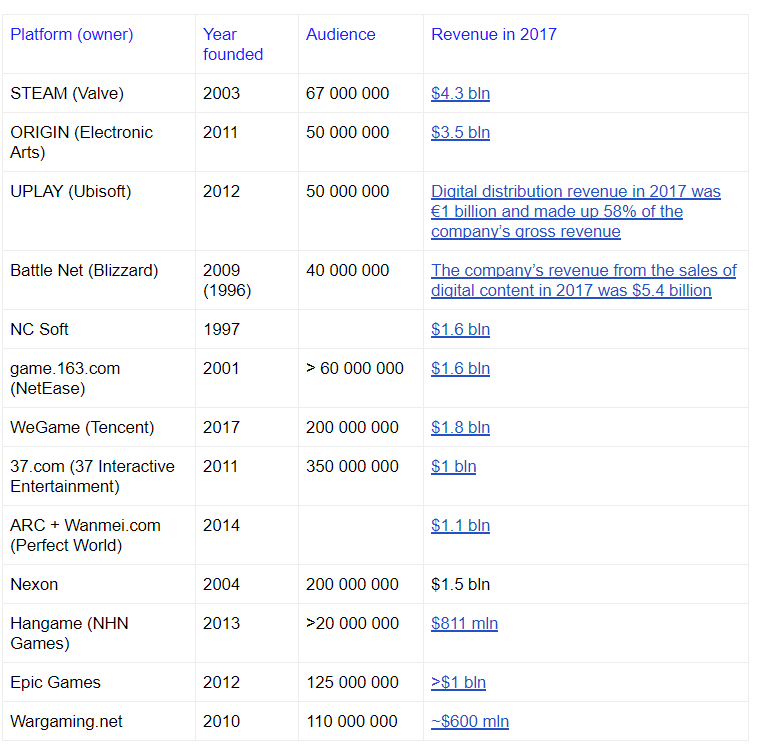

In other words, this piece of the pie is big, and it’s getting bigger fast. Our “pie” is made up of a few large “islands,” digital distribution platforms created by game developers and publishers. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting ones.

And here’s a more detailed list of digital distribution platforms. The list contains just under 200 platforms and storefronts from around the world. Please help us expand it.

I think it’s safe to say that by now we’ve all realized just how big the pie actually is. It’s time to take a closer look at the filling.

It looks like we’re barreling headlong towards a major decentralization event. Several new platforms will appear over the course of 2019, each with its own customer base. And at least some of them will have an opportunity to change the market drastically. This is just a taste of what we can look forward to next year:

· EPIC Games has more than 100 million Fortnite users to serve as the audience for its platform.

· Discord has 130 million users and its own storefront (and a platform is in the works).

· Bethesda is going to launch Fallout 76 on its own platform (rumor has it we’ll get access to third-party games later on).

· Ubisoft’s Uplay service is gradually making it easier to release third-party games on the platform.

· Tencent’s WeGame platform is itching to break into Western markets in 2019.

· The same goes for Kongregate’s Kartridge platform, which is coming by the end of 2018.

· A number of blockchain-based platforms are also on the horizon, including Robot Cache from Brian Fargo (InExile) and Shark from Fig.co.

All false modesty aside, having an audience and the ability to freely interact with it are the most valuable resources for both platforms and developers. After all, Steam essentially sells a developer’s audience back to it, and it does this despite offering meager analytics and no options for tracking marketing campaigns. However, this approach is typical not only for Steam, but also for all major players in the third-party distribution market.

If you bring your audience to someone else’s platform, you have no guaranteed way to interact with it. Just think for a second: how many indie devs with popular games have managed to effectively transfer their audience to a sequel?

Good companies should be able to calculate their own profits, and “what am I giving up 30% for?” is a pretty practical question to ask when it comes to medium-term planning. However, it’s not like every developer with a successful game can just go ahead and create its own platform. Even if you release a BB or AAA game every year that attracts hundreds of thousands of players, launching your own platform won’t exactly be a utopia. Good games from other devs will only keep an audience on your platform until your next title comes out.

The mantra “we’ll release the game in Asia—the audience there is huge!” isn’t the most helpful thing in the world. European publishers and developers of all sizes have just as much trouble launching in Asia as their Asian counterparts do in North America or Europe.

Not only do you need high-quality translation and localization, you also need to have an understanding of the unique characteristics and mentality of the players in that region, to say nothing of purely utilitarian concerns such as finding regional platforms and negotiating contracts.

