Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Tatiana Vilela dos Santos is an indie game designer & interactive artist making games with special interfaces. She gave in March 2018 a 60 minutes talk at the GDC titled Game Design Beyond Screens & Joysticks. This article discusses details of this talk.

Tatiana Vilela dos Santos is an indie game designer and interactive artist. She makes games with alternative controllers and render interfaces, all part of her interactive multimedia project MechBird. In March 2018, she gave a 60 minutes long talk at the GDC titled Game Design Beyond Screens & Joysticks about tools she uses to analyze and design this specific kind of games. This article discusses details of this talk.

As we saw in the previous article, physical interfaces can be used as part of a gameplay by constraining body movements. But the whole physical environment can also shape players’ state of mind and be used to provide specific kind of game experiences. Of course, the context of play has a strong influence on players’ experience, especially in exhibits and showcases. When I designed Virtual T-Break, I had to include in my reflections that the game would be played in a VIP lounge. This meant that most players would be in a professional environment wearing suit & tie. Making them jump like monkeys in front of a Kinect wasn't an option.

As a game involving players physically and my most exhibited game so far, Adsono allowed me to witness lots of different players’ reaction based on the context of play. The most striking differences are between game related events and clubs. While in game shows players are sometimes reluctant to make a spectacle of themselves, clubs provide a more favorable climate to playfulness. Clubbers are usually less inhibited not only thanks to intoxication but also because they came to dance in the first place. But as designers, we don’t have to passively suffer the effects of the context and adapt to it. We can deliberately foster a climate conducive to the experience we want to provide based on how the digital part of the experience is integrated to “reality”.

Shaping players’ behavior through scenography

In 2017, I made my first solo exhibit: IN.PLAY//OUT.PLAY. I wanted to take this opportunity to experiment with the influence of scenography on players' behavior. So I designed Dead Pixels²: an alternative version of Dead Pixels played with twin-stick gamepads and projected on a real canvas put on an easel. I wanted players to focus more on the graphic composition emerging from their game and less on the physical space. Not only to highlight playing as a creative act but also to see if that setup would somehow change players’ behavior.

![]()

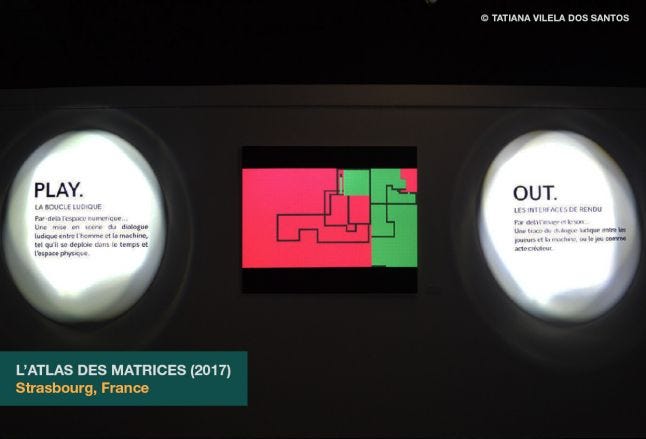

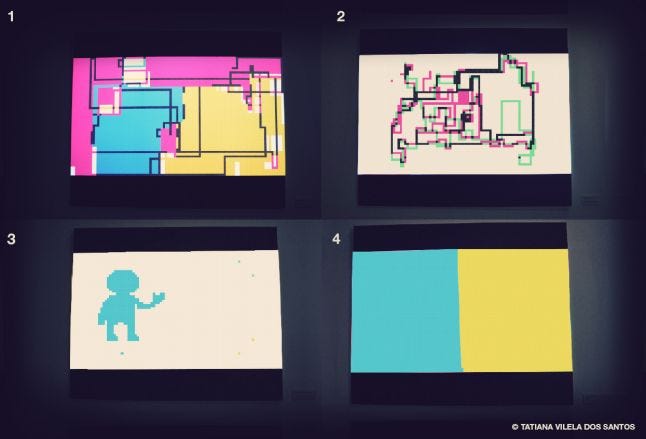

In addition to the scenography of Dead Pixels², I made another installation to spotlight the graphic composition emerging from the players’ game: L’Atlas des matrices. Always exhibited alongside Dead Pixels², L’Atlas des matrices is a projection on a canvas fixed on wall placed beside the easel. It displays screenshots of all Dead Pixels²’s endgames. As a collection of maps, the slideshow allows visitors to retrace each game and observe its claimed and disputed territories. The scenography of L’Atlas des matrices is purposely designed to look like a standard gallery setup. The canvas is hung on a white wall. A white label at the bottom-right of it gives information about the work including its year of creation and the techniques used for its making, directly copying the format of paintings labels. The point was to impel players to be creative in their play and generate new endgame screenshots never seen before.

