Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Japanese developers, and the organizations supporting them, on Japan's slow but growing indie scene.

March 2023 will mark ten years since the launch of BitSummit in Kyoto, an event created with the goal of introducing games from Japanese independent developers to the rest of the world. It also perhaps marks the moment that indie games first really started to gain recognition in Japan, following the indie revolution that swept the game industry in the West after the rise of Steam, the Xbox Live Arcade era, and other forms of digital distribution.

Although the indie scene has been integral to the rise of the global industry, with innovative titles like What Remains of Edith Finch, Vampire Survivors, Her Story, Celeste and so many others becoming critical and commercial success stories—often with the support of crowdfunding and boutique indie publishers—why have we not seen indies have the same impact in Japan?

The answer to that question would perhaps depend on your definition of "indie," which is a term that has become rather amorphous in the West.

It's not that there aren't Japanese developers shunning the big-budget publisher model to carve their own path. There have been instances of successful solo projects making waves long before the West’s indie boom, such as Touhou Project, a bullet hell shooter that has spawned multiple games and multimedia spin-offs. Cave Story also remains influential as a Metroidvania. These are, however, examples of projects made in their creators' free time.

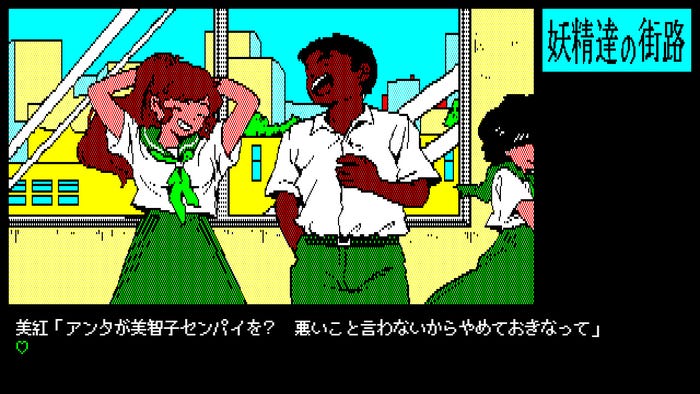

In Japan, such projects are referred to as "doujin soft." That is, games created by hobbyists for fun rather than profit. The term "doujin" literally translates as "same person" but can be taken to mean independent self-published works, which can apply to anything from manga to novels to music. Games have naturally been part of this as early as the 1980s during the rise of the PC, especially with NEC’s popular 8-bit PC-8801 (or PC-88 for short), which was capable of producing detailed pixel art.

"I started making games in my teenage years," says indie developer Giichi Totsuka, whose upcoming visual novel game Retro Game Aliens takes the PC-88's aesthetic as inspiration. "There were magazines that would hold contests for you to submit your own games, so I would apply to those competitions."

Retro Game Aliens will be released on Steam

Retro Game Aliens will be the first title Totsuka has published on Steam as a commercial release. Before now, as well as entering magazine competitions, Totsuka would make other visual novels on free engines that had a website allowing creators to promote their work. That's because—unless devs in Japan are also making their own websites to advertise—there simply isn't an infrastructure in place that lets them share their games with a larger audience.

For doujin communities, there is Comiket, a comic market held bi-annually in Tokyo, where hundreds of thousands attend to buy and sell doujin works. Again, most of the works are not usually sold for huge profit. Alvin Phu, CEO of doujin game publisher Hanaji Games explains, "outside of Comiket, there isn't a strong community or place for people to come together to talk to each other about what they do."

As well as making games in his own time, Totsuka also works as a game reporter, and it was during a trip to Tokyo Game Show—specifically the 2013 edition when organizers first introduced an indie booth—that he became inspired to start exhibiting his own projects at the event. "You used to see more doujin groups making their own games in a close and isolated community," he says. "But in recent years, there are more [people asking] 'have you found a publisher?' So it's becoming more commercial, and publishers are stepping in to see which games are viable to be published."

"In my opinion, 'indie' was imported from overseas to Japan," says Back in 1995 developer and Indie Game Survival Guide author Takaaki Ichijo, who highlights a cultural as well as monetary difference between doujin and indie, where the mindset of the latter might seem no different than a salaried position at a big company, but without long-term stability. But if indies are a foreign import, then they also require the same infrastructure, resources, and support in order to grow, which organizations both native and expat have been establishing.

One example would be an incubator or accelerator program, and as luck would have it publisher Marvelous recently launched Indie Game Incubator (IGI)—the first of its kind in Japan—back in 2021. Ichijo helped co-found the incubator, and is currently overseeing indie developer relations. It was the existence of that program that allowed Nao Shibata to make his debut indie game, Ninja or Die.

Nao Shibata's debut indie release Ninja or Die

A former veteran at Natsume-Atari, Shibata started as an art designer but had been used to wearing multiple hats at the company, including director for its mobile titles. "I was feeling like I was running a company within the company, so I was confident that with my background I could become a solo developer," he says. "Then when I started my own company, I realized that I didn't know enough, so that's why I joined the incubator."

While Marvelous gets something out of the program by securing titles they add to their release roster, such as Ninja or Die, program manager Matias Kaala says this is ultimately charity for the company.

"Usually with programs where they help you and give you money, they have IP rights or something else in return, but we connect developers to a network of over 80 publishers after the program, and all we ask is that they tell us if they are getting an offer, and then we decide if we want to make a counter-offer," explains Kaala. "But in the end, the developer has the freedom to choose who they want to work with."