You need to develop an optimal traffic strategy and conduct a high-quality PR campaign in every single region in order to create a core audience. You have to know which platforms to use to communicate with your audience and be able to do it in Asian languages.

If you’re not a major publisher, refusing to use local distributors (which charge a 5% –30% commission) will require a pile of contracts and related activities: royalty statements, reconciliations, document workflow, the whole bit.

The good old “big box” days, when shipping, retailer margins, and physical media manufacturing costs gave us the $60 standard for the US market, are long gone.

In the era of digital distribution, dominance pricing is easier, with prices in each country based on the stable currency’s exchange rate to the local currency adjusted for purchasing power.

None of the existing conversion systems apply fine adjustment to regional pricing. Nobody knows how to choose the ideal equivalent price for a $15 game in Japan, Mexico, China, Poland, Russia, England, and so on. Everyone just takes the ratio of sales to price for a group of similar games and stops there. What should the price really be to ensure the largest number of sales and optimal conversion into purchases for each region?

It can take anywhere from one to several months for a developer to get their money after a copy of their game is sold.

There’s no way to quickly reinvest the profits from a game or in-game items directly into advertising, which is especially painful for smaller teams and games.

Integrating payment aggregators is often unprofitable. Payment processing intermediaries that handle bank cards usually charge a commission of 5%—6%.

Games that don’t require a constant connection to a server suffer from piracy. There are several stolen copies of a game for every legal copy sold. Popular online games tend to attract large numbers of cheaters and communities that make money illegally by exploiting vulnerabilities in the game’s software. Third-party copy protection solutions like Denuvo don’t last long and are expensive.

We hear a lot of magic formulas in favor of piracy: “if the game is good, I’ll buy it later.” And there’s the old chestnut: “I always download a pirated version for a test run. If I the game, I’ll buy it.” But neither of these excuses reflects the whole truth.

While active players prepare for the special kind of hell that awaits them (imagine trying to wrangle a dozen different platforms, each with its own launcher), the platforms themselves are fighting for immersion.

Let’s call a spade a spade: most of the major players don’t buy traffic. They mainly work on brand awareness, not direct sales—even with an audience of millions. The second pillar is retention. Any decent platform will use your games and the traffic you drive to them for that.

A thousand hits cost three dollars. Buying this kind of traffic is more cost-effective—the more data you have, the better you can evaluate its quality.

It would seem like the next logical step for participants in any market would be to start exchanging user data. This year advertisers have been actively discussing the CDP (Customer Data Platform, a subspecies of DMP) and the holy grail of a 360 degree profile. They’re talking about optimizing traffic and proper audience management, and they actively use and buy segments or raw DMP data from each other. So why is PC distribution so far behind in this respect? I honestly have no idea.

Do you want to create advertising that only targets paying users or PC gamers who play only specific genres? Well, there’s currently no way to do this without access to third-party data. There’s also no way to exclude players who have already purchased your game on another platform and won’t want to buy it again.

Not only do companies not share data to optimize sales, they’re often reluctant to even talk about it.

So we’ve mused for a bit and realized that the games market is big and getting bigger. A lot of people want in. However:

· Everything is centralized around the big “islands.”

· Those few companies that aren’t centralizing are hastily cobbling together their own platforms.

· Comprehensive global publishing isn’t really a thing yet—it still takes truckloads of labor for every single territory.

· In other words, there’s no magic “Publish to the World” button.

· Trying to set effective prices in different regions is like some kind of voodoo dance with drums and ancient incantations.

· Your money is going to take a long time to get to you.

· Piracy and cheating continue to be the bane of the industry.

· Your audience, data about it, and access to it are the three golden keys to the gates of paradise in this brave new world.

Many of my colleagues in the industry are skeptical about current trends. “Show us where the traffic is, and we’ll go there,” they say. “Nothing else matters.”

I’m certain that if the games market is about to become overcrowded with new platforms, people need to start thinking about consolidation. They need to learn not only to exchange data, but also to create their own tools for gathering and analyzing data (unfortunately, all open-source solutions in this market are pretty crummy). Someone is eventually going to create that “Publish to the World” button, then sell it for a fortune. Before this happens we need to reduce costs and make the ubiquitous sales and discounts irrelevant by actually lowering the prices of games.

Which problems do you see for the PC game distribution market? Not to be overdramatic, but what can we do to change the world for the better? What’s your vision of an ideal world? Or maybe you think we already live in an ideal world and shouldn’t change anything. Good enough is good enough, right?

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like