Indeed, these incentives to be creative worked very well. Not only the games became more diverse but players even started to go beyond the game rules and directly draw with their gamepads. This behavior never emerged from the original version of the game: Dead Pixels. The scenography incentives overshadowed the game system ones. Players didn't follow the rules of the game anymore, the announced goal in the title screen, but rather experienced the installation as a creative toy and its gallery. These players were well aware that their graphic work would be displayed until the end of the exhibit and likely seen by other visitors. Their play experience wasn’t happening in the digital game inside the frame anymore but outside of the screen, in the physical space they shared with the other visitors: the art venue. The border between the digital game and the physical gallery was blurred by video projecting on material canvas.

Shifting from digital to physical game

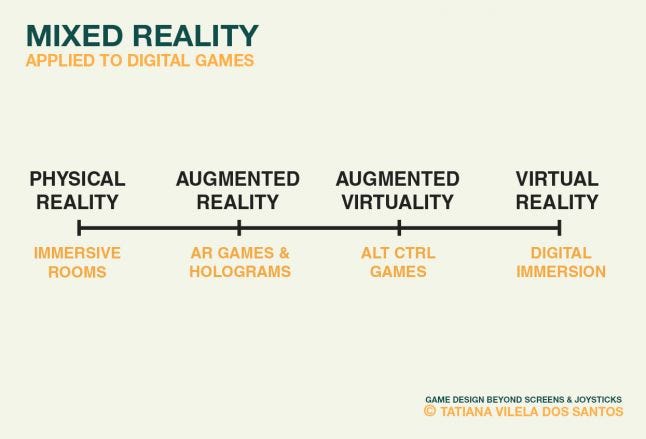

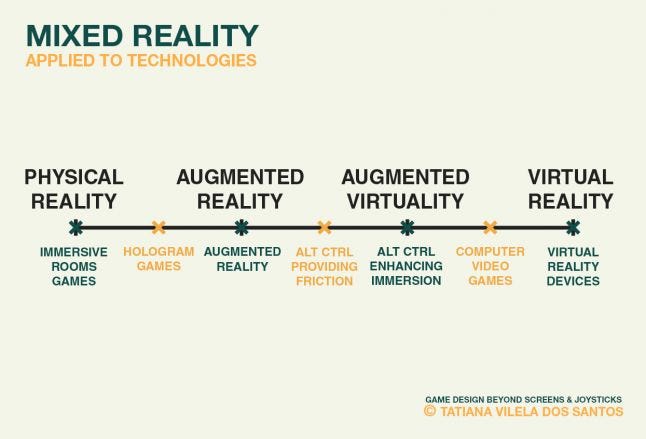

Once emancipated from common interfaces, game designers can freely choose where they want their players to project themselves. Does the game experience aim to immerse players in a digital environment or is it meant to invade the physical world with some digital magic? The mixed reality taxonomy is an interesting lens to analyze game location: where the game is actually happening. Developed by Milgram and Kishino in the early 90s to analyze display technologies, I think it’s also relevant when studying digital games. They famously developed a reality–virtuality continuum, an axis featuring two limits. On the right, there’s the virtual reality. On the left, we find the physical reality. The segment passes through two points: the augmented virtuality and the augmented reality.

According to my reading of the Reality-Virtuality continuum applied to video games, I’d place on the extreme right any game using a cutting edge technology regarding digital immersion, currently: VR devices like HTC Vive and Oculus Rift. Slightly on its left, I’d place standard video games projecting their players in the virtual world behind the screen. Then, on the augmented virtuality point, I’d place alternative controllers made to enhance immersion. A prime example of this could be Guitar Hero. Between augmented virtuality and reality, I’d place alternative controllers providing friction, like Dead Pixels or Snailed It mentioned in the second article. On the augmented reality point I’d place AR games and/or based on GPS navigation: the physical world is displayed on a screen with some digital addition to it. The most famous example is probably Pokemon GO. Between AR and the physical reality I’d place holograms: the digital invades reality but the borders between the two worlds are still very defined. And finally, on the extreme left, I’d place games as immersive rooms like laser tags and escape games using digital technologies fully blended to the physical world.