Shibata, Ichijo, and Totsuka were part of the games industry for many years before going indie, with indie development seen as less of a viable career path for those just getting started. By comparison, ElecHead developer and IGI mentor Nama Takahashi is something of an exception, having made his puzzle-platforming hit while still studying at a specialist game design school. "In school, teachers ask you to go to bigger companies, but I realized there was an indie scene, so maybe if I could do everything then I could try the indie route," he says. Although modest when speaking about his career plans, he already made enough profit from ElecHead to invest in another indie project.

There are success stories, then. But there's a sense that in order for the Japanese indie scene to continue growing, work must be done to establish a visible community. That was the main reason Phu wanted to establish Tokyo Indies, which hosts monthly meet-ups for developers or anyone interested in being part of the industry.

Growing up in the United States, he was part of the Boston indie game dev scene and would go to monthly meet-ups while in college. "We would meet up at a bar, bring our builds, do these small presentations, and now they have it at MIT as well in a classroom," he explains, adding that he wanted to help establish something similar in Japan. "We were getting about 70 to 80 people every month," he says. "During COVID we were doing online streams, but when we started holding it in-person again, over 130 people showed up! Everyone missed this!"

Tokyo Indies in full swing

Just as doujin creators are often isolated within their own circles of interests, Phu acknowledges the indie community can also be quite fragmented. For instance, there might be divisions between people using Unity or those using Unreal, as well as anybody who still just considers themselves doujin.

Asobu is an attempt to bridge that gap and unite everyone under one roof. Describing itself as a 'lighthouse' for indie creators in Japan, Asobu is a physical hub in Tokyo funded by sponsors, which members can use as a working space, hold presentations and workshops, and even conduct play tests. Since its founding in late 2019 however, the pandemic has put much of its plans on hold—although the hope is for a reopening later in 2023.

Right now, access to the hub is still limited to Asobu's early members, including Takahashi who says it was a good environment for promoting ElecHead. Although he self-published the game, he also wanted it to reach an international audience. Asobu's resources and expertise were therefore instrumental in its release, and he credits the organization's co-founder and former community manager Anne Ferrero with the game's translation and trailer. Notably, Takahashi's itch profile, where ElecHead was first shared as a demo, is also in English.

Ensuring a game can reach a global (read: English-speaking) audience is vital to the success and visibility of Japanese indies. It's one of the biggest obstacles for Japanese, as well as other non-English speaking, developers who aren't able to fluently communicate in English. For instance, Totsuka tells us publisher Waku Waku Games decided it would be more profitable to localize Retro Game Aliens in English and Chinese to attract a larger audience in lucrative markets. Bridging the language gap doesn't simply mean prioritizing game localization, though, as there are other linguistic barriers that might prevent devs from even starting a project.

Kickstarters, for instance, rely on international backers. That means it's almost essential to have an English-speaking team run the campaign. If a developer wants their game featured on an international showcase like Day of the Devs or Steam Next Fest, it will often require them to submit English documentation (Asobu incidentally also hosts its own regular online showcases). There are also many helpful online resources used by indie developers that haven't been translated to Japanese. Even the communities that Japanese indie developers belong to can be fragmented based on language.

"BitSummit has a Discord server, and it's always the English people speaking," says Shibata. "It's probably a cultural thing where we feel like we don't want to intrude on a conversation or start a new topic, especially when there's different languages you might not understand."

That's one area IGI has focused on getting right. The program has overseas mentors giving lectures, but provides interpretation for people who need it. The program is also restricted to people living in Japan who speak Japanese. "What we're really trying to do is empower local indie developers," says Kaala. "I don't want to say we dismiss expats, but I feel like the local scene is in so much more need of help."

What's more surprising is that, given Japan's reputation as the spiritual home of video games, there's virtually no support from the government for developers in the form of grants, sponsorships, or tax relief. That, though, could soon change. Having held talks with officials about the IGI, Kaala is cautiously optimistic that those in power are slowly but surely waking up to the industry's potential, pointing to the first ever Japan Pavilion at last year's Gamescom, which featured a delegation of Japanese indie developers and their games.

The Japan Pavilion at Gamescom 2022

That kind of international outreach and cultural exchange where Japanese indie developers can have a platform is something everyone would like to see more of. Takahashi hopes to be able to submit a future game for award consideration like the IGF or attend PAX, explaining that he really looks up to these international shows. Because if Japanese indies aren't getting the spotlight, then Western developers influenced by Japanese culture and aesthetics are, be it the Kurosawa-inspired Trek To Yomi or countless retro pixel-art titles.

For Japanese players discovering indie titles, the origins are also becoming blurred as more Western publishers have gotten savvy with localizing their games into Japanese. "Anybody that is an indie dev emulates the Japanese '90s style of pixel art, but when Japanese indie games make the same thing, our games are not easy to find," Ichijo wryly observes.

That notion that Western indie publishers with more resources can easily beat Japanese indies at their own game uncomfortably recalls the infamous GDC panel where Fez creator Phil Fish, whose own game drew inspiration from classic Nintendo games, told Japanese developer Makoto Goto that Japanese games "just suck".

"What's funny is that's how I moved here and got my job here, because on my first trip to Japan, I messaged [Goto] on LinkedIn saying, 'I heard what happened' and that I wanted to work as a programmer in Japan, so he invited me for drinks, which was how I was introduced to my old boss," Phu says. "So if Phil Fish hadn't made that comment, Tokyo Indies wouldn't be here right now!"

Thanks to Cheryl Ng at Asobu and Matias Kaala at Indie Game Incubator / Marvelous for translations.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like