This last case is the most interesting for me. The more the game is integrated to reality, the more the player's committed to the experience. When a game is integrated to the physical world, player's focus is not divided between two realities competing with each other anymore. At least way less than when the border between the digital and physical worlds is well defined. This is something that particularly stroke me in a game I made 3 years ago, jungle.in. jungle.in is a cooperative puzzle game in an immersive room for as many players that can fit the place. The room is a cube of 30 meters squared (about 320 feet squared), invaded with lianas of 1900 LED. These lights lianas are animated. Each liana starts with a female plug and ends with a male one. Some lianas are plugged together, some are not. The color and rhythm of the animations follow hidden rules that the players have to understand. Players’ goal is to rewire the giant electrical circuit surrounding them to sync all the lights animation. In jungle.in, players are not communicating with or through a machine. They’re inside the machine. They’re not projected in a digital world but instead are all together inside a magical room trying to figure out what are the laws ruling this unique space. When they’re playing in an immersive room, players are physically involved in the experience. Physical immersive environments provide a unique sense of presence with which a digital space can not compete.

Shifting from fictional to abstract game

Lots of my games are not only taking place in the physical world but also don’t skin the interactions with a fictional representation : pressing the A button won’t make a fictional avatar jump. Below is a double-axis diagram I made. The reality-virtuality continuum is on the abscissa while, on the ordinate, there’s the level of fiction skinning the game. In other words, this double-axis shows how much the experience feels like being part of the “reality” as opposed to fictional world both in terms of storytelling and technology. On the bottom right are the most fictional games. There, I’d put standard role-playing video games for example. On the top-right part there are games using technologies that project the player into a digital environment but without storytelling, like old arcade classics. On the bottom-left part, there are games with a narrative background but taking place in the physical world like Live Action Role Playing games and escape games. Finally, on top-left part, there are games taking place in the physical world without narrative background like Laser tag and sports games. .jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Below is the double-axis with actual games. Some are digital, some are not, some are well-known classics and some are games of mine I already talked about. Here is how I’d classify them:

Bioshock: Players embody fictional characters with narrative background and the game is staged in the digital world.

Guitar Hero: Players don’t embody fictional characters but use an alternative controller contributing in the illusion of playing guitar and the game is staged in the digital world.

Pokemon GO: Players embody fictional characters without a narrative background and the game is staged partly in the physical world and partly in the digital world

Masquerades & Massacres: Players embody fictional characters with narrative backgrounds and the game is staged in the physical world.

Asteroids: Players embody fictional characters without a narrative background and the game is staged in the digital world.

Pong: Players don’t embody fictional characters and the game is staged in the digital world.

BLACKBOX: Players don’t embody fictional characters but use an alternative controller contributing in the illusion of beating the rhythm and the game is staged in the digital world.

GPU: Players don’t embody fictional characters and the game is staged partly in the physical world and partly in the digital world.

Adsono: Players don’t embody fictional characters and the game is staged in the physical world.

Judo: Players don’t embody fictional characters and the game is staged in the physical world.

Pro Wrestling: Players embody fictional characters without a narrative background and the game is staged in the physical world..jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

When players are not embodying any fictional character in a digital world but instead play as themselves in the physical world, their bodies are fully committed to the experience. Not only because the game is directly requiring them to move, but also because the lack of narrative reduces the cognitive load necessary to play. This can be used to better take control of their body and focus on what they’re physically doing at the moment. This focus on the physical part of the experience can trigger unique social experience in multiplayer game. This is the kind of experience I aimed with å¯ã‚²ãƒ¼ãƒ (pronounced “negaemu”). å¯ã‚²ãƒ¼ãƒ is a competitive wrestling game for two players based on an alternative environment: a mat covered by a video projection and featuring three boxes with two arcade buttons: a red one and a blue one. The projection also features a red and a blue snakes swallowing each other’s tail. At each round, the system randomly highlights a block of two buttons. When a player presses its highlighted button, his snake eats a bite of the other’s tail. Players’ goal is to eat their opponent’s snake whole. å¯ã‚²ãƒ¼ãƒ requires players to stay aware of their body, their partner’s one and their environment. The game is designed to trigger playfulness into the players. This is what we’ll address in the next and final article.

In the next article

In the next and final article, I’ll conclude by addressing the personal reasons that led me to embrace this specific kind of game design. What motivates my choice, as a game designer and digital artist, to design physical-abstract games? How can this kind of games trigger playfulness and unique social encounters?

→ Go to part 5/5 : Conclusion

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like